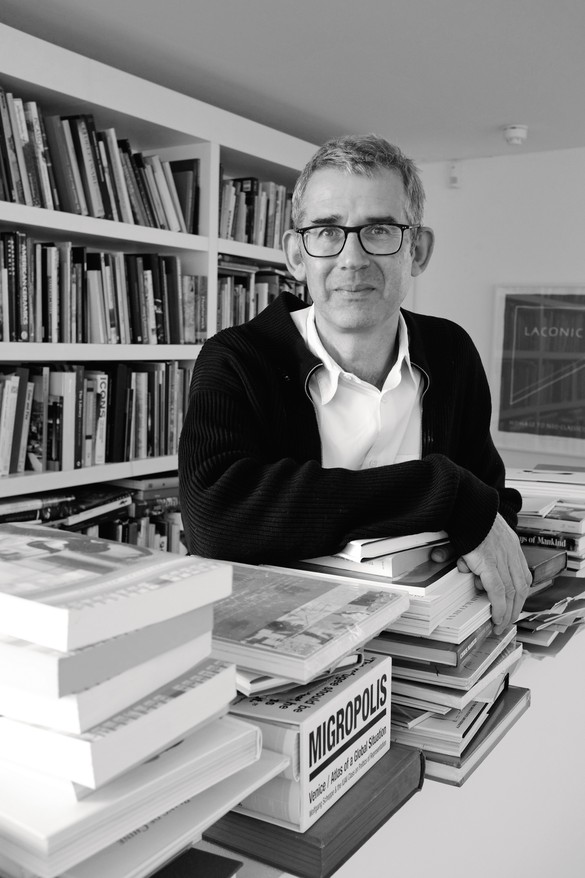

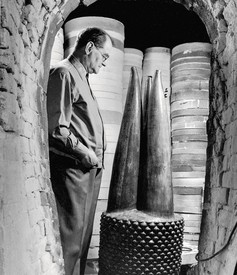

A potter since childhood and an acclaimed writer, Edmund de Waal is best known as an artist for his large-scale installations of porcelain vessels, which are informed by his passion for architecture, space, and sound.

Alison McDonald is the Chief Creative Officer at Gagosian and has overseen marketing and publications at the gallery since 2002. During her tenure she has worked closely with Larry Gagosian to shape every aspect of the gallery’s extensive publishing program and has personally overseen more than five hundred books dedicated to the gallery’s artists. In 2020, McDonald was included in the Observer’s Arts Power 50.

Alison McDonald Your exhibition in Venice comprises two presentations in two different venues. Can you describe this structure?

Edmund de Waal Yes, it’s one project in two parts. One part is completely grounded in the experience of the Venetian Ghetto. This takes place throughout the Museo Ebraico di Venezia, and a small part is presented alongside the Canton Scuola synagogue, an extraordinary sacred space. It will be a journey through the synagogue up into the sukkah. These are incredibly significant spaces.

This first part comprises a series of installations based around the Psalms. It includes wall-hung vitrines, a table piece, a text-based installment, and an element based visually around the tall buildings in the Ghetto Nuovo. Within the exhibition is a piece entitled tehillim, which is Hebrew for Psalms. In sum, this part of the project really takes the idea of the Psalms as songs and poems of exile, and then creates contemporary works to reflect that.

AMCD What does tehillim consist of?

EDW The space has a series of walls, each with elements of gold, porcelain, or marble. The light comes and goes, like a call and response, between these materials. The Psalms are structured in this same manner, the call and the response. To continue this dialogue I added a series of eleven vitrines containing white porcelain, marble, and gold.

AMCD Could you describe the sukkah and the visitor’s journey?

EDW The sukkah is one of the most famous spaces in the Ghetto. It’s been used for celebrations for three hundred years, and it’s the only space in the whole museum where you look down into the square of the Ghetto. You’ve wandered through all of these complicated, tiny, vertiginous little rooms—which is akin to the experience of the Ghetto, of course—and then suddenly you’re in this top room and you can look down into the square with kids playing football and people hanging their laundry and couples sitting together.

