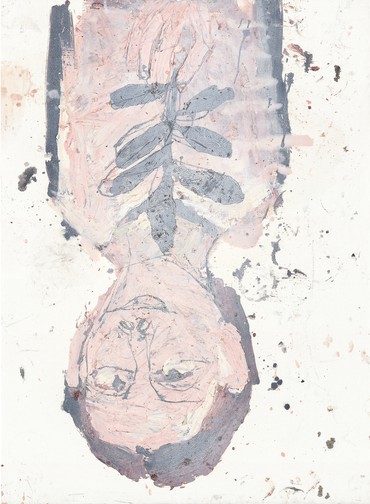

The German painter, printmaker, and sculptor Georg Baselitz is a pioneering postwar artist who rejected abstraction in favor of recognizable subject matter, deliberately employing a raw style of rendering and a heightened palette in order to convey direct emotion. Photo: Elke Baselitz

Sir Norman Rosenthal is an independent curator and art historian. After a short time spent as exhibitions officer at Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, and subsequently as curator at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, in 1977 he became Exhibitions Secretary at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, where he remained until 2008.

Norman Rosenthal You call the exhibition Devotion. That means a lot, or maybe not?

Georg Baselitz To me it simply means paying respect, in this case to quite specific people, artists I admire. They all have to do with my painting.

NR How did these works come about?

GB For that I have to explain that I don’t make anything out of thin air. I always have sources, I always use information from the past. So in Basel I saw a famous picture by Henri Rousseau showing Guillaume Apollinaire with his muse, the painter Marie Laurencin. Mistakenly, I thought the subjects were Rousseau and his wife—that it was a self-portrait with Mme. Rousseau. Picasso owned a Rousseau self-portrait and a portrait of his wife, and Franz Marc copied a Rousseau self-portrait for the Blaue Reiter. At first I wanted to paint [my wife] Elke and myself as M. and Mme. Rousseau, just as I’ve often done similarly—Elke and me as the parents of Otto Dix, and so on. But that didn’t turn out, so I began again—altogether classical, straightforward, simply with the Rousseau self-portrait and his portrait of his wife. Then I found this book from the 1930s, 500 Selbstportraits (500 self-portraits), and so it took its course.

NR So are these new paintings all based on self-portraits of artists?

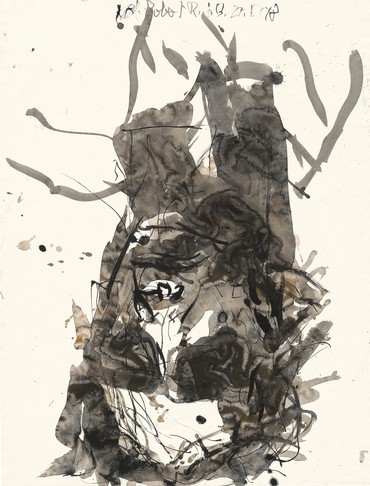

GB Yes, it’s important to note that I didn’t paint portraits of anyone, I painted their self-portraits. Earlier on, I also worked from portraits—think of the [Ferdinand von] Rayski heads, [Winfried] Dierske, and then there were [Marcel] Duchamp and [Ernst Ludwig] Kirchner and [Erich] Heckel—never from life but from history, from art.

NR But the new portraits are all related to your first ones from 1969?

GB Yes, the ’69 pictures. Back then it was a matter of demonstrating the upside-down method. There have been portraits throughout art history, but afterwards, in my opinion, it is the painter who has always been more evident than the subject. At that time I painted portraits in a wholly matter-of-fact style, perfectly prosaically, with no artistic additions. And the people were familiar to me—my wife, a few friends like Franz Dahlem, and so on. It was solely about the upside-down method. These new pictures are also a demonstration: I call the exhibition Devotion, the people portrayed are important, and unlike before, one definitely recognizes a style.

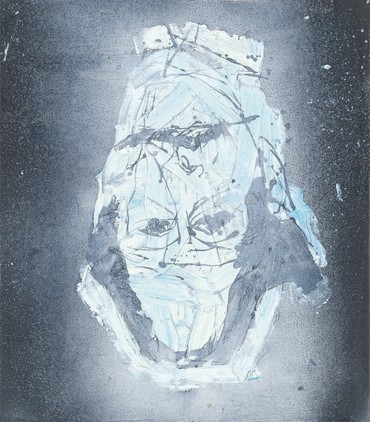

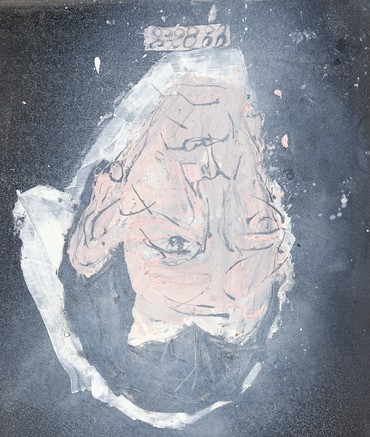

NR It’s almost as if the pictures were displayed in a pantheon. If they were sculptures they’d be on pedestals.

