Brice Marden

Larry Gagosian celebrates the unmatched life and legacy of Brice Marden.

November 6, 2017

At the Royal Academy of Arts in London, Brice Marden sat down with fellow painter Gary Hume and the Royal Academy’s artistic director, Tim Marlow, to discuss his newest body of work. The conversation evolves into a rich investigation on the medium of painting more generally, from the centrality of light to the complexities and sublimity of the square.

Brice Marden in his studio, Tivoli, New York, June 2017. Photo: Eric Piasecki

Brice Marden in his studio, Tivoli, New York, June 2017. Photo: Eric Piasecki

Tim MarlowBrice, when did you first realize that you wanted to be a painter?

Brice MardenIn the second half of my senior year of high school. I had always wanted to go into the hotel business, so I went around to look at hotel schools, but soon realized that was not for me. Then I had taken to cutting school, hitchhiking into the city, and going to museums. I would do a museum and a Brigitte Bardot movie and then try to avoid getting on the same train as my father going home. It was fun.

TMWhen did you sort of feel that you had your own voice or vision as a painter?

BMI think at Yale. I had a great teacher, they were all great, but Esteban Vicente said, “You have just really painted yourself into a corner and it looks like you’re having a good time with it.”

TMGary, what about you?

Gary HumeI started to become a painter because I couldn’t do much else. The thing that fascinated me was the amount of problems. There are just so many problems and they’re all solvable. And they’re solvable with no proof. Of course you start off terrible. I was completely useless but I was quite bold, so I didn’t mind making terrible mistakes. In fact I quite enjoyed making the worst things possible, it gave me the freedom to make something else, to not compete, to be the worst in the class. The problems are just fascinating, trying to move around a rectangle.

All I can say is there’s nothing without light. Painting a painting in Greece and trying to paint that same painting in another light, it doesn’t work.

Brice Marden

TMAre you better at solving problems now than you were 20 years ago?

GHNo, because you have to create a new problem to stay interested. It’s very boring to repeat a painting that you’ve already made. When you’re young, you’re avoiding everybody else’s voice because it’s absolutely pointless making somebody else’s painting. When I was a student I absolutely loved Brice’s paintings. I’d want to make them but it was totally pointless, because he made them. In the beginning I had only seen his paintings as reproductions, so I always thought that they were immaculate. Then I went to the Tate and had a look at one. I looked at the edge and I might be wrong, but it felt like there was a cigarette butt stuck to the side, still in paint. And I was like, “Oh my God, this is brilliant. He actually makes these things.” And it gave me a huge push to get back into the studio and start to use paint.

TMBrice, was there a cigarette butt there?

BMNo. [Laughter] Classic. But that really is the point when you realize that you’re making things that didn’t exist before and putting them out into the world. That’s the moment when you feel like you’re a painter or whatever, that’s it.

TMDoes the anxiety of influence go away as you get older? What Gary’s articulated is a fear that a lot of young creative people have which is a reverence for the past, but also there’s the anxiety about being seen as too derivative. Does that get easier?

BMI don’t know. I don’t worry about it. There are some artists that just really interest me and I look at them more carefully than ones I’m not as interested in.

Installation view, Brice Marden, Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill, London, October 4–December 22, 2017. Photo: Mike Bruce

TMI was struck in your present show by the relationship to history, but in a carefully considered way, and there are fortuitous connections. Paul Hills, who has written the essay for the upcoming catalogue, works out that in your recent paintings, there is a strip at the bottom and that is where your process is revealed. In that strip there’s the veil of the first coating of terre verte paint, but there’s also a recording of the process, the splashes that fell as you applied more layers to the top of the canvas. But Hills says that the proportion of that strip at the bottom is the same as a predella on a Renaissance altarpiece. I’m not asking if that was conscious or not, but I quite like the connection.

BMYes I really liked his read of the paintings. I was much more interested in the square, it’s a 6 by 6 foot square. I had always avoided the square because I thought it was too perfect, you know. Plus, being at Yale with all this Albers stuff, I mean, they didn’t teach you Albers, but it pervaded. So I avoided it. And then a couple of years ago, it just started, and kept, coming up. I had these 6 by 8 foot canvases and one day I just flipped one to be vertical and I liked it, so I’ve continued working with it.

TMIt’s interesting, that shift in format, because in your work, that rectangular format has been almost all pervasive, now there’s a shift. Whereas you, Gary, have worked in different formats continuously throughout your career.

GHI’ve tried to avoid a square. But I feel completely different about a square than Brice. I think a square is a complete nightmare because I can’t get any tension in it. Brice doesn’t like an image. And I absolutely like an image. I want to make a picture that is a thing that you lose yourself in but it’s always a picture. And Brice is trying to get rid of the picture. And so a square for Brice might be a completely fantastic place, but for me it’s a complete nightmare because I want there to be anxiety between that area and that area.

