Sterling Ruby: The Frenetic Beat

Ester Coen meditates on the dynamism of Sterling Ruby’s recent projects, tracing parallels between these works and the histories of Futurism, Constructivism, and the avant-garde.

Winter 2018 Issue

On the occasion of Sterling Ruby: Ceramics, a traveling exhibition hosted at the Des Moines Art Center, Iowa, and the Museum of Arts and Design, New York, ceramics expert Garth Clark explores the artist’s practice, addressing the work’s allegiances and divergences from tradition.

Installation view, Sterling Ruby: Ceramics, Des Moines Art Center, Iowa, June 9–September 9, 2018. Photo: Rich Sanders

Installation view, Sterling Ruby: Ceramics, Des Moines Art Center, Iowa, June 9–September 9, 2018. Photo: Rich Sanders

The bloodiest of Sterling Ruby’s pots is not ceramic but a teacup of Styrofoam, urethane, wood, and spray paint. Monolithic, The Cup (2013) spilleth over with so much blood that one cannot believe the donor to this event will survive. And given the meanings that have been ascribed to this sculpture, that donor is mankind. Here, the character of ceramic vessels comes into play. A coffee cup would not have had impact—it is a beverage on the fly, informal, and does not suggest the finesse, civilization, ritual, and succor that tea does. As a result, the conceptual resonance is richer, more perverse, and humanized. While The Cup is a large work, even by the standards of Ruby’s bigger sculpture, it is not giant. Nonetheless, there is an impact on the viewer when a subject known for its intimate scale, four inches high in this case, explodes in size. The monumentality becomes greater than the sum of its measurements.

Several factors drew me to Ruby’s art. One was that his love for ceramics was not cocooned in a “special” place; his enthusiasm flowed and popped up into other aspects of his work, as, for example, in The Cup, his print Kiln #2 (2005), and the Debt Basin bronzes (2011–14). His ceramics themselves have roiled both the ceramics community and the art world. The 2014 Whitney Biennial featured three works from his Basin Theology series (2009– ); they were the most debated objects in the exhibition. Opinions depended on which planet one came from: the ceramics world has put Ruby up as a poster boy for the sloppy, mindless ceramics they see emerging from fine art; the fine-art world has largely been enthralled by his work. Indeed, New York Magazine critic Jerry Saltz, writing in the magazine’s online outlet Vulture, offered these “prehistoric-like wrecked giant ceramic ashtray-objects” as best in show.1

The impact of the ceramics community on the fine arts is negligible. Therefore, why even raise the issue? Because its influence is growing as more of its best are crossing over into art, and what ceramics can bring to the table should not be ignored. Fine art’s knowledge of ceramics, and of pottery in particular, is scant. Its critics often betray their poor understanding of the medium whether they write to praise or damn. Yet ceramics, over the last century, has produced an exceptional library of history and scholarship from which critics can learn. Some collaboration would benefit both sides.

Sterling Ruby, ASHTRAY 457, 2018, ceramic, 2 ½ × 16 ¼ × 14 ½ inches (6.4 × 41.3 × 36.8 cm)

My particular skill set has long been to walk the middle road between the two, and this essay seeks both to explain to the ceramics world how much they misunderstand about the importance of Ruby’s work and to highlight how much the art world has yet to learn about a complex medium. One often hears of ceramics being a “recent” medium for Ruby—code for untutored mishaps. Not true. His direct studio involvement stretches back over twenty years, when he enrolled in a ceramics class to test the belief that working with clay could be a therapeutic tool. What struck him was that his fellow classmates “were not artists,” and so there was an innocence to making. Ruby did not intend ceramics as a career path but remembers, “I became fascinated with the fact that very different people were making the same type of biomorphic and anthropomorphic work. A lot of it was sexual, with holes, extensions, and everything overly glazed. Clay does give people an innate and unfettered sensibility. I loved it.”2

Ruby’s connection goes back even further. As a child, his family moved from Germany (his father was in the American military) to a farm near New Freedom, Pennsylvania, in the heart of the Pennsylvania Dutch craftland. His Dutch mother collected ceramics, so the pot had its place as an objet de vertu in his early life; so did quilting.

Ruby initially took a conceptual approach in working with clay: “I first thought of my early ceramic works as sociological and psychological studies, case studies in art therapy. But over time I have come to see and embrace their strong connection to craft.”3 This interest came when the medium was still verboten; he recognized that artists of his age were not working in ceramics. He recalls,

At that time, clay was seen as craft, not conceptual. Handmade objects were associated with gesture and sincerity, and many artists my age had no interest in those things; most artists were grappling with the fallout from postmodernism and conceptual art.

To be an instinctive artist was completely at odds with how I was taught. My generation was told to have a premeditated concept, an already answered theoretical question before making anything. Using clay became a way to just make something; it represented the gesture I was longing for.

I started to see my ceramics as monuments to my desire to make a sincere gesture, and the shame that came with it. So now, 15–20 years later, ceramics represent that transition for me. It might also mean that a younger generation of artists who don’t have the same hang-ups that I did can readily use the material for what it is, just making vessels, ashtrays, dishware, figurines.4

Sterling Ruby, Basin Theology/The Pipe, 2013, ceramic, 39 ¾ × 43 ½ × 44 inches (101 × 110.5 × 111.8 cm)

That is what he made: ubiquitous domestic items, bread baskets, ashtrays, basins. In some cases the technique seems rudimentary, particularly in the ashtrays, which perhaps more closely resemble pizza pie 101. And this is where part of the problem emerges.

High-skill makers (not just ceramists) experience anxiety when they see prominence being given to a work that is to their way of thinking inept. That threatens the pillar of their aesthetic. “There’s a misalignment of what signifies ‘amateur,’” says Garth Johnson of the Ceramic Research Center at Arizona State University, Tempe. “The general public sees lumpy, lopsided, gestural work, and it communicates lack of craftsmanship, when in fact, true beginner work always strives for perfection and winds up mired in that struggle.” The judgment is usually “That is the best they can do,” not understanding that taking on the amateur can be an aesthetic choice, not a technical one, to deny the medium the preciousness of High Craft.5

The ceramics are wet, their surfaces resembling blood, mucous, or the iridescent shimmer that one sees on large slabs of meat.

Garth Clark

This ploy, essentially faux humility employed to make a point, has been used in the United States by George E. Ohr (1857–1918), the visionary potter from the turn of the last century; by Peter Voulkos, in his revolutionary application of abstract expression to ceramics; and by the California Funk master Robert Arneson, who famously had inscribed on his car’s license plate the legend “Ceramics is the world’s favorite hobby.”

Of all Ruby’s vessel series, it is Basin Theology that is the most powerful. It is instructive to hear what the artist himself said in 2015 about the intent of this work:

I have been making large ceramic basins and filling them with broken materials that look like animal remains and architectural waste. I am smashing all of my previous attempts, and futile, contemporary gestures, and placing them into a mortar, and grinding them down with a blunt pestle. I am doing this as a way of releasing a certain guilt. If I put all of these remnants into a basin, and it gets taken away from me, then I am no longer responsible for all my misdirected efforts. I will no longer have to be burdened with the heaviness of this realization. This is my Basin Theology.6

Sterling Ruby, Basin Theology/SACRUM SACRAL, 2017, ceramic, 20 × 66 × 43 inches (50.8 × 167.6 × 109.2 cm)

Before exploring this further, it is helpful to look at a sister series, Debt Basins, and at a unique work, Excavator Dig Site (2010). These works are in bronze, but to use a biblical metaphor, they are “born of clay.” To make a point that is poorly understood, clay and ceramics are not the same practice. Clay is a natural material. Our intervention of firing it turns it into a completely new compound, ceramic, and the clay is lost. Ceramic is mankind’s first synthetic material (traditional potters loathe that point). In essence, it is the same pairing as oil (natural) and plastic (synthetic).

Working with unfired clay has become big in contemporary sculpture, with Adrian Villar Rojas, Mark Manders, Anna Maria Maiolino, and Urs Fischer among the major practitioners. In this we see the difference between the Basin Theology and the bronze Debt Basin series. The latter metaphorically evokes archaeology more literally and potently; one can imagine a Mesopotamian dig in the desert revealing, among other materials, unglazed ceramic objects.

To quote Ruby, “The positives are made primarily from clay, along with added scrap of metal, wood, foam, etc. Once they are sculpted, they are then molded and cast in bronze using a lost-wax technique.”7 Both the textural sensitivity of the casting and the patina choice emulate their source. And in this work, we see Ruby’s affection for the ceramics of Peter Voulkos; Ruby echoes the power of that artist’s last works, wood-fired wall platters. As to the meaning of “debt,” Ruby offered this insight: “What does one owe history? The history of art, the history of oneself (autobiography), the history of the objects that fill the basin (salvage).”8

The impact of Basin Theology is surprisingly different from that of Debt Basins considering that they have a similar metaphoric root in archaeology. The elements are more architectural in the latter and more organic in the former. For me, embracing the works was no problem, but there was difficulty in adding the archaeology tag. And this is where I get back to bloody pots. They are not just “muscular” but look like slabs of muscle, too big for a human—horses, maybe. When the New York Times critic Roberta Smith saw these “obstreperous ceramics” for the first time, her take was that they contained charred animal remains.9

Sterling Ruby, Basin Theology/Pentedrone, 2014, ceramic, 39 × 46 ½ × 44 ¼ inches (99.1 × 118.1 × 112.4 cm)

Why not the same fleshiness for Debt? In part, it is because the bronzes are texturally dry. The ceramics are wet, their surfaces resembling blood, mucous, or the iridescent shimmer that one sees on large slabs of meat. This sense is exaggerated or reduced depending upon the color or type of glaze, but it never goes away. Even Basin Theology/HATRA, though blue-black, has the light gloss and soft quiver of liver.

This association is not new. One of the great Chinese glazes from the Ming Dynasty was a copper red known variously as sang de boeuf (ox blood), flambé, and, when it tends toward the blue side, horse’s liver. Ruby takes it much further; the red glazes drip, spread, pool, and coagulate all over his form. The interior contains the artist’s history of feeling, making, projecting, leaving behind detritus, some digested and now formless, some partially digested, and some resolutely indigestible and indestructible. The scale and gravitas—these works weigh a few hundred pounds—confront the viewer with mass and volume that border on violence. Not a minor achievement for a pot—or any artwork, for that matter.

Installation view, Sterling Ruby: Ceramics, Des Moines Art Center, Iowa, June 9–September 9, 2018. Photo: Rich Sanders

Ruby invited me to visit his Los Angeles studio in June 2017 to choose works for the Regarding George Ohr show.10 His studio manager took me on a tour of many departments within his four-acre space and its 120,000-square-foot building. In each department, a staff of specialists managed that specialty: big paintings, small paintings, textiles, metal sculpture, and so on. Finally, we got to the ceramics and I met the man I assumed to be Ruby’s clay guy. Thirty minutes flashed by as we talked, and I was impressed that Ruby had found someone with such a passionate feeling for the medium, so much knowledge, and who saw the big picture, wittily skewering the fine-arts/ceramic reticence, and was so sly in understanding the vast ceramics community and Ruby’s contested status within that world. The conversation was electric yet I knew I had yet to meet the maestro himself. As I was turning away, reluctantly, to move on, I asked, “What is your name?” “Sterling Ruby,” he replied.

1 Jerry Saltz, “Seeing Out Loud: There’s a Smart Show Struggling to Get Out of This Big, Bland Whitney Biennial.” Available online at www.vulture.com/2014/03/jerry-saltz-on-the-whitney-biennial.html (accessed August 2018).

2 “Sterling Ruby—Why I Create,” September 2017. Available online at http://www.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2017/september/12/why-i-create-sterling-ruby/ (accessed August 2018).

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Garth Johnson, quoted in Sarah Archer, “The Meaning of Clay at the Whitney Biennial,” Hyperallergic, April 24, 2014. Available online at https://hyperallergic.com/122270/the-meaning-of-clay-at-the-whitney-biennial/ (accessed August 2018).

