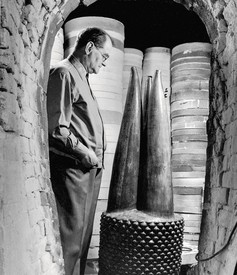

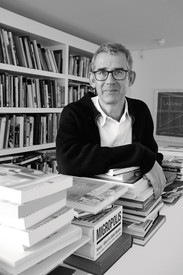

A potter since childhood and an acclaimed writer, Edmund de Waal is best known as an artist for his large-scale installations of porcelain vessels, which are informed by his passion for architecture, space, and sound.

Jan Dalley I wanted to start by asking you about the two strands of your artistic life: the making and creating in the plastic world and the writing. Sometimes they seem to come together very closely, as, for example, in your marvelous book about your search for porcelain [The White Road: Journey into an Obsession, 2015], which obviously played very closely into your artistic practice. Is there sometimes a pull apart in those two strands?

Edmund de Waal There is a basic pull in the sense that when I arrive at my studio door in West Norwood and I let the dog off the leash, I can either go upstairs, where there are towers and towers of books, or to the other end of the studio, where there’s clay. Sometimes there’s an absolute imperative to finish a text, to let a text go into the world, and sometimes there’s nothing I can do but go and sit at my wheel and pick up some porcelain and make another vessel.

That’s a forced dichotomy, of course, because actually in the making I’m always thinking about words as well, and when I’m writing, there’s so much making going on, so much making of form in the way that I’m trying to bring language together, that I have no idea what I’m doing anymore. No idea. Except that sometimes it turns out to be a book, sometimes it turns out to be an exhibition, and quite often now, it turns out to be an exhibition where I’m writing on the walls of the gallery. There seems to be a kind of spilling over from one thing into another.

in the making I’m always thinking about words as well, and when I’m writing, there’s so much making going on, so much making of form in the way that I’m trying to bring language together.

Edmund de Waal

JD As you describe your writing process, it is very much like an accumulation, as you might accumulate clay into a vessel. It sounds as if words, for you, are somehow solid chunks of something—

EdW They are. A word has presence in the world. A word has shape, it has an aural quality, it has a definition in the world as a sound—as a breath, as an articulated thing—but also, of course, it has incredible beauty. I’m sure as I’m saying this these are words which I’m putting down in front of me, which is why I’m closing my eyes, but a word on a page is an incredibly deep, beautiful object. And so, one word on a page and then another, and you have sculpture. When I think about the texts that matter to me—it could be Mallarmé breaking apart words and scattering them powerfully across a page, or it could be Paul Celan breaking open words and putting them back together, or Emily Dickinson—often the poets I come back to again and again have that sense of the “thinginess” of a word, that marvelous Latin word haecceity, or “thusness,” of a word. So, when I’m making text, there is a sense for me that it is a kind of sculpture. I touch the words when I’ve written them.

JD In one of your most recent projects, your creation for the Venice Biennale, you have indeed literally married books with ceramics and porcelain, and you have literally written on the walls.

EdW Yes.

JD Could you describe the project for people who don’t know it?

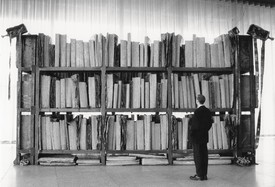

EdW It is by far the most personal and significant thing I’ve ever managed to work on. It’s an exhibition in two parts, called psalm. In both Jewish literature and life and in Christian life, the Psalms are the great songs of exile. Part of the exhibition is in the Venetian ghetto, where it threads its way up into one of the synagogues and into these extraordinary sacred spaces there. It’s a whole series of reflections on the Psalms. The second part is a library of exile, in a beautiful baroque space. It’s a freestanding library, like a pavilion, on which I’ve washed liquid porcelain and then inscribed a history of all the lost libraries of the world, from Alexandria through the burning of rabbinical libraries and Muslim madrassa libraries, all the way through the twentieth century—through the destruction of my grandfather’s library in Vienna, through Sarajevo—and ending in Mosul. Inside are two thousand books written by exiles, from Ovid on, in forty languages—two thousand years of people writing about carrying their language with them, talking about what it means to be homeless and to find a home in language.