TMBrice, in this new series there is a significant shift in the sense that it started with a conceptual idea. There’s a framework that you’ve given yourself: there will be ten canvases and you’re going to explore ten different industrial types of terre verte pigment. Once you established that, was it the same process for you or did you just go through the steps of putting a set number of layers on each?

And as I painted them, number one, you work through a kind of physical thing, each one of them is different physically, due to the paint. And then you kind of get used to that, but then it starts changing. It became much more of an organic thing as I worked on them.

Brice Marden

BMNo, when it started out, well, you could have hired it out. “This one’s going to be this.” My concern was that the more layers there were, the more I painted on them, the blacker they would get. And as I painted them, number one, you work through a kind of physical thing, each one of them is different physically, due to the paint. And then you kind of get used to that, but then it starts changing. It became much more of an organic thing as I worked on them. So it wasn’t a matter of doing ten layers, it was a matter of finishing the painting. So some had ten layers, some had twelve layers. They involved the act of painting.

GHIt’s seems to me that it’s not a conceptual work. A conceptualist would have gone, “There’s ten layers and here’s what it looks like.” But you’re not a conceptual artist; you might have used it as a start—

BMYes, it started with, “Well, I’ve got these ten things, it’ll be this.” And then as I worked on them it became much more, it got further and further away from that, and it became much freer.

TMWhat surprised you about that journey or that process? Did the paintings have a connection to how you thought they would emerge or were you totally surprised as you worked through each of the ten paintings?

BMThese paintings came much faster than my paintings usually do. There was this kind of freedom. And so here I am working on the most constricted thing and it feels unbelievably free. And I was a bit surprised that it turned out as well as it did, in that it did change from the initial concept. And I spent a lot of time just sitting and looking at them, trying to figure it out.

TMWatching paint dry. [Laughter]

BMWell.

TMI am fascinated by—and it probably won’t surprise either of you—how different ten different kinds of paint that purports to be the same pigment from a kind of clay-based iron silicate, just how fundamentally different the stuff is in each one. I suppose that’s a non-painter’s response isn’t it, because paint is different. Except for you, Gary, the household paint, the gloss paint that you use, there’s a kind of freshness that is there in the can and is there on the surface. Is the shift surprising for you?

GHWell, as you could have guessed, I’m not as interested in the different brands of paint having different colors because Brice could have mixed all those colors—

TMAnd he might have done.

GHBut I always feel that Brice’s paintings are from nature. Like they’re actual nature—the actual world comes out of Brice’s paintings—and oil paint is perfect for that. Oil paint is made from nature, the pigments have all come from the ground. Whereas my paint is purely industrial. All of its colors, none of them actually come from the earth. They all come from chemical compounds. Rather than being from nature, it’s what we do to nature. So my paint is more like the world we live in rather than the world that we’re of. And it’s a paradox of my love of Brice’s paintings. I used to project my paintings onto white grounds, that projection allowed me to feel the image arriving like a movie. I then changed that. I got fed up with the quickness of that, so rather than capturing something, I wanted to grow the painting. I changed the ground from white to brown. That changed my mindset about how a painting develops. So rather than the painting arriving on it, I wanted the painting to grow out of it. And if you look at Brice’s paintings, Brice’s paintings always grow from the surface. You never feel like he’s—even though everything’s incredibly physical, it’s all put on and put on, you kind of feel like they’re sort of slowly coming toward you, as if it’s an actual growth. Now my paintings don’t really look like that, but that’s how it feels making them, just by doing a very simple thing like changing the color of the ground.

And if you look at Brice’s paintings, Brice’s paintings always grow from the surface. You never feel like he’s—even though everything’s incredibly physical, it’s all put on and put on, you kind of feel like they’re sort of slowly coming toward you, as if it’s an actual growth.

Gary Hume

TMBrice’s paintings, particularly the new series, are also very immersive, aren’t they? They overwhelm. Whereas yours repel—

BMWhat I love about Gary’s paintings is that they’re adventurous. And the image, the result, is part of this adventure. You’re taking it all in. It’s exciting—I don’t think about process or anything like that, it’s just what he comes up with that is incredible. And I say incredible in the sense that it’s maintaining a certain sense of adventure. That’s what I’ve always liked about it.

GHDid you hear that?

TMI did. [Laughter] You’ve got the remark now for your CV. That’s exactly right. Let’s talk about light, if we can briefly, because obviously you both work with it and harness it or explore it in different ways. Gary, in your work light is literally reflected off the surface of the aluminum, and gloss paint itself reflects quite a bit. Even with your work on paper, the surface is coated, so you get this amazing fluid or diffused light.

GHHousehold gloss paint is an incredibly beautiful material. Oil paint dries and gloss paint sets. It has a very different value. It flows. One of its properties, which is so fantastic, is that it reflects. And if you’re a painter like me who never learned the skills to be able to paint properly, to be able to take the light from the world rather than reproduce the light on canvas, it is just truly fantastic. I can get the reflections of the room.

TMBrice, how does light play as an active element when you make a painting? I know that you have different studios in different parts of the world, so beyond the different qualities of each place, how much is light something that you are trying to harness and how much is it something that becomes revealed through the process?

