Albert Oehlen: Terrifying Sunset

The artist speaks with Mark Godfrey about his new paintings, touching on the works’ relationship to John Graham, the Rothko Chapel, and Leigh Bowery.

February 23, 2021

Hans Ulrich Obrist interviews the artist on the occasion of his recent exhibition at the Serpentine Galleries, London.

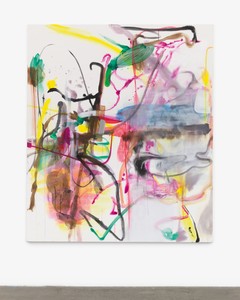

Installation view, Albert Oehlen, Serpentine Galleries, London, October 2, 2019–February 2, 2020. Photo: readsreads.info

Installation view, Albert Oehlen, Serpentine Galleries, London, October 2, 2019–February 2, 2020. Photo: readsreads.info

HANS ULRICH OBRISTLet’s start by talking about Spain. You have your place here in the Basque Country. How did this come about?

ALBERT OEHLENI went to Andalusia at the end of 1987 with Martin Kippenberger and moved into a house there, where I worked for a year. Then I stayed in Madrid for a few years. Since then, I’ve always had one foot in Spain—I always had a place here and another somewhere else.

HUOYou once told me that your transition to abstraction happened in Spain, in that year. Is that right?

AOYes, in Seville. It was just like that. I had the intention of becoming an abstract painter, but no idea how to do it. In Carmona, I made various attempts to go in that direction, and at some point it happened.

HUOWhat was the first abstract painting you made?

AOWell, I started by naming the work with the big mouth, the lips with the teeth inside and the uvula, Abstract Painting Number One (1988), with the idea that you can call something abstract if you no longer believe in the function of presentation or visualization. Another was a mash-up of an American flag. I didn’t mean to refer to the flag itself, but to Pop paintings. I tried out various approaches towards abstraction, like painting something figurative or recognizable, but not believing in it; that was one method.

HUOPainting something, but not believing in it. To turn to your show at the Serpentine: you made a Rothko Chapel in Beirut for Trance (October 22, 2018–September 2019) at Aïshti Foundation, and for the Hamburg exhibition Hyper! A Journey into Art and Music (March 1–August 11, 2019) at Halle für Aktuelle Kunst, Deichtorhallen. Your interpretation of the Rothko Chapel for your upcoming Serpentine exhibition is the opposite to the chapel in Houston but follows a similar idea.

AOYes, I’m approaching it from another side. It’s simply about the silence in the original Rothko Chapel in Houston. Back then, when I was there, you had this feeling of twilight and these paintings in which the eye could barely find anything to hold onto. If any spiritual effect were to be achieved, my question would be how much auto-suggestion would be necessary? Because you often hear trivial music in the context of reflection. I wondered if one couldn’t also reach a meditative state while listening to violent music.

HUOBy violent music, do you mean noise?

AOIt could be noise. I conducted some experiments on myself where I tried to create a lulling effect with different kinds of music. I thought about what it takes to achieve meditative states—with which music it’s possible and which not. With speed metal, and also with Electric Miles Davis, I experienced meditative states a lot. These results are of course only valid for myself. I came up with the idea of making a sort of violent chapel, without giving up on the desire for it to be about meditation. But I am not only referring to sound. The paintings should not fit into the cliché of having any calming features.

HUOYou have this idea for very specific music where fragments will almost stochastically appear in phases and then disappear. Some visitors might experience the soundtrack and others not. Can you say something about this?

AOI’m working with the Swiss band Steamboat Switzerland, a trio: bass guitar, drums, and Hammond organ. I know them via Michael Wertmüller, who for me is a genius contemporary musician, perfectly at home in the area between contemporary music composition, speed metal, and free improvisation. Time has passed since these things were invented, but for a while there seemed to be an antagonism between them. Today, you can connect or switch between these musical forms. It’s not a gag anymore. Steamboat Switzerland works in that area. I like them.

HUOThey’ll contribute sound elements to the exhibition, which aren’t always audible.

AOYes, in varying lengths.

Albert Oehlen's studio, Ispaster, Spain, 2020. Photo: © Esther Freund

HUOHow did the Rothko Chapel works start?

AOIn that first project in Beirut, there are cut-out and glued paintings made from advertising materials. Everything is held together in the trashiest way possible. They have two levels. One is the advertising material with the slogans on it—like “Everything Must Go!” or washing-machine commercials. That’s the level on which you can read the pictures and slogans. The other level is how it’s cut. Basically, you have these outlines taken from rioty [Salvador] Dalí paintings. You can recognize these figures when you focus on the cut outlines. You can basically see these two levels: the outlined Dalí pictures, and the motifs from the advertising material. It’s cut out and collaged. There’s a double layer of information, which is very colorful, and also very alarming through the Dalí motif.

HUOWhat is the reference to Dalí?

AOWhen you start getting into painting and you’re eleven or fourteen or so years old, you have to like Dalí. That’s obvious. In my generation, hippies and druggy people would have Dalí posters on their walls—he was their hero. There was a phase when this became too much and all humankind took a step back from Dalí because he was discredited as a showman. Many people who think they have good taste continue to reject Dalí because they think that the showman, money, and success stand in opposition to quality. How do you get out of that? You can overcome this by thinking about it, the easiest way being to read his autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1942). I believe that if you’re not convinced by then, you’ve missed the point. Have you read it?

HUOYes, I love that book.

AOIt’s really big. I think if you can revise your own judgment, it’s the most beautiful thing that can happen to you.

HUOHow does the chapel for your solo show in Beirut—the exhibition and music—relate to the mini chapel for the group show in Hamburg?

AOThey are done the same way. In the one in Beirut, the panels have the same size as the original Rothko Chapel. Before I made these, I made some 250 × 250 centimeter test-pictures firstly as a technical test to see how the frames should be made, how stuff could be glued, and how it appeared. There were six of them and now I presented these paintings in a box-like space.

HUOThere’s a soundtrack to these six paintings. You sit inside this box on a chair and listen to a Holger Hiller soundtrack.

AOYes, that’s correct. I’ve been involved with Holger for a long time now. Around the time when I was studying art, we were neighbors. I believe he was at the arts college as well, in a similar environment. I’m not sure if he was also a disciple of Sigmar Polke, but I have a lot in common with Holger and some time ago we did something together.1 He produced ten musical pieces, and I made ten graphics as an edition. The original project was on vinyl, but he burned them onto a CD, which we use for this project. He made a very precise counterpart to these collage paintings. For that project, and in general, he likes to work with samples. His views on the use of material pretty much echo what I did. He also processed music and sound that was generally present and he was unafraid of trash. In this box, you wear headphones and are buckled up on that revolving chair, and it becomes very narrow; it’s supposed to be a claustrophobic version of the chapel, like some kind of psycho tank.

HUOFor one person—you can only be inside alone. The chapel for the Serpentine is completely different, in that it will comprise paintings made here in Ispaster in the Basque Country. You told me in our last conversation that their origin was this John Graham painting (Tramonto Spaventoso, 1940–49). Graham (1886–1961) was a modernist painter born in Russia, who has somehow been forgotten. There’s a strange amnesia about him. In your Fabric Paintings catalogue, John Corbett writes that you first read about him in a biography about Jackson Pollock. Can you talk about Graham? How did you come to that painting and how did it trigger not only these new paintings, but also a whole line of older paintings that we’re including in the exhibition?

AOThe fascination with Graham came from a strange statement in this Pollock biography Jackson Pollock: An American Saga (1998) by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith. These are the people who also wrote this super-boring Van Gogh biography, Van Gogh: The Life (2011). But the Pollock book isn’t boring at all; it’s extremely good. What I liked so much about this book was that they absolutely leave it open to interpretation whether they consider Pollock to be a bit of an idiot. They describe very nicely how the meaning of Pollock lies in the entire picture—so not as the single accomplishment of a genius, but also in relation to luck and the fortuitous influence of Clement Greenberg and others. And it’s all of these elements combined that results in the importance of Pollock; it’s not just the result of the huge efforts of a genius. Related to that, Graham played the role of mentor to Pollock, as an opposing and interesting figure. I find it so interesting that with Pollock’s work, something of enormous importance emerges as an objective final result, as something that’s there, no matter how it came about, which simply has an enormous meaning.

Installation view, Albert Oehlen, Serpentine Galleries, London, October 2, 2019–February 2, 2020. Photo: readsreads.info

Installation view, Albert Oehlen, Serpentine Galleries, London, October 2, 2019–February 2, 2020. Photo: readsreads.info

HUOIt’s only a short phase, a sort of flare.

AOYes. It’s basically an appearance flashing up, mainly in the big, classical paintings that hang in museums, like the ones in the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In contrast, Graham as a person was very smart and good at expressing what he’d learned in Paris.

HUOSurrealism.

AOYes. First, he was a rather clunky Picasso imitator. Later he made a couple of fascinating and disturbing women portraits. Not only because they are cross-eyed.

HUOYou bought one painting, which is the trigger for this whole exhibition—for the new work, but also for many of the older paintings that will be included. Even so, we’re not sure if we want to hang this painting in the exhibition.

AOYes. The trigger wasn’t my interest in Graham himself, but the painting. I’d found a black-and-white image of it in Dore Ashton’s book The New York School (1992). My first thought was that it was a really shitty painting. I found it spectacularly bad. It’s chunkily painted, possibly unfinished. The content triggers a certain depth, but without resolving anything. I am not interested in meaning. I am unable to read paintings and understand the meaning. It is alien to me. It has the appearance of wanting to tell you something extremely important.

HUOWhat is the message?

AOI don’t know, but something is supposed to come across with this painting. There are connection lines and suns and triangular swastikas—three-armed ones. I don’t know what they’re supposed to be. They could also be running suns. They have the beards and glasses of very wise historical figures. I don’t know what to associate them with. I found it quite funny that I wasn’t able to make sense of it at all. I also didn’t want to. I thought it would be interesting to research what it could be through my own experiments.

HUOAnd that’s how the paintings emerged over the years?

AOYes. It’s some kind of vehicle for me. It’s like a construction kit of motifs. It’s actually one motif, but with various elements that are different in nature. It goes from the graphic to the picturesque. That means there are parts that prompt you to paint more, to become more plastic. Then there are others with a big letter and smaller text and a wooden bar. There’s a head with a pilot hat and goggles. But there could also be a third eye, rays and lines going into the depths, like in Dalí, or the wooden planks that we find in Jörg Immendorff paintings.

HUOThis movement from the graphic to the picturesque is interesting. Your triptychs emerge from this. You always made big drawings—your show at Palazzo Grassi (April 8, 2018–January 6, 2019) included large-scale black-and-white etchings. But here for the first time the graphic becomes picturesque—big drawings become paintings. There’s even a triptych that’s purely graphic; in another there’s a big drawing. Can you say something about this?

AOThe big drawings or things on paper I’ve made are inspired by Konrad Klapheck’s studies, which he always makes for his paintings. But Klapheck did them on canvas, which I haven’t seen before. Within this, I found a prompt: what if I made a charcoal drawing in which every crumb is controlled and goes exactly where I want it to go? That’s very different from the association you have with the charcoal drawing, where you imagine the wine-drinking, bearded, shaggy artist giving his inspiration free rein with abrupt movements. You always imagine charcoal drawings as dirty—at least from the last hundred years.

HUOBut here they’re the opposite of dirty. It’s all so organized. I made a book with Klapheck in 2006 (The Conversation Series, volume 3). It’s a very controlled order with him.

AOYes. There’s no impulsiveness with him.

HUOWith you, it’s controlled as well.

AOYes. At least in the drawings. I bring the charcoal to the paper or canvas in a clean way. So it looks different from the usual charcoal drawing, because it becomes like painting. I clean while doing it. I manipulate. I erase. I edit it so that it’s completely controlled. Klapheck didn’t do that. When he corrects something, you can see that there’s a correction. That’s the idea, an aesthetic idea: to make a piece of art where the charcoal sits exactly there and frays or not as you want.

Albert Oehlen in his studio, Ispaster, Spain, 2019. Photo: © Esther Freund

HUOThat’s one part of the exhibition—these incredible charcoal drawings. However, there are also paintings. They’re triptychs as well. Can you say something about the genesis of this chapel for London?

AOThese big charcoal pictures are combined or fit together with large watercolors on canvas. Watercolors are also normally small, but here they’re made big. It’s nothing—I don’t have to praise myself for doing this. It was just fun for me to do it.

HUOBut it normally happens on paper; here, it happens on the canvas. The reference to Surrealism is interesting, too. Glenn O’Brien wrote: “There’s no reason Surrealism should be finished any more than realism should be, or romanticism or bagism or fagism. Albert Oehlen is a Surrealist, practicing very much in the Paranoiac-critical method as developed by Dalí, with post-cubist spatial displacement.”2 And Surrealism also plays a role with Graham. He emerges from Surrealism. Surrealism also plays a role with Pollock. I knew Roberto Matta at the end of his life. I did long interviews with him. And Matta influenced them all. Matta influenced Graham, Matta influenced Gorky.

AOExactly.

HUOWhat does this exhibition have to do with Surrealism?

AOSurrealism, for me, is the most interesting art style of the past century. I’m interested in that moment of Surrealism when artists, writers, or whoever approach this toolbox. I don’t care about the frottage of Max Ernst or the importance of dreams, fantasy, and the unconscious. I’m more interested in that point when Dalí comes up with something funny and claims that it comes from the subconscious. That’s what I admire. I want to approach that method. From what I’ve read about Surrealism, the most important books are Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton (1995) by Mark Polizzotti and Dalí’s The Secret Life. I keep realizing that this is also the origin of Conceptual art, and the most important forge of ideas.

HUOSurrealism as forge of ideas?

AOYes.

HUOCan you say something about this new triptych, with these watercolors? There’s only one drawing. How did these motifs come to life?

AOThey all derived from this Graham painting.

HUOIncluding the figures?

AOYes. Well, they look completely different now.

HUOAnd those heads are from Graham, too?

AOYes. I found out after twenty years of research that the name of this painting is Tramonto Spaventoso [Terrifying Sunset]. The sun sets in a sort of zigzag, not in an arch, with abrupt, crisscross movements. On the right side of the painting there’s a mermaid. The pilot-like man is staring at her breasts.

HUOCan we discuss the decades of works connected to this Graham painting? Which works are most important to you?

AOI can’t really say much about that. What’s nice for me about getting these pictures together is that they’re from different times and were always an opportunity for me to relax. I risked quite a lot in these paintings. I think that if you’re willing to look at my things, there’s a high entertainment value.

HUOParadoxically, because of the restriction in this one painting, there’s a lot of freedom.

AOI think it’s become an entertaining story.

HUOThere are always figurative elements.

AOIt’s always the same repertoire, which is being overstretched in all directions.

HUOYes, in that sense it’s infinite.

AOTheoretically, yes.

HUOI saw this exhibition of your gray paintings in 2017 [Nahmad Contemporary] in New York. It was interesting to see these gray paintings, made from 1997 to 2008, all together for once. The group of works that come from the Graham painting is not such a clear group like the gray paintings.

AOIt’s connected more content-wise, not via the motif and the way it’s painted.

HUOIn that way it’s different from the gray paintings.

AOExactly. Here you have the only motif that’s continuously present in a larger group.

HUOAnd the gray paintings are completed?

AOYou never know. But let’s say yes.

Installation view, Albert Oehlen, Serpentine Galleries, London, October 2, 2019–February 2, 2020. Photo: readsreads.info

Installation view, Albert Oehlen, Serpentine Galleries, London, October 2, 2019–February 2, 2020. Photo: readsreads.info

HUOWith the Graham paintings, the restriction to one painting gave you freedom. With the gray paintings, it’s a restriction to one color. How did that come about?

