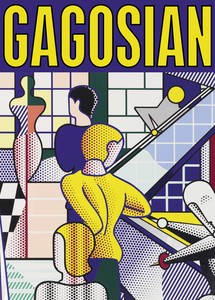

Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2024

The Summer 2024 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail of Roy Lichtenstein’s Bauhaus Stairway Mural (1989) on the cover.

Spring 2021 Issue

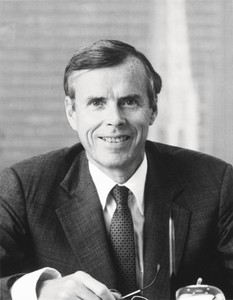

Jacoba Urist profiles the legendary collector.

Donald Marron, c. 1984. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Donald Marron, c. 1984. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

It’s been said that serious art collectors tend to fall into four tribes: the enterpriser, with roots in the Medici tradition of patronage; the connoisseur, the market’s intellectual buyers; the trophy hunter, for whom acquisition is an end in itself; and the aesthete, for whom art is an emotional extension of their being.1 Ask Artnews-top-200 collectors about their motivations and methods, and their tribe is often immediately apparent. But through a series of phone conversations, interview transcripts, and essays, the late financier/philanthropist Donald Marron—who assembled a museum-caliber collection of postwar art over six decades—emerges as a collector from a lost era, possessing an almost boyish devotion, an inveterate openness, and a democratic ethos. Everyone’s opinion resonates, no matter what background they come from. As Marron’s private curator Matthew Armstrong said last August, in addition to talking with expert curator-friends such as John Elderfield, Robert Storr, Ann Temkin, and Kirk Varnedoe, Marron would often ask nonart people, like folks at his office, what they thought of a piece, interested not so much in scholarship as in talking with those who could “see a little beyond the frame . . . [and] compelled you to think more dramatically.”2

Marron put together an unparalleled private collection of twentieth- and twenty-first-century paintings, drawings, and prints. The roster of nearly 300 works is a veritable tour of the Western canon, ranging from major works by Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso on through Lee Krasner, Willem de Kooning, Ellsworth Kelly, Cy Twombly, Agnes Martin, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, Gerhard Richter, and Mark Grotjahn. This spring Phaidon will publish Don Marron: Chronicle of Collecting, a book surveying not only a far-ranging passion but a courageous and lifelong evolution of taste. Yet even within New York’s art bubble, Marron remains enigmatic, a cognoscente of fairly humble origins who rose to champion future marquee artists before they were household names and to head the board of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), donating some 500 artworks to the institution, assisting it in multiple expansion projects, and becoming a trusted confidant for its curators. What kind of collector was this visionary, who left an indelible cultural mark on the city he credited for his success?

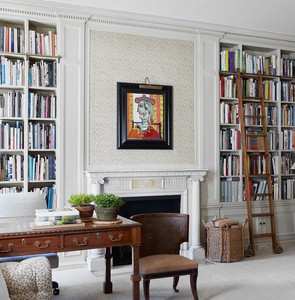

The Marron family’s apartment, New York. Photo: © Ngoc Minh Ngo

“There was an innate respect and love and appreciation of the art, but at the same time, art wasn’t placed in a situation where we revered it or understood its significance,” Don’s son William Marron tells me of the childhood he shared with his sister, Serena Marron. While certain works stayed with them throughout their lives, walls in their apartment were rarely static; “Growing up,” he says, “this allowed you to have your own individual reactions to the different works, rather than to be drowned in the history and the value of them.”3 William recalls his parents encouraging a warm, boisterous home, with plenty of roughhousing and antics, often in uncomfortable proximity to irreplaceable masters, flirting with catastrophe. He, Serena, and their friends would ride Razor scooters through the rooms and hallways and he spent endless hours bouncing a tennis ball, an easy ricochet into a painting. He remembers one close call when, carrying a snack from the kitchen back to his bedroom, he tripped and a dab of ketchup landed on an artwork. “I grabbed my dad from his room,” he says with a chuckle. “He was very reassuring and relaxed. It constantly seemed like we were having these little misses, and they always worked out fine from a preservation perspective. My father trusted us, but I also think he trusted the art.”4

