Mark Godfrey is an art historian and curator based in London. From 2007 to 2021 he was senior curator of international art at Tate Modern, London, where he curated and co-curated retrospectives of Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, Alighiero Boetti, Franz West, and others, as well as the acclaimed exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power. He is currently working on projects with Anicka Yi, Laura Owens, and Jacqueline Humphries.

Albert Oehlen’s oeuvre is a testament to the innate freedom of the creative act. Through expressionist brushwork, surrealist methodology, and self-conscious amateurism he engages with the history of abstract painting, pushing the basic components of abstraction to new extremes. Photo: Oliver Schultz-Berndt

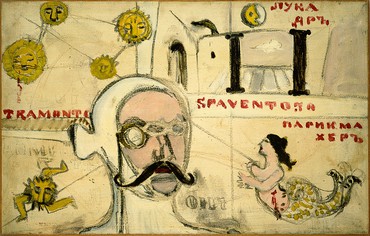

Mark GodfreyYou’ve been interested in John Graham [1886–1961] for a long time and started making works that riffed on and remixed his painting Tramonto Spaventoso [Terrifying Sunset, 1940–49] after you discovered an image of it in Dore Ashton’s book about American abstract painting many years ago. But what made you come back to that painting in the body of work that you have been making within the last two or three years? Why did you return to Graham after a period where you hadn’t looked at him?

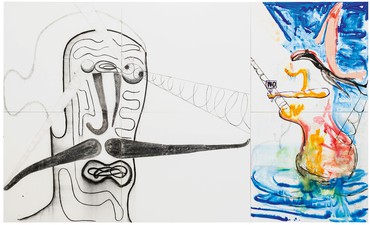

Albert OehlenI was experimenting, and I had several things in mind, and one was trying to make a large charcoal painting—not drawing, painting. And that had started with the charcoal drawings, the large ones. I needed a motif to find out what happens, and I just picked that one without thinking much, and then it turned out I got hooked and couldn’t stop.

MGHow long had it been since you’d last used that motif?

AOIt might’ve been ten years or more.

MGWhat made you want to make a large charcoal painting at that point? Was it just sort of an interesting question about how to make a drawing that’s a painting?

AOYeah, exactly. With the large charcoal drawings on paper, I discovered several things you can do with that material—how it looks and what it does—and that got me interested in trying more and in trying the same thing on canvas.

MGWhen you draw in charcoal on a smooth piece of paper, it obviously sits on the surface differently from when you put it on a canvas that’s been prepared and gessoed. This is a very techy question, but what different surface effects will you get when it’s on a canvas?

AOYou can use water—and I thought that was very interesting because you can very easily get different shades of gray. When you have that result and see some of the drips there, it’s funny because that’s so typical of painting.

MGIs making a huge painting in charcoal another way of disobeying the rules of painting? Because I think there’s always been a traditional hierarchy between drawing, which is seen as preparatory and a more minor work, and painting, which is the finished major work.

So when you make a huge charcoal painting, you’re kind of interrupting painting, which should have oil on it but instead it’s got charcoal. Was that one of your intentions?

AOYeah, that’s what happens. I’m not the first one to do this. [Konrad] Klapheck has always made his sketches the same size as his paintings. Most of them are charcoal on canvas—of course, they look very different. But I thought that those paintings were very impressive. And I thought I had enough reasons to do it . . .

MGSo, if I understand correctly, you were wanting to experiment with making a charcoal painting and you were looking for a motif and the thing that came to mind in some way—almost because it’s in your hard drive, in your memory—was the John Graham painting that you’ve been fascinated with for a long time. And Graham was a contemporary of [Mark] Rothko’s but made work that was obviously very different from Rothko’s. At what point did you start to think about putting together the remixes of Graham’s painting with the format of the Rothko Chapel in your own Tramonto Spaventoso [2019–20]?

AOI don’t know, just while I was making the work. I thought it was an interesting idea to have that aim—like now I have to do this, I have to follow these formats, and how do I compose it, how much material do I have, and all these questions. It was challenging. I just needed something to do [laughs].

MGWhen I went to Houston, I was really excited to visit the Menil Collection and see the Rothko paintings in the chapel. And I don’t think I’ve ever had as disappointing an experience of art as that visit—partly because I really couldn’t see much in the painting. There was also some guy in the middle of the chapel doing yoga, not looking at the paintings—it felt like this person had been told he could have a spiritual experience in the middle of these Rothko paintings, but he wasn’t actually looking. I remember his eyes were closed—like it’s all about the suggestion, you know, that you can go to this place and have an experience.

