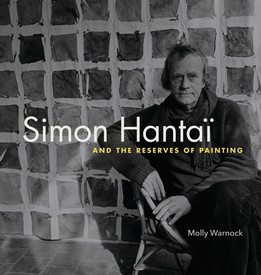

Staffan Ahrenberg is a Swedish art collector, entrepreneur, film producer, and the owner and publisher of Cahiers d’art, the legendary journal that he relaunched in 2012. In 2018, Ahrenberg was honored as a Chevalier de l’ordre des arts et des lettres in France. Photo: Staffan Ahrenberg Archive

Douglas Flamm has over twenty years of experience in the field of rare books and began working as Gagosian’s rare-book specialist in 2016. He works closely with collectors, helping them to enhance their book collections by sourcing scarce and important material.

DOUGLAS FLAMMFor those unfamiliar with the history of Cahiers d’Art as a press, could you give a quick synopsis of its founding?

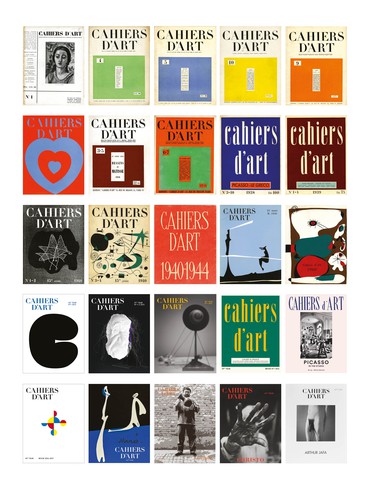

STAFFAN AHRENBERGThe founder of Cahiers d’Art, Christian Zervos, was from Greece—born in Cephalonia and educated mainly in Alexandria, which was really the place for the intellectuals at that time. He was born shortly after [Pablo] Picasso. He came to Paris in the 1910s and continued his studies, and in 1926 started the review Cahiers d’art [also known as La Revue]. Cahiers d’art translates simply to “art notebooks,” but cahiers in French also has the connotation of a literary or artistic review.

DFHe started it on his own?

SAYes, there’s a great book on this history published in 2019 for an exhibition at the Benaki Museum in Athens. Written in both Greek and English, it chronicles the whole history, year by year, and includes documentary material. Looking at the history, you could see he always had a passion for publishing. After creating the review Cahiers d’art, Zervos launched an eponymous publishing house and gallery. Very quickly, one could see what Zervos did differently from the few peers he had. First of all, he had a very good sense of typography and design, and he really wanted to illustrate the images in a strong way. He himself wrote a lot for the review and he had many great poets and writers contributing. And he mixed the European contemporary art of his time with African art, Chinese art, lots of Greek, Hellenic, and Cycladic art. He published and wrote incredible books about a wide array of art.

If you think of his peers, one was Tériade, who worked with him and later went on to start Verve. Verve is a wonderful publication but it is very different from Cahiers d’art. Issues of Verve are more like picture books.

DFDerrière le miroir is another good comparison; it was a combination of an exhibition catalogue and a stand-alone monograph. But Derrière le miroir didn’t have the sort of serial aspect that Cahiers d’art did.

SAYes, it was singular.

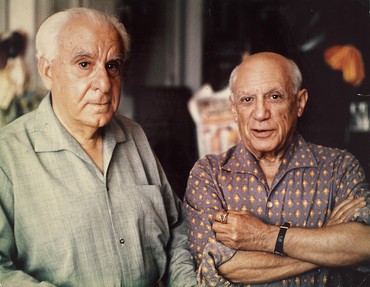

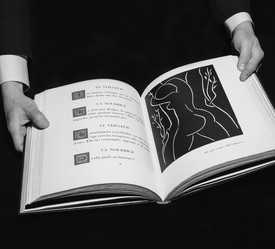

Zervos launched the first issue of Cahiers d’art with [Henri] Matisse in January 1926. Gradually the review grew to become thicker and gained renown. In 1928/1929, he met Picasso, and I think it was in 1929 or 1930 that they first spoke about publishing his catalogue raisonné, something Picasso wanted to do. The two of them got along very well and the catalogue raisonné became a sort of life’s work—I would say he had two life’s works, for his other life’s work was the publishing house itself with the review and the books. The gallery was another story and was run by his wife, Yvonne; he really didn’t work from the premises. He created the books and reviews directly with the authors and artists.

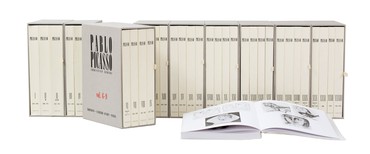

He published the first volume of the Picasso catalogue raisonné in 1932. In reality, he had no idea it would be so many volumes.

