Sydney Stutterheim, PhD, is an art historian and writer whose research focuses on postwar and contemporary art. She joined Gagosian in 2018. Photo: Graham Tolbert

On December 14, 1977, the American artist Chris Burden embarked on an approximately six-month-long relationship that would be characterized by a dysfunctional cycle of desire, adventure, instability, and eventual remorse. What began as an angry rebound following a breakup with his girlfriend and frustration with his New York art dealer became an obsession that would result in accusations of stolen property, a hit-and-run accident, and insurance claims involving the Los Angeles Police Department and California Highway Patrol.

However, the object of Burden’s fixation was not a person, but a thing: a 16,000-pound 1952 Ford tractor-trailer that he nicknamed “BIG JOB.” He would later recall of the vehicle: “It was a bad truck and I wanted it.”

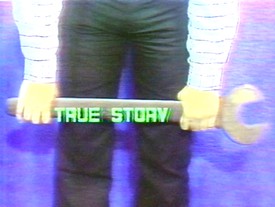

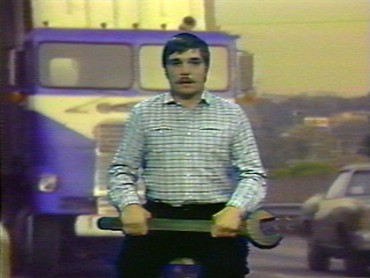

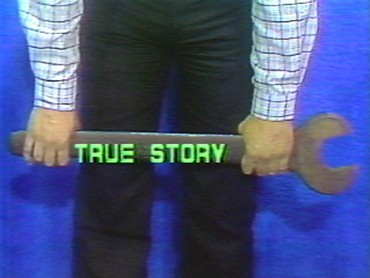

Chris Burden, Big Wrench, 1980 (still), single-channel video, color, sound, 15:12 minutes

Burden first laid eyes on BIG JOB on the side of Lincoln Boulevard in Venice, California, where it had been parked with a “For Sale” sign in the window. He imagined a range of possible projects that would afford him distance from the art world, such as using the truck to transport antiques across the country or installing a transmitter and satellite dish so it could operate as a moving communications center. Yet shortly after making the purchase, Burden began experiencing complications with his acquisition. Not only was he lacking the necessary credentials to operate the vehicle, but the truck itself revealed myriad mechanical and logistical problems. It quickly became more of a liability than an asset. Even after Burden sold BIG JOB, the authorities mistakenly came after him—instead of the truck’s subsequent owner—for fleeing the scene of a crash, and for a mismatched registration and serial number, indicating that the vehicle was stolen. Ultimately, Burden realized that BIG JOB was more than he could handle, noting, “I felt that I had become guilty by association and that ‘BIG JOB’ possessed a curse which I could not get rid of.”1

Chris Burden, Big Wrench, 1980 (still), single-channel video, color, sound, 15:12 minutes

Finding this unexpected turn of events compelling, Burden wrote a short story titled “The Curse of Big Job,” which he published with accompanying photographs in the March 1979 issue of the art quarterly High Performance. In fact, Burden treated the entire ordeal as a piece of performance art, for which he was best known at the time. He had first gained notoriety in 1971 for Shoot, his now-seminal performance in which an acquaintance-turned-marksman shot a rifle toward Burden’s arm. The intention was for the bullet merely to graze his skin, but the gunman miscalculated and the bullet went into the artist’s arm.

Press and news outlets across the country became fascinated with Burden’s radical reimagining of the definition and parameters of what constitutes a work of art. Like his contemporaries Marina Abramović, Vito Acconci, Valie Export, Joan Jonas, and Hannah Wilke, Burden pioneered a new approach to art making that often used the artist’s own body as both subject and object, erasing the conventional distinction between artist and artwork. Expanding upon the phenomenological or bodily involvement of the viewer that was invoked by Minimalist sculpture of the mid- to late 1960s, performance artists working in the following decade developed forms of art that tested concepts of presence, duration, endurance, and artist-audience relations. The development of the relatively affordable Sony Portapak recorder opened the way for artists to use video both as a means of documenting these ephemeral performance-based works and as a medium for art in itself.