When you open up a book up in the library, it has an ex libris inside, and you are asked to write your name and suggest other books, so the library is growing. It’s a proper working library that brings you into this truth that language is migratory, and that we depend on people crossing borders, and that we need to valorize this whole experience of moving in language from place to place.

We’ve had extraordinary people coming and talking in the space, and we’ve been working with refugee groups there. The whole library moves to Dresden in the autumn, to be in the Japanisches Palais, where there used to be a library, which was destroyed in 1945, and then it comes to London, to the British Museum.

JD So in a sense, it’s an immigrant library as well, isn’t it?

EdW Yes, yes.

JD It’s a migrating library. An immigrant to every culture that it comes into but also a settler in every culture. I believe all of the books are in translation, aren’t they?

EdW No, not all of them. The great, beautiful thing about a library is that it doesn’t belong to you [laughs]. As soon as the door opens, it’s not yours anymore. And so I thought everything should be translated—but actually, no, people wanted books in their original languages. So we changed it. And the point about that, the point about why libraries matter, is of course that you are completely alone in the library—you are irreducibly there, by yourself—but you are surrounded by voices. It’s a plural existence.

So what’s happened is that the library began in Venice, which has such a powerful identity, and then it had to go to Dresden, to where porcelain began, and then it absolutely had to come to London, and then what is incredibly moving for me is that the whole library is then going to be part of the new library which is being built in Mosul. The library that was destroyed by ISIS is being rebuilt, and so the whole library will become part of a foundation of a new library in Mosul.

JD Permanently?

EdW Permanently.

JD I want to ask you about new projects. Despite your description of the way that your books and your writing arises, from various forms of inspiration, similar perhaps to the inspiration for your visual art, you have also written books that have taken considerable research. Not only, of course, the wonderful Hare with Amber Eyes, but also The White Road, which traces the history of porcelain and the concept of whiteness and everything else, which took you to three continents and goodness knows where else.

EdW Yes. Researching for The White Road did take me to China, to Jingdezhen, and all the way down the Silk Road into extraordinarily complicated bits of history, including really tough bits of twentieth-century history. You have to be in a place, you have to walk it, you have to talk to people, you have to sit on the street with a cup of tea in the Chinese village, or in an archive in Dresden looking up destroyed manuscripts from Dachau—you have to be there in order to walk alongside the people who were there before. That’s what happened with the Hare, and that took seven years. I’m speeding up, if it was five years for The White Road [laughter].

But it’s okay for things to take a very long time. It doesn’t mean it’s better, but for me it is absolutely necessary.

JD Your work in particular is the kind of thing that has been learned and perfected over very many years. When you were starting out, you started in Japan, correct? I believe that people study for years before they even touch a wheel.

EdW Yes.

JD And so presumably you always had the sense of this being an art form in which time was extremely important.

EdW Yes, absolutely. That’s the great joy of deciding early that this is your life—or having your life decided for you by feeling a sort of a vocation. You actually do know that it is going to take decades. There is a deep parallel with music. You know how long it’s going to take to be able to build up a thematic language, a bodily language, of how you might express yourself; you might not be able to inhabit the Goldberg Variations until old age. With clay, I’ve now had fifty years of making pots, and I’m sort of beginning to work out what a vessel is. I’m beginning to work out the relationship of a volume and an outside space, and how one object in the world displaces a particular kind of energy around it, and why you might want to bring in another object. It’s beginning to work for me.

JD That must be something, the sense of working out what an object is. The space it takes up in the world must be something that you’re working out in an additionally interesting way now that you’re doing quite a lot of exhibitions where your work is in concert with something else—for example, your exhibition at the Frick, where your work has been placed in conjunction with and in contrast to works of previous centuries.

