Jay DeFeo

Suzanne Hudson speaks with Leah Levy, executive director of the Jay DeFeo Foundation, about the artist’s life and work.

November 12, 2020

Alice Godwin explores the shifts in Jay DeFeo’s practice in the 1970s, considering the familiar objects that became recurrent subjects in her work during these years and their relationship to the human body.

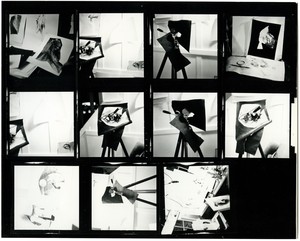

Jay DeFeo, contact print of photographs taken in her studio in Larkspur, California, 1976

Jay DeFeo, contact print of photographs taken in her studio in Larkspur, California, 1976

When Jay DeFeo transformed the screened porch of her home at 29 Millard Road in Larkspur, California, into a studio in 1969, she had been without a devoted space for making art for nearly four years. This break in her creative practice followed her completion of The Rose (1958−66)—a landmark work of encrusted impasto so colossal, it required a forklift to extract it from DeFeo’s San Francisco apartment. With The Rose’s departure, DeFeo felt she needed time “to restore some kind of equilibrium.”1 Among the subjects that drew her back to the studio during the 1970s were an array of curiosities from daily life—a pair of swimming goggles, a shoe tree, a broken tape dispenser, erasers from her studio. Comforting to DeFeo and at ease in their surroundings in Larkspur, these familiar objects gradually filled constellations of drawings, paintings, photographs, and photocollages. Not only intimately connected to the body through their scale, form, and use, they also seemed to possess multiple personalities, like close friends, with their own desires and needs.

Jay DeFeo, Untitled, 1976, gelatin silver print, 10 × 8 inches (25.4 × 20.3 cm)

Perhaps the most anthropomorphic of these items was a tripod, which played a crucial role in DeFeo’s eager experiments with photography between 1970 and 1976. During this period, DeFeo photographed her studio and the humble objects that occupied it with zeal, propelled by advice on making prints from her students at the San Francisco Art Institute and the darkroom she had constructed in Larkspur. DeFeo’s photographs are a visual diary that exposes the tensions between the objects and the works in progress that lined the studio walls and reveals the profound influence of these items upon her practice. A contact sheet from 1976 demonstrates in particular how the tripod’s appearance and character, as well as its relationship with neighboring paintings, drawings, and other objects, changed: at times it seems whimsical and lighthearted, at others elusive and threatening. DeFeo referred in her diaries to her “tripod person,”2 and in her photographs its protruding limbs appear to mimic a pair of legs strolling across the studio. Shrouded in a piece of paper—cut, washed, and draped over the mechanical body to dry—the tripod appears to personify a man or a woman, clothed in a “dress”3 or “a pin striped suit.”4 A photograph from 1976 shows the tripod as an eerie hybrid of human and machine—the central stem a figure standing to attention and dressed in folds of paper, the circular mechanism a single, all-seeing eye.

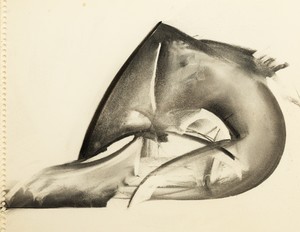

Jay DeFeo, Untitled (Eraser series), 1979, charcoal on paper, 11 × 14 inches (27.9 × 35.6 cm). Photo: Robert Divers Herrick

While in some photographs the tripod resembles its source, in others it strays into an unfamiliar landscape of light and shade. DeFeo wrote, “Gradually [the Tripod works] assume their own reality—it’s never the one I expect. . . . Sometimes [I] wish I had more control over the destiny of my images.”5 In this reality, the tripod’s image drifts into potent abstraction while remaining rooted in an organic language of bodily form. DeFeo relished the ambiguous beauty of these shapes, stating, “Hopefully, even the most literal drawings among the recent work transcend the definition of objects from which they are derived.”6 Comparably, in DeFeo’s Untitled (1979), from her Eraser series, inspired by a vast collection of erasers gathered over years in the studio, voluptuous lines of charcoal and areas of grisaille are juxtaposed with strips of blank paper to suggest the corporeal body of the eraser—transformed into an enigmatic mountain range or a pliable, writhing figure.