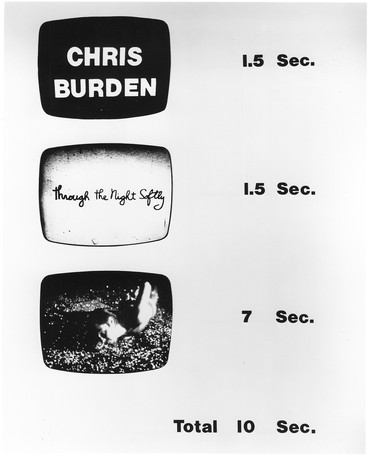

Chris Burden, TV Ad, November 5–December 2, 1973

On November 5, 1979, San Francisco’s KTSF television station broadcast a video by Burden titled Big Wrench. Approximately fifteen minutes long and produced specifically for television, the work would have taken viewers by surprise with its dramatic shift in content. After a short set of opening title frames, Burden abruptly appeared on-screen—seated, facing the audience, and holding a large wrench in his lap with both hands. As he spoke to the camera, video footage of various trucks driving around the Los Angeles area played behind him, thanks to early green-screen technology, which was often used for news broadcasts at the time. Burden directed his autobiographical monologue, adapted from “The Curse of Big Job,” to the home audience, chronicling how he began seeing BIG JOB around his neighborhood and “fell in love with it.”

Issued as an independent video the following year, Big Wrench occupies an important position within Burden’s broader artistic production. The work’s personalized narrative—in which Burden recounts his anger and sadistic fantasies, as well as his recreational drug use—and the artist’s repeated declarations of the veracity of his claims reflect a confessional mode of performance and video art that was prevalent in his earlier projects. Burden’s interest in motor vehicles had also been a recurring feature of his career, and was notably developed in large-format kinetic sculptures such as The Big Wheel (1979), in which the energy from a revved motorcycle was used to spin an enormous cast-iron flywheel.2 Moreover, Burden had previously produced multiple projects that exploited the medium of television. Whether overtaking a live broadcast (TV Hijack, 1972) or purchasing advertising spots in which he aired subversive video works that interrupted typical commercial programming (TV Ad, 1973; Poem for L.A., 1975; and Chris Burden Promo, 1976), Burden used television as a conduit for challenging mass media, turning the communicative and manipulative aspects of the medium against itself.

Chris Burden, The Big Wheel, 1979, cast-iron flywheel powered by a 1968 Benelli 250 cc motorcycle, 9 feet 4 inches × 14 feet 7 inches × 11 feet 11 inches (284.5 × 444.5 × 363.2 cm)

Chris Burden, TV Hijack, February 9, 1972, performance, Channel 3 Cablevision, Irvine, California. Photo: G. Beydler

According to Burden, sometime after he sold BIG JOB, an art collector read his account of the events and contacted the artist about purchasing the truck for his personal collection. Burden attempted to reach out to the new owner to buy it back, but his efforts were thwarted. As with a former romantic partner whose presence has left an irreparable impression, Burden could not seem to escape the object of his affections. As he ruefully declares in the final moments of Big Wrench: “I had finally gotten rid of BIG JOB and now I wanted it back.”

1Chris Burden, “The Curse of Big Job,” High Performance 2, no. 1 (March 1979), p. 3.

2Chris Burden on The Big Wheel (1979): “The Big Wheel consists of an 8 foot diameter, 6,000 pound, cast-iron flywheel mounted in a vertical position on a wooden support structure of 6 by 6 inch timbers. The axle of the large wheel is supported by two low friction bearings. A motorcycle is positioned so that it can be rocked backwards, making firm contact between its rear tire and the iron wheel. The motorcycle is then ‘driven’ through its gears until its maximum speed is reached. The motorcycle is then pulled away, leaving the large wheel spinning silently at about two hundred r.p.m. Because of the enormous amount of kinetic energy stored in the wheel, it continues to spin for about two and a half hours before coming to a rest.”

This article was produced on the occasion of a free public screening of Big Wrench at Gagosian, Britannia Street, London, on January 18, 2019, in partnership with MUBI.

All images © 2019 Chris Burden/Licensed by the Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York