GB Exactly. Nearly all of them are painted on a black ground, and the painting is applied on top of it. Against this black ground I make a tightly composed form, a head shape in a very light color, the internal drawing of the portrait, and that’s it. It’s an application, not painting based on form. The whole thing is disembodied, shadowless, spaceless.

NR The heads float.

GB Precisely. In these pictures I pursued the principle that the head floats, without a pedestal. It isn’t a photograph: when you take a photo you always get everything else, the space, the form, the shadow, even details about the subject that place the portrait in time. All that is missing in these works.

NR The pictures most remind me of your Abgarköpfe [Abgar Heads, 1984].

GB You know the story behind the Abgarköpfe? Abgar was this king who wanted a picture of Jesus, because the plague was raging in his city and he’d heard that Christ performed miracles. So he sent a messenger, the messenger told Jesus what the king wanted, and Jesus took a cloth and held it against his face.

NR A charming legend, and your portraits look like these Jesus cloths. Can one think of your pictures as somewhat like Veronica’s veil?

GB You could. I hadn’t thought of that, but yes, you could compare them.

NR Do you feel that art is the religion of today? Or is it a kind of religion for you?

GB Art is the most interesting thing there is, and religion does not interest me. Art is what occupies me, what I believe in. That’s proven to me whenever I enter a museum. Sure, I might see a Crucifixion or a Resurrection there, but it has never occurred to me to look away. I’ve always felt, Aha! That’s such and such and it was painted by so and so.

NR But are the portraits also about personality? Or about similarity to the subject? Should viewers recognize the person portrayed?

GB Of course they’re about similarity, and I’d be happy if viewers recognized the subject, but I’m sure that’s hard. When I look at them I immediately see that this one is Dix, that one [Arnold] Schoenberg, that one [Tracey] Emin—that each is a portrait of someone. That should actually be enough. If the thing is painted upside down, it doesn’t matter whether you make it a likeness or not. I have nothing to do with photorealism. If you paint a portrait after a self-portrait and upside down, it has to be okay. That’s an additional point, or an exclamation point, about that way of working. I don’t know of anything in the world of painting to compare with it.

NR So these new pictures aren’t simply musings or fantasies, like your early heroes?

GB No, no. I’ve done my research, I’ve worked with these since the spring of 2018, and there are photos of the self-portraits all over the place.

NR You had photos as patterns for all of the portraits?

GB Photos of self-portraits. They’re all exclusively self-portraits by the artists pictured. That wasn’t always easy. Lucio Fontana, for example, is difficult, but there was an edition of his letters, Lettere 1919–1968, with a self-portrait drawing on the cover from the ’30s or ’40s, in any case very early. I’d like to have had a self-portrait of Alberto Burri but there’s only an abstract picture, with a sort of window and another window, that he calls a self-portrait. I couldn’t do anything with that, unfortunately. It got really amusing, for example, with this strange picture of Nicole Eisenman: I found three self-portraits of hers that you can’t recognize as one and the same person, because all three look so different. In one she’s a masculine type, in another a Bavarian type with a peaked and feathered hat, as if painted in the ’30s, and in a third she looks like a fifteen-year-old boy. And they’re all Nicole Eisenman self-portraits. When I looked at them that way I thought, This reminds me of Die Frau mit der Handtasche (Woman with a Bag), by [Karl] Schmidt-Rottluff, a famous picture from the 1910s, I believe. I mixed all of that up in my head, and that’s how I produced this portrait of Nicole Eisenman. That’s how almost all of them were produced.

Clyfford Still was another—I didn’t know any self-portraits of his, I only knew his paintings, and found them wonderful. Then I did some research and found three self-portraits from his student years, when he was still quite young, before he became an Abstract Expressionist. That’s how it was with other artists I worked on whom I admire—[Roy] Lichtenstein, [Piet] Mondrian, [Andy] Warhol . . . all those are from early self-portraits when they were young. I first had to become familiar with these pictures, because they’re academic. With [Robert] Rauschenberg it was a little difficult, because the only Rauschenberg self-portraits are photos in his collages that he declared to be art. So those are what I painted.

religion does not interest me. Art is what occupies me, what I believe in. That’s proven to me whenever I enter a museum.

