Norman Diekman studied at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, and worked in architecture with Philip Johnson, Lee Pomeroy, and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. He also worked with Ward Bennett in furniture and product design.

Douglas Flamm has over twenty years of experience in the field of rare books and began working as Gagosian’s rare-book specialist in 2016. He works closely with collectors, helping them to enhance their book collections by sourcing scarce and important material.

Douglas FlammCould you tell me when your love affair with art and architecture books began?

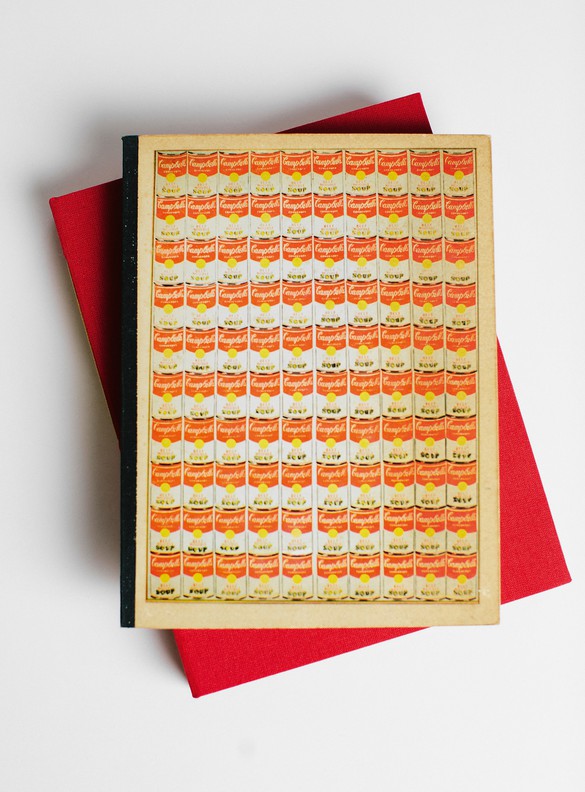

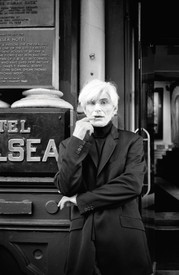

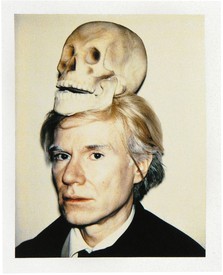

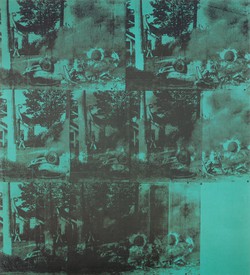

Norman DiekmanI finished high school in 1958 and went on to study architecture at Pratt. I had a fabulous teacher there; he would instruct us to go to the Museum of Modern Art bookstore, as well as several others. I learned a great deal from these trips, but the real beginnings commenced when I landed a job at the architect Philip Johnson’s office a few years later. Books arrived frequently in Johnson’s office, mainly from Germany and Italy. They were beautiful publications of all different sizes and kinds. He was so generous, a real gentleman, and I think he could tell how excited I’d get when they arrived; he would tell me, “Norman, I’ve got this book, take a look at it.” Eventually he would even let me take a book away on the weekends. So then I’d ask him, “Where did you get this or that?” He introduced me to Wittenborn & Co., at 1018 Madison. From that day forward it was a Saturday visit to Wittenborn’s every week. They had wonderful things. One of the first books I bought there was an Andy Warhol catalogue from Philadelphia for $3; I still have the receipt.

DFIs that the 1965 Samuel Green catalogue from the ICA?

NDYes, exactly. At Wittenborn & Co. I had my first look at Drawings for a Living Architecture [1959], the Frank Lloyd Wright book; that book blew my mind. It was as if you’d opened the filing cabinets at his studio, Taliesin, and you had a free look at all the drawings you wanted to. Absolutely beautiful. At the time, I didn’t have the money—$35 and money was tight! Next time around, $60, same thing. Finally I had money when it was about $600, and that’s when I bought it.

DFJohnson was really a pivotal figure in igniting this passion, it would seem.

NDYes, I would say he was pivotal. You know, I came from a poor family and things were difficult. I had financial trouble getting through college at Pratt, and Johnson helped with that.

