Jon Copes is a new media artist, thinker, and DJ from Raleigh, North Carolina, currently based in Brooklyn, New York. His work is heavily influenced by meme, viral image, and shared (cyber)culture, exploring questions of physical connectedness, digital community, and identity construction in the internet age.

As a new year begins and Black History Month comes to a close, I have found myself grappling with expectations of me first as a Black American, and second as someone professionally entangled in diversity, equity, and inclusion. On the one hand, I see Black History Month1 as an opportunity to dig into the vibrant and complex cultural history of Black Americans—predating the formation of the United States as we understand it today and in conversation with a broader global diaspora, dispersed after the colonization of continental Africa. On the other hand, it becomes easy to slip into a view of February as a time to regurgitate the same quotes from mid-20th-century civil rights leaders and check the box on one of the few times a year we dedicate to the ongoing histories of marginalized people in the United States. As I began to make choices about the voices and relevant media to share this month, the weighing and balancing of these viewpoints made way for clearer questions to emerge: How has the past resulted in my (and our) present circumstance, and more importantly, where does it point us as we move into the future?

Perhaps it is the state of things, both on a personal level (as I prepare a thesis, finish grad school, begin a “career,” and establish myself as an artist/person in their mid-20s) and in a broader sense (read: impending climate disaster, an election year, political unrest on a global scale), that leads me to the question, Where do we go from here? And perhaps it is the academic in me that immediately turns to find someone a bit more qualified to help piece together an answer. In this case, I have looked to North American Studies scholar José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia, in which they present the idea of “futurity”: a future-oriented outlook that is “attentive to the past for the purposes of critiquing the present” and “thinking beyond the moment and against static [history]” in an effort to “dream and enact new and better . . . ways of being in the world.”

I see art as fertile space for Black futurity, in particular in the work of Rick Lowe, Lauren Halsey, and Titus Kaphar.

Through a Futurist Lens

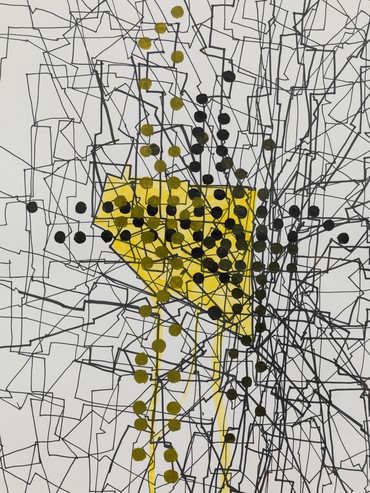

Rick Lowe’s paintings, drawings, installations, and collaborative “social sculpture” projects stem from an understanding of “the everyday” as a powerful force. For example, his domino-inspired works on canvas and paper relate a pastime spanning cultures and centuries to the present and, in my view, map out new ways of relating to the communities around us.

Lowe’s journals and sketchbooks offer page after page of drawings and scoreboards memorializing games of dominoes played by the artist. Flipping through these, I see them as an archive of personal history and connection with those around Lowe, their names scrawled in the margins with tallies keeping score, phone numbers, snippets of conversation, and notes to remember for future days. It’s this archive that has resulted in Lowe’s large-scale paintings inspired by aerial views of domino games. Wandering lines and geometric mark-making become almost topographic, like pathways coming forward on atmospheric backgrounds of deep reds, greens, blues, and yellows, or set on stark blacks, whites, and neutrals that confuse positive and negative space. Some marks sprawl across the canvas in fine white lines, like the hastily written pencil notes in the margins of Lowe’s journals. Others stand decisively on their backgrounds, in black or red, like tally marks made in wide Magic Markers.

The cartographic quality of these works brings to mind the mythologies of enslaved people braiding escape routes into cornrow hairstyles and sewing quilts with instructions toward a future of freedom. The way Lowe translates everyday practices into a visual language stands in conversation with works by the likes of David Hammons and Howardena Pindell. I also find a powerful suggestion in the idea of fun and leisure, in this case a game of dominoes between friends, as a focus on the joys rather than atrocities of Black life. In this sense, the work enters a dialogue with projects like Navild Acosta and Sosa’s Black Power Naps, presented at the Museum of Modern Art in 2023, or Jacolby Satterwhite’s dreamworld-to-come A Metta Prayer, shown in the Great Hall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2023–24.

