Black Futurity: Lessons in (Art) History to Forge a Path Forward

Jon Copes asks, What can Black History Month mean in the year 2024? He looks to a selection of scholars and artists for the answer.

Summer 2024 Issue

Dieter Roelstraete, curator at the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society at the University of Chicago and coeditor of a recent monograph on Rick Lowe, writes on Lowe’s journey from painting to community-based projects and back again in this essay from the publication. At the Museo di Palazzo Grimani, Venice, during the 60th Biennale di Venezia, Lowe will exhibit new paintings that develop his recent motifs to further explore the arch in architecture.

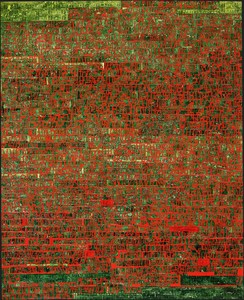

Rick Lowe, Diplopia, 2023, acrylic and paper collage on canvas, 72 × 192 inches (182.9 × 487.7 cm)

Rick Lowe, Diplopia, 2023, acrylic and paper collage on canvas, 72 × 192 inches (182.9 × 487.7 cm)

When a fortunate age of pure production has ended, reflection enters, and with it an element of estrangement.

—Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling, The Philosophy of Art, 1859

We’ll stand our problems all in a row / Watch them fall like dominoes.

— Donald Byrd, “(Fallin’ Like) Dominoes,” 1975

I

For well over three decades, Rick Lowe’s name has been closely associated with the social-practice paradigm in contemporary art. The Houston-based artist helped pioneer this activist and in many ways quintessentially American offshoot of Joseph Beuys’s famed Soziale Plastik, or “social sculpture”—the most widely feted example of which continues to be his Project Row Houses (1993–2018), an arts-and-culture community project located in his adopted hometown’s historical Third Ward.

The story of Lowe’s rise to prominence as one of the primary practitioners of said paradigm has become relatively well known by now, but it justifies summary recounting nonetheless. Born in Russell County in rural Alabama in 1961 as the eighth of twelve children, Lowe grew up on a sharecropping farm, where, somewhat improbably and incongruously, he began to develop a talent for drawing in his teens (exposure to art of any kind, let alone art education, was conspicuously absent from Lowe’s upbringing). In an interview with the Wall Street Journal published in September 2022, Lowe recalled how “my artistic side awakened just after I turned six, when I chose a cotton crop sack based on its bright orange material.” In that same interview, Lowe reminisced about how, starting in his early teens, although he “wasn’t artistic yet,” his talent was emerging: “I could draw states and copy images of presidents.”1 Mapping, in short, has been a foundational element of art’s appeal for Lowe since the very beginning—and cartography a key component in his conception of art as a mode of knowing and navigating the world. Lowe was an avid basketball player in his youth, and he has been an ardent basketball enthusiast ever since. His athleticism landed him a scholarship to Alabama State University. He then transferred to Columbus College in Georgia, where he enrolled in a drawing class and first felt fully immersed in a creative environment. Further encouragement from observant and supportive teachers deepened Lowe’s exposure to art and art history—a crucial early art-making class instructed him in the basics of landscape painting—and sometime in the early 1980s, the fledgling artist started making his first paintings, based on protest signs and similarly charged political imagery. (Growing up in the South between Montgomery and Tuskegee, both in Alabama, and Atlanta, Georgia, Lowe was inevitably molded, however indirectly, by the protest culture of the civil rights era. It is sobering to think, in this regard, that the infamous Tuskegee Experiment wasn’t discontinued until the early 1970s, well after the cresting of the civil rights movement, and around the time of Lowe’s adolescence.)2

