Sydney Stutterheim, PhD, is an art historian and writer whose research focuses on postwar and contemporary art. She joined Gagosian in 2018. Photo: Graham Tolbert

One of the most iconic images of performance artist and sculptor Chris Burden’s Topanga Canyon studio is a photograph taken at dusk in 2005. The warehouse-like building is aglow, its external surface taking on the mauve hue of the sky, yet the primary source of illumination comes from an unlikely source: an extensive array of antique streetlamps—painted a uniform gray and rewired to emit a cool bright light—is arranged in rows around the structure’s perimeter. In this configuration the lampposts serve as both visual signage for the studio and a protective blockade. Yet questions remain: what are these objects, and how do they relate to Burden’s practice?

In December 2000, while perusing wares at the iconic Rose Bowl Flea Market in Pasadena, Burden came across a vendor selling two antique streetlamps from the 1920s, each broken down into a complete set of parts. Burden, ever the collector, quickly immersed himself in the history of ornamental street lighting, which became a nationwide phenomenon in the 1920s and ’30s. As in many cities, the proliferation of decorated streetlamps in Los Angeles became increasingly specialized and specific to local neighborhoods. These regional variations in ornamental design made the lamps serve not only the functional purpose of providing visibility at night but also a symbolic one, marking a particular community and giving character and respectability to the burgeoning residential areas of American suburbia. Over time, Burden established a relationship with the dealer and eventually purchased his entire collection.

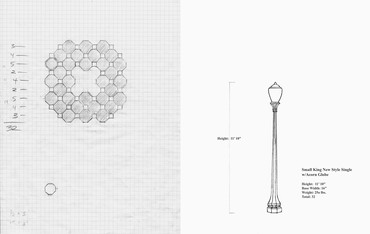

Once the lamps were in Burden’s possession, he began the process of sandblasting and coating them and replacing their hardware, updating them to use high-performance bulbs. After exploring these materials in a series of outdoor installations, he exhibited a unique iteration titled Buddha’s Fingers (2014–15). One of his last works before his passing in 2015, this sculpture comprises thirty-two cast-iron streetlamps arranged in a honeycomb formation and set on a two-inch steel base. Where visitors could weave in and out of the earlier installations, this arrangement of twelve-foot lampposts is grouped tightly enough to be impenetrable.

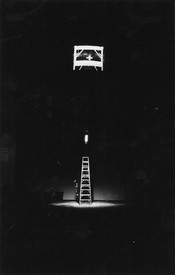

The title Buddha’s Fingers refers to the Asian citrus fruit known as Buddha’s hand, whose shape is a cluster of elongated digitlike segments. Indigenous to the Himalayas, the fruit symbolizes happiness, longevity, and good fortune and is traditionally used as a temple offering in China and as a New Year’s gift in Japan.1 The reference to temples may have its most striking analogue in Urban Light (2008), in which Burden installed over 200 of his cast-iron streetlamps, of sixteen varying heights and styles, in the open-air plaza, designed by the architect Renzo Piano, at the entrance to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).2 Referencing the neoclassical architecture often found in governmental and institutional buildings, Burden arranged the fluted lampposts into a series of pathways for visitors to navigate on foot, approaching a contemporary temple of art as if through the colonnades that led to the religious structures of ancient Greece and Rome. He positioned the tallest streetlamps at the center of the sculptural composition and the shortest at the outer edges, so that when the work is viewed from a distance, the radiant bulbs create an abstracted triangular pediment of light, underscoring the reference to a classical temple facade.3

Buddha’s Fingers extends key ideas of the streetlamp series while also departing from it in important ways. Unlike many of his earlier installations, this work was conceived as an indoor sculpture and is not site-specific. While the “Small New King” streetlamps included in Buddha’s Fingers were sourced from various residential communities in Los Angeles, other works, such as his 2012 project Holmby Hills Light Folly, contain antique lampposts taken from a certain neighborhood, in this case the affluent Holmby Hills. Historically these lampposts signaled the aspirations attached to prestige real estate sites in the 1930s, following the Great Depression, yet in Burden’s contemporary context they provide a dark and knowing commentary on real estate speculation, social stratification, and technological obsolescence. The title also recalls phenomena of the American entertainment industry such as the Ziegfeld Follies, while the glow of the lampposts accentuates the local movie-industry nickname “Tinseltown,” where movie stars’ names appear in glittering lights.

Of course, the interest in light in this particular regional context has art-historical references as well. In the early twentieth century, the California Impressionists used the techniques of French Impressionism to capture the fleeting effects of light in their immediate setting. In the 1960s and ’70s, West Coast artists such as Robert Irwin, Larry Bell, and Doug Wheeler began using light as the primary medium to create immersive environments or objects that challenged the viewer’s perceptual experience.4 Burden studied with Irwin as an MFA student at UC Irvine, and throughout his career he sustained an attraction to manipulating limits and testing visibility.

Buddha’s Fingers is uniquely compact in its composition; most of Burden’s streetlamp projects included architectural elements and explored issues of public space, civic life, and social representation. Light of Reason (2014) and Meet in the Middle (2012/2016), for example, are site-specific works created to help universities develop spaces for congregation by incorporating forms of seating alongside the streetlamps. For Meet in the Middle, Burden positioned eight streetlamps at the perimeter of two concentric circles of benches. The rings are oriented in opposite directions: the inner benches face each other while the outer benches are turned toward the surrounding environment. The divergent model of community suggested here can be seen as a subtle commentary on the top-down ambitions for these institutional spaces as sites of critical discourse, while still embracing the potential of art to generate new social relations.

Returning to the photograph of Burden’s studio and the question of the streetlamps, it is evident that these objects, found in a state of disuse, interested Burden through their possibilities. To him, these ornamental lampposts were an outmoded form of public art from a bygone era, objects often unnoticed in their banality yet critical to the effective functioning of a city. Yet he transformed them into something more: whether clustered around the studio high in the Topanga mountains or reimagined in various sculptural iterations across the globe, Burden’s streetlamp installations serve as a kind of beacon, blazing long into the future. And what better symbol of Los Angeles than light—whether the California sunshine, the twinkling urban sprawl of the city at night, or the glimpse of headlights in a rearview mirror.

2008

Urban Light

Urban Light is a permanent, large-scale installation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art consisting of 202 cast-iron streetlamps made in the 1920s and collected from Los Angeles and its many adjacent cities. Streetlamps are one of the key elements to a safe and industrialized city, according to the artist, who stated, “The richly detailed fluted lamps are an ornate totem to industrialism and represent a form of public art.” By placing the lamps so close together, Burden took it one step further to say, “The viewer’s experience of traversing through these tightly spaced fluted columns is an exalted one that recalls the marvel of seeing and walking through classic Greek and Roman architecture or a European cathedral.”

2012

Holmby Hills Light Folly

“Holmby Hills Light Folly consists of four intricate cast iron benches and four very rare cast iron lamps from the 1920s that have been fully restored. The lamps are originally from Holmby Hills, an exclusive enclave within the city of Beverly Hills. The Holmby Hills lamps are unique in that the lanterns hang from a curly crook, evoking a fairy lantern. The four lamps are placed in the four corners of a 14 × 14 foot square, with the benches placed between them, creating a quiet place to sit and reflect.”

— Chris Burden

2014

Light of Reason

Light of Reason draws directly from the location in which it resides. Inspired by the three torches, three hills, and three Hebrew letters in the Brandeis University seal, the work’s title borrows from a well-known quote by the university’s namesake, Supreme Court Justice Louis Dembitz Brandeis: “If we would guide by the light of reason, we must let our minds be bold.” Twenty-four antique Victorian-era lampposts are lined up in three rows with concrete benches poured around their bases. The three rows form three branches that fan out from the Rose Art Museum’s entrance, thus serving not only as a place to gather, but also as a gateway that leads visitors into the museum.

2014–15

Buddha’s Fingers

“Buddha’s Fingers is a sculpture consisting of a dense cluster of thirty-two antique solid cast iron streetlamps. The lamps have a hexagonal base, which lends itself to a tight honeycomb formation. The “Small New King” streetlamps were formerly used in the residential neighborhoods in Los Angeles, in the 1920s. Their height, with the globe, is just short of 12 feet.

Buddha’s Fingers was conceived and realized to be an indoor sculpture. A steel base of approximately 2 inches in height [was] fabricated and all thirty-two lamps [are] attached to this base. The lamps [are] electrified using state-of-the-art LED technology. The LED’s provide an intense cluster of cool, bright light.

The sculpture Buddha’s Fingers references both the citrus fruit and the closed hand of Buddha signifying enlightenment.”

— Chris Burden

2012/2016

Meet in the Middle

Meet in the Middle consists of eight streetlamps and twenty-four benches arranged in two circles. In contrast to Holmby Hills Light Folly, Meet in the Middle is made up of lamps and benches that face outward not only toward the college’s campus but also inward toward the center of the work. In this regard, the sculpture lends itself to be a meeting place, a social setting where students and faculty can gather and interact with the sculpture and each other. Burden conceived of the work in 2012 and it was unveiled posthumously in 2016.

1The title also connects to California agriculture, which produces the fruit. It is harvested during the winter months in the Los Angeles region.

2As LACMA director Michael Govan has pointed out, Urban Light quickly came to serve as the signature feature of the museum, marking a departure from many iconic museums around the globe in which the institution’s architecture, rather than a work of art, acts as its visual symbol.

3In a nod to the local environment, the rows of streetlamps both recall the signature palm trees flanking the Southern California roadways and draw attention to the lamps as often overlooked pillars of the urban transit system of Los Angeles.

4Robert Irwin, Larry Bell, and Doug Wheeler are often described as key figures in the Light and Space movement, characterized as a loose affiliation of Southern Californian artists who developed a regional offshoot of 1960s Minimalism focused on light and perception. In 1971, the UCLA University Art Gallery exhibited works by many of these artists in the group show Transparency, Reflection, Light, Space.

Artwork © 2017 Chris Burden/licensed by The Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY