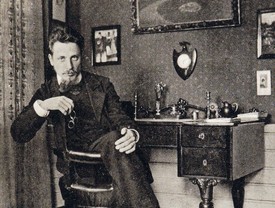

Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

A potter since childhood and an acclaimed writer, Edmund de Waal is best known as an artist for his large-scale installations of porcelain vessels, which are informed by his passion for architecture, space, and sound.

Richard CalvocoressiThe painting we’re sitting in front of as we speak is by [Georg] Baselitz, which I think is interesting, because the notion of the artist’s touch, the artist’s signature or handwriting, if you like, is something that Baselitz has always tried to get away from. Even though the subject is a hand, the image actually hasn’t been touched by the artist’s hand at all; it’s the result of a transfer technique that Baselitz has developed over the last few years, by painting the subject on a blank canvas on the floor and then laying on top of it a canvas with a black ground, applying pressure to the back of the canvas, and then peeling it away. And this is the result. So it’s a kind of styleless image, if you like.

Edmund de WaalWell, it’s a wonderfully perverse place to start, isn’t it, Richard, because apart from it being the hand of God descending over us in a kind of blessing, what have we got here? We’ve got a whole series of complicated things about facility, about someone who wants to escape touch, someone who has an ability to reinvent the scale of the hand, which I think is really interesting when we’re thinking about touch. The hand is only this big, but actually how big is the world through touch, how can we re-create that? But also, the sense of the agony of how you represent a hand as an image as well. All of this congregates in Baselitz’s work.

One of the many things I find extraordinary about Baselitz are these moments of rupture in his life, when he seems to say, “I can do this with my hands now, but there’s a danger in having that facility. I don’t want to continue along that path of being able to do these things, have that signature, have that particular handwriting, that discernible connection between my hand, my art, and me.” And he ruptures it. There’s a gap, a lacuna, and he reinvents it and starts again with his hand.

RCYes, it’s this resistance to all kinds of formulae, to becoming too complacent about what he does, so he will deliberately do difficult things like painting with his fingers, or inverting the image. He’ll make sculptures out of massive tree trunks with chainsaws—completely ignoring thousands of years of artists who’ve made sculpture and developed particular tools for the job.

EDWI don’t know about you, but when I look at the finger paintings, my hands itch; they absolutely come alive, because I can see the iterative mark making there. I want to put my hands on his painting and do those pictures. You can read his touch. And when you see the chainsaw sculptures, you can feel those transitive movements that he makes. In all these cases, he’s bringing you back to a somatic kind of experience of beginning art again.

Edmund de Waal (left) with Richard Calvocoressi at the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, in front of Georg Baselitz’s La mano – durchgehen (2019). Artwork © Georg Baselitz 2021

RCThat kind of ur-painting, ur-sculpture, and unlearning centuries of academic teaching.

EDWUnlearning because he has to, because of who he is in history. He has to work out what it is to be an artist in postwar Germany.

RCYou’re absolutely right. Having grown up under two totalitarian regimes, National Socialism and then Communism, he’s absolutely allergic to the idea that art says anything, because of the way art was hijacked by those regimes to exhort people, to proclaim—particularly figurative art. Which is why I think when he comes to West Berlin in 1957, 1958 and finds that all his contemporaries are painting in a kind of Abstract Expressionist way, he feels very confused, because he’s been conditioned to think that art must have a message, it must serve the state, and now he enters this sea of libertarianism, freedom, democracy, where you can do what you like. So what he does is try to combine elements of both, of socialist realism and Abstract Expressionism, but at the same time wanting to get away from that very important component in Abstract Expressionism of the artist’s self, the ego, the gesture.

EDWThis episodic unlearning makes me think about Black Mountain College in the 1950s, that extraordinary moment where you have Anni Albers, the greatest textile artist of the twentieth century; you have Josef Albers; you have Charles Olson talking about the breath and the hand in poetry; you have Cy Twombly; you have John Cage talking about how you make music by using your hands, the percussive nature of the hand happening in the world; you have Robert Rauschenberg. All these intersections of people unlearning from each other: Cage talking to Olson and thinking, actually, I’ve got to take my language apart, or Merce Cunningham talking to Anni Albers about bodies coming together like fiber. All these things come back to the body, to how you think about touch, how you think about one person next to another, how you make marks. And out of that extraordinary moment, you get Twombly’s practice, Cunningham’s first extraordinary things, Rauschenberg’s first Combines. It’s unlearning through touch. So it’s not that beautiful long craft tradition, which I so admire and have been immersed in. It’s a very extraordinary moment of turning the world upside down and inside out.

RCDo you not think it starts, though, in the Bauhaus and the preliminary course directed by Johannes Itten, which was very much based on ideas of child education that were current in Vienna and on the child’s experience of the world, which is learned largely through the senses? Before you could go on in the Bauhaus, to the metalwork department or whatever it was, you had to abandon your preconceptions at the door.