Jay DeFeo, Crescent Bridge I, 1970–72, acrylic and mixed media on plywood, 48 × 66 ½ inches (121.9 × 168.9 cm), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, purchase with funds from Daniel C. Benton. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson

Jay DeFeo, Untitled (Shoetree series), 1977, graphite, acrylic, and charcoal on paper, 16 × 13 inches (40.5 × 33 cm). Photo: Robert Divers Herrick

The relationship between DeFeo’s subjects and her own body is particularly explicit in Crescent Bridge I and II (both 1970–72)—her first significant paintings of the 1970s. Though not immediately discernible, the stimulus for these mysterious, lunar-like landscapes was DeFeo’s own dental bridge, which she described as a model “out of my own head.”7 Equally, DeFeo’s works based upon shoe trees dangling from wire in the studio are inherently connected to the body through their supple curves and their function as surrogates for feet. Dana Miller, curator of DeFeo’s 2013 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, suggests, “DeFeo gravitated toward subjects that conveyed the vulnerability of the body” as well as “objects bearing wounds or signs of age”8 —inspired, possibly, by the worn patina of the historic buildings she encountered in Europe in the early 1950s. Never is this more apparent than in Trap (1972). In this luscious painting, a moth has been ensnared on the surface of a celestial crescent—a poignant moment of chance transfixed in the wet surface of the acrylic that provides the subject, focus, and title of the work. Representative of the viewer, perhaps, or the artist herself, the creature is both physically and psychologically lost within the painting.

Jay DeFeo, Trap, 1972, acrylic, graphite, and moth on Masonite, 25 × 22 ¾ inches (63.5 × 57.8 cm)

Jay DeFeo, Figure V (Tripod series), 1976, graphite and acrylic on paper, 13 ⅞ × 11 inches (35.4 × 27.8 cm). Photo: Robert Divers Herrick

DeFeo often spoke of her phenomenological approach and its foundation in bodily experience.9 With this in mind, representations of quotidian items like the tripod conjure a particular bodily sensation, as in Figure V (1976). Here, a dark vacuum of graphite and swaths of luminous acrylic recall DeFeo’s experience of crawling through the prehistoric caves of Lascaux and Altamira in northern Spain during her sojourn to Europe. In a letter to Fred Martin, a classmate at the University of California, Berkeley, DeFeo wrote about the works inspired by this experience, saying that she wanted to “live in” them.10

DeFeo engaged with the objects she depicted on an intimate scale, handling and moving them with care around the studio. A fragment from a piece of jewelry she had made as a young artist, which served as a model for a series of works in the 1970s, intrinsically bears the trace of her hand and presence, though the original object is veiled almost from recognition at times in sweeps of grisaille paint, graphite, and charcoal. Similarly, DeFeo’s erasers, which she referred to as “testimonial to my mistakes,”11 were imbued with the imprints and residue of her touch; kneaded between fingers and thumb, and passed between hands, these objects accrued meaning over time.

Jay DeFeo, Untitled, 1979, color photocopy, 14 × 8 ½ inches (35.6 × 21.6 cm)

Jay DeFeo, Untitled (Jewelry series), 1977, acrylic, charcoal, graphite, and ink on paper, 20 × 15 inches (50.8 × 38.1 cm). Photo: Robert Divers Herrick

DeFeo’s ritualistic technique of constructing and deconstructing her image, with erasers or solvents like household cleaning fluids, speaks to the essentially physical and bodily nature of her process. Notably, for DeFeo, the act of removing marks was just as important as making them. “I have an additive and subtractive necessity,” she explained. “I’ve always got to get down there and show what is underneath everything.”12 DeFeo would treat her blank paper with a layer of sprayed acrylic so that it could “receive a lot of abuse without giving up”;13 pushing her image to the edge of extinction and back again, she believed that “you have to destroy a little bit in order to build a little bit.”14 The charged tension between mark-making and erasure fosters a riotously tactile surface in DeFeo’s work, which oscillates between the recognizable object and pure abstraction. DeFeo’s transition from oil to acrylic during the 1970s equally demonstrates the bodily sensation of her practice. In contrast to the sculptural relief of oil—at its most compelling in The Rose—acrylic required DeFeo to continually work the surface of her chosen medium in order to foster the same sense of volume and space. Without the inherent physicality and weight of oil, DeFeo now faced the challenge of conjuring three dimensions in light and shade by manipulating the paint, a process that forged an intimate bond between the material and the artist’s hand.