AOIt was super simple. I was thinking about Gerhard Richter, and about his blurring of black-and-white paintings. I simply wondered how it would be if you blurred in all directions. What happens then? I mean, Richter did that as well, although he’s a bit more systematic. With me it’s different. When I have a conceptual idea, I don’t realize it immediately. I look where I can gain something. And that’s the difference from Richter.

HUOSo, you don’t work systematically?

AOI also don’t stick to the requirements. I’m happy about the requirements, but I don’t have to stick to them if I don’t feel like it anymore. Now I’m telling all my secrets!

HUOThat’s good. But you’ve also said that with the gray paintings, you self-prescribed, like a medical prescription, these gray colors as therapy to increase the longing for color.

AOYes, that’s right. That’s a side effect.

HUOBack then in New York, when I saw this exhibition, I asked myself, how did it come to an end, in 2008, this apparently infinite series?

AOI didn’t feel like it anymore.

HUOIt just ends?

AOYou do something different.

HUOBut with this John Graham painting, it keeps giving you desire.

AOThat also went quiet for a certain number of years.

HUOHow did it return? Did it happen suddenly?

AOThat was in Los Angeles. I’ve no idea how it happened. I didn’t know what to start, and then I thought, “Ah that! I’ll try it out. It’s certainly easy.”

HUOWhat made you switch from oils to watercolor and charcoal in these works?

AOIn comparison to my colleagues, I have a relatively small studio. Which I like, but over a longer period, I’ve started to paint more and more fluently. Fluency with oil painting means more turpentine and more smell. At some point I got really mad. I didn’t want to smell it anymore. I also looked at oil paint suspiciously. Even worse, I developed a real reluctance. That’s why I did this charcoal and watercolor thing, because I didn’t want to smell that anymore.

HUONot Serpentine, but turpentine!

AOExactly. I was in the middle of some large-format abstract oil painting. Suddenly I stopped, because I couldn’t bear to smell it anymore. I like having a reason for something. It’s nice. Because then you don’t need inspiration. You simply have a reason.

Albert Oehlen in his studio, Ispaster, Spain, 2020. Photo: © Esther Freund

HUOSomething we haven’t covered is the role of collecting. When I visited you for the first time in Gais, Switzerland, I realized that there’s a lot of art in your studio by students, colleagues, older artists, including a de Kooning painting. Can you say something about this idea of collecting and art made from art?

AOYes. Art is made from art. I feel that way. It’s nicer to own a piece of art than a share. Therefore I bought some when I had money. It began by trading with Kippenberger, and Werner Büttner. Kippenberger was a role model because he was so greedy.

HUOHe was greedy for other art?

AOHe was greedy in every way. I understood how this supposed deadly sin could actually be a good thing. Somehow I realized that it’s fun. Then I began to acquire art pieces. It’s a gesture of trust towards the person you’re buying from. If it’s a young person, it’s nice, they’re happy. You can consider yourself smart and say they’re going to be really huge one day. It has many nice aspects. You can hang it on the wall and be pleased with it. Basically this happens when you see something of meaning for yourself. You consider yourself smarter than other people and ask yourself, “Why don’t they see it?” It’s all lots of fun.

HUOIn your studio in Gais, there was also an André Butzer painting. He’s a younger artist you’re supporting.

AOYou can’t call it “support” because he’s an established artist but I got to know him very early on.

HUOAnd here in the Basque Country, there are also works of younger artists in your studio. While this cycle for the Serpentine is being created, young artists are painting in your studio. You say that you’re often surrounded by artists. The studio isn’t very big. You don’t have many assistants. It’s not a factory. It’s an exchange of energy with artists. Can you say something more about that, because it’s quite uncommon?

AOWell, yes. I like being alone in the studio. I always work alone basically. But every now and then I have people around who help me. I can put the paintings up myself. It’s no problem for me at all. I can carry them by myself. I can do everything. But sometimes I get mad and like to have people around to talk to. From their facial expressions, I can tell how they’re reacting to what I’m doing. I like that. It’s even better when they do something themselves. Then it’s not a situation where you pay someone to give you answers. It’s mutual. That’s especially nice. I hope it’s beneficial to them as well.

HUONow that the chapel has been built, do you have any other unrealized projects?