Embedded in paintings derived from an archive of passing games of dominoes is a history of people, places, and experiences, and a gesture toward the social politics that lead to a collective future. The civil rights movement utilized the power of the everyday, in the form of sit-ins, free breakfast programs, and religious gatherings, to effect tangible change in the lives of all Americans. Thinking beyond geometric abstract painting, Lowe’s work presents a philosophy of value for the everyday and the connections we make with each other that can be applied both in our readings of Black history this month, and in the ways we might bring about a brighter future.

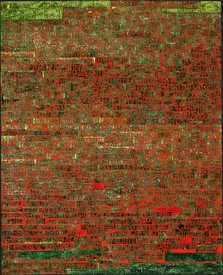

Lauren Halsey creates iconographically rich architectural installations and collages that spark conversations across time—from ancient Egypt to utopian Black futures. Much like Lowe’s, her work is deeply connected to the quotidian experiences of the people from her neighborhood, and serves as an archive of text and language from her community.

Halsey’s collage work is packed with unabashedly Black figures and cultural references. Black men, women, and children take prominence on the page, their heads adorned with artfully styled curls, intricate braids, wavy brush cuts, durags, and gravity-defying afros. They sit alongside recognizable Black figures, from politicians to athletes and celebrities, holding the same power and presence. Images of palm trees, flowing water, and the cosmos contrast views of pyramids and other ancient manmade structures. Text sampled from neighborhood tags, flyers, and signs asserts a narrative of Black pride and power. Halsey translates her collage practice from 2D to 3D in her architectural installations, which make a direct reference to the architecture of ancient Egypt. Panels of wood and gypsum are hand carved with hieroglyphic figures and powerful phrases like “Black Is Beautiful,” “Solidarity,” and “Build Autonomy.” The human scale of the installations brings these monuments of contemporary Black culture to life. The relationship between architectural forms and history finds a resonance in the multidisciplinary practices of Torkwase Dyson and Charisse Pearlina Weston.

The “sampling” and references to a philosophy of funk in Halsey’s practice mirror the contributions of Black artists to the musical history of the United States. From African vocal traditions of call and response, to Black jazz musicians of the 1920s and 1930s, to the emergence of club deejaying and hip hop in the 1970s and 1980s, Black music has a long tradition of using borrowed rhythms and melodies to express new ways of making and experiencing music. Halsey taps into this way of thinking by recontextualizing imagery to fashion new works.

Halsey’s use of archival and maximal imagery requires viewers to spend time with the history of a people and a place. She honors the cultural output and heritage of her community and highlights often overlooked histories. By engaging with ideas of home and employing tactics from across Black history as a whole, Halsey’s work embodies the many possibilities of the future of Black art.

In his paintings, sculptures, films, and installations, Titus Kaphar deconstructs notions of the “past” to recognize its influence on the present. He expresses concerns about the current social and political conditions through form and material to reveal truths about the ongoing struggle toward Black liberation.

Kaphar’s works on canvas and wood panel utilize a rich, emotional color palette that highlights absences and intrusions: cut-out figures of women and children, folds in the canvas, or thick white brush strokes that obscure some figures and reveal others. The scenes in these works borrow from Western European art traditions. They pose Black people as prominent figures, subverting expected narratives of power and history. Black mothers push empty strollers and hold the blank forms of children who have been cut out of the paintings. Black faces are imposed onto or under religious iconography. Black characters emerge behind folded and crumpled canvas portraits of white men. They gaze through the cut-out forms of human figures, meeting the eyes of the viewer.

A resistance to the notion of static history and the assertion of Black people in unexpected positions of prominence or power create a conversation between Kaphar and other Black figurative painters like Kehinde Wiley. Kaphar’s insistence on a closer viewing of both artwork and history, and of who is present and who is not, aligns with works like Kara Walker’s cutout installations. By creating a practice that emphasizes the relationship between violent colonial history and present-day systems of oppression, Kaphar’s work asks an ever-important question: Can we forge a way forward without a comprehensive understanding of how we got here in the first place?

Uncovering the complexities of untold histories and perspectives is at the center of the origins of Black History Month. The question of where we go from here remains unanswered, but the work of Kaphar, Halsey, and Lowe, all situated within the larger canon of Black history, offers a starting place and maps infinite possible trajectories. Through their work, these artists enact futures where structures of violence and oppression are dismantled and community and care are centered; where there is harmony with nature; and where leisure, pleasure, and culture are celebrated and wielded as tools for building a better future for us all.

1Black History Month grew from the week created by scholar Carter G. Woodson in 1926.