Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

Georg Baselitz doesn’t stand still. His capacity for hard work and his inexhaustible energy are remarkable for an artist in his eighties, especially one who paints crouched over the floor, bent double. Last summer he started experimenting with an entirely new technique. This is best described as a process of transferring an image from a painted canvas lying unstretched on the floor, the oil paint still wet, to a second canvas laid over it, covered with either a white or a black ground. Baselitz then applies various degrees of pressure to the back of this second canvas. Once it has been peeled away from the first canvas, the latter is usually discarded, though occasionally it is worked on and exhibited in its own right.

The transfer differs from the original in that it is a mirror image, reversed as in printmaking. Some of the first works on a black ground produced in this way were given a coating of gold paint mixed with gold varnish, either through a spray pump or with a brush or both. Others, including those in a San Francisco exhibition this spring and in a second body of work to be shown in Hong Kong, have not been directly touched by the artist’s hand.1

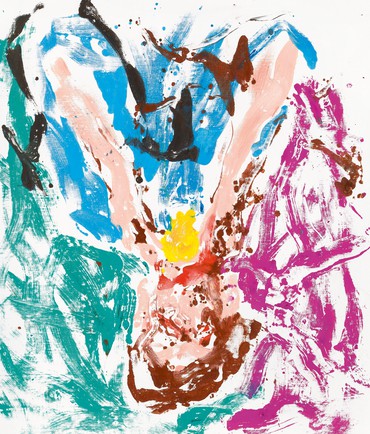

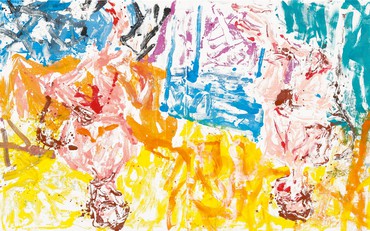

The two shows could not be more different but they are in a striking sense complementary. The San Francisco paintings, a riot of acidic colors on white grounds, are possessed of a luminosity and vigor that point to their inspiration in earlier works by Baselitz—the first nude self-portraits and portraits of his wife Elke, for instance, culminating in the monumental, authoritative Schlafzimmer (Bedroom, 1975), and the ferociously painted, wild-looking Orangenesser (Orange Eaters) from the early 1980s. In the new paintings, however, Baselitz’s touch is much lighter, the paint is thinner and more fluid, like watercolor, and the forms are broken. The result suggests a fleeting, fragmentary view, due in part to the fact that Baselitz brushes paint onto small pieces of cloth that he then impresses on the canvas laid out on the floor; and in part to his use of stencils or templates to block off areas of canvas or to achieve sharp contours. The procedure is analogous to collage, while the effect is of an image that pulsates with a dancelike energy—with the rhythms of life itself.

The grandest of the San Francisco paintings (over eight feet high by thirteen feet wide) is a double portrait of Baselitz and Elke in that tradition of portraits of couples of which Otto Dix’s unsparing portrait of his ageing parents, Die Eltern des Künstlers II (The Artists’ Parents II, 1924), in the Sprengel Museum Hannover, has served as a model for Baselitz in the past. But there is no hint here of the preoccupation with vulnerability and physical decline that characterizes his earlier portraits. This elderly naked couple exude resilience and even zest, their enduring love for each other clearly as strong as ever, whatever the future holds. The painting’s long, alliterative title gives a clue to a more recent artistic affinity: Wenn das Wörtchen wenn nicht wär, wär’s ein Lichtenstein gewesen translates as If if were not a word, it would have been Lichtenstein. The bright, Pop colors of the double portrait, and of many of the new paintings inspired by the Orangenesser, recall Roy Lichtenstein, an artist who often alluded to previous styles and subjects in art history just as Baselitz does. Both believe that a painting is essentially a two-dimensional object whose flatness must be respected, rather than a window onto the world, an illusion of reality. In 1995 Lichtenstein described his own Perfect and Imperfect abstract paintings as “meaningless,”2 perhaps echoing the remark of Willem de Kooning—another of Baselitz’s heroes—that “it is exactly in its uselessness that [painting] is free.”3 Baselitz would certainly have concurred with de Kooning’s belief that art should not be obliged to reflect social, political or religious dogma.

The Hong Kong paintings depict tall, vertical figures, usually in pairs, but one vast canvas shows three figures, resembling violet X-rays of the human body, side by side on a black ground. With the exception of this latter painting, all the figures are black, silhouetted against gold, like Byzantine icons or Egyptian funerary monuments. The gold describes the area between the figures’ legs and around the contours of their bodies and heads. In other words, Baselitz did not paint a figure on the unstretched canvas on the floor; he painted negative space, in gold paint, then pressed the canvas covered in black paint onto the canvas laid out on the floor. What appears on the upper canvas once it is peeled back are figures consisting of the black ground surrounded by gold—a reversal of the usual process of painting the figure as a positive form against a neutral, uniform background.

Baselitz’s working life over the last decade has been interrupted by periods in hospital. From about 2014 to 2018, an unflinching preoccupation with his own decaying body dominated his work. Elke’s naked body joined that of her husband in seated double portraits, their poses reminiscent of Dix’s portrait of his parents; while in other canvases each was also portrayed alone, standing unconfidently, or hesitantly descending a staircase—an ironic reference to the painting Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 (1912), by Marcel Duchamp, who famously went on to denounce “retinal” art. The figures tended to be flesh colored, mottled gray or deathly white, and were shown against oppressive black backgrounds. Baselitz also used an aerosol spray that created a nebulous effect, like an aura or emanation. The figures seemed to float like ghosts.

In the new paintings they have been reduced even further, to little more than sexless, faceless shadows, as flat as tombstones or corpses on a mortuary slab, which they bring to mind. The artist’s hand has not modeled them; there is no suggestion of volume, depth, or perspective. In some instances the gold paint appears to be eating into the black figure, as if he or she were disintegrating before our eyes. In postwar painting, both Francis Bacon and Andy Warhol produced compelling works in which shadows are equated with dematerialization and ultimately death. The Hong Kong paintings are arguably closer in spirit to Warhol’s multipart series Shadows (1978–79), sharing those works’ massive scale, their repetition of simplified forms to the point of abstraction, their interplay of positive and negative shapes, their removal of the artist’s direct touch—in Warhol’s case by screenprinting photographs onto canvas—and above all their feeling of transience. If Baselitz once contemplated achieving an impersonal, styleless style, in these poignant new paintings he has come nearer to it than ever before. They signal a renunciation of corporeality of almost Shakespearean proportions:

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on; and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.4

1The exhibition at Gagosian in San Francisco opened on March 12, 2020. The exhibition at Gagosian in Hong Kong is planned but not yet scheduled.

2Roy Lichtenstein, quoted in Yve-Alain Bois, Roy Lichtenstein: Perfect/Imperfect, exh. cat. (Beverly Hills: Gagosian Gallery, 2002), p. 18.

3Willem de Kooning, “What Abstract Art Means to Me,” talk delivered in “What Is Abstract Art?,” symposium at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, February 5, 1951, in The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art XVIII, no. 3 (Spring 1951), pp. 7–8.

4William Shakespeare, The Tempest, 1610–11, ed. Frank Kermode, Arden Shakespeare Paperbacks (London: Methuen & Co., 1970), act IV, scene 1, lines 148–58.

Artwork © Georg Baselitz; photos: Jochen Littkemann

![Georg Baselitz, Ohne Titel (nach Pontormo) (Untitled [after Pontormo]), 1961.](https://gagosian.com/media/images/quarterly/essay-baselitz-bildung/qxhewJId3rEi_275x275.jpg)