Brice Marden

Larry Gagosian celebrates the unmatched life and legacy of Brice Marden.

June 6, 2018

Brice Marden speaks to Gideon Lester about his collaboration on Four Quartets, a dance commission based on T. S. Eliot’s modernist masterpiece, with choreography by Pam Tanowitz and music by Kaija Saariaho. Their conversation took place in advance of the premiere, at the Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College, where Lester is artistic director for theater and dance.

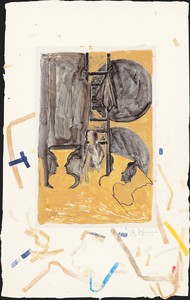

Brice Marden, Untitled (Hydra), 2018, oil on linen, 83 × 270 inches (210.8 × 685.8 cm) © 2018 Brice Marden/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Brice Marden, Untitled (Hydra), 2018, oil on linen, 83 × 270 inches (210.8 × 685.8 cm) © 2018 Brice Marden/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Gideon LesterWhen did you first encounter Four Quartets?

Brice MardenIt was probably in the late ’70s. I remember my brother had a book of Eliot’s works, and I was curious about what he was reading. I had a friend who was a restaurateur and dope dealer, who also taught English. We read the Quartets together and he explained them to me, but I wouldn’t say I’ve made a study of them.

GLI read an essay by [art critic] David Anfam in which he draws a parallel between your work and Four Quartets. He describes the “hushed stillness-in-movement quality” of your painting Ru Ware Project (2007–12), and quotes from “Burnt Norton”: “Only by the form, the pattern, / Can words or music reach / The stillness, as a Chinese jar still / Moves perpetually in its stillness.”

BMI’m glad he saw that, though I wasn’t thinking directly about Eliot when I painted it.

GLIn Four Quartets, Eliot is seeking to express an experience of the sublime. This seems to be a point of deep connection with your own work.

BMI’ve recently been doing all these green paintings, and have been working a lot with the pigment Terre Verte—green earth—and there’s so much reference inherent in these materials that I don’t think I’m putting all that much of myself into it. More and more, I find when I paint that I go sort of blank, as if I’m a vehicle. I’m at a point in my life where I’m reconsidering a lot of things, how I’m spending my time. That’s one of the reasons I took on Four Quartets.

GLWhat interested you in the project?

BMThe whole collaboration thing. I really like dance. It seemed like a very good idea, the combination of poetry, dance, contemporary music . . . though I’m not terribly involved in music right now, or dance. Also I said “yes” because you made it difficult to say “no.” It’s Bard, and I’m up here, I’m part of the community.

GLI think you’ve collaborated with choreographers twice before?

BMI did a set for a Karole Armitage production of Orpheus and Eurydice in Italy, and lights and costumes for Baryshnikov, who was performing Cunningham’s Signals.

GLYou’ve talked in the past about the way that the physical action of painting has a choreographic quality for you. Your painting The Muses (1991–93) was inspired by dance, wasn’t it?

BMThat was more about madness. I had an image of the muses dancing wildly in the Peloponnese. There’s no depiction in my paintings, though there is movement, which could be associated with dance.

GLHave there been periods when you were particularly interested in dance? I imagine you encountered postmodern choreographers when you were working as Robert Rauschenberg’s assistant?

BMI remember that Merce [Cunningham] would come by the studio. Rauschenberg worked mostly at night, so I’d be getting ready to go home and all these people would start trickling into the studio at cocktail time. He was working with Deborah Hay, Steve Paxton.

GLThe two-dimensional nature of painting—the plane—is of great importance to you. I’m curious how it has been for you to think about set design, which is three-dimensional.

BMYes, the whole idea of flatness, and the tension between flatness and the illusion of non-flatness—a lot of that is arrived at by color. But for Four Quartets most of the pieces Pam and Clifton [Taylor, the scenic designer] chose are very architectural, and they can be broken down in an architectural pattern.

Pam Tanowitz and Brice Marden in Brice’s studio in Tivoli, New York. Photo: Gideon Lester

GlThe design incorporates four of your paintings, one for each of Eliot’s poems. Maybe we could talk about each of them. The first, for “Burnt Norton,” is a detail from a painting with four sections, called Uphill 4 (2014). What’s the significance of the title?

BMNothing. I have a studio here in Tivoli that’s up the hill. I refer to it as the uphill studio. That’s all.

GLI had an elaborate theory about why the title was perfect for Eliot’s poem. He has a line about “the figure of the ten stairs,” an image from the mystical writer John of the Cross, which imagines love as a staircase. So, uphill!

BMThat’s a very rich interpretation and it’s fine by me. That’s what happens when you put things out in the world.

GLAt the bottom of the canvas there’s a band where you let the paint drip down from the top. That sense of chance also reminds me of Cunningham and his collaborations with John Cage.

BMWhen I first started to show paintings, I did that a lot. I was making monochromatic paintings, and the drips at the bottom were an indication that they were handmade. It was at a time when a lot of painters were trying to make it look as though their work was mechanical, not made by hand. Later I stopped, though I’ve returned to it more recently with paintings like this one.

GLHow about the “East Coker” painting, Thira (1979–80)? It’s much more controlled.

BMIt’s all about opposites. Green and red are complements, and I tried to complicate the reading of it with the orange and blue. I’m always trying to mix colors in a certain way. I used to be, if not radical, then at least contemporary, and now I feel that I’m much more conservative. I’m still working with these ideas of color.

GL“Thira” means “door” in ancient Greek. You use the structures of post and lintel doorways in a lot of your work. The form looks like Stonehenge, which isn’t far from the village of East Coker. Eliot writes about old stones, old structures, in that poem, so it’s resonant.

BMI was thinking about the ancient dolmens and stone circles from the Burren in Ireland. Also classical buildings in Greece, with their solid and open spaces.

GLThe painting for “The Dry Salvages” is much more recent; I think you finished it this year. Can you tell me about it?

BMIt’s based on ideas of rocks from Japanese gardens, but it’s also about numbers. It’s all very unresolved. I’m drawn to the idea of the scholar’s rock, the artist keeping a rock in his studio as a microcosm or macrocosm. There are three clusters of rocks in the painting, and there are yellow horizontal lines, which mark off two-thirds of each of the rocks. That’s basically what the Japanese do—they bury two-thirds of the rock, so it’s coming out of the earth.

GLOr coming out of the ocean, in the case of this poem. The painting fits perfectly. It almost looks like a map of the Dry Salvages, the rocks that Eliot was writing about. For “Little Gidding” we’re using a much earlier image, which you made in 1980.

BMStructurally it’s related to Thira (1980). It contains some ideas from stained glass window studies I did for a Basel cathedral.

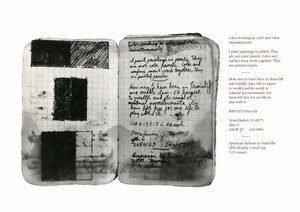

GLAgain the connections are uncanny; Little Gidding is a chapel, and the painting could almost be its windows. Poetry has been an important source for you in the past. In the 1980s you created a series of etchings to accompany a translation of thirty-six poems by the Chinese poet Tu Fu, and later a group of large canvases, the Cold Mountain series (1988–91), inspired by the Zen nature poet Hanshan.

BMYes, I discovered Tu Fu through the translations of Kenneth Rexroth, who himself was a great nature poet. I got very interested in Chinese poetry. I also love Yeats. I love poetry because it’s apparently so simple.

Special thanks to Noah Dillon, Tyler Drosdeck, and Caleb Hammons. Four Quartets premiered at the Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, on July 6–8, 2018, as part of the SummerScape Festival. It was co-commissioned by the Barbican Centre in London and the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA, and was performed at those venues in 2019 and 2020, respectively. For further information about Four Quartets, visit http://fishercenter.bard.edu/events/four-quartets/

Larry Gagosian celebrates the unmatched life and legacy of Brice Marden.