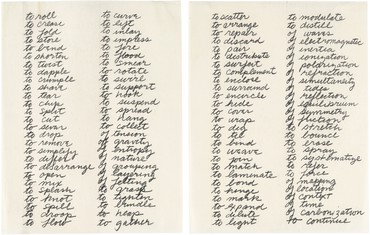

EDWYes, and play takes you back to an openness to the material world. It’s not saying “wood,” “clay,” “metal,” “fiber.” It’s saying “pinch,” “squeeze,” “rip”—all those things that you see children do when they haven’t yet been told about how to demarcate the world into particular transitive actions. The great, iconic list of touch, of course—which I have returned to and written about and talked about over the years—is Richard Serra’s Verblist from the 1960s, now at the Museum of Modern Art, where in order to unmake himself and relearn how to make sculpture, he creates a long list of verbs about how to touch the world.

RCIn the exhibition you’ve curated at the Henry Moore Studios & Gardens [This Living Hand: Edmund de Waal Presents Henry Moore], there are three sculptures by Moore on view, two bronzes and one stalactite piece, and what’s so exhilarating is that visitors are encouraged to touch the sculpture. Of course, that’s exactly what Moore wanted. He loved it when people could get a sense of their form by feeling them.

EDWThere are extraordinary photographs from the 1950s showing those great sculptures by Moore at housing estates, and children climbing on them and people sort of leaning against them. The sculpture that I wanted in the show and we couldn’t get because of the pandemic was the Madonna and Child [1943] from Northampton. It’s an extraordinary sculpture, made from Hornton stone, and the reason I wanted it is because the feet of the Madonna are worn away by touch; over the decades people have come up and rubbed the Madonna’s toes almost away. Isn’t it interesting what repetitive touch records in terms of how we relate to the world?

There were three things I wanted to do with This Living Hand: One was to have a great sort of Wunderkammer of favorite things from Henry Moore’s house, which he used to pass around, as you know well. You could come in and—

RCPlay with things, yes.

EDWThat wonderful kind of democracy of touch; everything should be touched, and it’s the beginning of form for him. Then that extraordinary autobiography he created, obsessively drawing his own hands, you know, from 1922 right until the end of his life, which I think is very beautiful. And then also other people’s. I think the drawings he does of Dorothy Hodgkin’s are in many ways the most extraordinary drawings of hands of the twentieth century.

RCHands as an indication of character, rather than the face, is something that also comes through in this exhibition [The Human Touch]. The face isn’t always the best vehicle for somebody’s character.

When you see objects that have been known and handled, you do begin to understand what incremental touch does in the world. It’s about kindness. It’s something profound about touch and memory.

Edmund de Waal

EDWNo—well, I would always argue that [laughs]. Of course the greatest painting in the Fitzwilliam is a picture of hands—Extreme Unction [1638–40], by [Nicolas] Poussin. It’s an articulation of all kinds of movements of the hand, and then there is that core powerful image of one hand meeting a dying person. It’s the most powerful example of what touch can actually mean. It’s sacramental touch, and that happens at points within this exhibition. You also have, of course, iconoclastic touch, and you have the fist as well—

RCVandalism—

EDWAnd vandalism, yes.

RCDefacing.

EDWDefacing, erasure. And creative erasure.

RCOf course.

EDWThe palimpsest. I’ve always thought that Twombly, who was thinking about touch, was the person who understood what a palimpsest is in the most creative way, that idea that you find something, you touch something, you write something, and then you erase it. It’s a different haptic experience, erasing something, but what you’re doing is layering on—

RCYou’re leaving a trace.

EDWYou’re leaving another trace. Then that allows you a space to write or paint or whatever you want to do in a space that has already been touched.

RCIt applies to Frank Auerbach, who applies paint and scrapes it off, applies paint, scrapes it off, until finally he’s happy with the image. It applies to Gerhard Richter to a great degree. And of course the most famous example of this is Rauschenberg rubbing out the [Willem] de Kooning drawing.

EDWYes. It takes us back to that list of possible movements. Because the range of opportunities to touch the world, to touch paper or canvas, are so manifold that actually you really have to read objects with enormous sensitivity to understand the complexity of the movements that have been involved.

In this museum, there are Korean tea bowls that I’ve known for a good forty years or so. And when you look at a tea bowl, you might think, oh, ceramics, it’s been thrown on a wheel, how complicated can that be? Of course, what a tea bowl is, actually, is the iconography of two hands. When you see a tea bowl, it’s a very un-Western sense of what touch might be. It is to be picked up only in one way, with two hands, and used. And in the making of it, all these extraordinarily complex haptic gestures are involved, of making the clay come down to the wheel, of pulling the clay up, that iterative, repetitive bringing of the clay up into the walls, the cutting of the pot from the wheel, the trimming of the base of the pot, which is a beautiful series of circular movements into the clay, and then the dipping into glaze. All of that happens in those Korean tea bowls, and when you see them, you’re seeing a process of someone making something. You’re seeing an unfolding of touch within an object. And when you see one, you absolutely want to reach into that vitrine and pick it up and be brought back into that unfolding series of moments of touch.

That is absolutely crucial, to be able to read objects in that way, to bring us back to how we understand the world through touch, not just the hand as an image, but the hand as an occupier of space and a creator of space around an object.