Georg Baselitz

NR The pictures represent your personal heroes, you have said, but Lichtenstein, for example, is an artist with whom I would never have associated you.

GB Yet he’s wonderful. I have pictures of his in my collection. They’re fantastic pictures. And there’s a self-portrait that’s really strange, where he painted himself with a bowler hat and a very stern gaze, perhaps at seventeen or eighteen.

NR Alexei Jawlensky isn’t included—why is that?

GB Don’t ask me. There’s no justice.

NR The selection is curious, I have to say, but is that coincidental or, as John Cage would say, a matter of chance?

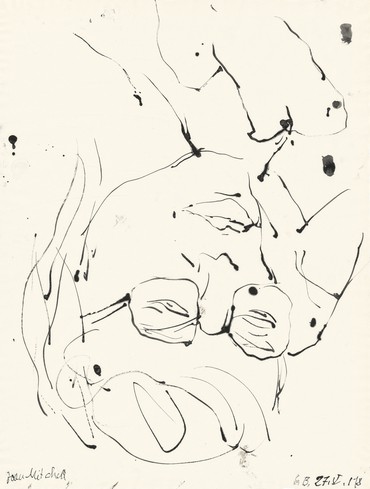

GB It’s both. Take the women painters, for example: there’s Joan Mitchell. With her what happened was, I saw a painting of hers in a magazine and next to it a photo of her. I didn’t know anything about Joan Mitchell and I’d thought she was a man. Then there was this interview in which I came out looking like a misogynist, because it was felt that I only found a woman painter good because I thought she was a man.

Tracey Emin—there’s this strange Dutch television series by her that I didn’t know at first, but then I was told that in this series I marry Tracey Emin, or she marries me. All these stories and relationships play a role in these pictures. But basically the main theme is my engagement with art, from the Mannerists to the present. And lately I’ve been greatly engaged with the art of women. This malicious criticism that I dismiss art by women is nonsense. I’ve only provoked it a bit.

NR One of the artists is Frank Auerbach—how did you happen on him?

GB That’s a long story. When I saw the first Lucian Freud retrospective at Berlin’s Nationalgalerie thirty years ago, I found it completely uninteresting. In Berlin, a Berlin painter? I felt it was historical, conservative painting from Berlin. Then later I read [W. G.] Sebald, and he has a long story about Auerbach. There he’s called Max Ferber. And then I wondered: why is the London School—Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, and so on—so terribly conservative, although they behave like avant-gardists? But it was very different. What Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud, and Leon Kossoff made was Berlin painting from the ’30s. Just the same. In Berlin there was a painter called Otto Nagel, he’s not so interesting today but he was very important at the time and painted scenes from the lives of the proletariat. And the pictures by these three London School painters always remind me of him. What Auerbach makes is by no means English art. It’s called London School because that’s where it’s made. All that is okay, but essentially it’s German painting.

NR Auerbach is still working. He paints, just like you, every day. I have the feeling that you too work every day. The difference is that you also make sculpture and he doesn’t. You have a lot of things in common. You’re both radical conservatives. Could one say that?

GB But the word “conservative” is of course misused. If you want to make somebody look bad, repulsive, you say he’s conservative. Not avant-garde, not progressive.

NR You’re conservative and progressive at the same time.

GB If you say so . . .

NR To what extent do your new pictures have to do with memories?

GB A great deal, of course. Take for example Clyfford Still. In 1975 I went to Marlborough in New York, with Kaspar König as translator, and we said, “Please show us a picture by Clyfford Still.” Then he showed us a wonderful Clyfford Still; I think at the time it cost $40,000. That must have been a lot of money back then. Kaspar König later bought the picture and sold it to the museum in Cologne.

Later I asked Johannes Gachnang, director of the Kunsthalle Bern, to produce a Clyfford Still exhibition. He went to Still, somewhere in the American hinterland, and heard all his grievances. But Gachnang brought back some informative materials that explained certain things to me. Only then did I learn that there were artists who painted after these pattern books you could buy in art-supply stores, the way I paint still lifes, the way I paint a portrait, the way I paint a nude. And that’s just what Clyfford Still did, that was his training when he was young. I found that impressive, of course, to this day. So I refreshed my memory.

This demonstrative impulse, this audacity, this love of display—the whole of American society was like that. . . . Meanwhile all we were thinking about in Germany after the war was how to get out of our mess.

Georg Baselitz

NR Jackson Pollock is also one of your heroes.