But I was profoundly disappointed with the surfaces. Maybe they’ve changed over time. Have you been, and what was your experience of that place?

AOIt was similar. In the books on Rothko, it always says the colors have changed because he used a mixture of materials and didn’t care if it was good stuff. Anyway, when I got there, it was so dark, and I couldn’t see anything. And I thought, It’s funny, I don’t want to judge it, but if I sit here and just let this make an impression on me, there must be a lot of auto-suggestion working, because otherwise you don’t get a result.

And so, with that impression, I thought that there is a kind of funny tension between my motifs and that installation. But also, right in the beginning, when you see that group of painters in the 1940s, they all were like—I mean, Graham was connected with [Arshile] Gorky and [Willem] de Kooning and was advising them—he had a lot to say. But his own works were absolutely not going in that modern direction, into what would become classical abstract paintings. And especially the painting that I’m referring to, Tramonto Spaventoso, seems to have an overload of meaning. From my point of view, it’s kind of ridiculous because I’m not interested in meaning at all, or how to transmit meaning in a painting. I especially can’t stand it if it’s like encoding and decoding, if that’s what you’re meant to do with a painting or a piece of art.

MGDo you think that Graham had a set of meanings that he wanted to be communicated with that painting, or do you think he was playing with the idea of meaning?

AOAll of that is possible. I don’t know. The original painting is loaded with symbols. It almost looks like a puzzle, you know, like a drawing puzzle.

MGBut it may be a puzzle that can be solved. The mermaid and the self-portrait and the sort of swastika and the sunset and the words and the Russian writing and the Roman writing—it may be that, in his mind, he thought they all connected to produce something that added up. Or maybe he thought they didn’t connect and that it was a kind of game being played with the viewer, who would have a desire for them to connect, but they didn’t. I don’t know enough about Graham to know what—

AOYeah. I don’t know. He has these repeating motifs, like the cross-eyed ladies, and some of them have a wound on the neck. In one painting, he even painted the wound with the knife sticking in it [laughs], and it’s kind of perverse. But I’m so ignorant—I don’t even try to find out what a painting means. Never. I don’t care. It can take twenty years until I see, Oh, this is that figure repeating and he’s doing that. Because I absolutely don’t care.

MGJohn Corbett, who’s a friend of yours from Chicago, writes about your early series of Graham paintings through the lens of the remix. And, you know, the remix takes you to dub DJs producing a new version of a reggae track, or house DJs taking a disco track or a funk track from fifteen years before and remixing it.

But there’s also the idea of the mash-up—two completely different songs that are mixed together. One of my favorites—and this is quite old—was when someone put a George Michael song and a Missy Elliott song together. And what’s always amusing about mash-ups when you’re on a dance floor is how the two things are incongruous and there’s a certain pleasure you get from hearing one thing that’s sort of cheesy and another thing that’s cool, but together they’re great.

So I was wondering, when you put the Rothko Chapel and the John Graham painting together, does that come out of your own interest in experimentation in music?

AOMaybe that kind of attitude or humor that I find in some of the music, maybe I adopt that or try to do something like that, but unconsciously. You mentioned these musical mash-ups—have you heard about the shred videos?

MGNo.

AOIt’s super interesting. They are these videos that were circulating online around ten years ago. This guy picked videos of famous musicians like Santana playing, and overdubbed the footage of them shredding with audio of his own playing, as bad as possible. He played only whatever instrument you see being played on the screen—so whenever you don’t see the bass, you don’t hear the bass. Everything you do see, he replaced the sound for, and he can play, but he is intentionally playing it badly. It’s incredibly funny. And it makes you wonder why—it has this effect, like this relation of sound and image. So that is something that I think about.

MGYou first showed a group of these works at the Serpentine Galleries in London and now you are showing the remaining four panels at Gagosian in Los Angeles. Many people will recognize the format and scale as that of the paintings in the Rothko Chapel, and so there is that same kind of amusement, I think, that the imagery in your works is the very opposite. Inasmuch as the Rothkos, at least in my experience, give you very little to see, in these paintings of yours there’s almost too much to see. It’s hard to think that you’ve seen the whole painting because there’s so much going on.

AOExactly—it’s kind of absurd. And I like that—that’s part of the idea, to see it from the other side.

MGWhat did it feel like to make works that are this massive? Some of the new paintings are four and a half meters tall.

AOYes. It’s terrible [laughs].

MGWhen you’re on your own in your studio in St. Gallen [Switzerland], you make paintings that are more like two meters tall because they’re easy for you to carry around the studio by yourself if you want to. But when you embark on these larger paintings, you need to build a scaffold, you need to have a ladder. Maybe you need assistants. What was it like for you to make such big paintings?

AOI could have done them alone, but it would’ve been hard. And it was hard to work that large—I worked on the floor, and then some have two parts. There were a lot of technical difficulties—they’re heavy, and difficult to carry around. It would’ve been possible to do alone, but not so much fun. It was fun, for this limited group, to have these challenges and have these problems and solve them. But if I were to only paint that large, I would not enjoy it. So I was happy when I had it done.

MGWe talked about the charcoal, but in one of the paintings, there’s a fabric, in kind of a floral chintz design. You used fabric in the 1990s, but—obviously, it’s the art historian in me, and also knowing of your training in Hamburg—it’s hard for me to look at that painting without thinking about [Sigmar] Polke and the way that he used these sorts of cheesy decorative fabrics as the beginnings of his paintings. When you decide to use fabric—which you hadn’t done for a while—do you see that as a deliberate gesture toward Polke, or is it just another material?

AOWhen I use this fabric and think of Polke, it’s rather a test of courage for me if I still can do it. Because normally I would shy away from that and say Polke made great paintings that way and I shouldn’t come near it. But with the earlier group where I worked with these, I thought I had such a strong idea that I could do it. Of course, a lot of people will say, “Ah, he was a student of Polke’s, and now he works like Polke.” But I said to myself, I don’t care, I’m going to prove that I can make my own paintings.

In the case of that painting, I just had an idea and I wanted to make that one exception in that group. I had found some images of Leigh Bowery and I was so impressed by this guy. He was incredible, and I wanted to make a reference to him, to have Graham as Leigh Bowery. That’s why he has this fabric—it’s this thing that Leigh Bowery had all over his face, you know, where the dress goes up over his face.

MGHave you been interested in Leigh Bowery’s work for a long time? He’s such an amazing figure.

AONo, I haven't. I just learned about it within the past year or so and I’m very impressed.

MGHe did so many interesting collaborations, with Michael Clark and with Lucian Freud. And he had some great lines about how the dressing up is more important than the going out.

AOYeah, yeah [laughs].

MGTell me about the two huge paintings that are more abstract than the others, where the image of the self-portrait doesn’t appear. Are those two paintings still based on motifs from the Graham painting?

AONo. Maybe the first one, when I prepared for it, maybe that came from there. But the reason why they’re there . . . It’s kind of a statement about two things that I believe in. One is that everything is abstract anyway [laughs], so, yeah, what’s the difference? I mean, I know there is a difference, but still, I want to put it all on the same level.

The other thing is if you do something figurative and it goes out of control, then you can still make an abstract painting out of it [laughs]. And I love to see abstract paintings in that light—like what if the painter wasn’t able to do something figurative, he couldn’t get it done, or he couldn’t get the painting done. I like that idea.

MGIn the corner of one of them, there are some marks that look to me like they’ve been printed, almost like they’re footprints.

AOThose are footprints.

MGWere these made on the floor mainly, or on the wall above?

AOBoth.

MGI understand that these works were made in Ispaster, Spain. When you’re working there, do the different light conditions at the studio affect the outcome? Being able to move from Los Angeles, where you had a studio for a while, to St. Gallen, and to Spain, when you look at your work, do you know immediately that something was made in a specific place?

AOI remember it. If it’s the light, it just means there’s more light in one place than in the other. And more light is good. But it’s more about the atmosphere—how I feel in that place, in that city or whatever. In one place, I’m more generous than in another one. I’m definitely less generous in Switzerland. The atmosphere in Switzerland is not telling you to go crazy. It’s not saying that.

MGSo do you think you’re done with the John Graham painting?

AOI hope so [laughs]. I think I’m done with it, yes.

MGTramonto Spaventoso is a weird obsession that keeps on coming up. Is there anything else that has fascinated you to that degree?

AOThe other thing that still comes back from the past is the tree. For me, the tree is still an unsolved problem [laughs].

MGI hope the tree will be unsolved for all artists forever. It should always be unsolved.

All artwork by Albert Oehlen © Albert Oehlen