Salomé Gómez-Upegui is a Colombian-American writer and creative consultant based in Miami. She writes about art, gender, social justice, and climate change for a wide range of publications, and is the author of the book Feminista Por Accidente (2021).

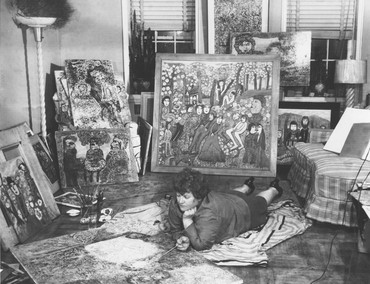

Jennifer Higgie is an Australian writer who lives in London. Her latest books are The Mirror and the Palette: Rebellion, Revolution, and Resilience: Five Hundred Years of Women’s Self Portraits (2021) and The Other Side: A Story of Women in Art and the Spirit World (2023).

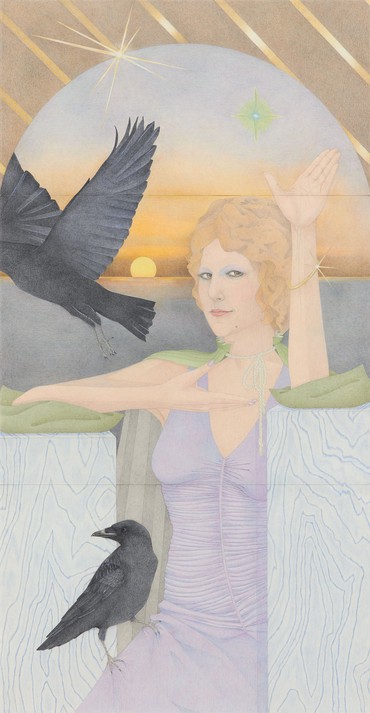

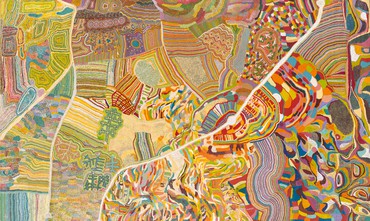

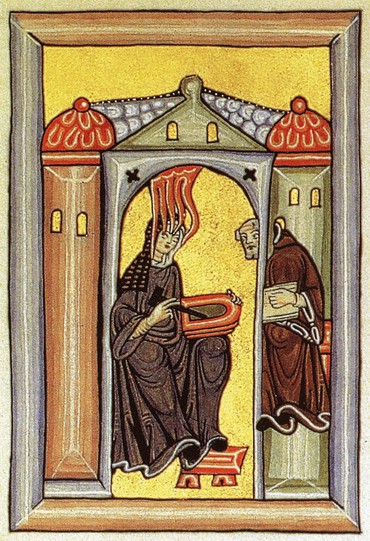

“To trust in art is to trust in mystery,” writes Jennifer Higgie in The Other Side, a riveting amalgam of memoir and art history that explores the potent and unearthly connections between female artists and that which we cannot explain. Delving into the lives of creative mystics who have long left the physical world, such as Hildegard of Bingen, Hilma af Klint, and Agnes Pelton, Higgie’s book is delightfully pertinent, as many contemporary artists, like Carolina Caycedo, Loie Hollowell, and Emma Talbot, are drawing on spirituality to deepen the reach of their practices. Indeed, as Higgie makes manifest, creating and appreciating art is often an act of pure faith that involves abandoning rationality, indulging in the enigmatic, and leaning into the ethereal.

Salomé Gómez-Upegui I’d love to start with a question about the process of writing the book. I heard you say in an interview that it was a weird and intense time. How so?

Jennifer HiggieSome of it I explain in the book, but I’d been at Frieze magazine for twenty-three years, and then I left at the end of 2019. I went to Australia, where I’m from, and we were fine, but we got caught up in those catastrophic bushfires, and that was like being in an apocalypse. It was horrible. Then I came back to London and the pandemic hit. It was just weirdness and horror after weirdness and horror.

I’d been deeply involved with art for a long time. I’d been an artist myself; my training was at art school. And I feel that—I’m sure you know this—when you work for a magazine, the pace of everything becomes so fast. You’re making snap judgments all the time; you’re walking into a show, and within three seconds thinking, “Is this good, is this bad, should we cover it, are they hot, are they not”—dreadful. So I needed to discover a kind of re-enchantment with art.

The research I’d done for my previous book, The Mirror and the Palette [2021], kept leading me to this idea of the exclusions of art history, namely gender exclusions, but also to this narrative that had helped enrich modernism. Spirituality had been written out of the story, and I became interested in that. Also, for the first time, I was bringing myself into it—my own need for a kind of re-enchantment.

SGUCan we talk a bit about your childhood and how spirituality played a role in your life growing up?

JHThat’s a very good question, and I don’t think of myself as particularly religious. I grew up in a Christian family, and my parents were Presbyterians, so we went to Sunday school and to church, but it was very easygoing. My father, who died seven years ago, was a beautiful man, and he always prayed every night and said prayers with us. And for him, the idea of God or spirituality was a very benevolent one, a very kind thing. And as a gambling man, he said, “Well, why not pray? It makes you feel better, and if you die and you go to heaven, that’s great, and if you die and there’s no heaven, you don’t know anyway.” So there was a certain logic there.

I wasn’t particularly religious, and I’m not Presbyterian anymore, and I wouldn’t call myself a Christian. But I’ve always believed in greater powers, whatever they are, and I’m very interested in theology, in belief systems that enrich and empower people, not oppress and exclude them, obviously. And I’d always believed in ghosts, not as a big deal, like, “Oooh, ghosts,” but, “Yeah, I sort of feel there are spirits around us.”

I guess I could say I’m a bit of an animist. I believe in the power of nature, the power of animals, and the goodness in people.

SGUAnd how did your relationship to the subject change while working on this book and consciously thinking about this for a while?

JHI think that when I was at Frieze and working more with art criticism, my instinct was to question everything, to challenge everything, to look at it from every angle. But with this, I decided to keep an open mind and keep my judgment at bay, and sort of look deep into this well and see what I saw there. I mean, can you imagine walking around the National Gallery and looking at Renaissance paintings and thinking about artists from the perspective of a skeptic? “Oh, look at that Titian. What a fool he was to believe in angels.” Or to look at First Nations art in Australia and say, “Well, I don’t believe them, I don’t believe that they believe in these origin myths.” It would be such an impoverished way to live. I decided to look into it and see what these people came up with, and try as much as I could to understand what they were doing from their own perspectives.

And especially in the nineteenth century, so many spiritualist groups, especially of women—none of them, anywhere in the world had any kind of political agency. There was literally no female suffrage, and they were living in deeply entrenched patriarchal societies. Spirituality gave them a voice and a space to explore other ways of being in the world. Who am I to say, “It was bunkum, and they were just fooling themselves”? For whatever reason and however they did it, it gave them a voice. It enriched their lives, it gave them a sense of community, and many of them made great art out of it. I’m not going to judge that.

SGUYou manage to be so objective about these controversial topics in the book. And there’s been a resurgence of this topic in the art world recently, right? So many artists are being more open about their own spiritual beliefs or about how these things inform their practices. It’s also giving way to new, unexpected visual languages. I think the phrase you use in the book is “spirits are back in favor,” which I thought was funny. Why do you think that is?

JHI think there are a few answers to that question. When I went to art school in the 1980s and 1990s—this was in Australia—French theory, especially poststructuralist theory, was very much in vogue. And if you mentioned words like instinct, intuition, imagination, or spiritualism, you would have been laughed out of the room. At that point, it was all about deconstructing everything—the death of the author and so on.

We were taught to break everything down, and in a funny way, I think that’s one of the reasons I stopped painting. I became so suspicious of my own impulses and intuitions that I felt slightly frozen by the whole thing; I couldn’t necessarily justify it.

But now, there’s no such orthodoxy—I don’t think—in art schools, which is great. There are still critical discourses, but there’s a much greater appreciation for many different ways of understanding and interpreting the world. If someone in art school says they’re into spiritualism or guided by their religious beliefs, that would be respected; it wouldn’t be criticized.

Another thing: a bit like around the time of the First World War or the American Civil War, both of which were times of great tragedy and loss and grief, people started looking at different ways of understanding the world. And I think there’s a great distrust now around governments, around political parties. We’ve seen so many dreadful leaders, so much corruption and so much patriarchal tradition still embedded in things like politics and belief systems. Many are thinking let’s explore different ways of being in the world.

And in the same way that in the late nineteenth century a lot of spiritualists were interested in science, scientists and physicists still say that we don’t fully understand what time is. So it’s not like we know these things. And art is a wonderful way to explore things that can’t necessarily be rationalized or fully understood. I think there’s a much greater respect now for First Nations knowledge and Indigenous ways of understanding the world. In Australia, it’s changed massively over the last few decades—for the better.

SGUBut to what extent could this be a fad, or have there been enough conversations that it might be here to stay?

JHI think that there are too many different ways of understanding this kind of art and making this kind of art for it to be a fad. Also, it’s not like it’s a monolithic thing.

SGURight.

JHYou’ve got women who are exploring goddess theory; you’ve got First Nations belief systems; you’ve got artists who are Buddhist or Hindu or Christian or believe not in a fixed orthodox religion but in something more about energies or dreams or the unconscious. I don’t think it’s a fad, because there are too many different strands to it, too many ways of it being manifested in the world.

SGUI’d like to pivot again into the creative process—there’s so much beautiful imagery in the relationship you had with the ocean while writing the book. How did setting influence your writing process?

JHI wrote part of it in Greece. This island I love going to, Amorgos, is so beautiful and peaceful. Its landscape is dramatic; its water is extraordinary; its people are so kind. It’s an amazing place. I remember I was going through quite an anxious period writing the book, because I wasn’t sure how autobiographical it should be—should I just get rid of the autobiography and make it a history of spirituality in art? But just being there, the physical presence of the island, the sense of myth that you get very clearly there, and the role of women in Greece all affected me. I was reading Madeline Miller’s Circe, which I love, and a lot of great myths, and Homer as well.

So I set myself a little exercise: at the end of every day, I would write my reflections on what it was like that day and what I was doing. And I gave myself permission: “It doesn’t have to go in the book if you don’t want it to in the end. Don’t think too far ahead, just go day to day and write these pieces.” So I did that, and then those bits ended up being in the book. And I also thought, who doesn’t love reading about being in Greece [laughs]?

SGUYes. I feel like there were points in the book where the subjects were a bit heavy, and these descriptions of the setting are just a breath of fresh air.

JHI’m so glad you noticed that because that’s exactly what I felt. I felt that they were a breath of fresh air. I trained as an artist, not as an academic, and I didn’t want to write a book that was a sort of faux-academic treatise. I wanted to write something that was very personal and my own journey of curiosity through this material.

SGUYou talk about art specifically, but do you think that writing, music, theater, and other art forms are also in some way spiritual practices, or do you think that they’re different?

JHObviously there are close connections with music, I think, in terms of [creating] something from nothing. With the act of composing, however much you’ve been taught, there’s an element of, where did that melody come from, where did that structure come from? I think that’s very closely aligned with art. And that’s where people like Hildegard of Bingen are so fascinating. She was an artist, she was a composer, she was a naturopath, she was a botanist—all of those things.

I think that in all creative spheres, there’s an element being a sort of medium. It’s funny that when you’re an artist, people ask, “What’s your medium,” meaning, “Are you a painter or a sculptor?”—I’d never really noticed that before I wrote this book. Now I hear it all the time. “What is their medium?”

SGUOr who is their medium?

JHWho is their medium, exactly. Any great act of writing, I think, is a form of mediumship as well. I mean, Duchamp famously said that the artist is a medium, and I think that it doesn’t make any difference if you’re writing a play or painting a picture, there’s always a mediumistic aspect to creation.

SGUI want to end going back to something you said earlier, that when you left Frieze you were looking for re-enchantment. Would you say that you found it?

JHOh—[laughs]. I think that I’m finding it. No one’s asked me that before. That’s a very good question. It was terrifying leaving Frieze, on many levels. Or scary, anyway. Whenever you change your life, it’s scary. But there’s good fear and bad fear, in the same way that when I get a shiatsu massage the practitioner will say, “This is good pain. This is good pain.”

When you need to change your life, and it’s good scary, only a kind of enchantment can come out of that. I still feel like I haven’t fully got there. And at the moment, I’m trying to work out what my next book will be, and it’s sort of driving me crazy, because I know it’s there, but I can’t quite see it yet. So I’ll channel the spirits to show me what the next book will be.

Photos: courtesy Pegasus Books

The US edition of The Other Side is available for preorder through Simon & Schuster (Pegasus Books, January 2, 2024)