GB There was a show with a small self-portrait by Pollock, really quite small, and in it he looks like a Mexican boy. Next to it hung the little self-portrait by [Mark] Rothko. There are no self-portraits by these two except these.

NR What is it that fascinates you about Pollock?

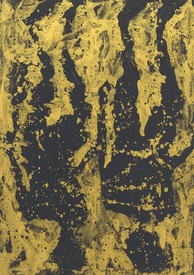

GB Well, the New York School was such a big thing; these pictures had such presence. They weren’t painted as a provocation, they were simply there. In America there were young people who saw what was being made there, the miserable, retrograde art that existed there, as though in the backwoods, and these young people were inspired by the Europeans—by Existentialism and all these revolutions, above all Surrealism. Almost all of these artists began as Surrealists, they were regular proselytizers for Surrealism there in New York. And then they had such audacity: first of all their formats, these commanding formats, gigantic. Think of Pollock. As students in Berlin we could only shake our heads. We could barely afford ten centimeters of canvas and here comes somebody who makes paintings ten meters long and five meters tall. This demonstrative impulse, this audacity, this love of display—the whole of American society was like that, everything that was happening. Meanwhile all we were thinking about in Germany after the war was how to get out of our mess.

NR Is that also true of Alexander Calder? Fontana I understand, but I wouldn’t have expected Calder from you.

GB In my mind you can put Calder right next to Clyfford Still. In a wonderful way, he broke through the limitations sculptors imposed on themselves, or that were prescribed by their materials. He simply presented trees with leaves, more or less. That is magnificent. And he did it with such playfulness. I find that terrific. I get inspired when I see these things. Calder invented a kind of abstraction for sculptors that is simply fantastic. Like Pollock in painting. Awesome.

NR Your cosmos also includes painters almost unknown in America, such as the German tachist Wols. Why is he important to you?

GB When I came to West Berlin in 1958, Wols was almost the first thing I saw. That was at Rudolf Springer’s, the city’s most respected gallery at the time. Then alongside him there was Gerhard Hoehme, who imitated him, and many others who also made imitations. They’re all like Wols: they painted a center filled with diverse things. And what’s the problem in this whole art circus, why didn’t that have any lasting success? It was simply the format. It’s as if you tried to make a philosophy, a worldview, a reality. The “Informel,” the “École de Paris”—that doesn’t work on the art market. The art market is something all its own.

NR Even Warhol was almost forgotten on the art market shortly after his death, and prices were low. Then suddenly he became the most important artist of all, and also the most expensive. You also drew his self-portrait.

GB Warhol is truly a phenomenon. I’ve seen these thousands of drawings that he made—it’s phenomenal, this mad, mad industriousness. You think he’s doing nothing, he’s only pretending, and then these fabulous pictures appear.

NR But Warhol’s method is totally different from yours.

GB He’s American, full-blooded American. But in approach, completely international.

NR He had a giant studio, many assistants, like Damien Hirst and others. To this day you do everything yourself.

GB I would say that for me that’s wholly explained by my biography. Germany wasn’t America, Germany wasn’t Paris, Germany was simply in an altogether crappy situation. I don’t know of a single German artist of that time who worked like an American. There weren’t any.

NR But now it’s nearly 2020, seventy years after the war. How do you see the world of painting today? Is what you’re showing here a reflection?

GB I think so. I wouldn’t say that it’s the reflection of an old man, either. I would say it’s the reflection of European art on art in general, America included.

NR Does Europe still have a future aesthetically?

GB Absolutely. We still have some life in us. There are still these half-baked, idealistic, crazy things coming out of Europe, these diffuse things lurking around in the universities, people’s heads. They’re still coming out of Europe.

NR Still?

GB Still. The practice in America, I call it Hollywood. That kind of entertainment is no longer predominant in Europe, it’s long past. But the stimuli come from here.

NR When we started talking we compared this series of self-portraits with the Jesus cloths. Might one say that Tracey Emin, Cecily Brown, Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol, and all the others are your patron saints?

GB It’s my prayer niche. My home altar.

NR But many well-known artists who have engaged you we don’t find among the new paintings and drawings.

GB It is what it is, that’s not a flaw. I can pay homage to the whole world without painting it.

Georg Baselitz: Devotion, Gagosian, West 24th Street, New York, January 24–March 23, 2019

Artwork © Georg Baselitz; photos: Jochen Littkemann unless otherwise noted

![Georg Baselitz, Ohne Titel (nach Pontormo) (Untitled [after Pontormo]), 1961.](https://gagosian.com/media/images/quarterly/essay-baselitz-bildung/qxhewJId3rEi_275x275.jpg)