Chiara Parisi is a curator and art historian. She was the Director of Cultural Programs at Monnaie de Paris, where she opened the new contemporary art spaces with exhibitions of Marcel Broodthaers, Maurizio Cattelan, Jannis Kounellis, and Paul McCarthy.

To juxtapose the work of Katharina Grosse and Tatiana Trouvé, artists whose directions are different but not altogether contrary in background, influences, and means, triggers new visual short circuits, frictions, and attractions at the Villa Medici, Rome. In their respective practices they share a fundamental interest in architecture. At the Villa Medici, this can create dialogue with unexpected and surprising outcomes, as well as generating tangible and psychological spaces that necessitate an active exchange, both physical and mental, with whoever investigates and traverses them.

The artists have been invited to participate in the fourth stage of an exhibition series entitled Une at the Villa Medici, the architecture of which is far from neutral, being stratified by centuries of history. The exhibition path that they construct, together and individually, twists and turns. For Trouvé, the space she investigates is made up of structures and symbolic objects, beginning with the Villa’s ancient Roman cistern. And through a reality reimagined, Grosse brings inside the exhibition a tree planted in the Villa’s grounds by Ingres.

For both artists, space is an extension of their studios, where their projects are conceived and formalized. For Trouvé, the Villa Medici, filled with symbols from other times, becomes a receptacle for her mental and sensual interventions that employ minimalistic structures and emotional distantiation. For Grosse, this same site represents a membrane shaped into a sensory path where painting becomes architecture and color is an anarchic element.

The immersive experience that the artists have created is guided, on the one hand, by the synchronicity of Grosse’s work, whereby the use of painting and the variable of unpredictability reign; and on the other by Trouvé’s obsessive study of the building of structures that are provisional, pliable, and adaptable, yet where the margin of improvisation is reduced as far as possible.

—Chiara Parisi

Chiara ParisiWhat was your point of departure for this project at the Villa Medici?

Tatiana TrouvéYou invited me to take part in an exhibition where two artists shared the rooms of the Villa: a double solo show. I reflected on this situation. Generally my projects begin with places, their architecture, their history, the physical and psychological scale of a space. This time it was the ways in which cohabitation redefines a space that guided my decisions.

On the one hand, I was very happy to share this invitation with Katharina Grosse, because for many years I have truly appreciated her installations; on the other, I have often thought that our works, although diametrically opposed, might be able to exist in dialogue. In this regard I thought of a novella by Italo Calvino, La giornata d’uno scrutatore [translated into English as The Watcher], whose story unfolds on election day. The protagonist, who is a Communist, is put in charge of overseeing a polling station at an institution for the mentally ill to ensure that the residents are not guided by the institution’s nuns and priests as they vote, favoring the Christian Democrats. He begins his day committed to his ideals but, in the end, realizes that those ideals rest on principles that have little to do with life, suffering, or poverty. He then asks himself if it is right for people to be able to vote or be assisted in voting, and he ends up admitting the following: Humanity reaches as far as love reaches; it has no frontiers except those we give it.

Beyond the political and democratic parable, what I take from this story, in relation to our exhibition, is how Calvino always affirms the power of doubt, which animates thought, and the contradiction that activates it. With doubt, or thanks to it, it becomes possible to perceive others, to understand their differences, the complexity of reality, and to no longer be content to play the game of questions and answers. For me, our exhibition and the cohabitation of our works is an opportunity to animate this doubt and to activate its contradictions.

CPSpace is an integral element for you. How have the history, architecture, and interiors of the Villa Medici influenced the genesis of the new works that you have made for the exhibition and your choice to include existing works?

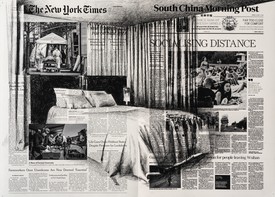

TTThe building was constructed in the Renaissance to replace the gardens of Lucullus, and even today, the superimposition of these two worlds still produces singular spaces. For me, the most interesting space is the ancient cistern, this sort of whale’s belly, a bit like in Moby-Dick. In my opinion it is a living organ that spreads out in the architecture and functions like a kidney. Here, the walls perspire, visitors’ feet are in the water, the air becomes thin, and light does not penetrate. All this would lead you to believe that some lumps of rock are pushing out very slowly; that the words uttered here are captured and will be heard in later years, or sometimes even be interrupted before they have been emitted. Inside the cistern, time produces incessant curves and loops: it is in a state of suspension. You enter the subconscious of the architecture. In this way you imagine that a visit to the show might last for days, even weeks.