RCIn your show at the Moore Foundation, you’ve positioned four benches made of Hornton stone in the main gallery [tacet X, tacet XI, tacet XII, and tacet XIII], and outside, you have a basin of Hornton stone [stone for two hands and water]—Hornton stone being one of Moore’s preferred materials for carving. Is this something you’re going to develop in the future? You haven’t worked in stone before.

EDWThe reason for the benches was that I hate walking around exhibitions not being able to sit down. I just want to stop, you know? I worked with Corin Johnson, who’s a wonderful stone carver, and chose these extraordinary seams of stone with beautiful fossils in them. They sort of have a worn top—it’s very smooth and slightly undulating so you actually want to feel it. Then there are some hidden spaces in the benches where you touch different indentations. And of course this is taken from the idea of a netsuke, from the idea that actually, an object is better if it’s been handled and worn away. When you see objects that have been known and handled, you do begin to understand what incremental touch does in the world. It’s about kindness. It’s something profound about touch and memory.

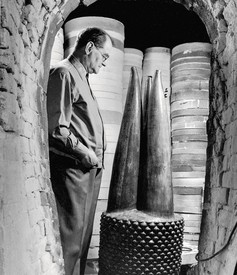

RCUp until the 1950s, really, Henry Moore was a carver. Modeling and casting doesn’t start until he’s in his late fifties, early sixties. The doctrine of truth to materials, which absolutely prevailed up to that point—you must let the piece of stone or the wood speak for itself, respect its inherent qualities—that goes out the window completely in the 1950s. He suddenly realizes that with clay or plaster, he can make objects much more quickly, and also on a much bigger scale.

So that’s when you start to get these things that are scaled up. That’s when he starts becoming interested in sculptors like Rodin. There are three bronzes by Moore in the gallery we’re sitting in now, two of which explore the relationship between the mother and the child, which is so important in terms of the child’s growing understanding of the world.

EDWThere is also an inversion here of the child and mother, which I think is very interesting. It takes us back to the complexity of touch because of the great foundational moment that Moore talked about throughout his life—

RCHis mother’s back, yes.

EDWExactly. He was the seventh child in a poor family, and he talked about going back home and rubbing his mother’s rheumatic back and feeling the bones beneath the skin—but it’s so profoundly unsentimental. So when you see mother and child and you see that tenderness and protection that’s going on, you also, of course, go back into that real response to a body.

Edmund de Waal, stone for two hands and water, 2021 (detail)

RCYes, and I think that’s why often the hands are enlarged, as they are in a lot of Surrealist art—you think of Salvador Dalí, for example. But the heads are often quite small, because in a way they’re less important. I think what he took from Rodin was that extraordinary rippling, moving, pulsating sense of the human body’s life.

Another interesting section of this exhibition [The Human Touch] is that on religion and different faiths: Christianity, Buddhism . . . We see the symbolic importance of touch in Christianity. There’s a wonderful medieval carving relief of the Visitation, there are images of Christ in the garden, Noli me tangere, et cetera, and of the disciple Thomas having to touch Christ in order to dispel doubt. Extreme Unction fits into this category of touch being such an important part of faith.

EDWI grew up in a pilgrimage site, Canterbury, and so I’m very conscious of what those repeated moments of touch mean. Because as in any pilgrimage site, there are places where repeated touch, repeated return to a particular site, has worn things away. People need to come and touch.

In the utter bleakness of bits of this last year in lockdown, I had a hand of Buddha on my desk in the studio, a bronze hand of Buddha from the eleventh century. I find this hand, which is a sacred object, so powerful. I was trying to write a book, I was making pots, I was trying to keep going . . . And I kept coming back to this, the openness of Buddha’s hand. It’s very interesting, isn’t it, across faiths, traditions, what an open hand means. Because when you see an open hand, you understand that it is an invitation. It’s not a grasping of something at all, it’s a release into the world.

RCConcealing nothing.

EDWConcealing nothing.

RCThere are images of the clenched fist in the exhibition, which is a form of political protest. There are images of sexual contact, either wanted or unwanted, consensual or what today would be categorized as harassment or assault. I found that fascinating. Very relevant to our times. This exhibition explores touch in so many different forms.

EDWDuring this last year touch has in so many ways atrophied and there’s so much anxiety around the hand. That’s why I made this place to wash your hands [for This Living Hand], so you can go into the exhibition and touch—but it was also symbolic and a way of celebrating positively. At the same time that all that’s been going on, that sort of distancing from hands, people have been making things and cooking as well, and desperate just to be in touch in so many creative ways. The digital world is full of people making stuff. And it’s wonderful.

This is an edited version of the online conversation “The Thinking Hand,” commissioned and hosted by the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, on June 30, 2021

This Living Hand: Edmund de Waal Presents Henry Moore, Henry Moore Studios & Gardens, Perry Green, England, May 19–October 31, 2021; The Human Touch, The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, May 18, 2020–August 1, 2021

Artwork by Edmund de Waal © Edmund de Waal

Artwork by Henry Moore © The Henry Moore Foundation. All images that include artworks by Henry Moore reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation