Jean-Michel Geneste is archaeology field director and research coordinator at PACEA, CNRS Laboratory, Université de Bordeaux. He managed France’s primary national rock art research institution, the Centre National de Préhistoire, directed the Chauvet Cave International Research Program, and was curator of Lascaux. He has contributed to many scientific films and publications on subjects related to the origins of human art and behavior. Photo: Pascal Hanrion

Tatiana Trouvé’s work blurs the boundaries between “interior” and “exterior” both materially and mentally. Mental images are materialized in space and become concrete, while domestic spaces merge with natural spaces. Her situations combine drawings and sculptures both linear and three-dimensional, and spaces that hint at invisible dimensions. Photo: J.C. Mazur

Jean-Michel GenesteYour work stirs up all kinds of reactions and interactions with my own archaeology practice, and with my relation to the world in general.

Tatiana TrouvéI’m fascinated by the links you make across time.

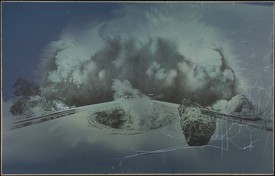

JMGI would first like to talk about your installations, in particular their use of natural environments or elements. For your recent installation at Orford Ness, on England’s southern coast, you used both existing aspects of the site, such as the landscape and buildings, and your own interventions. The materials you incorporate often have anachronistic connotations, by which I mean there is a very unexpected and striking way of combining different materials.

I see this dissonance throughout your work. In your Guardian series, for example, you have taken chairs with presences that signify absence—personal objects that appear to have belonged to somebody and suggest a status or an action, or the imprint of a body on a cushion, implying movement. What’s more, you set those ephemeral elements in solid materials: bronze, copper, marble, or semiprecious sculpted materials. It reminds me, in a way, of classical sculpture. The last time I was in Rome, I saw Bernini’s Blessed Ludovica Albertoni, whose mattress and cushions evoke those of Sleeping Hermaphrodite, in the Louvre. The softness of the cushions and the mattress on which she is lying is the same softness you attain with materials such as multicolored quartz. Those contrasts create a tension, stimulating our imaginations in an unexpected way.

TTI can understand why you’re interested in that series. As it happens, the other day I was looking at Si loin, si près [So far, so close], a book you wrote three years ago. There is a beautiful illustration featuring needles, and you explain your practice very well with the expression “looking for a needle in a haystack.” When you find a needle, you can deduce that prehistoric humans knew how to sew, but there are no signs of clothing. These are the voids you seek, voids that have, so to speak, their own traces. You spend your time restitching elements together, unearthing presences.

JMGYou’re absolutely right. But with me, it’s on an intellectual level, whereas your work deals with matter.

TTI think they are always related. To me, form is sedimented content. When I put a bag and a book together with a jacket, and all three are transformed into ancient materials, they tell a story that is at once very close and far removed from humankind.

JMGYou reuse solid materials, which last much longer than ideas—

TTI think the objects are actually inseparable from ideas; they carry ideas because each material contains a world of its own. When I see a rock, I see how the world was sedimented; the way we see bronze is related to our culture. So, all the materials I use are also laden with ideas and their history.

JMGYou don’t represent the human figure but instead depict ideas, thoughts, and intellectual, artistic, and human situations. How did this decision to avoid human representation come to you?

TTThat’s a great question, and it’s one I ask myself often. I think I don’t actually avoid representing human figures; rather, maybe they’re at the heart of my work precisely because I don’t represent them. To understand someone means understanding how he or she interacts with other people, with the rest of the universe, with other species . . . But to make a portrait of somebody means doing something else; you’re no longer actually representing a person. What I do is to provide clues for us to imagine a person’s life, their relation to the world they inhabit, the range of possibilities available to them. Human figures are present in my work in that way, whether I’m creating huts or guardians or even installations.

JMGWhat you’re saying is tangible in your work, and it also applies to prehistoric art: in cave art, there are no humans, but in the situations depicted there is a human presence; the paintings have clearly been designed by humans, who by selecting rhythms, positions, and shapes have established a context we can see and feel 30,000 years later.

What immediately appealed to me in works like the Guardians is the essential role of the materials. I feel a certain tension between your highly technical use of material on the one hand, and on the other, the way you use these techniques in psychological, social, artistic, and imaginary realms, which often even affects the unconscious.

When I put a bag and a book together with a jacket, and all three are transformed into ancient materials, they tell a story that is at once very close and far removed from humankind.

Tatiana Trouvé

TTYes, that’s true, I had never thought of the fact that I use elements that are extremely archaic and that I employ very ancient skills, like stone sculpting and bronze smelting. There is a paradox: I use these very ancient materials and techniques to talk about very contemporary subjects, sometimes related to biology, anthropology, world history, and so on—subjects that, when placed on such an ancient scale, can seem merely factual. But I like using these ancient skills to understand the world around us. Often, the books accompanying the Guardians concern biology, anthropology, history, feminism, politics; they are some of the tools that enable us to understand a very open-ended world.

JMGHow did this language of transformed archaic materials and skills come to you? Was it an intentional invention or something that you gradually developed?

TTIt’s hard to say, but I think that from the very beginning, at art school, I began to have a relationship with form and this quickly led to materials. It happened in a very spontaneous and intuitive way; I was compelled more than anything else. I haven’t made a single painting in my whole life, I’ve always made drawings and sculptures.

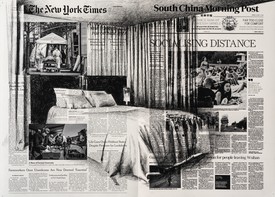

JMGI think of one of your most recent exhibitions with Gagosian, which featured graphite-heavy drawings, where you used a special technique to draw on newspapers and dailies. The materials were ephemeral, but you used a technique particularly adapted to them. And I got the impression that there was something intuitive at heart.

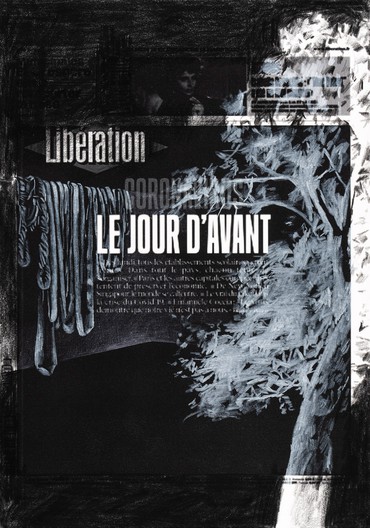

TTI think my first gesture was intuitive, because it all started with the 2020 lockdown, the first global lockdown in history, and more specifically with the front page of the French newspaper Libération, which said “The Day Before” in reference to the disaster movie The Day After Tomorrow. We didn’t know what was happening, we only knew that we were going to be confined to our homes, and the first thing I thought was: “If that was the day before, what is going to be the day after?” So, like everyone else, I started following all that was going on using newspapers and dailies. The series quickly grew day after day, becoming a sort of pattern: I would read about how the pandemic was developing and would then draw on newspapers’ front pages, like a private journal. It was an interesting situation, because while newspapers were facing a steep decline in their physical sales, they were receiving widespread attention on social networks. It precipitated the end of print media in favor of digital media. So, I was drawing on something both obsolete and absolutely contemporary. I think it was a testimony to that strange period brought about by covid.

JMGYes, the way you expressed an urgent situation in a world undergoing a great convulsion that brings forth new perspectives was extremely powerful. And at the same time, the way you worked with an ephemeral material with a daily alacrity was in tune both with the era and with something deeply human within us. Even with the gray color palette of the materials you chose—graphite and newsprint—there was a vibrancy in those daily pages. Like the way paper is blown by the wind, we wonder whether those traces will last.

On the subject of traces, I saw that you read books by people who have written about anthropological traces, on biology and the behavior of primates, and you chose a number of books that deal with anthropological and ultimately human questions. Your choice of subjects strikes me because you cannot be an archaeologist without working on clues and traces. One author you cited, Giorgio Agamben, has written wonderful texts about the role of clues in the emergence and construction of human knowledge and even, in a certain way, of humankind. You confer a deep significance to traces by giving them a form, sculpting them using durable materials. It makes me want to ask you: although traces are short-lived, you make works destined to have a great longevity. How do you imagine your works’ future? What will become of the Guardians in forty years?

TTI think of time on such a small scale compared to the scale of prehistory. You mentioned Agamben and the importance of traces and clues in his thinking—I would add that he is among those rare philosophers whose understanding of the contemporary world is also constructed from forms of art. But there is also Carlo Ginzburg, the Italian historian who wrote about micro-clues—about how we can reconstruct history using clues, despite missing elements. What’s missing becomes fiction because certain rules stipulate that there are things we can only imagine. I believe that my Guardians will always be imagined. They will be looked at differently, to be sure, and they will be looked at like people who have aged, living in worlds that have aged. I like to think that everything ages when you look closely at it—even bronze gets sick, develops cancer, little by little, and stone never stops oxidizing and altering.

Similarly, we won’t see all those books, stories, and worlds that the Guardians are trying to defend, preserve, or display in the same way—they’ll be seen according to other discoveries, to things that will have disappeared and others that will have appeared. I like to imagine that although the objects are factual and are the traces of humble lives, the material quality of stone and bronze will elevate them. The materials I use are materials we always want to touch because by touching them, we burnish them and alter them. They will always be strongly bound to us. I also believe that our fascination with materials and stones, whether we believe it or not, is linked to the beneficial or maleficent effect that they can have on human beings. We will always be incredibly fascinated by materials with which we have interacted since the dawn of time.

JMGYou mentioned Carlo Ginzburg, an anthropologist and historian who has guided me in my work and who has influenced our whole discipline. I’m especially interested in the list of books you’ve chosen to be included in the Guardians, sculpted in marble. It is such a magnificent idea: that words and speech, ephemeral as they are, be set in multicolored marble. This symbolism alone is incredibly poetic, but you also channel their specific content. They all touch upon advances in knowledge, in the understanding of animals and the world as a whole. How did you make the selection?

TTI choose from personal interest. They’re all subjects I’m profoundly interested in. If I had not been an artist, maybe I would have been a biologist or an anthropologist. I love learning about other systems, nonhuman life, about their world, how they see ours and how we see theirs, the ways we can live together. Here’s a very simple example: as a human, when I see a tree, I see the fruit, or the wood that can bring me heat, but if a bird sees a tree it sees a place where it can build a nest, or the branch it can land on. Even though we see the same things, we see them very differently, they send us radically different messages. I’m interested in all the people who try to understand these worlds. The universe we live in is so fascinating, it defines us as much as we define things around us. That forms part of my interests, but I love stories and fiction as well. And some of the books in the Guardians are not actually books, such as [Fernand] Deligny’s Grande Cordée. There are all these wonderful worlds I’m trying to save before everything disappears—or rather, these are the people who study these worlds and try to understand them before everything falls into oblivion. Maybe that’s also what my Guardians are trying to protect.

JMGYour work is part of a series of movements and discussions spanning disciplines and arts, from literature to philosophy, that question humankind’s relationship with other beings. Very early on, humans understood that their existence depended on their ability to coexist. Today, we have completely forgotten that. You can picture a kind a pyramid where we might be the last to appear in the series of complex beings, but the rest of the pyramid has kept us alive—and now we are undermining it. It’s an idea that many philosophers have studied, such as Baptiste Morizot, who writes particularly well about the subject, and is also an activist. Coexistence is jeopardized by a great paradox: humans’ major issue is that they have to coexist with one another. Day after day, we see that this is the most difficult thing, more difficult than coexisting with other living beings.

TTI think that if we do not sort out our way of coexisting with nonhumans, we will never be able to coexist with each other. We carry on harming each other because we allow people to do terrible things to other forms of life. If this is acceptable, then it makes it easier to think another human is worth less than we are. Substantial work needs to be done.

JMGYes, and there is a great movement taking place at the moment that is rallying all forms of thought and intellectual and spiritual activity. We can see how it brings people together, but we also see how results are interpreted in a political way, how politics appropriates ecology, and for what?

I see that you chose fundamental works about our relationship to the environment and to ecology. It’s very important to quote source texts and not political attitudes or decisions, which are often completely inadequate. That’s why I highly appreciate your having quoted Bookchin and Thoreau, for instance. It is important to return to the roots of those ideas. We might ask ourselves, what do those authors have to do with our own times?

TTThey’re foundational. They were not caught in political speculation. Thoreau did fundamental work.

JMGYes, they are original, in the sense that they were the first; they were handling pure, untouched ideas.

TTIt wasn’t greenwashing, that’s for sure!

JMGWe have talked about a great many things. In relation to my concerns about the origins of representation, your work maintains a balance between its material aspect and the implicit spiritual significance. And it accomplishes this with such rigor that I find it vital and exemplary, especially when considering your choice of contemporary methods. What appeals to me in a contemporary artist is how he or she renews methods, not necessarily forms. But you renew everything, with a profoundly moving open-mindedness and generosity. Each time I speak with you, I learn things about method. I find methods more convincing than speeches.

All artwork by Tatiana Trouvé © Tatiana Trouvé