Wyatt Allgeier is a writer and an editor for Gagosian Quarterly. He lives and works in New York City.

“Poets when they write about other artists always tend to write about themselves.”1 So wrote the poet John Ashbery about Gertrude Stein, and as true as it is of her, it is just as true of Ashbery himself. Indeed the statement presages the poem that would cement his poetic legacy some three years later, “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” of 1974. The poem, which takes the sixteenth-century Parmigianino painting of the same title as both subject and vehicle for introspection, pushes Ashbery’s thoughts on Stein to their full-bodied conclusion, engaging in a play of selves and surfaces that reflect back images of both the painter and himself, the poet, in equal measure.

“Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” was published in 1975, the centerpiece of a collection of the same name that would become Ashbery’s most dazzling success, winning a trifecta of prizes—the National Book Critics Circle Award for that year and both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for 1976. The multilayered title poem remains Ashbery’s most famous work to engage so directly with the visual arts, but he was in some manner always writing with and through the aesthetic realm. As early as his childhood in Rochester, where he took painting classes at the city’s Memorial Art Gallery, Ashbery was dazzled by the magic of the visual. By the 1950s, his was a full-fledged curious eye discovering the works of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko in New York City.2 Of those years he would later remark, “American painting seemed the most exciting art around. American poetry was very traditional at that time, and there was no modern poetry in the sense that there was modern painting. So one got one’s inspiration and ideas from watching the experiments of others.”3 In the next decade, first as a Paris correspondent for Artnews (1963–66), then as the magazine’s executive editor (1966–72), Ashbery would continue to watch these visual experiments, which provided a cache of conceptual and visual material available for integration into his poetry.

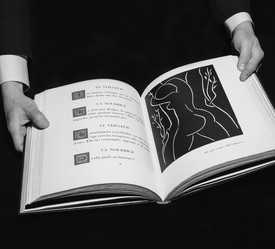

Grasping this symbiotic relationship between the poet and the world of visual art, the Arion Press published the most apposite version of “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” in 1984, on the poem’s ten-year anniversary. Made in an edition of 150, this striking livre d’artiste, in a clever marriage of form and content, deftly reifies the philosophies and observations at the heart of Ashbery’s poem. From the start, the stainless steel case, which mimics the design of film canisters, aims to echo the concerns reared by Ashbery’s lines. Housing forty unbound sheets, the case has as its center a convex mirror. Here, the reader, too, gets to partake in a “life englobed.”

. . . This otherness, this

“Not-being-us” is all there is to look at

In the mirror, though no one can say

How it came to be this way. A ship

Flying unknown colors has entered the harbor.

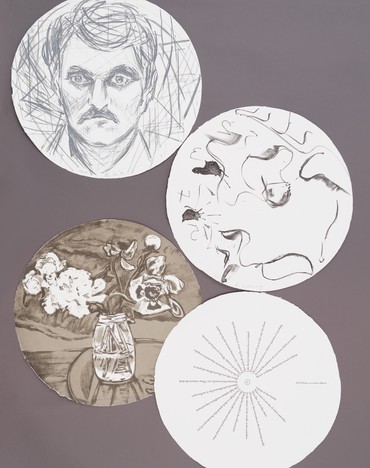

Inside the canister, on handmade circular pages, each eighteen inches in diameter, the publication continues its loyal interpretation of the poem. Eight artists were enlisted to contribute original works. Most of them, such as Jane Freilicher and Larry Rivers, were longtime close friends of Ashbery.4 Logically, the eight prints, also on circular sheets, partake in the same thought-work as the poem, using lithography, woodcut, etching, and other methods to consider the relationship between the creative act and the slipperiness of the self. In addition to Rivers and Freilicher, Richard Avedon, Jim Dine, Alex Katz, R. B. Kitaj, and Elaine and Willem de Kooning contributed work.

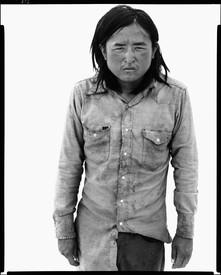

Avedon photographed Ashbery reaching into his blazer. (For a pen? A mirror?) Rivers overlaid a typescript of Ashbery’s poem “Pyrography” (1977) on a drawing of the poet in profile, dutifully typing away. Katz’s female subject mirrors Parmigianino’s pose in the original self-portrait, particularly the artist’s intensely present hand. Willem de Kooning responded abstractly with wisps of lines undulating on the circular page, a hint of numbers around the edges like a clock evoking the temporal unease of the opening lines from Ashbery’s third strophe:

The balloon pops, the attention

Turns dully away. Clouds

in the puddle stir up into sawtoothed fragments.

I think of the friends

Who came to see me, of what yesterday

Was like. A peculiar slant

Of memory that intrudes on the dreaming model

In the silence of the studio as he considers

Lifting the pencil to the self-portrait.

How many people came and stayed a certain time,

Uttered light or dark speech that became part of you

Like light behind windblown fog and sand,

Filtered and influenced by it, until no part

Remains that is surely you.

For the poem itself, Arion Press set the lines of Ashbery’s text radiating out from a central circle containing the page number, like spokes from a wheel or rays of light from an iconographic sun. If not exactly user friendly, the effect is nonetheless thematically precise and visually stunning. And since, below the leaves of art and text, the publication includes a vinyl record of Ashbery reading his poem, one might reasonably forgo the spinning motion required for reading, choosing instead to sit back and listen as Ashbery’s singular vocalization transports them like a “carousel starting slowly / And going faster and faster.”

By including this vinyl recording, the publication continues its faithful, formal understanding of the influences girding Ashbery’s works, for the album, through association, ties in the crucial dimension of music. As Ashbery said, “Communication is what interests me in poetry. . . . What I like about music is the persuasion that takes place, though one is not aware of it. At the end of a Bruckner symphony one may rise to one’s feet to applaud. One receives a message without knowing one has been told.”5 Or as he writes in “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror”:

That is the tune but there are no words.

The words are only speculation

(From the Latin speculum, mirror):

They seek and cannot find the meaning of the music.We see only postures of the dream,

Riders of the motion that swings the face

Into view under evening skies, with no

False disarray as proof of authenticity.

But it is life englobed.

1John Ashbery, quoted in David Herd, John Ashbery and American Poetry (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), p. 70. The original source is the February 1971 edition of Artnews, where Ashbery was writing on an exhibition of Gertrude Stein’s collection at the Museum of Modern Art.

2See Richard Kostelanetz, “How to be a difficult poet,” New York Times, May 23, 1976. Available online at www.nytimes.com/1976/05/23/archives/how-to-be-a-difficult-poet-john-ashbery-has-won-major-prizes-and.html (accessed March 20, 2018).

3Ashbery, quoted in ibid.

4See ibid.

5Ashbery, quoted in ibid.

Artwork © 2018 The Richard Avedon Foundation, © 2018 Alex Katz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, © Elaine de Kooning Trust, © 2018 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, © Estate of Jane Freilicher, © 2018 R. B. Kitaj, © 2018 Estate of Larry Rivers/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY, © 2018 Jim Dine/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York