DF[Laughs] I mean, that’s why I think it became a life’s work.

SABoth men died while working on it. It took forty-six years to make the raisonné, or the Zervos, as it’s known today. It is really the bible of Picasso, and it’s still unfinished, but we do have plans to complete it at some point. Irrespective of that, it stops in 1978. What’s interesting is that Zervos died in 1970 and Picasso in 1973, and when Zervos died, Picasso wrote a letter to Cahiers d’Art saying, You must continue my catalogue in the same style and manner as before, et cetera, dated 1970, signed by Picasso. And so when Picasso died it continued. I would say that by the time Zervos passed away, maybe eighteen volumes or so had come out, with the remaining volumes published between then and 1978.

Each volume of Cahiers d’Art was groundbreaking; [Zervos] was presenting things that hadn’t been published before. He wasn’t just recycling other ideas.

Douglas Flamm

DFIt’s remarkable that Zervos had the foresight to do this project from its inception, and then, later on in life, to continue it in the same format. He had this idea and this understanding of how to make it complete—the beginning has to feel like the end and it all has to fit together as one complete multivolume work. And then, you have volumes one through four that progress and they realized, by the time they got to the fifth volume, that it stood as a supplement to volumes one through four. They then picked up at volume six, moved forward, and added other supplements later on in the series of volumes.

SAZervos did amazing things. In the early 1930s he really took the time to go back to Greece and create his amazing books on the Cycladic art of Greece, as well as on Mesopotamian art, Sardinian art, and so on. For each book he organized a trip to visit the sites. He was completely immersed in the subject matter, and each time he came out with a new publication on these ancient civilizations, it was just more striking than the last.

DFEach volume of Cahiers d’Art was groundbreaking; he was presenting things that hadn’t been published before. He wasn’t just recycling other ideas.

SAHe also published architecture. He published Le Corbusier very early on. He published Russian architecture. He published Frank Lloyd Wright’s first monograph in French, which we are going to republish in English with Jean-Louis Cohen.

DFI think the incorporation of Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright and other architects into the fold of Picasso and other artists at the time is a very interesting combination.

I’m curious about your relationship to Cahiers d’Art. I know that your family was close with artists when you were growing up. Did you ever meet Zervos when you were younger, or did you have any introduction to Cahiers d’Art growing up?

SANo, I never met Zervos. I don’t think my father ever met him. We had the Zervos catalogue raisonné at home and we had many of the Cahiers d’art journals. So the imprint was familiar to me from my teenage years. But I never had the pleasure of meeting him nor had discussions about him with my father. Which is why it’s so strange how I stumbled onto acquiring the publication—I’m going to jump to how it happened, because you know, I bought Cahiers d’Art by accident.

DF[Laughs] I don’t know that you can buy something by accident.

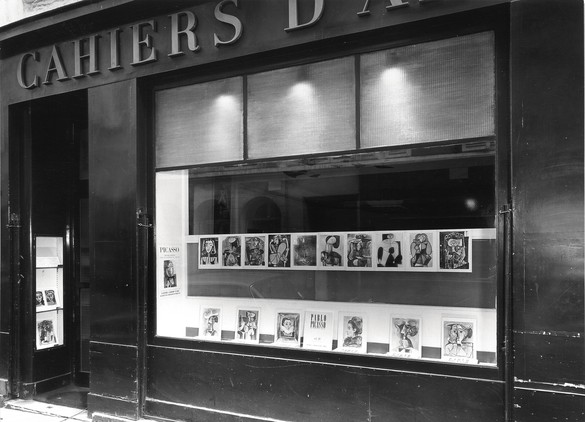

SAIt happened by accident, I promise. In 2010, I was walking my son to his friend’s house on rue de Dragon for a playdate. Right after I dropped him off, I turn around and I’m standing in front of Cahiers d’Art. I’d walked on the street a thousand times and I had never seen the imprint! Okay, I look and there’s a table with a bunch of old, great Cahiers d’art reviews on it. I see there’s a man sitting in the back. I decide to try to find out why they are open, because I know they’re not publishing much anymore or I would have seen it.

I ring the bell. I walk in and I change my question. Instead of asking this person why they’re open, I ask him who owns Cahiers d’Art today? He replies, “My brother.” I ask, “Would your brother sell it?”

He said that he didn’t know if his brother would sell because he couldn’t answer for him. I said, “Okay, here’s my card. Why don’t you ask your brother if he would have the kindness to call me?” And I walked out. The next day the brother called me. It was all a little surreal because there was no reason that I would ask that question and there was no reason that the brother would call me.

When I arrive, the brother who I first spoke to, Pierre de Fontbrune, lets me up the stairs and as I have my one foot on the upper floor, the other on the stairs, I see the brother upstairs, Yves, who is smiling. He says, “You’ve come at the right time. I was thinking of selling.” Like that. And as I put my last foot on the floor, I say, “Okay, I’ll buy it, but what do you have exactly?” And then he invited me in, he had two armchairs in the space and it was a wonderful room. There were all these books—it was very pleasant to sit there. Have you been?

DFYes, and I think at the time, Yves de Fontbrune was sitting at the same table that you describe [laughs].

SAYes, exactly. So that’s when he tells me his and his brother’s life story. Their father, Marc de Fontbrune, was Zervos’s secrétaire/manager from the end of World War II until past Zervos’s death. He stayed with Cahiers d’Art until 1976, when he retired, and Yves managed to get his father’s job. When he was twenty-seven years old, he became the new manager of Cahiers d’Art.

DFThey continued the business as a legacy business—not necessarily adding anything new to it, but just continuing to sell whatever stock they had on hand.

SAYes, they were a rare-book business, essentially. They became like a rare-books-and-prints shop, also selling catalogues raisonnés, plus they had an extra business, which was putting together complete sets of the Zervos and also assembling complete sets of the historical Cahiers d’art reviews, which were very valuable and sought after.

DF Yes, so they did add that piece; they developed the rare-book business, rather than just simply passively selling off everything.

So here we are, 2010, and you have the keys to the door. Where did the seed for republishing the Picasso catalogue raisonné, “Zervos: Picasso,” as we call it, idea come from? I mean, for you, was it just the natural thing to do: if you have ownership of this publishing house whose masterwork, if you will, is the catalogue raisonné of Picasso that’s been so inaccessible to so many, your desire to bring that to the market would be your first piece of work?

SAI was completely clear I wanted to restart the publishing house. The beauty was that nothing had been published since Zervos, besides one book, the Index général 1926–1960. That was a very helpful tool, the general index of the Cahiers d’Art publications sorted by authors, artists, and themes. But they had not restarted publishing books, only the occasional reprints. I wanted to relaunch the review. I thought that was essential. And obviously I wanted to republish the Picasso catalogue raisonné. My first priority was to try to put together the right people to work with me, because I’ve never published anything and I’m not from the museum or institutional world. I was very good friends with Sam Keller [director of the Fondation Beyeler, Riehen, Switzerland] and I like his intuitive intelligence. So I called Sam and he said, “Staffan, I don’t believe you [laughter]. It’s not possible.” I said, I agree it’s surreal, but it’s true. The reason I’m calling you is because I’d like to create a little think tank to brainstorm how to bring this imprint back to life. And he said, “Staffan, I’m in, 100 percent.”

He said, “I think you need an editorial team around you and I think we should bring in Hans Ulrich Obrist.” We ended up having dinner with him and Isabela Mora, who has worked with both Hans Ulrich and Sam for a long time.

DFSo they’re sort of the editorial board?

SAYes, we put together an editorial board and Sam and Hans Ulrich joined me as coeditors of the journal. And then we made a list of people we wanted to work with, sort of a dream list. The one artist we wanted to restart the review with was Ellsworth Kelly, because he had lived in Paris and we thought, Had Zervos gone to America, he would have loved Ellsworth Kelly in 1961. This was obviously a—

DFA pipe dream.

SA[Laughs] Yes, but we decided to try. Sam knew him because of the Beyeler.

DFYes, because they had an exhibition there, sure.

Our idea is to create the United Nations of catalogues raisonnés of important artists and architects. Cahiers d’Art, because of its legacy, prestige, and most important its neutrality—we don’t represent artists—would be like Geneva.

Staffan Ahrenberg

SABeyeler showed him and there were many important works at the foundation. So Sam called Ellsworth. And it was an immediate yes. He had been there in 1947, and explained how he had a few issues of Cahiers d’art in his possession.

This is how it started. Then we restarted the publishing house and the gallery, and created a new Cahiers d’Art team with Anya Bondell. We built a space across the street and it was slowly growing. The decision was to, at whatever cost, take our time to reestablish the brand and the publishing house at the highest quality with the best possible artists. In addition to republishing the Zervos catalogue raisonné, I wanted to continue making new catalogues raisonnés. It’s an absurd endeavor from a financial point of view, but I thought it was important as part of the brand. So I asked Ellsworth if he was doing a catalogue raisonné. He said he had been working on one for ten years but that it wasn’t ready. And I said, Do you have a publisher? He replied, “No, I haven’t thought of that.” I said, Would you consider Cahiers d’Art? There was a silence. I said, You would be next to Picasso.

