Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

An enormous eagle, wings outstretched against a turbulent sky, talons drawn as if about to pounce, confronts the visitor halfway through this exhibition of sixty years of protean output by Georg Baselitz—except that the eagle is painted upside down and, as the label informs us, painted not with a brush but with the artist’s fingers.

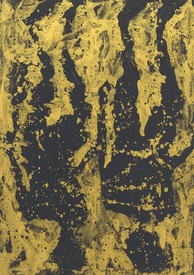

Inverting the subject and painting with his fingers are just two of the strategies that Baselitz has adopted in order to draw our attention to painting’s status as a self-contained object rather than a record of perceived reality, leaving us free to concentrate on painterly values. These and other techniques, such as painting on the floor, also help him to avoid falling into the trap of creating works that are too elegant, harmonious, finished. Much of his art, whether paintings, drawings, prints, or sculpture, has a rough, spontaneous quality that appeals directly to our instincts.

In the context of German history, the eagle is of course a loaded motif—a symbol of Prussian imperialism, later appropriated by the Nazis. But by painting the creature upside down as well as with his fingers, in this and other paintings from 1972, Baselitz drains it of its political connotations. The expressive brushwork of Jasper Johns’s numerous renderings of the American flag performs a similar, neutralizing function. Both artists reintroduced figurative imagery into contemporary art at a time when abstraction was preeminent (Abstract Expressionism in the United States; Tachism, its watered-down variant, in France and Germany). Both questioned the role of art, believing it to be open to multiple interpretations rather than tied to a single meaning. Baselitz in particular is skeptical that art should communicate a message at all, having witnessed art’s misuse by two totalitarian regimes—National Socialism and East German communism—for propagandist ends. His guiding principle has been to “unlearn” what he has been enjoined to think, in art as much as in education or politics.

Baselitz’s belief in art’s autonomy, and that the artist is fundamentally “asocial . . . with nothing to say,”1 evolved slowly. Throughout the 1960s, unlike most other German artists of his generation, he was preoccupied with exploring what it meant to be a German artist in a defeated Germany—“a destroyed order, a destroyed landscape, a destroyed people, a destroyed society.”2 At school in East Germany, he had been kept ignorant of the Holocaust and was largely unaware of the concentration camp system. It was not until he crossed over to West Berlin in 1957, having been expelled by the Hochschule für Bildende und Angewandte Kunst in East Berlin for “sociopolitical immaturity,” that the gaps in his knowledge of recent German history were gradually filled. He saw a German-language version of Alain Resnais’s 1956 documentary about the Holocaust, Nuit et brouillard (Night and Fog), and followed the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem through news reports. He later reflected: “Most people got over things by not looking at them or by denying them. . . . the terrible, rotten, unbearable time in Germany between 1933 and 1945. I’d been engulfed in all that.”3 His father, Johannes Kern, a village schoolteacher and member of the Nazi party, had been conscripted into the Wehrmacht in 1939 and took part in the invasion of Poland. In 1961, wishing to dissociate himself from his father, Baselitz changed his surname from Kern to Baselitz, after the village in eastern Germany (Deutschbaselitz) where he had spent the happiest of childhoods, in spite of severe deprivation in the immediate postwar years. Following the construction of the Berlin Wall, also in 1961, he felt cruelly cut off from his roots.

Baselitz’s paintings and drawings of the early 1960s are populated with dehumanized groups of naked, diseased figures and dismembered body parts. The first room in the Pompidou is dominated by eleven paintings, all a meter or more in height, each depicting a truncated foot: putrid stumps, swollen and discolored in appearance, implying suffering and death. In the same space hang the two paintings that were confiscated by the police on the grounds of obscenity from Baselitz’s first solo exhibition in West Berlin in 1963: Der nackte Mann (The Naked Man, 1962) and the larger Die große Nacht im Eimer (The Big Night Down the Drain, 1962–63). Each shows a naked or seminaked male figure, one lying, the other standing, painted in sludge-like colors that suggest decomposing flesh, gripping an oversized erect penis in a gesture of futility and despair. Less abject but equally provocative were the ironically named Helden (Hero) paintings that followed in 1965. These wounded, bedraggled figures dressed in torn battledress, staggering barefoot across devastated landscapes—the conquered “master race” returning from captivity—were a painful reminder to West Germans enjoying the fruits of Ludwig Erhard’s “economic miracle” of truths they would rather have forgotten.

The most exuberant section in the exhibition is that devoted to the 1980s. This was a period of sustained creativity that saw Baselitz paying homage to the late self-portraits of Edvard Munch, the chromatic richness of Emil Nolde, and the group portraits of the Brücke—exactly the sort of art that had been denounced as “degenerate” by Hitler. Loosely, even aggressively, painted in a palette of raw yellow, orange, ox blood, and black, these dramatic figure paintings combine the “primitivism” of the German Expressionists with the expansive scale of Abstract Expressionism. Baselitz may also have been responding to the “wild” paintings of a younger generation, the so-called Jungen Wilden (“young savages”) in Germany and their Neo-Expressionist cousins abroad, who regarded him as their spiritual father.

Women are the ostensible subjects of a large number of Baselitz’s figure paintings. Absent from this exhibition are both of his monumental, multipartite cycles that portray women: Strassenbild (Street Picture, 1979–80) and ’45 (1989), which obliquely commemorates the destruction of Dresden in 1945. However, this is compensated for by the inclusion of two smaller groups of work: three sculptures from Baselitz’s Dresdner Frauen (Women of Dresden) series—large heads, carved and gouged out of various woods and painted cadmium yellow, that evoke the resilient survivors of the bombing who cleared the historic city of rubble—and a handful of unsparing double portraits from the last decade showing the artist with Elke, his wife of sixty years, seated and naked, in a pose recalling Otto Dix’s celebrated portrait of his aging parents. Now that the German historical context has receded from his practice, Baselitz’s art speaks poignantly of mortality and enduring love.

1Georg Baselitz, Collected Writings and Interviews, ed. Detlev Gretenkort (London: Ridinghouse, 2010), pp. 209, 213.

2Ibid., p. 245.

3“Georg Baselitz in Dialogue with Martin Schwander,” in Baselitz, exh. cat. (Riehen/Basel: Fondation Beyeler; Washington, DC: Hirshhorn, Smithsonian Institution, 2018), p. 46.

Artwork © Georg Baselitz 2022

Baselitz: La rétrospective, Centre Pompidou, Paris, October 20, 2021–March 7, 2022

![Georg Baselitz, Ohne Titel (nach Pontormo) (Untitled [after Pontormo]), 1961.](https://gagosian.com/media/images/quarterly/essay-baselitz-bildung/qxhewJId3rEi_275x275.jpg)