CPDo you think that an unexpected short circuit will be created within the Villa, and also with the work of Katharina Grosse?

TTI would rather like it to entail an elaboration of space-time. My interest lies in combining many different concepts of space: a concrete but unusable space becoming abstract, and an abstract space that will prove to be more meaningful than how it immediately appears. As soon as you think you have stepped across it, you have in fact pushed it back behind you. Doubt settles in, and it is this disorientation in the space that allows a different experience of time to be asserted.

I believe that distortions are created between our works, places, and the visitors. An exhibition is always an unexpected event, even for the person who originates it. I discover my exhibitions just before viewers do, but always with surprise, and the duration or the precision with which I have conceived them is of little importance. They always demand adjustments on my part. I have never followed a preordained plan to the letter; on the contrary, I often put aside my initial plans once I am engaged in installing a work in the space. The exhibition is one of the most important moments in my work; the place of exhibition is a space of thought, within which I compose worlds, an extension of my studio.

CPHow do you think visitors will react to some of your existing sculptures in this new charged context of the Villa Medici?

TTI think about Sigmar Polke’s painting Can you always believe your eyes?, which I recently saw and which echoes precisely these concerns regarding the relationship of the viewer/visitor with works and exhibitions. And Muntadas’s statement: warning: perception requires involvement.

The visitor of an exhibition is caught between these two flows.

And then I need to have confidence in viewers, because the aesthetic experience is theirs. There are many ways to activate and animate the work’s potential, but the prerequisite is for viewers to pay attention. Paying attention is how the experience begins and it is what the experience leads to and prolongs. The attention one pays to a work multiplies questions about it: what meaning does one give to the presence of material objects in an uncertain symbolic sense (mattress, chairs, notebooks . . . )? What ritual or memorial purpose does one associate with them? In what physical or psychological reality does one situate them? How does this world work?

Each aesthetic experience belongs to us; it is unique and, in a certain way, unpredictable, both in the way it unfolds and in its outcome. It is impossible to foresee, to react a priori, to know if one still has to trust what one sees, if one should grasp things that surround us, this environment, calling upon personal cultural or social elements. To return to the words of Amerigo, the protagonist of Calvino’s novel, I would say that the only limits a work has are those one grants it. Its reading is always, also, the sum of what it puts together for us.

CPWhat would you take from this experience?

TTFor me, an exhibition is a ferryman crossing space and time; the works are transitional objects produced by these intermediary realities where dreams proliferate. They can pertain just as much to the past as to the future. Thus my hypotheses are open and are not assigned to a particular space or time.

Chiara ParisiWhat was the starting point of your new site-specific project for the Villa Medici?

Katharina GrosseFirst of all, I was looking for a spot in the Villa’s exhibition spaces where I could paint directly in situ. It had to be a surface that would allow my painting to connect with the Villa’s architecture and deal with its history in a paradoxical way.

When I found out that much of the Villa’s space is historically protected and therefore cannot be painted over, I realized that I would have to bring in cloth or other materials to create such a surface, a painting ground for a work that would be able to generate a sense of dislocation or independence. It was a lucky coincidence that we found the felled tree that is connected to the history of one of the villa’s most famous inhabitants, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

I decided to place a stack of tree-trunk sections on the horse ramp leading to the old stables. The ramp has gently inclining steps beneath a domed ceiling. Before the wood is piled on the steps, they will be partly covered in cloth, so that the tunnellike feel of this corridor will be accentuated. The wood sitting on the fabric will serve as my painting surface. Ultimately I think it will look like a cartoonish image of an oversized, disassembled canvas.

CPThe pine tree you are using was planted by Ingres when he was the director at the Villa Medici, from 1834 to 1841. Is your use of his tree in some way a nostalgic gesture?

KGI am not driven by a retrospective impulse but rather by the desire to project possibilities. There are many ways to look at the chopped-tree piece. Besides a disassembled canvas, it could be seen as a scaled-up fireplace; it might also refer to a wooden sculpture being painted as in medieval times, or it could feel like brutally disrupted growth.

History as the construction of linear development does not make sense to me. This is why painting is so fascinating to me. Everything in a painting is present at the same time. The “before” and “after” completely depend on one’s choice of perspective.