We asked scholar Yve-Alain Bois to write the texts. Volume one was published in 2015 and won the Prix Pierre Daix, created by Christian Pinault. Unfortunately Ellsworth died shortly thereafter. We are continuing this precious collaboration with Jack Shear and the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation in Spencertown, New York. Then I met Frank Gehry through a very kind introduction by Maja Hoffmann while he was in Paris. We had the same conversation and he said, Yeah, this is my dream; of course I want to do it. I asked my friend the renowned architecture historian Jean-Louis Cohen to be the author.

The publication of the Kelly and the Gehry catalogues raisonnés inspired me to create the Cahiers d’Art Institute as a nonprofit in the United States. It’s a 501(c)(3). I’ve engaged Scott Stover as the executive director. He is American French and was responsible for the Centre Pompidou Foundation in Los Angeles, where he raised close to $50 million. He’s very knowledgeable about nonprofit structures in the art world. Our idea is to create the United Nations of catalogues raisonnés of important artists and architects. Cahiers d’Art, because of its legacy, prestige, and most important its neutrality—we don’t represent artists—would be like Geneva, to spin a metaphor. This has been formed and our plan is to hopefully get all the galleries to be patrons or users in one way or another.

DFWhat is it that you bring to the table? I mean, if they’re doing all the work, if they’re putting together the catalogue raisonné material anyway, what is the advantage of publishing it via the Cahiers d’Art Institute rather than either going to a commercial publisher or doing it in-house?

SASeveral. The future is online but in certain cases, subject to market demand, it will be published in book form. We are continuing to print the Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Gehry catalogues; over time they will be digitized to be accessed online at the Institute. Second: our new software upgrade in the making will have incredible search tools, and it will be anchored in the blockchain, which means that the data will be secure: if someone hacks into the system with a fake painting or work, it will be immediately known to the user. I think that is another major bonus.

The other advantage is, I would say, the legacy of the Cahiers d’Art brand. It’s attractive for artists, foundations, and galleries.

DFI think it’s fantastic. I would like to circle back to some of the things that we were talking about. I’m curious: what was Zervos’s editorial process in the late 1920s and early 1930s? Was it simply that he wanted to work with Picasso and would speak with Picasso, or were there other influences too?

SAIn practical terms, yes. The world was small and it was very Paris-centric. One contact led to another. Everyone was hanging out together. And he was serious about what he was doing, and had this ability to get things out at a very high level, intellectually and visually, which was very enticing for these people.

DFThe way he disseminated the review was through a subscription, which probably accounted for the majority of the sales, is that correct? They weren’t necessarily available for sale as individual copies, or were they?

SAIt’s a bit like today. He had subscribers and he had individual sales. And then of course he had sales at exhibitions of the featured artists. We could see in correspondence that when Picasso had an exhibition at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, there was a problem since Zervos wasn’t able to finish his publication on time.

I remember I found a very interesting letter Zervos had written. He was friendly with Alfred Barr [director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York], and he had written sort of a wish list to him. It said, If I could only have each member of MoMA as my subscriber, Cahiers d’art could come out in English. But it never happened. I mean, there were some books that came out in French and English, also in German. But I don’t even know that Zervos ever went to America. I don’t think he did. I don’t even know if he spoke English fluently.

DFThere are a lot of similarities in how you go about things compared to the model, if you will, that was set up. Do you feel beholden to Cahiers d’Art as a historical institution when you’re creating new works—that to do this under the imprint of Cahiers d’Art, it must reach certain standards, or are those more just self-imposed?

SAI do feel very beholden. I feel almost like I’m running with the Olympic torch. I have a responsibility. This is why I took it so slowly—I was lucky that we could afford not to pay so much attention to money in the first years and be able to create Cahiers d’Art basically without having a market for it. We could focus on the right mixture of quality: who the artists are, who writes, how we print it. I’ll give you an example, Taryn Simon’s book The Color of a Flea’s Eye: The Picture Collection [2020] took seven years. We took the time to do it right. I think we’ve managed step one here: we’ve managed to bring Cahiers d’Art back to life at the same level on which it began. In terms of Zervos’s editorial process, I have no comparison between myself and Zervos, because I don’t write, I’m not an art historian, I’m more of a producer, but in some ways we share aspects of artistic and graphic taste and other affinities. And, of course, I am working with a great team.

When we took over, in restarting the review, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Sam Keller, and I wanted to keep this dialogue going, like a metronome, between the contemporary art of the time of Zervos and the contemporary art of today, as well as working with historical art, like Goya, that will be celebrated in the next issue of Cahiers d’art. Because I think that is part of the DNA of Cahiers d’Art.