BMAll I can say is there’s nothing without light. Painting a painting in Greece and trying to paint that same painting in another light, it doesn’t work.

GHWhat is just truly fantastic is to take the end of day, as the light goes down, and turn the lights off in your studio. There is this unbelievable pleasure in watching everything change and then disappear. I mean, that is like heaven because you’re making all these movements and changes throughout the day and then you can relax with a cup of tea in a chair and you can actually watch the world do that to the paintings. It’s like owning them for a bit rather than working on them.

BMI totally agree with that. I mean, I’m up on the Hudson and I keep thinking, “Oh, is this when I’m going to start painting like the Hudson River School painters?” And there’s no way because I don’t paint that way and I don’t paint light. But there’s hardly anything better than just sitting there watching the light change on the paintings. Some are made to do that more in a way, like Rothko. But it’s really just one of my favorite things, doing that. But I don’t drink tea. [Laughter]

Artwork © Brice Marden/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, and DACS, London 2017. Special thanks to the Royal Academy of Arts, Brice Marden, Tim Marlow, Gary Hume, Tyler Drosdeck, Noah Dillon, and Kate Blake. To listen to the full talk, visit the Royal Academy’s website at www.royalacademy.org.uk

Larry Gagosian celebrates the unmatched life and legacy of Brice Marden.

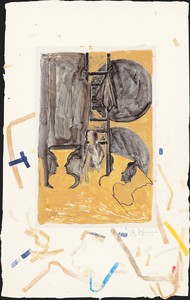

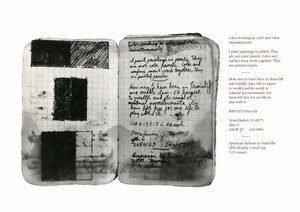

Eileen Costello explores the oft-overlooked importance of paper choice to the mediums of drawing and printmaking, from the Renaissance through the present day.

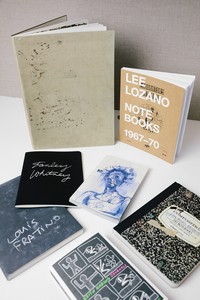

Megan N. Liberty explores artists’ engagement with notebooks and diaries, thinking through the various meanings that arise when these private ledgers become public.

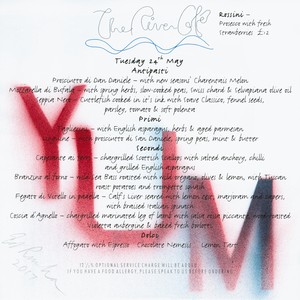

London’s River Café, a culinary mecca perched on a bend in the River Thames, celebrated its thirtieth anniversary in 2018. To celebrate this milestone and the publication of her cookbook River Café London, cofounder Ruth Rogers sat down with Derek Blasberg to discuss the famed restaurant’s allure.

Paul Goldberger tracks the evolution of Mitchell and Emily Rales’s Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Maryland. Set amid 230 acres of pristine landscape and housing a world-class collection of modern and contemporary art, this graceful complex of pavilions, designed by architects Thomas Phifer and Partners, opened to the public in the fall of 2018.

Four paintings by Brice Marden have been incorporated into a new dance commission based on T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, with choreography by Pam Tanowitz, and music by Kaija Saariaho. The performance will premiere on July 6, 2018 at the Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard as part of the SummerScape Festival. Gideon Lester, the Fisher Center’s artistic director for theater and dance, spoke with Marden about the canvases that form the set design.

In honor of Robert Pincus-Witten, we share an essay he wrote in 1991 on Brice Marden’s Grove Group.

With preparations underway for a London exhibition, we visit the artist’s studio.

Join Gagosian for a conversation between director, producer, and writer Sophia Heriveaux and actor, director, and writer Roger Guenveur Smith inside the exhibition Jean-Michel Basquiat: Made on Market Street, at Gagosian, Beverly Hills. Heriveaux and Guenveur Smith both share a personal connection to Basquiat: Heriveaux is the artist’s niece and Guenveur Smith was one of his friends and collaborators. The pair discuss Basquiat’s work and legacy, as well as his lasting impact on contemporary art and culture.

Join Brooke Holmes, professor of Classics at Princeton University, and Lissa McClure and Katarina Jerinic, executive director and collections curator, respectively, at the Woodman Family Foundation, as they discuss Francesca Woodman’s preoccupation with classical themes and archetypes, her exploration of the body as sculpture, and her engagement with allegory and metaphor in photography.

In conjunction with Marks and Whispers, at Gagosian, Rome, Oscar Murillo and Alessandro Rabottini sit down to discuss the artist’s paintings and works on paper in the exhibition, as well as how the show emphasizes the formal, political, and social dimensions of the color red in Murillo’s work of the last decade.

In this video, Gagosian presents a conversation between Jordan Wolfson and Johanna Burton, Maurice Marciano Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. The pair discuss Wolfson’s animatronic work of art Body Sculpture (2023).