Despite Don Marron’s depth of knowledge about art, he wasn’t a scholar by trade; his joy came from the natural reflex to a captivating work, the visceral connection to beauty—the hardest reaction to achieve. Marron considered art one of the most visible aspects of genius, though he increasingly felt that painting was moving away from aesthetic beauty toward an agony of emotion.5 Pace Gallery founder Arne Glimcher tells the story of Marron’s Cézanne watercolors, studiously protected from light in a folio that he occasionally removed to “share their beauty” with a friend: Don always knew that he was only the custodian of these treasures for a limited time, remembers Glimcher.6

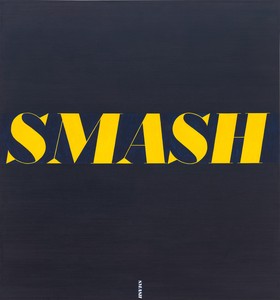

Ed Ruscha, Smash, 1963, oil on canvas, 71¾ × 67¼ inches (182.2 × 170.8 cm), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Gift of Helen and Charles Schwab through The Art Supporting Foundation. Artwork © 2021 Ed Ruscha. Photo: Katherine Du Tiel

Gerhard Richter, Helen, 1963, oil on canvas, 43 ⅜ × 39 ⅜ inches (110 × 100 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Gift of UBS. Artwork © Gerhard Richter 2021 (0001)

“Every time we left a gallery, or a new museum, or someone’s house, or a fair, he’d always try to talk about our reactions, how I felt about the artwork,” explains William Marron. “We wouldn’t necessarily get into too much intellectual detail.”7 In this way the collection emotionally bound Marron to his offspring—which is not to say that every piece that circulated through the family’s life elicited a sanguine response from the children, or that his father expected one. As a kid, William was unsettled by a certain Roy Lichtenstein; something about a particular canvas the family owned—mainly, the exaggerated teardrop in the woman’s eye—unnerved the young boy in a way he couldn’t quite articulate. In contrast, he found himself intimately drawn to Mark Rothko’s No. 22 (Reds) (1957), and credits his father’s patience with guiding him to see Abstract Expressionism. Serena Marron for her part was inspired one year to celebrate their father’s birthday by painting a book of meticulous miniature copies of all the works of art in the house, and she has spent several afternoons since his unexpected death creating her own versions of some of the masterpieces.8 “Don understands the value of art,” emphasizes Larry Gagosian: “that it makes kids dream, that chasing it quickens your pulse, that its presence nourishes a community.”9

Roy Lichtenstein, Mirror #10, 1970, oil and Magna on canvas, diameter: 24 inches (61 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Gift of UBS. Artwork © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. Photo: courtesy Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Reflecting on how his affaire de coeur with modern art began, Marron confessed to a MoMA oral historian, Sharon Zane, that he hadn’t been an especially visual child, but felt that after decades of collecting he had developed an unusual memory for images. “I think many collectors have this,” Marron explained. “They’ll show me a picture and I’ll say, ‘I know I’ve seen that somewhere before.’ And sure enough, I’ll go back and there it is.” A consummate New Yorker, he remembered that the first time he was overtaken by an artwork was as a teenager in what he dubbed the “1911 room” at MoMA, a Cubist gallery of Picassos and Georges Braques. “I couldn’t stay very long,” he reminisced. “It just made me so excited to be there and to see those pictures.” Marron elaborated on that formative visit in conversation with Michael Shnayerson: “It was the power of the composition, and the feeling that you were seeing something that hadn’t existed before.”

Marron’s next crucial encounter would come years later, when, newly married to his first wife and in need of art for his apartment, he discovered Hudson River School painting from the mid-nineteenth century. The period certainly appealed to him but also had a great benefit for a first-time buyer: relative affordability. “In a very modest way that was my first collection,” he would remember. “We bought a marvelous, little, teeny [Albert] Bierstadt of a boat on the water—a very small Bierstadt, maybe 6 by 9.” 13 From there, an exhibition of monochromatic prints in East Hampton’s Guild Hall ignited a serious interest in lithography, which eventually led to a visit to the Los Angeles print workshop Gemini G.E.L., on a day when they were making Frank Stella’s River of Ponds series (1971). “I knew nothing about contemporary art at that time, and I was just stunned by how great they were,” explained Marron, who eschewed popular criticism of lithography’s overcommerciality and believed that the more you understood the technique of contemporary printmaking, the more you appreciated the art form.14

Works of art, Marron well understood, often reveal themselves slowly, through patience and discipline.