Continuing his practice as a politically engaged painter, Lowe moved to Houston in 1985 and increasingly involved himself with activist, community-building work in the city’s historically Black Third Ward. However, a chance encounter with a young visitor to his studio—who asked the artist, upon seeing paintings dealing with a wide range of racial injustices, “If you’re so creative, why don’t you come up with actual solutions for our problems?”—fatefully altered the course of Lowe’s trajectory, compelling him to give up on painting and decisively shift his focus to art’s potential for effecting real change in the social world. (The confidence and determination with which Lowe decided to take up his youthful visitor’s challenge is part of what makes his brand of social practice a “quintessentially American offshoot of Joseph Beuys’s Soziale Plastik”: a stronger and more pragmatically minded belief in “art’s potential for effecting real change in the social world” than ever animated the rivaling paradigm of relational aesthetics, for instance, which may retrospectively be theorized as Europe’s ludic foil to social practice’s earnest can-do ethos.)3

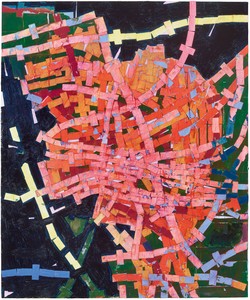

Rick Lowe, Untitled, 2023, acrylic and paper collage on canvas, 72 × 60 inches (182.9 × 152.4 cm)

The rest, as they say, is art history—the best-known chapters of which have become decisively entwined with the recent cultural histories of the sites in which they were (and often continue to be) rooted, as the following list of Lowe’s signature projects attests to: Project Row Houses in Houston (1993–2018); the Watts House Project in Los Angeles (1996–2001); Transforma Projects in post-Katrina New Orleans (2005); the Anyang Public Art Program in South Korea (2010); the Victoria Square Project in Athens (2016); the Greenwood Art Project in Tulsa, Oklahoma (2020); and most recently—the occasion for my own deepening acquaintance with Lowe’s work—Black Wall Street Journey in Chicago (2020–21). Place names, in short—“places and spaces”—have come to define Lowe’s founding contribution to the development of social practice as an art form rooted in community engagement and participation, in conversing, dialoguing, and relating—a living art of “pure production” made for, by, and with “others.”4

II

Almost three decades after Lowe abandoned painting in favor of a conception of art that afforded him a more direct sense of actively helping to shape the world around him—a conception of art, that is, as a species of problem solving—it is tempting to regard his return to art’s most archaic and canonical form (as well as its most individualistic and marketable) with some trepidation, even suspicion. It is not necessarily an admission of defeat, of course—Lowe was originally trained as a landscape painter, after all, so this “return” effectively signals a homecoming of sorts—but a kind of retrenchment. Why pick up the paintbrush again now? (“Now” being a time of excessive economic investment in the umpteenth of painting’s revivals.) The answer to this question is implied, in part, in the title of Lowe’s most ambitious monographic exhibition as a painter to date—Meditations on Social Sculpture, organized at Gagosian, New York, in the early fall of 2022—in the suggestion, that is, that his return to painting has allowed Lowe to (finally?) take stock of three decades’ worth of work made outside the studio and out on the streets. Lowe has chosen the private art of painting, in other words, to better “meditate” on the public art of his social sculpting.

Nowhere is it written that these two art forms should exist in a state of mutual exclusion. Painting operates here as a species of afterthought: as a way of visually thinking through the legacy of community projects from the artist’s past—as evinced, for instance, in the use of photographs documenting Project Row Houses in some of the large-scale paintings included in Meditations on Social Sculpture. An exhibition of Lowe’s works on canvas that I curated at the University of Chicago’s Neubauer Collegium in October 2022 was similarly titled Notes on the Great Migration. Lowe likes to think of his painterly practice as deeply reflexive, responsive, ruminative—an impression that was naturally enhanced, in the case of the suite of works on view at the Neubauer Collegium, by the scroll-like paintings’ graphic, scriptural character, i.e., their physical appearance as jottings and scribbles, the secretive, coded writing of extended notes to selves.5

All that said, it is hard to resist the temptation—especially given the sheer number of paintings Lowe has produced in the past few years—to frame this “return” to what is in essence a solitary studio practice and exclusively indoors activity within the larger context of the covid-19 pandemic, and its corrosive impact on socially engaged art practices and strategies in particular. For many months it was impossible for Lowe to physically meet the people who are so integral to his larger-scale, socially complex community projects. This was nowhere felt more keenly than in the case of the Black Wall Street Journey project, much of the findings of which went on to visually inform the contents of Notes on the Great Migration.