AMCD Traditionally in the Jewish faith, the sukkah is a temporary structure in the open air, built as part of the celebration of Sukkot. So the Canton Scuola synagogue must have moved the structure inside and made it a permanent part of their building?

EDW Yes, about a hundred and fifty years ago they roofed it over. The roof is extraordinary; it’s like a Louise Bourgeois installation with metal bars and straps going across the top where they hung the tent-like structures during the festival of Sukkot. I wanted to take that feeling of sacred space and pair it with a cityscape-like installation using a series of tall vitrines next to each other, almost one on top of the other. It’s a peaceful vision of what the Ghetto really is: a place of fantastic conversations, music, poetry, and cultural exchange.

AMCD So you’re describing a celebration of life and cultural exchange, but there’s also the element of oppression. Given your work in both art and literature, there’s surely recognition of that in this exhibition?

EDW The Ghetto is obviously a place where there’s an articulation of the people with power and the people with no power. You’re walled in, gates are shut, there’s a curfew, you’re guarded, you’re policed. All these realities are powerfully present. The Venetian Ghetto is the first ghetto in the world; this is where the word originated.

There’s an implicit understanding and knowledge of the ghetto as a place of being-apart. That’s a history that I know well and I’ve explored, particularly in my work at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, but for this exhibition I wanted to do something completely different, which was to look at the ghetto as a place of agency and a place for the generation of ideas, a place where multiple languages are spoken, where poetry is written, music is composed, books are printed, and conversations started. I’m looking at the focus on pain and restriction, but I want to turn it on its head, to have a lyrical rediscovery of these spaces as locations of energy, rather than only as places of melancholy.

If you look at the achievements made possible by Jewish culture in the Ghetto of Venice, like the printing industry, it’s astounding. The dissemination of ideas across the known world made possible by this place—it’s absolutely incredible. So you see, it’s easy to have one simple take on the Ghetto as a place of disparity, but that’s actually a bit one-sided and it doesn’t get to the full truth.

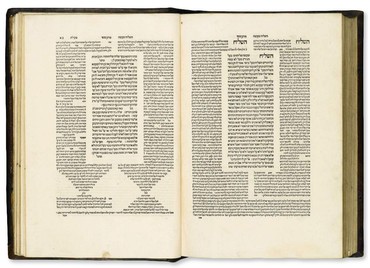

AMCD Speaking of printing, you’ve cited the sixteenth-century Venetian publisher Daniel Bomberg as an inspiration. Understandably, given that you’re presenting in his city, he plays a key role in psalm. How did his work inform the project?

EDW I’ve known Bomberg’s work for a while. I was amazed by his ideas about bringing text, context, subtext, and commentary together in one place in an incredibly sophisticated way. His publications are able to hold different voices together on one page. It’s incredibly powerful. And of course I’m interested in how text works visually; that’s part of my life as an artist and writer. So looking at Bomberg’s Talmud—all of those incredible pages—I began to see it as an installation. It was something I had to work with and through and toward. Hence the second part of the exhibition: library of exile.

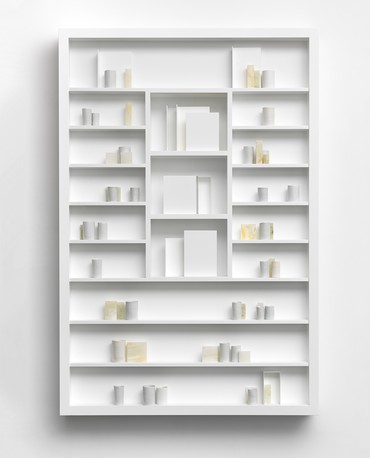

AMCD For this second part of psalm—in a different location, the Ateneo Veneto—will the whole installation take place in one room? Or will it include multiple rooms, like the first part?

