I can’t remember a time when I didn’t wish to be different, to be anything or anyone other than what I already am. I think it’s like this for all seers. We’re cursed with too much knowledge, and let me tell you, no one thanks us for it. The future was never meant to be unfurled the way we do it, as if it were an armful of ribbons dropped to the floor, rolling out into iridescent and dangerous paths. No matter what people claim, the truth is that it’s better for them if you leave it knotted and obscure, tight in the present.

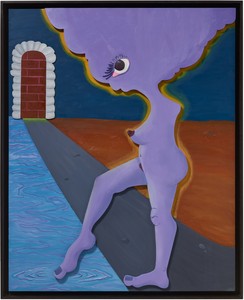

Seers like me, we ruin all of that. We whisper dreamed-up secrets, heavy predictions, and the world bends around our words. When people brush against our skin, they feel the electric glow of a reality being made or unmade, and I see how deeply they recoil, down to their souls. I don’t blame them. Everything in them is hissing to pull away before the power burrows under their skin, before it changes them as well. I am being changed in every waking and dreaming moment, watching as the threads of fate glitch and shift around me. Given all this, it is no surprise that all seers eventually go mad, but here is a poorly kept secret—sometimes, the people around us go a little mad as well.

You must understand, it’s difficult to witness a thing like me. People want to hold the reins of a future that’s already bucking out of control, because there’s nothing more terrifying than feeling helpless in the face of a prophecy. You can’t blame the prophecy, but you can blame the tongue it fell from. If you controlled a seer, could you control the futures leaking out their mouths? How far will you go to keep them on a leash?

My mother used to warn me to be careful. “They’re too afraid to kill us,” she whispered. “But never forget—everyone knows what happens when you let a seer live.”

I miss her still.

She would lie with me under a new moon and sing quiet songs. She told me I was spun out of the sky itself, that when she laid her cheek next to mine, she could hear the call of birds wheeling against an impossible horizon. She said that when I smiled as a baby, rain fell beneath her feet and lightning wrapped itself around her ankles. When I look into a mirror now, I see all her stories in my flesh—the way my hair holds a lifting monsoon, storms tugging at the nape of my neck. When I speak, all the versions of who I have ever been and who I will ever become speak with me. I sound like a cathedral possessed by ghosts, and I swear, one of them sounds like her.

I no longer have a name. Maybe I had one in a different life, maybe my mother once murmured soft syllables over my head, but whatever it was has sloughed off by now, a lavender skin dying quietly in a back room.

No one addresses me directly. They can barely even look upon my face, terrified of the knowledge they’ll find there. When they come begging for a prophecy they’ll regret, they sidle like cowards and approach me around corners, with half their backs turned for a mercy I cannot give. Everyone is afraid of things like me, you understand, but they are too afraid to leave us alone.

Back when our neighbors first discovered what I was, after my mother died, they drove me down to my knees in our front yard and carved out one of my eyes. I remember the fluid running down my cheek, shockingly cold, and the buzzing in my ears. I did not scream. I didn’t understand the point of the excision—losing one eye changed nothing about me and everything about them. All the futures in my vision shifted over to my remaining eye and burst into even brighter colors. When I looked up at the crowd, I saw the blood drain from their faces as they began to understand, as they backed away without taking my other eye. A seer’s power cannot be destroyed or punished, not even by death. A blind seer is even more powerful than a mutilated one, but every alive seer sees too much.

I tried to stay silent for years, thinking that if I said nothing, perhaps people would simply forget what I was. If I folded into thin sheets and slipped between the crowds, fluttering through their streets, making myself into an inconsequential wisp, maybe then they wouldn’t be so terrified. Maybe then they wouldn’t pick up their blades and their foaming fears and hunt me down again like a crawling animal. In another story, perhaps this silence would have saved me, but I was young, and I was a seer, and all the truths I could see piled up behind my teeth, clanging against the enamel. I tried to push them back, swallow them down my crowded throat, but the visions screamed and clawed their way back up, gouging my tongue. When I let them free, the people seized me and stripped me and threw me in here.

There is nothing but earth and a road that goes nowhere. The doorway is sealed, and I can see the light of a community that wants nothing to do with me seeping through underneath. I am still myself, radiant with knowledge and horrifically alone, and sometimes I wonder if things are better this way, keeping them away from me and me away from them. I close my eye and play games of possibility. Perhaps I am free. Perhaps I never belonged there anyway. My visions are cruel—they tell me nothing about where I will end up, they leave me to make that choice naked and uninformed. The water runs by the road, and when it sings, it sounds just like my mother. She would scold me for not imagining widely enough.

Perhaps the door is not the only door. The water sings, and when I look down into it, a world unfolds within my eye. Storms hum against my scalp and I take a step. Perhaps I am free.

Perhaps there will be a name waiting for me.