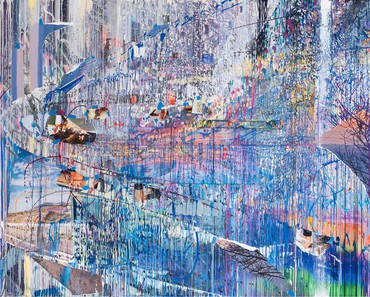

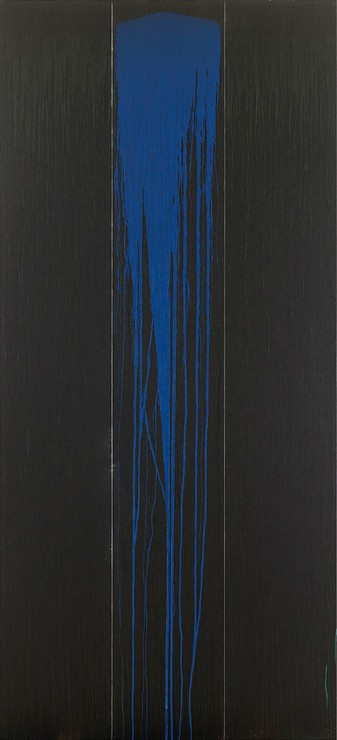

With a storied career spanning more than five decades, Pat Steir is a trailblazing presence in contemporary painting. She was one of the relatively few women who came to prominence in the New York art scene of the 1970s, initially pairing iconic images and texts to interrogate the nature of representation. In the mid-1980s, inspired by East Asian art and philosophy, she adopted a looser, more performative approach to painting. Harnessing the forces of gravity and gesture, she developed techniques of pouring, splashing, and brushing thinned paint onto canvas, often working at a monumental scale.

Sarah Sze’s art utilizes genres as generative frameworks, uniting intricate networks of objects and images across multiple dimensions in sculpture, painting, drawing, printmaking, and video installation. Her works prompt microscopic observation while evoking a macroscopic perspective on the infinite.

Sarah SzePat, when I think about your work, my mind goes to Fan Kuan’s Travelers among Mountains and Streams [late tenth–early eleventh century], one of my all-time favorite paintings. Were works such as this important for your own work in any way?

Pat SteirIt’s a long journey! In 1978, I started a painting called The Brueghel Series (A Vanitas of Style). I took a vanitas flower painting from Brueghel and divided it into eighty-four sections. In each section, I utilized the style of a different artist. I addressed each work of art as a separate thought, and I painted each of the panels in the style of one of eighty-four artists. Through that, I discovered japonisme, and through japonisme, I got to Chinese painting. One thought led me to the next.

SSI grew up with my great-aunt Mai-mai Sze’s translation of the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting [1679–1701], a classic guide to Chinese landscape painting, which I believe you read. Does the practice detailed in that book—for example, painting a certain rock over and over again or making a chrysanthemum with an exact brushstroke—have a relationship to your work?

PSWell, I got there a few ways. John Cage’s thinking, his system for making chaos, was a major influence on me: chance, meditation, and studying, if not the actual works, then reproductions of the works. And more than that, studying the philosophy that brought artists to their images.

SSAfter doing that, did you create a philosophy that brings you to your own images?

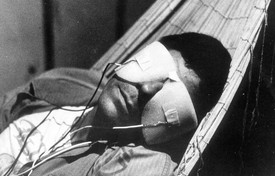

PSThat doesn’t have much to do with me, but it’s a good idea [laughs]. When I’m working, I actually don’t think about anything. Cage said, “When you start working, everybody is in your studio—the past, your friends, enemies, the art world, and above all, your own ideas—all are there. But as you continue painting, they start leaving one by one, and you are left completely alone. Then, if you’re lucky, even you leave.” So I don’t speak much about my work because there’s nothing to say. I make the work. I’m very influenced by the idea of chance, of accident, by the process of observing nature and by observing nature through art, and then letting my more or less random process make the thing itself. I try to make paintings without talking too much about them. They’re not abstract and they’re not theater. I think of them as both a picture of a waterfall and the waterfall itself because what the viewer sees is what gravity makes, what the weight of the paint makes, on the canvas itself. I like very much that the paintings make themselves.

SSWork makes work. I think of the letter Martha Graham wrote to Agnes de Mille about how instead of satisfaction artists are left only with “divine dissatisfaction.” It’s all about that moment when you come into the studio and find that the materials are the ones telling you what to do.

PSSometimes I work and then I come back the next day and marvel at what the paint did. The paint does its work during the night: the weight of the paint and the air in the room make the painting happen.

