Brice Marden

Larry Gagosian celebrates the unmatched life and legacy of Brice Marden.

February 12, 2018

In honor of Robert Pincus-Witten, we share an essay he wrote in 1991 on Brice Marden’s Grove Group.

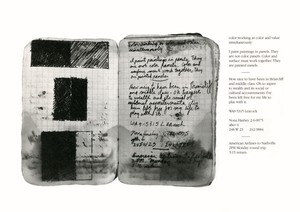

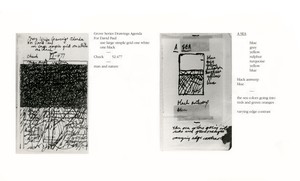

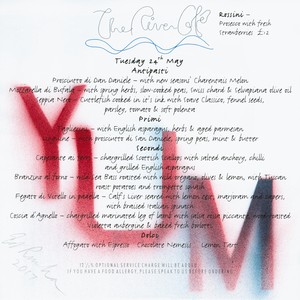

Brice Marden, The Grove Group Notebook, c. 1971

Brice Marden, The Grove Group Notebook, c. 1971

Robert Pincus-Witten worked with Gagosian for many years as a writer, curator, and collaborator. He was smart, kind, and funny, and he will be missed. In 1991, during the years he spent most immersed in our program, he wrote an essay on Brice Marden’s Grove Group series, which accompanied an exhibition of the works—the first time all five paintings had been brought together in one show. The series, which Marden began painting in 1973, inspired by his trip to Greece, has been hailed by many, including Roberta Smith, for whom its “seemingly flat monochrome fields were constantly flipping open, yielding suggestions of light and space and moody atmosphere.” It wasn’t until Marden’s 2017 exhibition at Gagosian London that monochromes took center stage in his practice once again. Pincus-Witten, as he always did, brought fresh and precise thinking to these earlier works, utilizing Marden’s notebooks from his 1971 trip to the Mediterranean to explore how the artist was able to unify abstraction with associative relations.

Long a keeper of journals, I felt certain that when Brice Marden first went to Greece in 1971 he kept some record of this consequential event, however desultory and laconic. After all, apart from any question of art, there is the simple fact that Marden and his family have returned to Greece every summer since. My intuition proved correct; twenty years later, amid the drawing pads and manila envelopes of a studio filing cabinet, a few small notebooks were found, not quite pads really, in which stray, vivid first impressions of landscape and temple site had been logged.

Owing to the powerful impression that Greece made upon the painter, several works and thematic groups by Marden can now be understood in terms of that radiant light, be the illumination explicit or coded: names, compositional structures or allusive references point to Greece as the origin. The Hydra paintings of 1972, for example, hint at the importance of his summering island, if only through name alone; by contrast, the Thira paintings of 1979–80 derive their composition from the post and lintel structure of temple architecture reduced to diagrammatic essential.

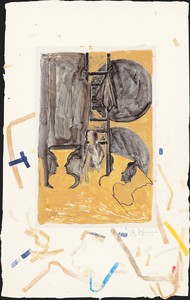

In like manner, the five large encaustic works known as The Grove Paintings refer to Greece through name as well as allusion. These paintings were immediately followed by three Grove Addenda, collages incorporating mechanically reproduced images of classical monuments, picture postcards of The Charioteer of Delphi, and the seated goddesses of the Elgin marbles; one of them presents a real olive leaf held in place by short length of transparent pressure tape. The three Addenda were followed by a suite of five gridded drawings called The Grove Group. Marden now refers to this extensive body of work—the encaustic paintings, the collages and the drawings as The Grove Group, and considers 1973 to be the date of completion for the series. The present assembly of these disparate components marks the first time that The Grove Group has ever been shown in its virtual entirety. To these must be added the Grove Group Notebook which makes its appearance with this event.

The notebooks that parallel The Grove Group are of critical importance as they record the early beliefs and statements of purpose of an artist now recognized as an incontestable master. In studying the notebooks one was able to locate specific references to The Grove Group despite the myriad of address, travel trivia, exquisite drawing, and transient aides-mémoires that comprise the bulk of these diaries. In short, from small worn daybooks another kind of conclusion was drawn, one that, for want of a better name, may be called The Grove Group Notebook though no such concentrated ambition inspired their initial transcription.

Brice Marden, The Grove Group Notebook, c. 1971

The notebooks are of modest format; black plastic covers secure squared graph paper of a European type. Made of cheap pulp, this paper rapidly dries and crumbles, virtually metastasizes owing to a high acid content. Café and bistro use this sort of paper for placemats; this is the paper that when dragged with fork or fingernail calls to mind certain off-the-cuff, torn drawings by Lucio Fontana. Of a format easily slipped into jean pockets, the journals are blurred by water stain, ringed from duty as coasters for drinks. Three of the notebooks were bought along the way, as shown by the stationery shop markings of their Greek origin.

Unlike other diaries, Marden’s entries do not retail the bon mots or brittle banter of a privileged community; nor do they ventilate an angry laundering of dirty linen. His journals are not the place of raw resentment or of scores settled. There are no prurient passages; revelations of domestic stress are absent. By contrast, the notebooks convey a shining-brow’d exhilaration, the neo-Greek zeal of the Edwardian public school. Marden’s nice sense of moral balance inflects his record as do the refined drawings to be found there—pages that, in being worn and degraded, keenly manifest the painter’s nostalgia for limpid beauty imperiled. If nothing else, Marden is the most poignantly aesthetic of all the artists who emerged under the Minimalist rubric as well as its most clandestine and patrician colorist.

To divert attention away from the editing of these spare texts, the rare misspelling is corrected in typographic copy. To exaggerate a common lapsus—“to” for “too,” say—by noting it by asterisk or “[sic]” would be ham-fisted in this context. Similarly, the common English spelling of names—“Phidias” for “Phedias,” say—are given rather than the painter’s occasionally hasty approximations. These entries focus Marden’s gaze as they force a reconsideration of the academic view of Minimalism. It is certainly noteworthy that the absence of meaning (beyond purely formal consideration) said to characterize Minimalism is hardly the case with Marden. His tree-like diagram of the tri-partite structure of the Grove Paintings—the upper zone equaling leaves and sky, the middle sector that of the trunk and the lower rectangle that of the earth—contradicts a wholly abstract reading from the very outset. Marden’s salient remark, “Art made by system makes artists artisans” aphorizes the artist’s distance from a doubtfully rudimentary reading of Minimalism.

As would be expected from the current perception of Minimalism, the privileging of formalist values over those of interpretation is capital, taken for granted. Diane Waldman, for example, noted in the catalogue of her early survey for the Guggenheim Museum (1975), that Marden’s work “is often stimulated by a postcard, a person, even a situation, but the finished product bears only a remote associative relation to its inspiration.” [p. 20]. My emphasis means only to underscore the reductivist bias of the day, one that willfully marginalized the role of associative value or imaginative power as spurs to abstraction. The Grove Group Notebook now provides a text of spirited resistance to this valorizing of form over what condescendingly used to be referred to as “literary content.” Clearly, reductive biases favoring pure form marginalize the primacy of associative values.

The notebooks that parallel “The Grove Group” are of critical importance as they record the early beliefs and statements of purpose of an artist now recognized as an incontestable master.

Robert Pincus-Witten

By contrast, when in the ’70s, a rare non-formalist interpretation was tendered, it seemed to fall far afield. Jean-Claude Lebensztejn’s observation, for example, that “…the five paintings [of Marden’s Annunciation group, 1978] are linked to the five states of the Virgin during the Annunciation, as described in a sermon by Fra Roberto Caracciolo of Lecce (fifteenth century)” seems far less outlandish than it did in 1978 in light of the evocative tissue of associations that The Grove Group Notebook reveals.

For my part, in reflecting on the resurgence of painting and its perquisites that marked the later-’70s and early ’80s, it struck me that this international appetite for painting was informed by a refreshed historicism manifested by artists whose work had earlier been warped in a distorting mirror of pure formal signification. Thus I took note of a “growing awareness of the pronounced iconographic classicism that attached itself to minimalist logic,” citing “Ellsworth Kelly’s spare balances and swells born of an acute appreciation of classical epigraphy and letter form,…Marden’s Fra Roberto Carraciolo of Lecce, Mangold’s Albertian facades, Novros’ predelle,” among many manifestations at that decade’s turn.

Once maneuvered into this path, it becomes apparent that, in a larger sense, the grove of Marden’s Grove Group participates in an elect iconography, that of the Sacred Grove Dear to the Muses. Blood fallen to earth where Perseus cut off the head of Medusa marks the place where Pegasus, symbol of poetic imagination, first appears. Hippocrene, the waters of poetic inspiration surge surface. Pegasus, beating hoofs upon the earth, cause the Springs of the Pegae to surge forth, about which the Sacred Grove takes root. Here the muses congregate, their meeting place a mouseion, origin of the place and word for the museum.

For Symbolist painting the most noteworthy Sacred Grove is the large decoration by Puvis de Chavannes for the grand stairwell of the Museum of Fine Arts in Lyons (1884), birthplace of the painter. In being situated this way, Puvis’s Sacred Grove Dear to the Muses is literally enclosed within the walls of a museum. Though perhaps a reputation in revision today after an uncertain neglect, it should not be forgotten that major artists such as Seurat, Gauguin, Matisse, Picasso and Torres-Garcia all esteemed Puvis de Chavannes highly, an admiration measurable even in direct pictorial quotation.