If the art market appears in such robust health emerging from the depths of a public-health crisis that has otherwise affected the public life of the global art world so disastrously, it is in large part because the pandemic unwittingly reinforced the perfect conditions for the flourishing of the oldest, toughest, and most economically viable of studio practices—namely, painting. We surely all remember at least one painting acquaintance rhapsodizing about the forced isolation of the pandemic’s early days, expressing their gratitude for the sudden luxury of long days of uninterrupted studio time: the perfect circumstances for the flowering of the most asocial of art practices. In any case, a spectral sense of the lost sociality of the covid-19 years resonates in the central “sculptural” gambit of Notes on the Great Migration. Eight of the paintings in that exhibition were placed horizontally on glass-covered tabletops, and the tables could be moved about in such a way as to allow the assembly of a much larger meeting table—of the kind one could easily imagine being central to the process of launching a complex community project. Indeed, on the handful of occasions when actual meetings were conducted, behind closed doors, around this meeting table, a real sense of the prickly question of the possible applications of art—of art’s presumed social use value—came back to haunt the site of Lowe’s art.

Lowe’s paintings are the work of an artist compelled, because of a variety of circumstances, to look back upon a lifetime devoted to public art—but they are also the work of a self-described workaholic who refused to allow the demands of social distancing to halt his “social works” entirely.6

III

Lowe’s newfound faith in front of the canvas—a renewed confidence in the power of imaging as well as of symbolizing—was obviously not achieved overnight. In fact, the artist’s interest in drawing and painting was first reignited in the mid-2010s, sparked, interestingly enough, by his growing preoccupation with the visual language of dominoes. Dominoes continue to be omnipresent in the artist’s work. Lowe’s first works on paper after more than two decades away from the two-dimensional realm of “mere” representation and symbolization were quick sketches of domino games whose snaking patterns had piqued the artist’s aesthetic interest. Those familiar with Lowe’s world will be aware of the importance of dominoes as a social tool within it—as the social practitioner’s primary implement and/or bonding element.

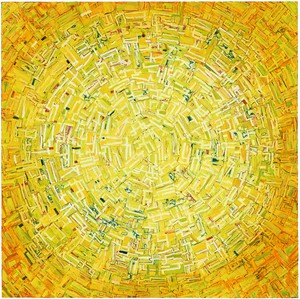

Rick Lowe, Untitled, 2023, acrylic and paper collage on canvas, 48 × 48 inches (121.9 × 121.9 cm)

Lowe is as obsessive about playing dominoes as he is about work more generally, and playing dominoes has long been integral to the chemistry of his “social work” in particular. Allow me to quote the following fragments from Lowe’s sole published artist statement:

The paintings and drawings I make are deeply rooted in the experience of what I call “domino culture.” While dominoes are a board game like many other board games played around the world, I find that dominoes in particular generate a kind of culture in communities where they are played. Dominoes are part chess, part checkers, and part contact sport. They have the contemplative element of chess along with the rapid maneuvering of checkers, but unlike most board games, dominoes are often slammed to the table with great force, highlighting the physicality of the game. For me, the culture is informed by the sounds of the dominoes clacking on the table (in places where dominoes has generated a culture, it’s not a silent game), the boisterous bluffing to gain advantage, and most important to me, the beautiful shapes that form as the dominoes are laid out. . . . I’ve also learned that dominoes is oftentimes a kind of academy where much is taught and learned. I feel fortunate to have been a student of many great thinkers who may be locked out of traditional academic institutions. These thinkers have keen eyes, ears, and minds to what is happening in many areas of life that range from the social, political, to the economic.7

This is a reference, in part, to the informal use Lowe has made of dominoes to both build relationships—as well as, more recently, works of art—and to better understand the relationships undergirding certain communities. (Lowe often played dominoes on the street with Jesse Lott, a well-known assemblage artist and pivotal figure in Houston’s Black art scene, whose mentorship was instrumental in the founding of Project Row Houses.)8

Lowe’s artist statement continues:

From the start of my playing in the early 1990s, I was fascinated by the shapes and patterns made throughout the game, but it wasn’t until I played with black dominoes on a white table that I could really see the distinct quality of the shapes. Eventually I started taking photos of these shapes on the tables. During this time, I was not making traditional art objects, but I was asked to make a drawing for an exhibition. For this exhibition, instead of photographing the shapes, I decided to trace the shapes after each game—a way of recording the different games as layered patterns. This led to a fascination with the abstract forms that emerged from the multilayering. I found it interesting how layering the patterns of the shapes of such a logical and ordered game could result in a complex narrative formed from the everyday activity of a game. My interest in the phenomenon ultimately led to the domino drawings that I create.

And concludes:

I did not know the reason I was drawn to tracing the domino patterns until one day I realized that the patterns were simply mapping knowledge of the time I spent with the people I played with. Because of the presence of mapping in the early domino drawings, I continued to make the work as an investigation into how mapping domino games could help me better understand the mapping related to my interest in urban development and other social and political realms.9

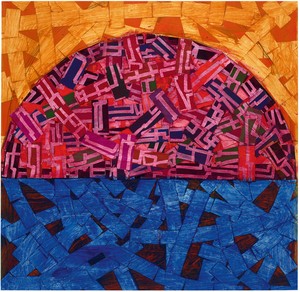

I’ve already mentioned the tabletops that served as an idiosyncratic mode of display for Lowe’s paintings in the context of Notes on the Great Migration. Those tables, each measuring three feet by three feet, are perfectly suited for domino playing, and close scrutiny of the paintings’ surfaces reveals the contours of dozens of snaking domino patterns. In fact, one group of four paintings in this constellation is titled Notes on the Great Migration: South, while the other is called Notes on the Great Migration: North, and the traces of domino lines fanning out from south to north are obviously meant to echo the dynamic of northward movement—from rural Alabama to Chicago, say. The Notes on the Great Migration: North panel contains three broad swaths of blue that clearly reference the Great Lakes, whereas the hues of green dominating the Notes on the Great Migration: South panel presumably allude to the South’s agricultural economy. (The snaking domino lines are train tracks as well as “trains of thought.”) Much like so many of Lowe’s recent paintings, in other words, these are really maps that resound with the artist’s thirty-year experience navigating urban environments and large-scale landscapes of all kinds, invoking associations with anything ranging from the everyday imagery of the fraying fabric of our inner cities to the intricately woven webs of diasporic and migratory patterns. The fact that these paintings use the cut-up book covers of histories of the Great Migration as their primary building blocks—Isabel Wilkerson’s much-lauded The Warmth of Other Suns, from 2010, is only the best-known title in this library—alongside Lowe’s signature domino stones helps to dramatize their discursive charge as “notes” of some sort, as the literal marginalia scribbled across these sprawling histories’ pages, or as marks on a map of one’s own making.10

In addition to mapping and writing, finally, another frame of reference for our reading of Lowe’s paintings can be found in the aesthetic of data visualization—in the kinds of graphs and statistics used to illuminate the types of economic histories that are so close to Lowe’s heart. Taken together, these paintings resemble a suite of blindingly colorful concrete poems dedicated to the vagaries of city life—a map of both city and country as delirious palimpsests made up of past, present, and future tenses.

Rick Lowe, Untitled, 2023, acrylic and paper collage on paper, 30 × 30 inches (76.2 × 76.2 cm)