EdW Yes, the phone call from the Frick was quite special. It’s a complicated thing, because you’ve got a sense of how you want to bring an energy field together with the work you’re making, and you’ve got Titian and Bellini and Cranach all in the same visual field. You are talking with these extraordinary works of art that have such a gravitational pull towards them, so what are you going to do in those spaces? Hubris has been left at the door. My way of doing this is to try and understand how you move through space, so it’s a whole beguiling conversation about the place of sculpture. And speed, how you move through a building.

JD And making it new for the viewer.

EdW Yes.

JD So, when the viewer who might be familiar with or a bit inured to a gilded piece of furniture—when they see something of yours which is, let’s say, also using gold in an interesting way, it makes it new for the viewer.

EdW Yes. People rush through the Frick to see Ingres’s great portrait of the Comtesse d’Haussonville—that great portrait of her looking like she owns the world. Below her, Frick put an incredible gilded eighteenth-century table by [Pierre] Gouthière. It is the most extraordinary piece of sculpture—it’s a whole series of extraordinary moments of gold work, with a Turquin marble top to it. I put a vitrine on the table, and the vitrine sits reflecting gold down into it. So you are aware of where things sit in the world.

The idea of being in a particular place and using collections to illuminate and initiate all kinds of other synapses, other kinds of movement, is something I really care about.

JD Can I ask you about your use of those particular materials: gold, which we’ve mentioned, and also marble, which has become important in your more recent work? In your Venice exhibition, in the women’s gallery of the synagogue within the ghetto, are these wonderful pieces which use gold and marble. These were substances which were forbidden to the Jews; they weren’t allowed to use them.

EdW Yes, it was the ghetto. There was a curfew and a wall, you know—the windows were blocked up, boats patrolled the canal around it . . . The list of proscriptions is absolutely incredible to read. For one, you weren’t allowed to use marble to build your synagogue. So I brought in marble. And gold. I made the thinnest piece of porcelain that you’ve ever seen, beyond paper thin, and then gilded it. So it sits like a leaf, really—it could blow away. And then I put the gold and the marble together so that there is an aura, an extraordinary halo, and then the windows are open and the light changes during the day, and this whole piece, tehillim, which means “psalms,” changes hour by hour by hour. It’s a way of talking to deep history—deep, complicated history—and also trying to make something which is really beautiful.

JD Because of course that’s what the historical creators you’re celebrating were doing—when they couldn’t use marble, they would paint trompe l’oeil marble, and it was just incredible, so beautifully painted.

Can I ask you what’s next? I know that you are very busy with exhibitions, but have you got another book on the go?

EdW Yes, there is something happening. I can’t tell you the subject, but it’s beginning to take shape. I think it’s another five-year book. And then exhibitions, you know. I’m doing a really lovely thing with the Henry Moore Foundation next year, at Perry Green. I’m choosing pieces of sculpture by Moore which you can touch. It will be an extraordinary moment, you’ll actually be allowed to touch the Moore sculpture. And then putting together a whole extraordinary exhibition of Moore’s drawings of his own hand. So, there will be something on touch next year.

JD Ah, is that going to be the subject of the book?

EdW Honestly, you’re very good, Jan. But no, I can’t tell you [laughs].

JD [Laughs] Oh well, I had to try. Well, that’s absolutely lovely. Thank you so much for sharing.

This is an edited version of the conversation between Edmund de Waal and Jan Dalley at the FT Weekend Festival 2019, Kenwood House, London, September 7, 2019; Edmund de Waal: psalm, Museo Ebraico and Ateneo Veneto, Venice, May 8–September 29, 2019; Elective Affinities: Edmund de Waal at the Frick Collection, Frick Collection, New York, May 30–November 17, 2019; library of exile: Edmund de Waal, Zuzanna Janin, Mark Justiniani, and the Damascus Room, Japanisches Palais, Dresden, Germany, November 30, 2019–February 16, 2020; This Living Hand: Edmund de Waal presents Henry Moore, Henry Moore Studios and Gardens, Perry Green, UK, April 3–October 25, 2020

Artwork © Edmund de Waal