Eileen Costello explores the oft-overlooked importance of paper choice to the mediums of drawing and printmaking, from the Renaissance through the present day.

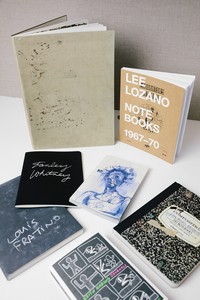

Megan N. Liberty explores artists’ engagement with notebooks and diaries, thinking through the various meanings that arise when these private ledgers become public.

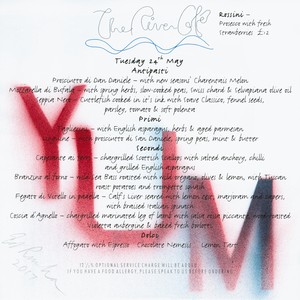

London’s River Café, a culinary mecca perched on a bend in the River Thames, celebrated its thirtieth anniversary in 2018. To celebrate this milestone and the publication of her cookbook River Café London, cofounder Ruth Rogers sat down with Derek Blasberg to discuss the famed restaurant’s allure.

Paul Goldberger tracks the evolution of Mitchell and Emily Rales’s Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Maryland. Set amid 230 acres of pristine landscape and housing a world-class collection of modern and contemporary art, this graceful complex of pavilions, designed by architects Thomas Phifer and Partners, opened to the public in the fall of 2018.

In honor of Robert Pincus-Witten, we share an essay he wrote in 1991 on Brice Marden’s Grove Group.

At the Royal Academy of Arts in London, Brice Marden sat down with fellow painter Gary Hume and the Royal Academy’s artistic director, Tim Marlow, to discuss his newest body of work.

With preparations underway for a London exhibition, we visit the artist’s studio.

Art for a Safe and Healthy California is a benefit exhibition and auction jointly presented by Jane Fonda, Gagosian, and Christie’s to support the Campaign for a Safe and Healthy California. Here, Fonda speaks with Gagosian Quarterly’s Gillian Jakab about bridging culture and activism, the stakes and goals of the campaign, and the artworks featured in the exhibition.

Sébastien Delot is director of conservation and collections at the Musée national Picasso–Paris and the organizer of the first retrospective to focus on Anselm Kiefer’s use of photography, which was held at Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain et d’art brut (Musée LaM) in Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France. He recently sat down with Gagosian director of photography Joshua Chuang to discuss the exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Punctum at Gagosian, New York. Their conversation touched on Kiefer’s exploration of photography’s materials, processes, and expressive potentials, and on the alchemy of his art.

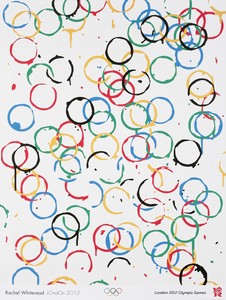

The Olympic and Paralympic Games arrive in Paris on July 26. Ahead of this momentous occasion, Yasmin Meichtry, associate director at the Olympic Foundation for Culture and Heritage, Lausanne, Switzerland, meets with Gagosian senior director Serena Cattaneo Adorno to discuss the Olympic Games’ long engagement with artists and culture, including the Olympic Museum, commissions, and the collaborative two-part exhibition, The Art of the Olympics, being staged this summer at Gagosian, Paris.

On the occasion of Art Basel 2024, creative agency Villa Nomad joins forces with Ghetto Gastro, the Bronx-born culinary collective by Jon Gray, Pierre Serrao, and Lester Walker, to stage the interdisciplinary pop-up BRONX BODEGA Basel. The initiative brings together food, art, design, and a series of live events at the Novartis Campus, Basel, during the course of the fair. Here, Jon Gray from Ghetto Gastro and Sarah Quan from Villa Nomad tell the Quarterly’s Wyatt Allgeier about the project.