There is no one right way to look at the work; it provokes one to move around, in, and through it in the attempt to put it together in one’s inner vision.

CPCould we say that you are taking the very charged object of the tree (connected to the architecture, the gardens, the city) and are reusing it as a sort of totem/agent? You seem to be reversing Ingres’s gesture by displacing the tree from the outside to the inside. By incorporating this dead matter into your work, you are opening a new chapter for it.

KGThe pine tree was planted in Ingres’s time and grew into our present. It’s extraordinary to think that the lifespan of a tree so far surpasses that of a human being. Ingres’s own work does not matter here specifically, but he is the magic ingredient. Ingres, who planted the tree to create a framework for the ancient Dea Roma (Rome as goddess) statue in the garden, infiltrates the crude tree-trunk sections with a story that the wood itself fails to represent. In that sense the tree is the abstraction of Ingres’s very existence. This tree also allows me to create a sense of displacement or “misbehaving” indoors.

I transform the space, the material, and its history. The felled tree is the very metaphor for that. That is what all artists do: they paint over other artists’ work, and yet at the same time that work stays present. But again, I want to stress that the tree was a lucky find; my paintings can land anywhere anytime. In this sense they are exactly like thought. I believe that paintings can transform our understanding of everything—from the most intimate to the broadly political. Looking at paintings makes us realize that things look different every time we look at them, even if we console ourselves with the familiarity of a revisited situation. It is a simple but powerful move to really feel that everything is different every time, that we do not need the big solution once and for all, but that constant change is natural. Embracing uncertainty in such a way could influence how we look at gender, race, society, or politics.

CPIn that aspect, to what degree are you actually working on the concept of “Überformung” (reshaping the surface of reality) by applying paint to the previously chopped-down tree?

KGThe relationship of my painting to the sculptural surface is a paradoxical one. Built space and painted space stand for qualities that normally exclude one another but that here occur at the same time. Color is atopic; therefore it allows me to paint a large watercolor in difficult circumstances—in this case on tree-trunk sections placed on fabric. The painting gains an illogical tactility and resists arriving at a homogeneous image. Because of this it forces us to experience the world as discontinuous and fragmented. I think that the exaggerated fragmentation questions our need for harmony and shows us the impossibility of experiencing the world seamlessly.

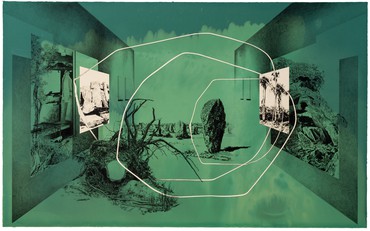

CPIn the exhibition, you also present a copy of your very first spray painting, printed on silk to actual scale. Can you discuss the original work, its reenactment, and the particular choice of display in Rome?

KGThe green corner was my very first in situ painting, at the Kunsthalle Bern fifteen years ago, and remains an important referent in my work. Working directly in the exhibition venue is more exposed than working in the studio, bound to the visual conditions of the setting with regard to time and subject. The manifestation of a work is tied to the site but its level of impact is not.

For the viewer of the original work, the photographic documentation of that work does not do it justice and, conversely, the missing original exercises great fascination over the viewer of the photograph: to see the thing that she never experienced firsthand. Thus the 1:1 reproduction of the work is a deception in itself, revealing—at actual scale—that the work itself is absent.

Tatiana felt strongly this “apparition” of the green corner would resonate with a set of sculptures she had. We started to realize that our works could interlock and stimulate loops of exchange.

CPThe nonhierarchical understanding that a painting can appear everywhere is also strikingly expressed in your outdoor works, where your paintings stretch over vast landscapes.

KGThe strategy of my outdoor works is to implement a seemingly natural scribble into “nature,” which lets us reassess how we think about “nature” when we give it form. My painting intends to stage our imagination of the natural; one could even spin this further and say that my imagining of the natural in the form of a painting leads us to rethink our imagining of the garden as idealized nature. I want to touch upon questions such as, How do we create a form of nature? And how do we deal with the consequences of this process?

CPWould you say that you have something in common with Ingres?

KGWe clearly share a love of gardening!

Katharina Grosse and Tatiana Trouvé: Le numerose irregolarità, French Academy in Rome, Villa Medici, February 2–April 29, 2018