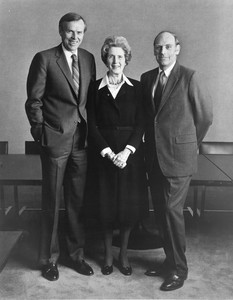

After becoming fascinated by prints, Marron gradually earned an invitation behind Leo Castelli’s velvet rope, a literal as well as metaphorical hurdle to a space reserved for the legendary dealer’s favorite collectors and latest offerings. Even as PaineWebber CEO from 1980 to 2000, Marron spent countless Saturday afternoons in Manhattan galleries, perennially on the hunt. MoMA director Glenn Lowry reflects on his visual methods in Chronicle of Collecting: “Don never rushed to judgment and would return often to a painting or drawing that appealed to him, questioning its qualities over and over again . . . he had the rare ability to be comfortable in his uncertainty, to not feel that he had to make a firm decision before he was ready to do so.”15 Works of art, Marron well understood, often reveal themselves slowly, through patience and discipline. In Lowry’s view, it was an uncanny ability to examine art in a dispassionate way that distinguished Marron as a collector, testing the confines of his own taste time and again. And “when Don married Catie, she quickly became an important part of the decision-making process in their collection,” recalls Bill Acquavella. “There was not a painting in their apartment that both of them did not want to be there. The combination of Don’s and Catie’s eye helped to create one of the great collections.”16 In fact, without Marron’s eye, MoMA would look quite different from the way it does today: appointed to the museum’s board of trustees in 1975 and becoming president of it a decade later, he oversaw its third expansion project. In 1984, the Modern more than doubled its gallery space and added an auditorium, two restaurants, and a bookstore in an expansion designed by landmark architect César Pelli. “You had to persuade the city, the state, you had to raise the private money to handle our share of financing, you had to work closely with the curators and staff of the museum to make sure that what you wanted was possible,” Marron told Zane. “And you had to do all of that with the serious limitation that you didn’t have any more space, that you had to do this on the existing footprint of the museum. And there was one absolute rule for us, which was, we could not touch the [sculpture] garden.”17 So began an odyssey for Marron and the board, as they navigated architectural, financial, and zoning hurdles to reimagine not only a museum but a cityscape central to his identity. “My view is that New York City is heavily dependent, for its success and leadership, on tourism,” Marron said in 1994, words that echo more powerfully post-covid. “Expanding a great museum is important,” he added, because New York is “considered not only the financial capital of the world, but one of the two or three arts capitals of the world.”18

Left to right: Don Marron, Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller, and Richard Oldenburg, at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1984. Digital image: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Evelyn Hofer, Photographic Archive

Central to Marron’s vision was the idea that art belonged not only in homes for a family to savor, or in museums to arouse a wide public, but in corporate settings too. An early, fierce champion of art in the workplace, Marron perceived the power of visual experience in reception areas, hallways, and conference rooms to ignite his employees’ imagination, even in the numbers-oriented finance industry. “We all spend probably a third of our lives in our offices,” Marron remarked in 2005. “Therefore, if you can expose us to another aspect of creativity in our time, it’s a good thing, particularly in the securities business.”19 As PaineWebber’s chairman in the 1980s and ’90s, Marron built a widely admired corporate collection—“formidable,” according to New York Times arts reporter Carol Vogel.20 Under his leadership, PaineWebber amassed hundreds (and, later, thousands) of works by the likes of Richter, Lucian Freud, Philip Guston, Jenny Holzer, and Elizabeth Murray, as well as commissioning new art. In an especially notable instance, Susan Rothenberg, in her Sag Harbor studio over the summer of 1988, created a suite of six paintings—twirling figures on wood panels, together seeming to form “a ring of dancers around the room”—for the executive dining space of PaineWebber’s midtown headquarters.21 UBS acquired PaineWebber in 2000, naming Marron chairman of UBS America. Two decades later, the aim of the UBS collection is still to capture the most significant artists of its time; recent site-specific installations include Cerith Wyn Evans’s More Light Research (2019), a monumental suspension of white neon and glass that dominates the entrance lobby of UBS’s offices in London.

