Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

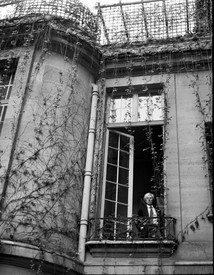

Cindy Sherman was born in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, and lives and works in New York. Considered one of the most influential artists of her generation, she came to prominence in the late 1970s with a group of artists known as the Pictures Generation. Sherman has participated in four Venice Biennales, cocurating a section at the 55th exhibition in 2013. Additionally, her work has been included in five iterations of the Whitney Biennial, two Biennales of Sydney, and the 1983 Documenta. She has been the recipient of the Praemium Imperiale, an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award, a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, and a Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship. Photo: Richard Phibbs

Derek BlasbergMy favorite part of the exhibition when I saw it in London was the re-creation of your studio.

Cindy ShermanFor the catalogue, they hired someone to photograph each wall in my studio and someone thought, “What if we make wallpaper out of it?” I had actually already been making wallpaper for a couple of projects, so we knew how to do it. I was scared I was going to hate it—what if it seemed super Disney-ish?—but they did a great job. There was talk of sending over some of my wigs or props or ephemera or stuff to put in that room too, but I’m glad it was all just fake rather than having some real precious little things there.

DBOne would assume artists are apprehensive about showing the tricks of the trade, but in a lot of ways your work is more about observing people than tricking them, right?

CSI like things to be clear. In my early stuff, you can see the cord that’s attached to the shutter when I’m taking the picture, or you can tell they’re fake tits or a fake nose. It doesn’t bother me.

DBIt was fun to see so many people taking selfies in this selfie studio too.

CSAfter we figured out that was what we were going to do, I realized this was going to be a great selfie place.

DBWhat do you think of people who compare your work to selfies or self-portraiture?

CSI don’t actually see any of the work I’ve done as self-portraiture. I always refer to those characters in the third person, not as though they’re me.

DBYou once said you hate the word “selfies.” Is that true?

CSThe thing I hate most about selfies is the way most people are just trying to look a certain way. They often look almost exactly the same in every pose, and it’s a pose that’s aiming to be the most flattering, which isn’t at all the way self-portraiture has traditionally been used—it was never about self-promotion or making one look one’s best, it was more about studying a face, using one’s own face to learn about portraiture in general when, I suppose, no other face was available. Also, I’ve always thought that phone cameras distort the face. The lens is slightly wide angle, which isn’t inherently very attractive anyway. I have friends I follow and I can tell when they’re feeling vulnerable or insecure because they’re suddenly posting all these pretty photos of themselves. They’re just wanting people to like them.

DBHow did you get on Instagram?

CSI’d been hearing about Instagram all the time but I didn’t really know what it was until I went on a trip to Japan with a friend and she insisted on doing it. I thought, “Well, I’ll just share photos of my vacation.” And then, slowly—it’s kind of fascinating how it creeps in—I got interested in discovering all these different sorts of subcultures, like people who do makeup but aren’t really makeup artists as I know them. It’s a whole separate art form that I wouldn’t have known about if it wasn’t for Instagram.

DBHow often do you post?

CSI was just thinking that I’m due for one. It’s been over a month or something. It’s more challenging now because I feel like I’ve done everything I can with these apps. I’m waiting for new things to explore or new things to discover.

DBHow do you find your apps?

CSWell, a lot of it is just people recommending things. And sometimes I rethink how to use an old app. The one I use a lot is Facetune. They have this feature where you can basically erase background and insert anything you want. If I want to make a shirt a field of grass, I can. Or a fire pit. Or whatever. I get bored when I feel like I’m just repeating a lot of what I’ve already done.

DBYou’re the only person I know who uses Facetune to make themselves look . . . can I say “ugly”?

CS[Laughing] That’s okay to say “ugly.” Funny looking? Or odd?

DB Let’s talk about your history. You were born in New Jersey and you moved as a young girl to Long Island. You were the youngest of five children. Apparently, as a little kid you liked to dress up.

CSI think a lot of kids like to dress up. But while most of my friends wanted to be brides or ballerinas or princesses for Halloween, I’d want to be a witch or a monster or an old lady. I don’t know why—to me that just seemed more fun, especially for Halloween, where it’s about being more scary than pretty. However, I’ve been in therapy for a few years and now I wonder if dressing up was also a way for me to forget about who I was and try to be somebody else. There was the idea of my family feeling like I didn’t fit in, so maybe if I was a different person they would accept me. Or something?

I think I was always interested in clothes and the idea of outfits and personas. When I was a teenager, I made little drawings of all my school outfits. I was inspired by this one teacher who seemed to wear a different outfit or configuration of outfits every single day. So I made a little pegboard with the five days of the school week on it and I made little paper dolls and I’d figure out all my outfits for the whole week with these little drawings. In college, I did a film based on the idea of those little outfits. It’s part of the show and called Doll Clothes.

DBI saw that but didn’t realize you’d done it in college.

CSCollege was when I went back to dressing up. Actually, now that I think of it, even before I documented it I was already playing with makeup in my room to look like different people for fun. Maybe it was also therapeutic.

DBDo you think dressing up as an adult unlocks childhood joy?

CSWell, it’s definitely still fun.

DBWhen did you start photographing yourself?

CSI failed my first photography course. I had to retake it and I had a teacher who was sort of, “Don’t worry about the technological part of it,” because that’s why I failed the first time [laughter]. Growing up, I was sheltered in terms of art experience. We rarely went to museums and I didn’t know a lot about contemporary art. Learning about Conceptual art and thinking about using a camera made it seem like, “Well, yeah, I could just worry more about what the concept is of the image I’m going to be shooting and then reproduce it in a second.” Whereas in the past the way I painted was very laborious.

DBTo pursue art as a career takes gusto.

CSHonestly, I didn’t know what it even meant to be an artist. When I went to college, I thought maybe I’d wind up teaching. I thought an artist was somebody who did the drawings in court, or on a boardwalk, you know, the people that did the caricatures?

DBWhen did you realize it could be a career?

CSI remember seeing a spread in Life magazine with Lynda Benglis pouring latex on her studio floor. I guess that was the first time I thought, “Well, hmm. This is really something a woman could do.”

DBDo you identify with any of the feminist movements shaping pop culture, like #TimesUp or #MeToo?

CSYes, definitely. It’s implied in my work. I don’t go around using the label or the hashtags, I’m quieter and I’d rather my work speak for me, but it’s definitely in the work.

DBAfter you graduated from college, were you excited to come to New York?

CSHonestly, I was kind of scared. Whereas most people would have gravitated to New York, I thought, “No, I’m not going to go to New York. You don’t have to go to New York to be an artist. You can be an artist anywhere!” I stayed in Buffalo one year longer after I graduated. New York intimidated me. Actually, it wasn’t until I was visiting the city and I saw Vito Acconci walking down the street in SoHo that I thought, “It’s such a small world here, it’s not a really big, intimidating place.” I realized the art world is such a small world, an insular world. Then I got this [National Endowment for the Arts] grant of $3,000 so we [me and the artist Robert Longo] thought, “Well, let’s move to New York!”

DB How were the early days in New York?

CSIt was great back in the ’70s. I guess the city was definitely grittier and dirtier and more dangerous, but way downtown was deserted. I lived in the Wall Street area and there was nobody out at night. You were lucky if you could find a cab. The whole art world was different in a positive way because there weren’t a lot of galleries, which there are now, and nobody really expected to sell their work. There was this freedom because you weren’t worried about anybody buying it, so you didn’t have that much pressure about what you were making. There was more of a crossover between types of creativity, too: a filmmaker could also be an artist, or a visual artist could also be a musician, or a stand-up comic could be a painter.

DBWhen you moved to New York, you made the now famous Film Stills. Was that on a lark or was that your stake in the ground?

