To Create a Vision: Jia Aili in Conversation with Philip Tinari

Jia Aili speaks with curator Philip Tinari about his arts education, his working process, and his desire to expand the talking points around painting.

Spring 2019 Issue

The artist speaks with the Quarterly about interrogating perceptions, questioning illusions, and the primacy of intuition.

Jia Aili in his studio, 2017–18

Jia Aili in his studio, 2017–18

Gagosian QuarterlyWhen you’re working, are you thinking about narrative in any sense? Or are the paintings intended to escape narrative-based readings?

Jia AiliI almost never have a narrative in mind when I’m beginning a work, I start out from pure intuition. But quite a few viewers discover narratives, particularly in the larger-scaled pieces. That made me realize that narrative is about a way of reading—a visual narrative is produced by the order of vision.

What a painting expresses depends on more than its image alone. I don’t think my paintings are born out of the emotion or feeling of a certain moment; I hope their meaning emerges from a more complete level. For me, the action of painting involves facing specific, delicate matters. I rarely make overall cultural assumptions, I prefer to focus on the relativity and absoluteness of painting, on using color, shape, and structure to create transcendental vision.

I have a portrait [Untitled, 2013] that adds a complete circle to the body of a normal model. At first glance, people usually mistake the figure for a man with a big belly. While that visual illusion may make them uncomfortable, it also stimulates them, wakes up their aesthetic processes. What should representational painting be today? What is our present reality, and what is the act of creating images? Those questions lead to another: what is the essence of being a painter? There are different opinions on that; my own is that the painter is the person most closely related before, during, and after the production of vision.

Jia Aili’s studio, 2017–18

GQIf you allow that viewers will come up with their own narratives in looking at your paintings, narratives beyond your control, is there anything you hope for from them—any way you’d like to see them respond?

JALWhen we’re looking at a figurative painting, our usual response is to focus on the perception created illusionistically rather than on the illusion itself. It’s the same in our daily behavior: people often use the perceptions created by illusion to understand and ponder the world and measure what they see. When we look at paintings, we need to broaden our perspective and see the illusion itself, or go farther and try to experience the whole process of illusion. That’s when we may really begin to understand painting.

Many paintings create illusions and ask people to live in those illusions, inadvertently and comfortably. Sometimes I want to make the illusion less comfortable, to inspire viewers to think. Discomfort induces doubts. If they can try to appreciate the artist’s most subtle and delicate perception and intention in the creative process, then when they look at works in different genres or forms, new perspectives and understandings will emerge.

For me, the painting process flows naturally along like the processes of life. It’s not a hierarchical progression. As long as life exists, experience will continue, and there will always be dilemmas. Once I thought painting meant solving issues little by little and making the work perfect, but now I realize that although you wanted to solve and improve, that’s impossible to achieve.

Speaking of how art reflects on human nature, my personal experience is that the process of painting involves the basic elements of painting. Every second involves interrogating the most profound and meticulous contemporary perception related to human nature. You’re in a state of total concentration. What I call perception or intuition is prior to logic. For an artist, that’s the key precondition.

Jia Aili’s studio, 2017–18

GQIs there any experience that remains central to you—something informing your work in a permanent way?

JALAfter graduating from Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts in 2004, I stayed there to teach. I was a young teacher and not many students were willing to listen to my views on art; they were busy grafting their knowledge of art onto strategies of success. Although I was curious about that, it also made me panic. That crisis slowly overwhelmed me and I felt I had to leave.

In the spring of 2007, I moved to Beijing, and settled near the city in a place called Black Bridge Village. There were people there from all over the country—migrant workers from remote areas, vendors, rock musicians waiting for contracts, released prisoners, psychics and living Buddhas, independent filmmakers, and of course artists like me, trying to make a living in Beijing. Their faces and eyes are still vivid to me today. We woke up every day to our own realities, or not so much our own realities but our common situation. I knew that countless people were leading such existences on Beijing’s outskirts, like besieging soldiers who could not yet conquer the city.

The Olympic flame came to Beijing in 2008, and while the fireworks shone in the sky, there were also tiny sparkles in our eyes. In that brief moment we seemed to have the pride and dignity that only people inside Beijing deserved. It was in that year that I began to create the oil-painting series We Are from the Century [2008–11].

In those years, while planting our own fields, we kept on observing the city. But eventually the real-estate coalitions of the city we thought we were going to invade swept us away. I lost my cheap rented studio, rolled up my canvases, and moved somewhere more marginal still. But I remember this group of people who really fell into art. They had an overpowering desire to take the reality around them as their subject, to keep trying for more far-reaching visual forms, and to surpass existing criteria of evaluation through the creation of works that were radical but still emotional. In the various ideas and values they acquired, they had the consciousness and integrity of true intellectuals.

So you can see that I have always been a marginal figure, but as an artist I prefer to see my work as based on looking, based on the gaze, because it makes me feel I mean something, although I still can’t tell you what painting is. A decade has passed in a blink of an eye and now I’m in New York again, where Bob Dylan, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and J. D. Salinger have all lived. But no matter how the situation changes, I want my art to retain the temperature of honesty.