Roy Lichtenstein, Post Visual, 1993, oil and Magna on canvas, 96 × 80 inches (243.8 × 203.2 cm), UBS Art Collection. Artwork: © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. Photo: courtesy Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

As the firm’s collection grew, Marron realized that it required serious, dedicated oversight, from the selection of new artwork to the conservation of what had become a major asset. In 1984, he hired MoMA curator Monique Beudert, followed by Armstrong in 1995, who remained an indelible fixture of Marron’s collecting even after they both left UBS, advising Marron in his personal realm until his death. “While the term ‘corporate collection’ often conjures images of sterile offices lined with prints of well-known images, the UBS PaineWebber collection is different largely because Mr. Marron has overseen so many of the acquisitions,” wrote Vogel for the New York Times in 2002, when UBS PaineWebber promised thirty-seven important works to MoMA.22 Discussing the gift, Lowry credited Marron’s boldness: “Don was quite courageous. It’s not the kind of safe collection most corporations build.”23 As of Marron’s death, more than 30,000 artworks resided in over 700 offices worldwide, spanning painting, photography, drawing, and—unlike his personal collection—sculpture and time-based art. To honor the UBS Art Collection’s founder after his death, the bank purchased Choctaw-Cherokee painter and sculptor Jeffrey Gibson’s you have set my soul on fire (2019), a dazzling acrylic-and-glass-bead work that bridges indigenous craft and geometric abstraction.24

Indeed, art and finance have been strange and symbiotic bedfellows for centuries, if not millennia. Marron’s thinking went like this: “Wall Street anticipates the future. Why limit yourself to financial ways of doing it? Good contemporary art reflects the society, and great contemporary art anticipates [it].”25 He also argued that “contemporary art reflects the society that creates it, and Wall Street is certainly a part of that [culture].”26

Don Marron, Kynaston McShine, Marshall S. Cogan, and Richard Oldenburg at the opening of the exhibition Andy Warhol: A Retrospective, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, February 1, 1989. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Star Black

Marron had his own voracious style of looking for new acquisitions. “We never stayed too long on one work and sometimes even our friends who came with us thought it was a little funny how quickly we went through,” William Marron remarked of their time at British and Swiss art fairs, “but the pace never took away our reactions to it.”27 He recalls one of his first studio visits, as an eleven-year-old, with his father to see Ed Ruscha in Los Angeles. His father provided no fanfare or preamble, letting him judge the master’s work on its merit. “I do remember feeling like I saw something special,” he says fondly.28 On a 2015 studio visit, Don Marron and Mark Bradford famously bonded as soon as Bradford’s door swung open: six-foot-six Marron met the notoriously tall artist eye to eye, and both men burst out laughing.29 Despite the pleasure of occasions like this, studio visits offended Marron’s intrinsic sense of fairness, asking the collector or curator, as they do, to appraise a year or two of a person’s life and work in just a few moments. Yet Brice Marden told me, reflecting on his friendship and studio time with Marron, “They know what they’re doing, these collectors. They’re all doing different things. But I liked what he was doing. I always felt very comfortable with him. You didn’t have to worry about what he was going to do with your work. He got a couple of very good pictures and he did good things with them, giving a big six-panel painting of mine to the Modern.”

At the end of his life, Marron leased space in Manhattan’s Fuller Building to showcase his personal trove of modern classics, but included younger names like Jonas Wood and Christian Marclay as well. Marron was busy meeting with museum curators and other collectors there, tireless in his pursuit of art.30 Armstrong tells the story of a Brice Marden show at Gagosian’s Madison Avenue location in the fall of 2019. “There was one work in particular—rich in glowing, glowering garnet red—that was phenomenal,” recounts Armstrong. He immediately called Marron, who left a meeting and came straight to the gallery, buying the work on paper on the spot. Marron passed away while the deal was in process and the artwork arrived shortly after his death. “I unpacked it myself and looked at it alone,” recalls Armstrong. “There it was: a glowing triumph, a tempest of flame and energy, his valediction.”31

1See Evan Beard, “The Four Tribes of Art Collectors,” Artsy, January 22, 2018. Available online at www.artsy.net/article/evan-beard-four-tribes-art-collectors (accessed January 27, 2021).

2Matthew Armstrong, in Anna Dickie, “Conversation|Curator: Matthew Armstrong on Collector Donald B. Marron,” Ocula Magazine, August 14, 2020, available online at https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/matthew-armstrong-on-collector-donald-marron/ (accessed January 27, 2021).

3William Marron, conversation with the author, December 16, 2020.

4Ibid.

5See Michael Shnayerson, “Remembering Donald Marron: The Art Collector in His Own Words,” Artnews, December 30, 2019, available online at www.artnews.com/art-news/news/donald-marron-art-collector-interview-1202673926/ (accessed January 27, 2021).

6Arne Glimcher, “Recollection,” in Don Marron: Chronicle of Collecting (London and New York: Phaidon, forthcoming spring 2021), p. 12.