IV

Speaking of the future, I want to conclude these reflections on Lowe’s return to painting on a seemingly minor linguistic note, one having to do with the artist’s preference for the language of “projecting” (Project Row Houses, the Watts House Project, Transforma Projects, the Victoria Square Project, the Greenwood Art Project, etc.). Indeed, encountering the notion of the project time and again while navigating the wilds of Lowe’s social-practice portfolio—none of his paintings, for obvious reasons, are called “projects”—I was reminded of an essay published in 2002 by the Russian art theorist and philosopher Boris Groys: “The Loneliness of the Project,” one of the defining documents of millennial art culture. Starting off with the dramatic claim that “the formulation of diverse projects has become the major preoccupation of contemporary man” and that “these days, whatever endeavor one sets out to pursue in the economic, political or cultural field, one first has to formulate a fitting project in order to apply for official approval or funding of the project from one or several authorities,” Groys maintains that “above all else, each project strives to acquire a socially sanctioned loneliness.”11 That is to say, the formulation of a project requires a certain degree of conscious long-term isolation that is nowhere more generously accommodated, it often seems, than in the contemporary art world. This is partly why Groys believes that “in the past two decades [starting in the 1980s, in other words] the art project—in lieu of the work of art—has without question moved to center stage in the art world’s attention.” (Lowe’s social practice belongs to a first generation of art-world developments that corroborates Groys’s hunch.)

The exemplary solitude of the artist is a function of the centrality of “project management” to contemporary art practice—and the artist’s career (“trajectory”) has become the supreme project that demands 24/7 management. Groys continues, “Each project is above all the declaration of another, new future that is supposed to come about once the project has been executed. . . . If one has a project—or more precisely, is living in a project—one always is already in the future.”12 I reread Groys’s visionary text with all the ambiguities and complexities of Lowe’s return to the studio in mind. That is the subject of this essay: the image of the prototypical social practice pioneer, alone in front of the canvas, trying to make sense of pasts and futures alike—all the while seeking solace in the solitude of social work as seen from the painter’s remove. I think.

1 Rick Lowe, quoted in Marc Myers, “Rick Lowe Went from the Fields of Alabama to a Solo Exhibit,” Wall Street Journal, September 6, 2022.

2 Tuskegee was the closest Alabaman city to Lowe’s childhood home. The experiment that is so fatefully bound up with its name was officially known as the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” a scientific investigation led by the United States Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 1932 until 1972. The main purpose was to observe the effects of syphilis when left untreated. The scandal of the experiment resided in the fact that syphilis had effectively become treatable as early as the mid-1940s, and that none of the participants in the study (which led to the avoidable deaths of more than 100 individuals) were ever informed of the nature of the experiment.

3 The trailblazing German Conceptualist Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) first developed the now-canonical notion of “social sculpture” in the late 1960s, formulating the well-known Beuysian motto “jeder Mensch ist ein Künstler” (Everybody is an artist) in 1967 as its founding creed. The term “relational aesthetics” first appeared in the context of the exhibition Traffic, curated by Nicolas Bourriaud at the CAPC museum of contemporary art in Bordeaux, France, in 1996, and was further developed in Bourriaud’s book of that name, published in 1998. (The vast majority of works invoked in Esthétique relationelle were made in the first half of the 1990s, mostly by European artists.) However schematic the distinction, much of the contrast in ideological emphasis between the two Beuysian legacies resides in the opposition between “social” practice and “relational” aesthetics—a dialectic not without geopolitical overtones in the juxtaposing of Anglo-Saxon and “continental” traditions, respectively, in the adjoining realms of social thought and theory. It is quite telling that Lowe’s work is hardly ever discussed in the latter terms. (To further dramatize the aforementioned transatlantic dialectic, one could make the case that the Ronald Reagan–era dismantling of the welfare state hastened socially minded American artists’ embrace of social practice, while Danish, French, and German artists continued to dabble in aesthetic debates in the false sense of security guaranteed by the seeming inviolability of the European social-democratic contract.) Indeed, one could argue that the founding moment in Lowe’s turn toward social practice—meeting a teenager whose simple question, in Lowe’s own phrasing, just “pulled the rug out from under my whole career up until that time”—required a wholesale repudiation of the aesthetic. And it is precisely this aesthetic impulse, as we shall see, that has made a dramatic return to the forefront of Lowe’s practice of late—as anything repressed is sooner or later wont to do, perhaps, no matter how counterintuitive its social logic.

4 Places and Spaces is the title of an album released by the jazz trumpeter Donald Byrd in 1975 that features the song “(Fallin’ Like) Dominoes,” which I have quoted in the second of this essay’s epigraphs.