GQIn the same way, is there any idea or principle you keep permanently in mind while you’re working?

JALWhen I’m painting, I’m always asking myself whether everything in front of me is true feeling and thought. Any kind of petit bourgeois emotional overflow will lead me into misunderstanding. In fact I’ve made many such mistakes, letting a work lose its granular sense of life and get pretentious, which disgraces my original intention.

Painters should be concerned with human nature, beginning with themselves. Work that’s mannerist, work that pretends to be simple—it’s all a disease. There’s no sincere experience in that kind of work; everything becomes affectation. Under cover of success, your intentions and beliefs have slipped away. If an artist loses his concern for human beings, he loses his reason to make art. That’s why we say that attitude supports method. Nowadays, I realize more and more clearly that the artistic concept I agree with belongs to humans rather than gods. As Nietzsche said, How can those who live in the light of day comprehend the depths of night?

Jia Aili’s studio, 2017–18

GQIn previous bodies of work, the religious or divine surfaces in diverse ways—in figuration and metaphor, for instance. Does religious thought factor into these new works?

JALMany of us today believe that we’re living at a turning point. While we’re grateful for the rapid developments we’ve seen in science and technology, they are quietly changing our aesthetics and our thoughts. Behind the many difficulties we face is a deep spiritual crisis: in contemporary society, the divine is fading away. People today are more and more inclined to see everything as a “resource.” A lot of literature and art conveys sadness, even despair, about the contemporary religious and humanistic status quo. The end of an era is the end of some ways of living and thinking, and the arrival of a new era may not necessarily bring peace and light.

Artwork © Jia Aili Studio; photos: Jia Aili

Jia Aili was born in Dandong, China, in 1979 and lives and works in Beijing. In 2004 he graduated from the New Representationalism Studio of the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts in Shenyang, China, where he subsequently taught from 2005 to 2007, before focusing exclusively on his career as a painter. He participated in the collateral events of the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011. Photo: Nan Lin

Jia Aili speaks with curator Philip Tinari about his arts education, his working process, and his desire to expand the talking points around painting.

This video presents a behind-the-scenes look at Jia Aili’s studio in Beijing. He elaborates on his in-progress works, the complexity of his compositions, as well as his philosophies of and motivations for painting.

Curator Shen Qilan speaks with the artist about his latest works.

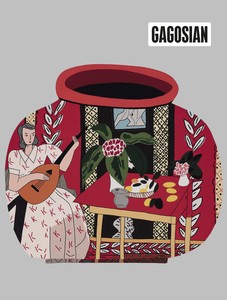

The Spring 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Red Pot with Lute Player #2 by Jonas Wood on its cover.

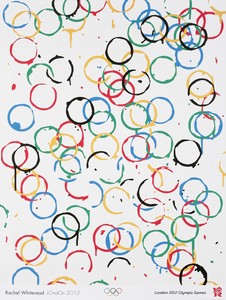

The Olympic and Paralympic Games arrive in Paris on July 26. Ahead of this momentous occasion, Yasmin Meichtry, associate director at the Olympic Foundation for Culture and Heritage, Lausanne, Switzerland, meets with Gagosian senior director Serena Cattaneo Adorno to discuss the Olympic Games’ long engagement with artists and culture, including the Olympic Museum, commissions, and the collaborative two-part exhibition, The Art of the Olympics, being staged this summer at Gagosian, Paris.

On the occasion of Art Basel 2024, creative agency Villa Nomad joins forces with Ghetto Gastro, the Bronx-born culinary collective by Jon Gray, Pierre Serrao, and Lester Walker, to stage the interdisciplinary pop-up BRONX BODEGA Basel. The initiative brings together food, art, design, and a series of live events at the Novartis Campus, Basel, during the course of the fair. Here, Jon Gray from Ghetto Gastro and Sarah Quan from Villa Nomad tell the Quarterly’s Wyatt Allgeier about the project.

Art for a Safe and Healthy California is a benefit exhibition and auction jointly presented by Jane Fonda, Gagosian, and Christie’s to support the Campaign for a Safe and Healthy California. Here, Fonda speaks with Gagosian Quarterly’s Gillian Jakab about bridging culture and activism, the stakes and goals of the campaign, and the artworks featured in the exhibition.

An interview with Marcantonio Brandolini d’Adda, artist, designer, and CEO and art director of the Venice-based glassware company Laguna~B.

In celebration of the life and work of Frank Stella, the Quarterly shares the artist’s last interview from our Summer 2024 issue. Stella spoke with art historian Megan Kincaid about friendship, formalism, and physicality.

Multi-instrumentalist, singer, songwriter, and composer Lucinda Chua meets with writer Dhruva Balram to reflect on the response to her debut album YIAN (2023).

Lonnie Holley’s self-taught musical and artistic practice utilizes a strategy of salvage to recontextualize his past lives. His new album, Oh Me Oh My, is the latest rearticulation of this biography.

Richard Armstrong, director emeritus of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation, joins the Quarterly’s Alison McDonald to discuss his election to the board of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, as well as the changing priorities and strategies of museums, foundations, and curators. He reflects on his various roles within museums and recounts his first meeting with Frankenthaler.