I’ll tell you one story: one day Mr. Wittenborn was telling me about a time Johnson came by his store in Berlin, which he had owned before coming to New York—he had heard I worked for him, and if people like Wittenborn and others heard you worked for Johnson, they treated you very nicely because you were connected to a man whom they adored. It’s like if you worked for Leo Castelli. He told me about a time when Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock were researching for their co-curated exhibition Modern Architecture: International Exhibition [1932], at the Museum of Modern Art, and they stopped by the Berlin store. He said they arrived in a silver Rolls-Royce [laughter], and they filled the Rolls-Royce with books! Wittenborn had suffered through the awful economy in Germany before Hitler, and he and everybody else in the store found the whole thing so amazing. He always remembered that. I guess that may have played some role in his coming to America, which is nice.

DFEven from early on, the books you were buying seem to have informed your practice as a designer?

NDYes, they were a source of inspiration. The number one, and number two, of my passion was the excitement of seeing something I hadn’t seen before and never even thought possible to do. When people asked me about the furniture I designed, I would tell them my influences were artists and architects. Architecture books from Germany, Italy, and burgeoning presses in New York were suddenly available in Wittenborn’s shop and, later, Ursus.

DF Were there books that you’d seen before, at work or on some other occasion, that you actively began searching for when you were able?

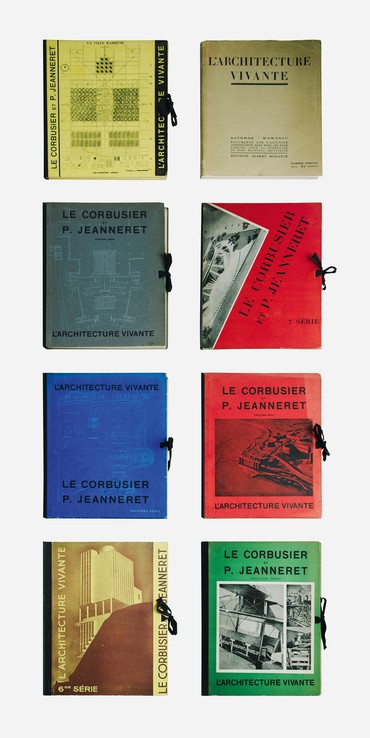

NDYes, I remember being keen to acquire books on Mies, anything on Le Corbusier, and Charles and Ray Eames to a degree. One time I was in New Haven and I went to visit Josef Albers to try to have a chat, but unfortunately he was out. His daughter was at home and she was very gracious, she told me, “You can wait, they might be coming back.” So I sat in the living room and I perused their bookcase, jotting down book titles at Albers’s house, and afterward I pursued them. It was a full-formed passion by that time.

DFDid Johnson tell you about any books that remained elusive for a certain time, but that you—

NDI remember falling in love with the Maison de Verre while working with him, but being unable to find a proper publication on it.

DFYes, the Maison de Verre is interesting in that reproductions of it took so long to be published; it really wasn’t until that GA book came out, in its expanded version in 1988, that we had decent illustrations.

NDYes, when that special issue of the GA came out, I was in the Prairie Avenue Bookshop in Chicago. I was chatting with one of the proprietors and we went into the back to look at the new arrivals. I was so, how do you say, “good” in the bookshops that they let me into the back room. The secret was the back room. It was the same in the back room of Castelli’s—they’d let me look around, I’d see something in the back, not on display outside. I purchased a John Chamberlain sculpture that way! Anyway, she opened the box and there on the top is the Maison de Verre book with the blue cover. I flipped out! I looked through the pages and I said, “Oh, you’ve got to sell me this!” I walked out with that book and I was so happy. You could build a Maison de Verre from that book if you put your head together; it was so exciting to get all of those details.

DFWhat have been some other exciting finds?

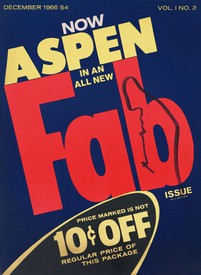

NDAt one point I was buying a lot of books by or on early Le Corbusier. I went and bought Quand les cathédrales étaient blanches [When the Cathedrals Were White], published by Librairie Plon, Paris, in 1937, for $3. I was also excited when I found a first edition of Learning from Las Vegas [1972] by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour. I got Robert and Denise to sign it later on. The graphics were interesting because they were a touch on the Pop art side, with real contemporary graphics from billboards, TV, and so on.

DFYes, it’s a larger format.

NDI had it for a long time and then, when I went to sell it, I got $3,000 or something like that, which I thought was terrific. I came home after selling it and I found the receipt, and I’d thought I’d paid about $350 or something, so I thought I’d made good money. I look at the receipt and I see I paid $175!

DFIt’s clear that a book’s content was a chief concern in your collecting—you mention Frank Lloyd Wright, Venturi. But does the book as a design object itself hold interest for you, as well?

NDOh yes, of course. One of the best is Des canons, des munitions, the Le Corbusier book from 1938. Des canons, des munitions is the power book, and frankly, you buy it for the cover and that inside color page.

DFI’m sure you came across copies in poor condition. Was the condition of the publication an important piece of the puzzle for you?

NDAbsolutely. I was finicky in a way. That’s why I didn’t buy very much from the Strand; Strand books look like they came out of an artist’s studio that was a barn somewhere. There were drips and humidity. I also found out to be careful about buying books in East Hampton because the salt air would get in them and then you’d find out later. Although I did buy a signed Roy Lichtenstein at the Guild Hall museum for $35, which I thought was great. I wish I could have bought five!

DFDid you like collecting signed books?

NDWell, I liked meeting the artists and asking them to sign. Most of them were very cordial. I went to a lecture at the Guggenheim on the Peter Lewis House that Frank Gehry was designing. I went up afterward and asked Mr. Gehry to sign the book. He said, “Okay,” and then he turns around and says, “Peter, Peter, come over here, sign this book for this chap.” It was like a shared experience, he didn’t just walk away, which was so nice. Ed Kienholz did the same thing—he wrote a nice inscription in his book and then he said to his wife and collaborator, Nancy Reddin Kienholz, “Nancy, this young man enjoys our work, sign the book.” He was jolly about it.

DFAre there other people besides Johnson who helped inform your collecting of books? You mentioned you would go to Wittenborn on a weekly basis, and to other bookshops—is a relationship with the bookseller an important part for you?

NDYes, I have to have a rapport with the dealer. The civility of the experience counts for a great deal. Seymour Hacker of Hacker Art Books was always an interesting experience. I thought he was sour for the longest time, but we developed a mutual respect and rapport. He was from the Abstract Expressionist generation and he enjoyed discussing art, knowing what the new generation of artists was doing.

DFIt sounds as though, in the beginning, you bought what you stumbled upon and what caught your interest. At what point did your collecting become more systematic and methodical? Looking at your collection, you clearly developed an interest in certain series or publishers.

NDI can’t remember when I first discovered Ettore Sottsass, but I recall thinking that he was incredible; his whole attitude to interiors, furniture, and architecture was astonishing. I quickly began to search methodically for anything published by Sottsass. For a while, anytime I went to a bookshop, I’d ask that they let me know if anything came out by Ettore.

DFIn addition to collecting architecture and design books, you also put together a significant art library. Was there, in your mind, a dialogue between the two?

NDDefinitely a private dialogue between the two libraries and in regards to my own work.

DFYes, you mentioned that your work was inspired more by fine artists than by other designers and architects.

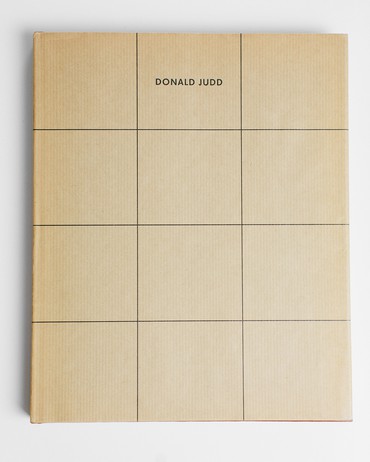

NDAbsolutely. Once I got completely hooked on book collecting, I was living in a time, and I and my books were defined by that time. Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol: I was living in their world. If a new book came out on Warhol, I was interested in having it, even though the same pictures were in it, but they were in it in a different way and the text was different, the stories were different maybe. It was the same with Anselm Kiefer: I had almost twenty Kiefer books at one time. I got to a point where, honestly, and it may be silly, but I got to a point where I was buying a book for one photograph! This happened mainly with Cy Twombly. There’d be a Twombly sculpture that I hadn’t seen in any other book or any other place and I just wanted to keep looking at that sculpture, so I’d buy the book.

Photos: Carey MacArthur