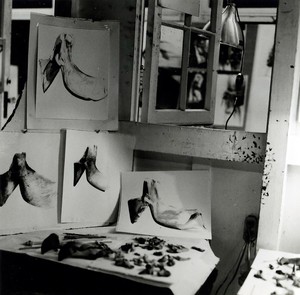

Drawings from the Eraser series in progress, photographed by Jay DeFeo in her studio, Larkspur, California, 1980

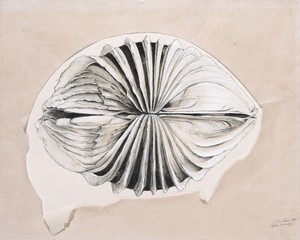

Through her repeated, physical engagement with materials, DeFeo moved beyond the external body to a deeper language of symbolic form. Working from an “objective reality toward an inner reality,”15 as she described it, DeFeo infused her drawings with memories and emotions that were entrenched in the experience of their making. Just as The Eyes (1958) foreshadowed a change in DeFeo’s vision before embarking upon The Rose, After Image (1970)—one of the first pieces she completed in Larkspur—speaks to a new relationship between object, body, and eye. Based on a photograph of a costate cockle, After Image refers in its title to the ghostly remains of an image on the inside of the eyelid, evocative of the way in which DeFeo was now looking to her own “inner reality” and that of her subjects. As Judith Dunham noted in a 1978 Artweek article, DeFeo had begun to extract “spiritual, metaphysical meaning from her scrutiny of common objects.”16

Jay DeFeo, After Image, 1970, graphite, tempera, and acrylic with cut and torn tracing paper on paper, 14 × 19 ½ inches (35.6 × 49.5 cm), The Menil Collection, Houston, gift of Glenn Fukushima. Photo: Paul Hester

By harnessing the resonance of familiar items, DeFeo exposes an inner landscape of unspoken desires and emotions, in keeping with the Surrealist notions of “convulsive beauty” and the “magical circumstantial.” André Breton and his followers proclaimed the irresistible, subconscious pull of found objects, and sifted through the flea markets of Paris for objects that were the incarnations of dreams or the realization of clandestine needs. Similarly, as curator Corey Keller writes, DeFeo “used photography to record the convulsive beauty of the world around her.”17 By capturing the array of ordinary items that filled her studio and her relationship with them, DeFeo could be said to have exposed the hidden topography of her own subconscious.

While indelibly connected to the body through their rich tapestry of sensual material and surface, the humble objects that captivated DeFeo during the 1970s negotiate a tightrope between the tangible and the transcendent, the outer and the inner, the figurative and the abstract. As reality plunges into a mystical language of symbolic form, familiar acquaintances like the tripod, the shoe tree, and the eraser come to represent the body—both physical and metaphysical.

1 Jay DeFeo, oral history interview by Paul Karlstrom, June 3, 1975–January 23, 1976, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

2 Jay DeFeo, private journal, February 8, 1976, Archive of The Jay DeFeo Foundation, Berkeley, CA.

3 Jay DeFeo, slide lecture, Mills College, Oakland, CA, December 2 and 4, 1986, Archive of The Jay DeFeo Foundation, Berkeley, CA.

4 DeFeo, private journal, August 27, 1976.

5 DeFeo, private journal, May 19, 1976.

6 Jay DeFeo, conversation with Henry T. Hopkins, June 23, 1978, quoted in an untitled text by Hopkins in Matrix 11 (brochure; Berkeley, CA: University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley, 1978).

7 Jay DeFeo, quoted in Lauren Schell Dickens, “Through the Aperture: The Circular Approaches of Jay DeFeo,” in Undersoul: Jay DeFeo (San Jose, CA: San Jose Museum of Art, 2019), p. 14.

8 Dana Miller, Outrageous Fortune: Jay DeFeo and Surrealism (New York: Mitchell-Innes & Nash, 2018), p. 12.

9 David Pagel, “Digging In, Spreading Out,” in Jay DeFeo: The Ripple Effect (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2018), p. 11.

10 Jay DeFeo, letter to Fred Martin, n.d., Fred Martin Papers, Reel 1128, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

11 DeFeo, slide lecture, Mills College, 1986.

12 DeFeo, slide lecture, Mills College, 1986.

13 DeFeo, slide lecture, Mills College, 1986.

14 DeFeo, oral history interview, 1975; quoted in Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, “When Material Becomes Art,” in Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), p. 83.

15 Jay DeFeo, lecture, University of California, Santa Cruz, May 10, 1989, Archive of The Jay DeFeo Foundation, Berkeley, CA.

16 Judith L. Dunham, “Memorable Visions in Drawing and Sculpture,” Artweek, June 28, 1978; quoted in Sidra Stich and Brigid Doherty, “A Biographical History,” in Jay DeFeo: Works on Paper (Berkeley: University Art Museum, University of California at Berkeley, 1989), p. 23.

17 Corey Keller, “My Favorite Things: The Photographs of Jay DeFeo,” in Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), p. 75.

Transcending Definition: Jay DeFeo in the 1970s, Gagosian, San Francisco, September 10–December 11, 2020

Artwork © 2020 The Jay DeFeo Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Alice Godwin is a British writer, researcher, and editor based in Copenhagen. An art-history graduate from the University of Oxford and the Courtauld Institute of Art, she penned an essay for the exhibition catalogue Damien Hirst: Fact Paintings and Fact Sculptures and has contributed to publications including Wallpaper, Artforum, Frieze, and the Brooklyn Rail.

Suzanne Hudson speaks with Leah Levy, executive director of the Jay DeFeo Foundation, about the artist’s life and work.

David Cronenberg’s film The Shrouds made its debut at the 77th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in France. Film writer Miriam Bale reports on the motifs and questions that make up this latest addition to the auteur’s singular body of work.

The mind behind some of the most legendary pop stars of the 1980s and ’90s, including Grace Jones, Pet Shop Boys, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Yes, and the Buggles, produced one of the music industry’s most unexpected and enjoyable recent memoirs: Trevor Horn: Adventures in Modern Recording. From ABC to ZTT. Young Kim reports on the elements that make the book, and Horn’s life, such a treasure to engage with.

Louise Gray on the life and work of Éliane Radigue, pioneering electronic musician, composer, and initiator of the monumental OCCAM series.

Tracing the history of white noise, from the 1970s to the present day, from the synthesized origins of Chicago house to the AI-powered software of the future.

Ariana Reines caught a plane to Barcelona earlier this year to see A Sea of Music 1492–1880, a concert conducted by the Spanish viola da gambist Jordi Savall. Here, she meditates on the power of this musical pilgrimage and the humanity of Savall’s work in the dissemination of early music.

Dan Fox travels into the crypts of his mind, tracking his experiences with goth music in an attempt to understand the genre’s enduring cultural influence and resonance.

Charlie Fox takes a whirlwind trip through the Jim Shaw universe, traveling along the letters of the alphabet.

On the heels of finishing a new novel, Scaffolding, that revolves around a Lacanian analyst, Lauren Elkin traveled to Metz, France, to take in Lacan, the exhibition. When art meets psychoanalysis at the Centre Pompidou satellite in that city. Here she reckons with the scale and intellectual rigor of the exhibition, teasing out the connections between the art on view and the philosophy of Jacques Lacan.

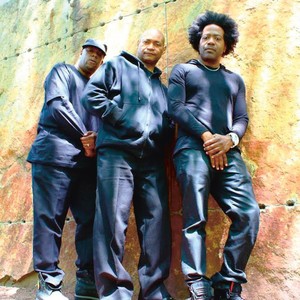

Dieter Roelstraete, curator at the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society at the University of Chicago and coeditor of a recent monograph on Rick Lowe, writes on Lowe’s journey from painting to community-based projects and back again in this essay from the publication. At the Museo di Palazzo Grimani, Venice, during the 60th Biennale di Venezia, Lowe will exhibit new paintings that develop his recent motifs to further explore the arch in architecture.

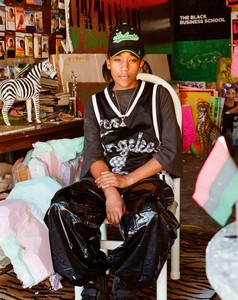

Essence Harden, curator at Los Angeles’s California African American Museum and cocurator of next year’s Made in LA exhibition at the Hammer Museum, visited Lauren Halsey in her LA studio as the artist prepared for an exhibition in Paris and the premiere of her installation at the 60th Biennale di Venezia this summer.

Michael Cary explores the history behind, and power within, Nan Goldin’s video triptych Sisters, Saints, Sibyls. The work will be on view at the former Welsh chapel at 83 Charing Cross Road, London, as part of Gagosian Open, from May 30 to June 23, 2024.