CSI didn’t know what I was doing! At first, the way it started, I did one roll of film and on that roll of film I had six or seven different characters in different poses. There was the one on the bed in the black bra, there was the one leaning by the door as if she’s crying. I couldn’t afford film so I would only take six shots of each one of those and then decide, “Okay, that’s it, I have it,” and then do another one. For a long time, I worked in my apartment, just resetting up different areas—this place looks like a library or that place looks like a hotel room. When I realized I should do some exterior shots, I would make lists of what types of shots to do around the city and then ask a friend, at the time my boyfriend [Longo] . . . we’d get in his van, I’d have a few wigs and some outfits, and we’d go, “Okay, let’s stop here!” And I’d put the wig on and some makeup on and jump out and tell him where to stand to take the picture and then we’d jump in and I’d do a different character and we’d find a different place. It was fun!

DBThat seems so youthful and authentic.

CSIt was. I didn’t know if any of it was going to work out, but it didn’t matter! It was just, like, let’s have some fun.

DBI wonder if young people still have that sense of easy risk anymore. Today, we’ve got twenty-one-year-old self-made billionaires.

CSNowadays, kids go to grad school and leave expecting to find a gallery right away and have their first show. There are probably courses that teach them what it is to become a successful artist, rather than just concentrating on making the art.

DBWere there moments when you thought about not being an artist? If so, how did you keep on keeping on? Sorry if this sounds like a motivational speech.

CSThat would probably be the $64,000 question, because I think that just the fact that you don’t give up means that you’re probably set on being an artist. I met people who came to New York and wanted to be artists and after a year, they didn’t like struggling. They wanted a real job where they could have a decent apartment and not be in some funky shithole. I think when you’re really trying and committed, you kind of don’t care where you live. You allow yourself to live in shitholes.

DBIs your process now the same as it was then?

CSThe biggest difference is shooting with digital now. I can see instantly what I’m getting and what’s wrong—if it’s out of focus, or if I just don’t like the shot. And if I don’t like the character I can change the makeup. In the past, I’d develop everything after having done all the makeup and taken all the photos, and then I’d wait for the film to develop. I’d have to take my makeup off because I’d have to take the film to the store, so if I didn’t get the shot I’d have to start over again.

DBYou set up all the pictures yourself?

CSYeah. I have a mirror set up next to the camera.

DBYou do all of the hair and makeup yourself?

CSMm-hmm. I also have a little handheld mirror for when I’m doing the makeup.

DBDo you have music on?

CSYeah, I love music.

DBAnd you use a camera alone?

CSYes. I feel less inhibited with no one around, which means I can take chances and do something foolish and maybe that turns out great. It would be a lot more convenient if I had somebody there to stand in for me and I could see, “Oh no, it will be better if you tilt your head this way. Or stand up instead of sitting down.” But I just know it would inhibit me, that’s all.

DB Have you ever tried a photo assistant?

CSYes. I found I was kind of just keeping busy for them [laughs]. I felt like I had to look like I was really working all the time. I realized that part of my work process is about spacing out sometimes, and that’s sometimes good. It clears your brain for a little bit and then you go back to focusing and then your head’s a little clearer.

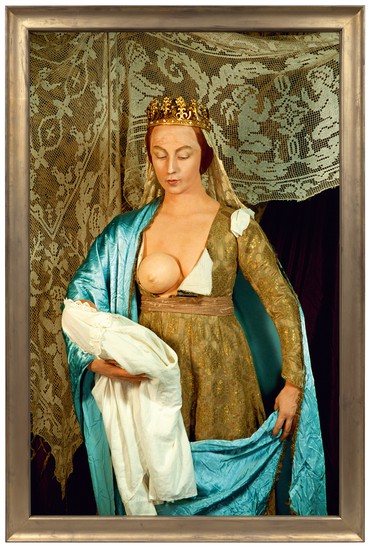

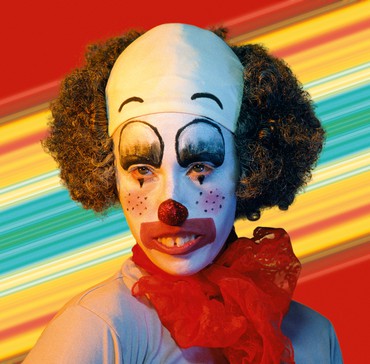

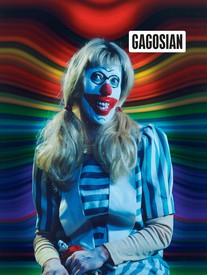

DB How do you research for your series, like the clowns and the socialites?