EDW The library will be constructed in one room. It’s like a pavilion, a freestanding structure that stands as a library and as a sculpture. As you mentioned, it’ll be housed in the Ateneo Veneto, which is an amazing centuries-old space that has the most extraordinary ceilings. It will hold two thousand books of poetry, each authored by a writer who had been forced into exile. So this space is a new library that reflects a culture of people moving, of migration, of conversations in different languages, of travel, of diaspora. The books themselves are in thirty-two languages from all around the world. I’ve been conscious to include a variety, from Ovid, writing two thousand years ago, all the way through to books published this year by people who have just left Syria.

AMCD You’re including translations, and I understand the importance of that, but will the library also include versions in the original languages?

EDW Yes.

AMCD What was the process of selecting the books like?

There’s something very powerful about the literature of exile, the experience of being away from the place in which you were born. That’s what the Psalms are and that’s what this library will be.

Edmund de Waal

EDW The process is still unfolding. One of the great joys of this project is that over the last year I’ve spoken with so many people, each with unique suggestions. In my studio in London we see parcels arriving day by day from all around the world. It’s incredibly moving. What’s happening is that people will say, “Have you read Joseph Brodsky?” Brodsky was a Russian poet, born in Leningrad, who emigrated, because he was Jewish, to America. So of course, I must have Brodsky. So I have his text in Russian, but I also have his text in English. But then someone says to me, “Brodsky, amazing. Did you know that he was passionate about Venice and there are amazing Italian translations of Brodsky?” So now we have three books by Brodsky. And then someone else says, “Okay, you’ve got Brodsky in Italian, did you know that he also translated this other author, who was also exiled from his country and who then went to Paris in . . . ”—and so on. And the result is this wonderful chain of powerful connections between writers, translators, and publishers. That’s how libraries work. My dream for this project is that wherever you come from in the world you’ll be able to sit down and find books in your language, some of which you already know and others that will be new to you.

There’s something very powerful about the literature of exile, the experience of being away from the place in which you were born. That’s what the Psalms are and that’s what this library will be. Just as the Ghetto generates an incredible power of cross-cultural conversations, what I’m trying to do with this library is make a really beautiful, intriguing space where different kinds of literature and experiences can talk to each other across time.

AMCD How does your sculpture enter the library?

EDW There are four installations embedded in the walls of the library as well, each a reflection on Bomberg. And the outside walls of the library are covered in a liquid porcelain slip and gilded with gold. Written on those walls is a new text that I’ve composed to document the history of all the lost libraries of the world, from Nineveh thirty-five hundred years ago all the way through today.

AMCD Let’s talk for a moment about why libraries get lost. Libraries represent knowledge, and people in positions of power who are seeking to eradicate opposition will often purge libraries as a way of eradicating a base of cultural understanding. If I’m not mistaken, your family lost a library as well.

EDW Yes, people in power often try to control literature and books. There have been book burnings and deliberate destructions of libraries throughout much of human history. My grandfather, when the Nazis invaded Vienna in 1938, had his famous library looted. Or think of isis destroying libraries in Timbuktu and Mosul. And in this really difficult, polarizing moment in history, I wanted to make a new library. On the outside of my structure there’s this intricate history of loss, but my hope is that when you walk inside this installation you find the regenerative excitement of books happening across time.

Importantly, on this note, there’s a whole program of events happening in and around the library as part of psalm. There are events for children’s storytelling, conversations between translators, and talks by poets and novelists.

Another detail that excites me is that inside every book there’ll be a bookplate. Anyone who reads a book, or has a response to it, will be able to write in it, resulting in new conversations.

AMCD Will the library evolve over the course of the exhibition?

EDW The structure and installations will stay the same, but as you well know, Alison, nothing ever remains exactly the same. I have every expectation that some books will be borrowed, stolen, or disappear, and I have absolutely no doubt at all that during its life in Venice, people will bring books and give books to the library and have brilliant ideas about the things I’ve missed. It will evolve, and I’m hoping it will become a traveling library in the future as well.

Edmund de Waal: psalm, Museo Ebraico and Ateneo Veneto, Venice, May 8–September 29, 2019; library of exile subsequently traveled to Japanisches Palais, Dresden, Germany, November 30, 2019–February 16, 2020, and British Museum, London, August 27, 2020–January 12, 2021

Artwork © Edmund de Waal