6 Ruby, “American Perspectives,” quoted in Alessandro Rabottini, Permanent Mimesis: An Exhibition about Simulation and Realism, exh. cat. (Milan: Mondadori Electa, 2010, for GAM—Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Torino, Turin).

7 Ruby, quoted in Tyler Britt, email to the author, January 29, 2018.

8 Ibid.

9 Roberta Smith, “Art in Review: Sterling Ruby,” New York Times, March 21, 2008. Available online at www.nytimes.com/2008/03/21/arts/design/21gall.html (accessed August 2018).

10 Regarding George Ohr: Contemporary Ceramics in the Spirit of the Mad Potter, Boca Raton Museum of Art, November 7, 2017–April 8, 2018.

This essay was commissioned and published by the Des Moines Art Center in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Sterling Ruby: Ceramics; artwork © Sterling Ruby; photos: Robert Wedemeyer unless otherwise noted

Garth Clark is the leading scholar and critic on modern and contemporary ceramics, with over ninety books and writings to his credit. He is currently completing Mind Mud: The Conceptual Ceramics of Ai Weiwei and Lucio Fontana Ceramics. He has earned many awards and honors, including the College Art Association’s Frank Jewett Mather Award. He is a Fellow of the Royal College of Art, London.

Ester Coen meditates on the dynamism of Sterling Ruby’s recent projects, tracing parallels between these works and the histories of Futurism, Constructivism, and the avant-garde.

Join Sterling Ruby in his Los Angeles studio as he works on new abstract paintings ahead of his exhibition TURBINES at Gagosian in New York.

As spring approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, Sydney Stutterheim reflects on the iconography and symbolism of the season in art both past and present.

Alessandro Rabottini investigates the theoretical and formal underpinnings of Sterling Ruby’s career through the lens of the artist’s series ACTS.

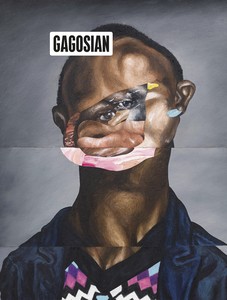

The Fall 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Sinking (2019) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn on its cover.

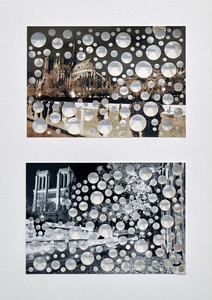

An exhibition at Gagosian, Paris, is raising funds to aid in the reconstruction of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris following the devastating fire of April 2019. Gagosian directors Serena Cattaneo Adorno and Jean-Olivier Després spoke to Jennifer Knox White about the generous response of artists and others, and what the restoration of this iconic structure means across the world.

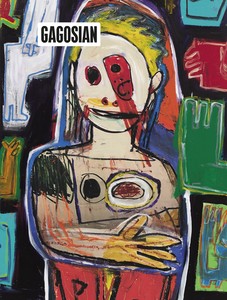

The Winter 2018 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available. Our cover this issue comes from High Times, a new body of work by Richard Prince.

Mario Codognato, curator of the exhibition, discusses Sterling Ruby’s first-ever European survey, at the Belvedere’s Winterpalais galleries.

David Cronenberg’s film The Shrouds made its debut at the 77th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in France. Film writer Miriam Bale reports on the motifs and questions that make up this latest addition to the auteur’s singular body of work.

Alison McDonald celebrates the life of curator Richard Marshall.

Alice Godwin and Alison McDonald explore the history of Roy Lichtenstein’s mural of 1989, contextualizing the work among the artist’s other mural projects and reaching back to its inspiration: the Bauhaus Stairway painting of 1932 by the German artist Oskar Schlemmer.

The mind behind some of the most legendary pop stars of the 1980s and ’90s, including Grace Jones, Pet Shop Boys, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Yes, and the Buggles, produced one of the music industry’s most unexpected and enjoyable recent memoirs: Trevor Horn: Adventures in Modern Recording. From ABC to ZTT. Young Kim reports on the elements that make the book, and Horn’s life, such a treasure to engage with.