AONo. I’m glad to have anything at all. One or two years ago, I thought, everybody has something they dream about, where they say: “I want to make the largest whatever, I need that museum or just I want more money.” But I don’t have anything. There was a total emptiness. I thought, I don’t want anything, or need anything. I just want to paint the next painting. I don’t even have a series or a project in mind. Now, I’m happy to at least have the chapel.

Artwork © Albert Oehlen

Text originally published in Albert Oehlen, exh. cat. (London: Serpentine Galleries and Koenig Books, 2019); Albert Oehlen, Serpentine Galleries, London, October 2, 2019–February 2, 2020

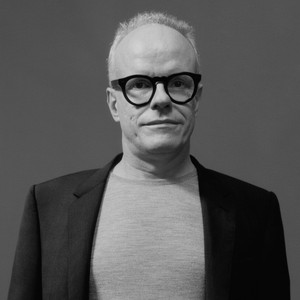

Hans Ulrich Obrist is artistic director of the Serpentine, London. He was previously the curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show), in 1991, he has curated more than 350 exhibitions. Photo: Tyler Mitchell

Albert Oehlen’s oeuvre is a testament to the innate freedom of the creative act. Through expressionist brushwork, surrealist methodology, and self-conscious amateurism he engages with the history of abstract painting, pushing the basic components of abstraction to new extremes. Photo: Oliver Schultz-Berndt

The artist speaks with Mark Godfrey about his new paintings, touching on the works’ relationship to John Graham, the Rothko Chapel, and Leigh Bowery.

The Summer 2021 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Carrie Mae Weems’s The Louvre (2006) on its cover.

Albert Oehlen speaks to Mark Godfrey about a recent group of abstract paintings, “academic” art, reversing habits, and questioning rules.

This film by Albert Oehlen, with music by Tim Berresheim, takes us inside the artist’s studio in Switzerland as he works on a new painting.

The artist met with art historian Christian Malycha to discuss his newest paintings.

The Fall 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Sinking (2019) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn on its cover.

At the Palazzo Grassi, Venice, a career-spanning exhibition of paintings by Albert Oehlen, entitled Cows by the Water, went on view in the spring of 2018. Caroline Bourgeois, the curator of the exhibition, discusses how the show was organized around the artist’s relationship to music.

Join Gagosian for a conversation between director, producer, and writer Sophia Heriveaux and actor, director, and writer Roger Guenveur Smith inside the exhibition Jean-Michel Basquiat: Made on Market Street, at Gagosian, Beverly Hills. Heriveaux and Guenveur Smith both share a personal connection to Basquiat: Heriveaux is the artist’s niece and Guenveur Smith was one of his friends and collaborators. The pair discuss Basquiat’s work and legacy, as well as his lasting impact on contemporary art and culture.

Join Brooke Holmes, professor of Classics at Princeton University, and Lissa McClure and Katarina Jerinic, executive director and collections curator, respectively, at the Woodman Family Foundation, as they discuss Francesca Woodman’s preoccupation with classical themes and archetypes, her exploration of the body as sculpture, and her engagement with allegory and metaphor in photography.

In conjunction with Marks and Whispers, at Gagosian, Rome, Oscar Murillo and Alessandro Rabottini sit down to discuss the artist’s paintings and works on paper in the exhibition, as well as how the show emphasizes the formal, political, and social dimensions of the color red in Murillo’s work of the last decade.

In this video, Gagosian presents a conversation between Jordan Wolfson and Johanna Burton, Maurice Marciano Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. The pair discuss Wolfson’s animatronic work of art Body Sculpture (2023).

Gagosian hosted a conversation between Louise Bonnet and Stefanie Hessler, director of Swiss Institute, New York, inside 30 Ghosts, the artist’s exhibition of new paintings at Gagosian, New York. The pair explores the work’s recurring themes—the cycles of life, continuity and the future, and death—and discuss how the conceptual and pictorial structures Bonnet borrows from seventeenth-century Dutch still-life painting converge to form a metaphor for hard labor, basic animal urges, and the things we often try, but fail, to hide.