From rakatá to rakatá

Any book, exhibition, library, museum, or text that tries to organize visual arts production by geographical focus is a fallacy. Whether this artistic-geographical reflection be based on a neighborhood of a small town or an entire continent, the equation will always be open to question—what are the criteria? What is the historical frame? Why this artist and not that one?

Experienced in the field of publications of this comprehensive nature related to the visual arts, the British-American publisher of Austrian origin, Phaidon Press, commissioned the present book that brings together more than three hundred artists associated with Latin America. An organizational criterion is to dedicate this book to artists born or who spent a considerable part of their lives in regions that today have Portuguese and Spanish as their official languages. . . .

Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, different agents of the visual arts system have emerged in the form of artists, critics, historians, curators, museum directors, gallerists, and auctioneers, among many other activities. They invented dynamically different notions of what we could consider “Latin American art.” The discussions certainly bring us more questions than answers: should we call “Latin American” all the art that takes place in the current territories of South America, Central America, Mexico, and part of the Caribbean? What would be the characteristics of this production? What are the boundaries between identities based on the idea of a nation and others that deal with the larger region? Would it only include artists who explicitly demonstrate elements of belonging to the region’s cultures through representation? Would there be room for artists born in the area whose works do not explicitly state their affiliation with Latin America due to their “abstract” character? What could we say about the immigrant artists who went into exile in the region? And what about artists born in Latin America but whose production matured in other parts of the globe? How do the artists born in the United States who are first- or second-generation children of immigrants fit within this conceptual-geographical umbrella? Is every “Latinx” artist also a “Latin American” artist? How far can you stretch the texture of an identity? . . .

The only certainty when circumscribing the identity of any place is that something will always be missing. On the other hand, the discussions of more than a century that led to the solidification of the idea of Latin American art were essential in forging a notion of collectivity that made possible encounters, publications (such as this one), exhibitions, and institutions of the most varied types. . . .

To respond to the challenges of this transhistorical book, Phaidon contacted a group of advisors related to the region. These researchers come from different generations, work from opposite perspectives, and live in contrasting places. This diversity certainly contributes to the inclusion of not only the most prominent names when we think about “Latin America,” but also very young artists in an initial process of institutionalization or even those considered “B-side” in the historic artistic narratives of the region. Including artists from each of the twenty countries and territories that compose this Latin America, speaking hundreds of languages of the original peoples, as well as Portuguese and Spanish, the following pages are a kaleidoscopic introduction to art in the region.

—Raphael Fonseca

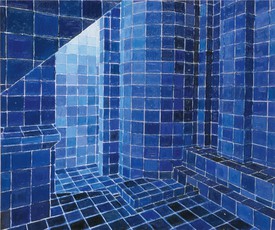

Adriana Varejão

Born 1964, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Lives Rio de Janeiro

With her image-oriented poetics and her use of visual symbols, Adriana Varejão is at odds with the post-Minimal, post-Conceptual art common among Brazilian artists of her generation, which has given her practice a distinctive character. Varejão is a painter above all else, even when she creates three-dimensional pieces. Painterly components are key for works that take their inspiration from Brazilian vernacular imagery, such as the traditional blue Portuguese tiles and eclectic ornaments of local architecture, as seen in Ruína Brasilis. In line with the Brazilian notion of Antropofagia (transcultural appropriation), Varejão reinterprets images from across the globe, stating in a 2016 interview with Ocula Magazine that “I don’t create images, I use images that exist somewhere in the world.” During her visits to Mexico in the mid-1990s, she was impressed by the display of produce in the butcher’s shops, which drove her to contrast the decorative surfaces of sculptures that resemble ruined architectural elements with innards painted like raw meat, as though an inner organism had popped out when the “skin” of the architecture was torn off. The resulting tension between geometry and organic matter alludes to life, death, and violence in a disturbing way.

—Gerardo Mosquera

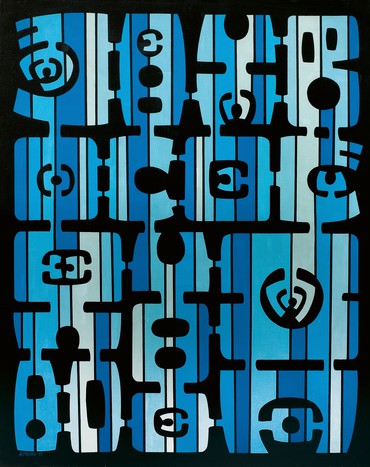

María Freire

Born 1917, Montevideo, Uruguay. Died 2015, Montevideo

An early proponent of geometric abstraction in Uruguay, María Freire greatly contributed to its national popularity as an artist, critic, and educator. In 1952, she cofounded the Grupo de Arte No Figurativo de Montevideo—in which she remained the sole woman member despite the group numbering nineteen artists by 1955—with the painter José Pedro Costiglioli (1902–85), whom she later married. Their creative and conjugal partnership proved prolific, the pair formative in processing regional abstraction in Montevideo and Buenos Aires. In both art and writing, Freire traced the developments of modernism in the Southern Cone (a subregion of South America, mainly below the latitude of the Southern Tropic), notating the influence of post-war industrialization in Uruguay. Indeed, many of her paintings and sculptures owe their materiality and formal precision to industrial products and processes—acrylic paint, plastic sheeting, the application of synthetic lacquers, and the mechanical bending of steel. Freire’s oeuvre is notable for its stylistic idiosyncrasies: from spare compositions to canvases saturated with forms and colors; hard-edged geometry to more sensuous, organic lines. Appearing as obscure pictograms striate by chromatic bands of color, Variante No. 115 is characteristic of Freire’s mid-career engagement with optical vibrancy and curvilinear structures.

—Lucienne Bestall

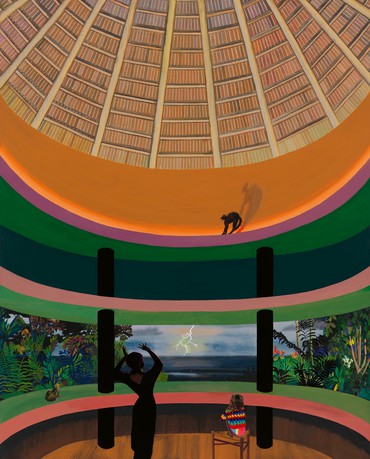

Hulda Guzmán

Born 1984, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Lives Santo Domingo and Samaná, Dominican Republic

Hulda Guzmán’s vibrant, lush tableaux reimagine the spectacular scenery of the Dominican Republic as a stage on which larger-than-life human figures, anthropomorphized animal characters, and mystical objects come alive in an evocative dance. Informed by a wide range of references, from ancient Chinese art and Japanese Ukiyo-e to the work of Vincent van Gogh (1853–90) and Henri Rousseau (1844–1910), her persistent muse is the landscape of her home country. Working in both its picturesque capital, Santo Domingo, and from a remote, Modernist bungalow designed by her architect father on the wild mountainous terrain of Samaná on the northeast coast, the artist’s studio and home often feature in her works, with a motif of windows suggesting a symbiosis between outside and interior, between human activity and the rhythms of nature. In Delightning, Guzmán’s Samaná studio provides a dramatic view to the stormy sky outside, as lighting strikes the ocean. The primal emotional tension is heightened by two figures in the foreground, the woman’s arms thrust up in alarm, the child curled up, contemplative, or afraid. As Guzmán explained on the occasion of her 2022 solo exhibition at Stephen Friedman Gallery, London: “I feel that being in nature connects us to the deeper wisdom of life.”

—Charlotte Jansen

sAndra Eleta

Born 1942, Panama City, Panama. Lives Portobelo, Colón, Panama.

A self-described photographer and “advocate for freedom,” as a student in New York, Sandra Eleta studied fine arts at Finch College and took courses at The New School of Social Research and the Institute of Contemporary Photography. Returning to Panama in the mid-1970s, Eleta made work highlighting neglected narratives and immortalizing the people of her native country. In her series La servidumbre, the artist turned her camera on domestic workers in the Canal Zone, making visible the groups in Panamanian society—often women—who were otherwise largely overlooked elsewhere in visual culture. Eleta’s pointed and complex portraits, of which Edita is a memorable example, subvert expectations and explore the personal impact of this period of occupation by the United States. Edita, clothed in her housekeeper’s uniform, holds a feather duster across her chest like a scepter and, with a regal gaze, turns her employer’s gilded chair into her throne. Wearing an expression that is at once resigned and proud, she directly challenges the hierarchy of her social status and asks the viewer to examine their own relationship to social and political issues.

—Elizabeth O’Rourke