SSBut we know that the painting doesn’t always happen in the night, and that sometimes the next morning is very bleak. It seems like there’s a ritual you have to create that air in the room. Do you ever practice an emptying-out in the same way one might draw a rock over and over and over again?

PSYes, repetition is the main point here. When I started painting, I thought of painting as a research project, and I was looking for something that I could find in myself but that was more than me. So I started with research: first with small images on a big canvas and then with an image of a rose crossed out in the background, thinking that would make a white painting or a black painting if the image was there but crossed out thoroughly enough. So I worked very slowly up to what I’m doing now—for more than fifty years. When I got to where I am now, where the painting makes itself, I thought it was more than me because the painting wandered away: it spoke for itself. I didn’t want to express myself, which is what makes it different from poetry as a form of expression. I mean, of course there’s abstract poetry, but my favorites are [Rainer Maria] Rilke and [Constantine P.] Cavafy. They tell you something. Cavafy clearly tells you about his past and his thoughts about where he is from the past, and Rilke tells you the same in a different way. But I didn’t want to say anything [laughs]. So it took me all these years to get to say nothing. It’s like getting knock-knock jokes [laughs].

SSOne of my favorite poems is kind of like a knock-knock joke and a love letter to painting all in one: Frank O’Hara’s “Why I Am Not a Painter.” Emily Dickinson will always be my touchstone. I’m drawn to her economy of words and space and, conversely, her immense scale of thought. You have a close relationship with Anne Waldman.

PSAnne is one of my closest friends and collaborators. We’ve worked together many times over the years. I’m close to and admire so many poets—Mei-mei Berssenbrugge is another. The American poets of the 1950s are among my favorites, as well as English Romantic poetry. I love reading poetry.

SSCan you talk about whether and how nature has impacted your work, given that you had a second studio in Vermont and now you have one on Long Island, overlooking the sea? Is there a difference between working in nature and working in your Chelsea studio, with its view of the Hudson River?

PSWorking in nature is relatively new to me. Before that, I always felt that I had to work in a city, in a place with no nature, that I couldn’t make paintings that imitated nature in nature because I’d always be outdone by nature. I’d have a sense of failure because nature itself is so breathtaking. But about fifteen years ago, I overcame that feeling in Vermont. When I was there, I would sit and sketch in the air the birch trees in the snow, all black and white. Winter paintings.

SSI remember talking to you at the beginning of the pandemic, when you isolated in the country. I asked you how you were doing and if you were making work, and you said, “I’m a runner, so I have to run.” You told me you missed the studio. I was living right next to my paintings. I’d literally wake up in the middle of the night, get up, do a few things on a painting, and go back to sleep. I loved living in my studio and the flow of it becoming blurred into everyday life, having the option to make a move in a work of art at any point in the day or night. It’s a very different way of working, and it creates a different kind of work. You told me that when you were in Long Island, for example, you were working on small-format canvases—at least small for you. That was one change, obviously—the big canvases were by necessity relegated to the city studio because of the scale.

PSWhen I was in Long Island at the beginning of the pandemic, I just did drawings. I didn’t do paintings there. And I used to live in my studio, too, many years ago now. It was interesting, but I like having the studio separate. I like not having paint on everything. Although you’re right: waking up in the middle of the night and making a change on a painting can be very good and helpful. But changing my work never really leads to anything. I can add to it, but I can’t change it.

SSHas that always been the case?

PSNo, just for the last thirty years [laughs].

SSWhat happened thirty years ago that changed your work?

PSI discovered japonisme, and then I discovered Chinese literati paintings, and then I started to pour paint. When I started to pour paint, there was no return. You can’t unpour it; it’s there. I can start a new one, but I can’t change what I have. Like life.

SSI always like those paintings best where the humans in them are doing exceedingly prosaic things, like walking a cow or carrying straw, hidden and tucked away in the majesty of painting—specifically that extreme shift in scale from the profound to the mundane, dizzying, with no middle ground.

PSIt’s the same in your paintings, where often all the action is happening on a very small scale.

SSIs there a particular literati painting that you are tied to, or was it more of a philosophy?

PSWell, let’s say I generalized the philosophy [laughs]. I like a lot of different theories, but I was first attracted to the literati paintings—which are not the most highly esteemed, but perhaps because I’m a Westerner, they were easier for me to understand. What I like about them is very simple. The painting is five feet tall and there are mountains and water and moon and trees, and then at the bottom, you see a monk looking at the moon, and he’s half an inch tall—and that’s the landscape. He is depicted in eternity in the landscape, like how we all fit in.

I want to disappear from my art, and I hope the viewer will become the monk looking at the moon—the quantum of life.

Pat Steir: Paintings, Gagosian, Rome, March 10–May 31, 2022