CS For the clowns, I started trying to imagine what the personality was underneath the makeup. What would bring somebody to want to be a clown? Is it just purely to make kids laugh? Or is it something else—is it a darker, seedier thing? Some of the snapshots of clowns I found online were these kind of seedy, sweaty-looking men. When I started doing this series I started thinking of clowns as a whole race of people, but people just like anyone else. I thought I should do a housewife clown, a clown at the gym . . . I was trying to think of everyday shots of clowns just going about life.

DBIs that a typical trajectory? You start with an article of clothing and that ignites a thought process?

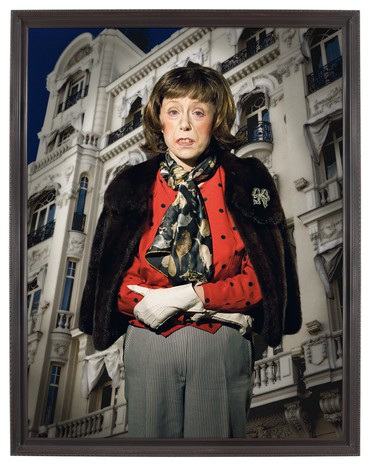

CSSometimes, yeah. The socialites series was inspired when I was going through thrift shops on the Upper East Side. I was inspired by the outfits because they looked like something a glamorous woman would have worn thirty years ago at some function up there.

DBDo you have multiple series going on at the same time?

CSUsually it’s really sequential. Sometimes, though, I might be fooling around in between series.

DBHas there ever been a picture where you’re like, “That’s just way too ugly”? You said I could say “ugly”!

CSNo, but I’ve done pictures where I think it’s just a little too goofy. I like ugly and bizarre, but not goofy.

DBDo you look at pop-culture references for starting points in your work? What’s the filter of your information?

CSWell, it’s a lot of cultural, cross-multicultural influences, like bad TV or bad movies or advertising or fashion photography. A lot of it is just imagery that’s in the media.

DBThere’s a certain sense of folly to your work, so you have to be aware of the Real Housewives . . . , right?

CSRight. Although I haven’t really watched that show. I’m vaguely aware of some of the characters. The recent stuff I did, which was loosely inspired by 1920s flappers, came from seeing portraits of women from that period in a German book. The makeup was so intense! I remembered that’s what I loved about that time period—the eyebrows being so extremely penciled in and the lips being little bow shapes and a dark hole around the eyes. I loved the whole extremeness. I began playing with it and the characters just came out.

DBOftentimes I think people are trying to show a more real version of themselves in this selfie culture. Are you showing real versions of yourself or unreal versions of yourself?

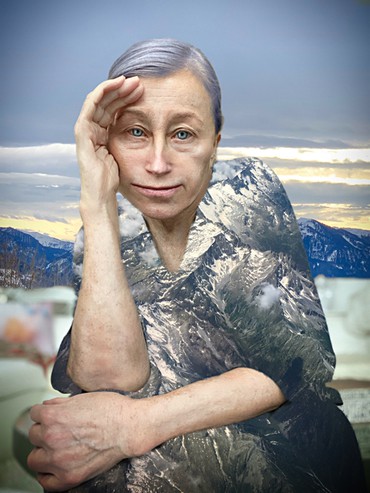

CSI would say they’re unreal versions of myself, but I don’t even see them as myself at all. I feel like I’m disappearing in the work, rather than trying to reveal anything. I’ve never thought of it as revealing fantasies or getting to feel this or that character. I’m hiding beneath the makeup, so it’s about obliterating, erasing myself and becoming something else.

DBSo it’s not even self-portraiture?

CSI’m trying to find other faces and other personalities. I don’t know what it is I’m looking for until I put the makeup on and then I sort of find it or it’s somehow revealed.

DBHow does it feel when you get to that place?

CSKind of magical. When I was doing some of the history pictures, I looked in the mirror and I didn’t see myself at all. That was really kind of freaky but also euphoric. I really did not see myself anywhere in her.

Artwork © Cindy Sherman