5 It was illuminating to learn, upon visiting the artist in his Houston studio in the spring of 2022, that one of the books that made the deepest impression upon him as a young man—a book, moreover, that he continues to reread in older age—is Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, the sixth-century classic of melancholy thought. An undeniable charge of melancholy thought permeates Lowe’s use of painting as a tool for reflecting upon the inheritance of the artist’s activist past. It is this “blues”—a mood powered by gnawing doubts about the powerlessness of art as much as by its more widely touted opposite—that informs my use of the Schelling quote at the beginning of this essay, which alludes to a long history of presumed tension between making art and overthinking the making of art. The classic Hegelian hypothesis about the “end of art” states, pace Michael Inwood, that “thought[s] about art, and philosophy of art, arise only when art is in decline,” and that “reflective thought is inimical to artistic creation and impairs the art into which it intrudes.” Michael Inwood, introduction, in Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics (London: Penguin, 1993). Hegel and Schelling could not have anticipated that a whole new chapter in art history would be written based on the understanding that artistic creation can be a form of reflexive thought (even if it remains limited to reflecting upon artistic creation alone). This, in my view, is what Lowe’s paintings propose to “do,” and their reflexive labor—looking back, somewhat wistfully, upon some of social practice’s finest achievements—is what constitutes the consolation of art for Lowe and artists like him.

6 Social Works is the title of a group exhibition curated by Antwaun Sargent at Gagosian in the summer of 2021, which led to Lowe joining Gagosian’s artist roster shortly afterward. Considering “the relationship between space—personal, public, institutional, and psychic—and Black social practice,” and timed to coincide with “today’s cultural moment, in which numerous social factors have converged to produce a heightened urgency for Black artists to utilize space as a community-building tool and a means of empowerment,” the exhibition also featured the work of David Adjaye, Theaster Gates, Titus Kaphar, Carrie Mae Weems, and others. The timeliness of naming an exhibition Social Works was not lost on those aware of the tremendous loss inflicted on the art world by the demands of social distancing and self-isolating amid the covid-19 pandemic, and there was some poetic justice to be salvaged from the fact that when Lowe’s solo exhibition opened at Gagosian, New York, in September 2022, it turned out to be a densely packed, major “social” event indeed.

7 Rick Lowe, “Artist Statement,” in Rick Lowe: Paintings & Drawings 2017–2020, exh. cat. (Houston: Art League Houston, 2020), p. 5.

8 Lowe generously took me to meet Jesse Lott in his studio during my visit to Houston in March 2022. It is interesting to view Lott’s protean, sprawling brand of assemblage art through the same “relational” prism I am using here to theorize Lowe’s use of dominoes: as an art, in essence, of connecting and relating. In an interview published by Artnet on the occasion of Lowe’s exhibition at Gagosian, the artist reminisced about his early days exploring “professional” options living in the South. Having left Alabama and Georgia behind, he briefly lived in Biloxi, Mississippi, and “of course had the idea that I should, like every artist, go to New York. I thought about it and I’m such a country guy, I can’t handle cold weather. I thought about LA but then I said, maybe Dallas”—which later became Houston. “It was such a weird place, it was desolate. It had a rawness to it that I could really connect to. It felt very Southern in a sense, and almost rural in some of its urban pockets.” Needless to say, Houston’s subtropical climate is conducive to a very different variety of socializing than that of New York (or Chicago, for that matter), where the conditions for year-round open-air domino games do not obtain in quite the same fashion. Lowe, in Folasade Ologundudu, “‘That Just Shattered Things for Me’: Rick Lowe on the Moment He Realized His Art Had to Escape the Studio to Have Real-World Impact,” Artnet, September 19, 2022. Available online at https://news.artnet.com/art-world/rick-lowe-interview-social-practice-2177583 (accessed February 29, 2024).