For all that is recondite in the myth of the Sacred Grove, its details are the common fodder of travel guide and encyclopedia; features are part and parcel of the Freudian baggage we all carry about with us, hardly Marden alone. Bullfinch’s standard mythology aside, children well into the twentieth century were raised on Hawthorne’s Tanglewood Tales, an influential retelling of the antique legends. And it was Freud who thought that the decapitation of the Gorgon, Perseus’ slaying of Medusa, was the legendary prefiguration and paradigm for the castration anxiety central to an elaboration of the Oedipus Complex.

In not a few respects then, telling comparisons between Puvis de Chavannes and Marden may also be drawn. Among these are a composition in registers; in contemporary art that stratum has become the literally flat plane of modernism—its virtual insignia—though the slow build and depth of color of Marden’s planes, it seems to me, are visually anything but “flat.” Beyond this surface aspect, a deeply researched and subtle color is one that also echoes Puvis de Chavannes; his color also once struck the viewer as oddly mannerist—the yellow/ green pond, for example, of the Bois de Boulogne that the painter transformed into Hippocrene and the Springs of the Pegae of his Sacred Grove. Such an alert use of color is maintained in the alchemy of Marden’s wary, never-seen-before palette.

We take Duchamp’s elevation of the mental above the merely retinal, an insight substantially grounded in Symbolism, as touchstone of the modern. So, in drawing a parallel between Puvis de Chavannes and Marden, there is above all petty formalities, that of a painting placed not just at the service of the senses but of the mind as well. Nothing is more revealing of this predilection than the documents, both pictorial and literary, of Marden’s Grove Group, here assembled together for the first time, muses gathered anew at a mouseion. It was this Gathering at a Spring that became talisman to the most consequential works of the early twentieth century; Nijinsky/ Stravinsky’s Sacre, Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, Matisse’s The Dance. Arguably, such is the prospect for Marden’s Grove Group as well.

All artwork © 2018 Brice Marden/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Larry Gagosian celebrates the unmatched life and legacy of Brice Marden.

Eileen Costello explores the oft-overlooked importance of paper choice to the mediums of drawing and printmaking, from the Renaissance through the present day.

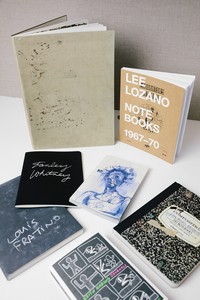

Megan N. Liberty explores artists’ engagement with notebooks and diaries, thinking through the various meanings that arise when these private ledgers become public.

London’s River Café, a culinary mecca perched on a bend in the River Thames, celebrated its thirtieth anniversary in 2018. To celebrate this milestone and the publication of her cookbook River Café London, cofounder Ruth Rogers sat down with Derek Blasberg to discuss the famed restaurant’s allure.

Paul Goldberger tracks the evolution of Mitchell and Emily Rales’s Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Maryland. Set amid 230 acres of pristine landscape and housing a world-class collection of modern and contemporary art, this graceful complex of pavilions, designed by architects Thomas Phifer and Partners, opened to the public in the fall of 2018.

Four paintings by Brice Marden have been incorporated into a new dance commission based on T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, with choreography by Pam Tanowitz, and music by Kaija Saariaho. The performance will premiere on July 6, 2018 at the Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard as part of the SummerScape Festival. Gideon Lester, the Fisher Center’s artistic director for theater and dance, spoke with Marden about the canvases that form the set design.

At the Royal Academy of Arts in London, Brice Marden sat down with fellow painter Gary Hume and the Royal Academy’s artistic director, Tim Marlow, to discuss his newest body of work.

With preparations underway for a London exhibition, we visit the artist’s studio.

David Cronenberg’s film The Shrouds made its debut at the 77th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in France. Film writer Miriam Bale reports on the motifs and questions that make up this latest addition to the auteur’s singular body of work.

Alison McDonald celebrates the life of curator Richard Marshall.

Alice Godwin and Alison McDonald explore the history of Roy Lichtenstein’s mural of 1989, contextualizing the work among the artist’s other mural projects and reaching back to its inspiration: the Bauhaus Stairway painting of 1932 by the German artist Oskar Schlemmer.

The mind behind some of the most legendary pop stars of the 1980s and ’90s, including Grace Jones, Pet Shop Boys, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Yes, and the Buggles, produced one of the music industry’s most unexpected and enjoyable recent memoirs: Trevor Horn: Adventures in Modern Recording. From ABC to ZTT. Young Kim reports on the elements that make the book, and Horn’s life, such a treasure to engage with.