9 Lowe, “Artist Statement.”

10 Other titles visible underneath the patchwork of Lowe’s painterly scrawls and scribbles are Blair Imani’s Making Our Way Home: The Great Migration and the Black American Dream (2020); Jacqueline Woodson’s This Is the Rope: A Story from the Great Migration (2013); James N. Gregory’s The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (2005); Alferdteen Harrison’s Black Exodus: The Great Migration from the American South (1991); and James Grossman’s aptly titled Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration (1991). As Lowe’s first solo exhibition in Chicago, Notes on the Great Migration is inspired in part by the midwestern metropolis’s hallowed history as an emancipatory mecca for generations of African Americans from the Deep South. Insofar as the escape from the South was driven by the promise (or mirage) of economic opportunity, one could think of this odyssey as a “Black Wall Street Journey”: a quest for Black America’s own spin on the gospel of wealth. In a sense, Lowe’s “notes” on the Great Migration double as musings and meditations on the distance traveled on this particular “Black Wall Street Journey” thus far.

11 Boris Groys, “The Loneliness of the Project,” New York Magazine of Contemporary Art and Theory 1, no. 1 (2002).

12 Ibid.

Artwork © Rick Lowe Studio

Photos: Thomas DuBrock

Dieter Roelstraete is the curator for the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society at the University of Chicago, where he has organized exhibitions on Gelitin, Rick Lowe, Pope.L, Martha Rosler, and, most recently, Christopher Williams. Photo: Richard Pilnik

Jon Copes asks, What can Black History Month mean in the year 2024? He looks to a selection of scholars and artists for the answer.

Join Gagosian for a conversation between Rick Lowe and his longtime friends Tom Finkelpearl, author and former commissioner of the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and Eugenie Tsai, senior curator of contemporary art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, inside Lowe’s exhibition Meditations on Social Sculpture, at Gagosian, New York. The trio discusses their shared interest in transforming social structures and the evolution of Lowe’s new paintings from his ongoing community projects.

Rick Lowe and Sir David Adjaye join Thelma Golden, director and chief curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, for a conversation on the occasion of the exhibition Social Works at Gagosian, New York. The trio explore Adjaye and Lowe’s shared interests in architecture, community building, and the relationship between space and the Black body.

Join Rick Lowe in his Houston studio as he speaks about his recent paintings, describing their connections to his long engagement with the activity of dominoes and to his community-based projects created in the tradition of social sculpture.

Rick Lowe and Walter Hood speak about Black space, the built environment, and history as a footing for moving forward as part of “Social Works,” a supplement guest edited by Antwaun Sargent for the Summer 2021 issue of the Quarterly.

The Summer 2021 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Carrie Mae Weems’s The Louvre (2006) on its cover.

David Cronenberg’s film The Shrouds made its debut at the 77th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in France. Film writer Miriam Bale reports on the motifs and questions that make up this latest addition to the auteur’s singular body of work.

The mind behind some of the most legendary pop stars of the 1980s and ’90s, including Grace Jones, Pet Shop Boys, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Yes, and the Buggles, produced one of the music industry’s most unexpected and enjoyable recent memoirs: Trevor Horn: Adventures in Modern Recording. From ABC to ZTT. Young Kim reports on the elements that make the book, and Horn’s life, such a treasure to engage with.

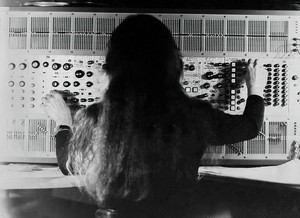

Louise Gray on the life and work of Éliane Radigue, pioneering electronic musician, composer, and initiator of the monumental OCCAM series.

Tracing the history of white noise, from the 1970s to the present day, from the synthesized origins of Chicago house to the AI-powered software of the future.

Ariana Reines caught a plane to Barcelona earlier this year to see A Sea of Music 1492–1880, a concert conducted by the Spanish viola da gambist Jordi Savall. Here, she meditates on the power of this musical pilgrimage and the humanity of Savall’s work in the dissemination of early music.

Dan Fox travels into the crypts of his mind, tracking his experiences with goth music in an attempt to understand the genre’s enduring cultural influence and resonance.