7William Marron, conversation with the author.

8See William Marron, “Remembrance (II),” in Chronicle of Collecting, p. 107.

9Larry Gagosian, “Remembrance (III),” in ibid., p. 188.

10Donald Marron, in Sharon Zane, “Interview with Donald B. Marron, New York City, 13 September 1994,” The Museum of Modern Art Oral History Program 1–2, available online at https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/learn/archives/marron_final_access_web.pdf (accessed January 31, 2021).

11Ibid., p. 1.

12Donald Marron, quoted in Shnayerson, “Remembering Donald Marron.”

13Donald Marron, in Zane, “Interview with Donald B. Marron,”p. 2.

14Ibid., p. 5.

15Glenn D. Lowry, “Remembrance (I),” in Chronicle of Collecting, p. 21.

16Bill Acquavella, “Remembrance (IV),” in ibid., p. 189.

17Donald Marron, in Zane, “Interview with Donald B. Marron,” p. 17.

18Ibid., p. 23.

19Donald Marron, quoted in Jane L. Levere, “Openers: Suits; Art and Mammon,” New York Times, January 30, 2005.

20Carol Vogel, “The Modern Gets a Trove from Corporate Collection,” April 11, 2002, available online at https://www.nytimes.com/2002/04/11/arts/the-modern-gets-a-trove-from-corporate-collection.html (accessed January 27, 2021).

21Michael Brenson, “Gallery View; In This Painter’s World, Everything Is Several Things,” New York Times, May 6, 1990.

22Vogel, “The Modern Gets a Trove.”

23Lowry, quoted in ibid.

24See “Celebrating the Life and Legacy of Donald B Marron,” UBS Contemporary Art website, available online at www.ubs.com/global/en/our-firm/art/2020/life-and-legacy.html (accessed January 27, 2021).

25Donald Marron, quoted in Shnayerson, “Remembering Donald Marron.”

26Donald Marron, quoted in Vogel, “The Modern Gets a Trove.”

27William Marron, conversation with the author.

28Ibid.

29See Shnayerson, “Remembering Donald Marron.”

30Ibid.

31Armstrong, in Dickie, “Conversation|Curator: Matthew Armstrong on Collector Donald B. Marron.”

Jacoba Urist is an art journalist living in New York. She has regularly written about art and architecture for The Atlantic, New York Magazine, The New York Times, and Smithsonian Magazine, as well as covered the art market and art news for The Art Newspaper. Urist is a contributing editor for Cultured Magazine, where she profiles contemporary artists.

The Summer 2024 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail of Roy Lichtenstein’s Bauhaus Stairway Mural (1989) on the cover.

Alice Godwin and Alison McDonald explore the history of Roy Lichtenstein’s mural of 1989, contextualizing the work among the artist’s other mural projects and reaching back to its inspiration: the Bauhaus Stairway painting of 1932 by the German artist Oskar Schlemmer.

In celebration of the centenary of Roy Lichtenstein’s birth, Irving Blum and Dorothy Lichtenstein sat down to discuss the artist’s life and legacy, and the exhibition Lichtenstein Remembered curated by Blum at Gagosian, New York.

Gagosian and the Art Students League of New York hosted a conversation on Roy Lichtenstein with Daniel Belasco, executive director of the Al Held Foundation, and Scott Rothkopf, senior deputy director and chief curator of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Organized in celebration of the centenary of the artist’s birth and moderated by Alison McDonald, chief creative officer at Gagosian, the discussion highlights multiple perspectives on Lichtenstein’s decades-long career, during which he helped originate the Pop art movement. The talk coincides with Lichtenstein Remembered, curated by Irving Blum and on view at Gagosian, New York, through October 21.

Actor and art collector Steve Martin reflects on the friendship and professional partnership between Roy Lichtenstein and art dealer Irving Blum.

Gillian Pistell writes on the loaded symbol of the American flag in the work of postwar and contemporary artists.

On the occasion of an exhibition at Gagosian, New York, Max Dax met with Andreas Gursky to speak with the photographer about his new work. Here, they discuss the consequences of the pandemic on certain works, the roles of techno music and art history in Gursky’s art process, and the necessary balance of beauty and honesty in the contemporary.

The Summer 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, with two different covers—featuring Takashi Murakami’s 108 Bonnō MURAKAMI.FLOWERS (2022) and Andreas Gursky’s V & R II (2022).

By exploring the conventions of past portraits of industrial designers and architects, Maria Morris Hambourg unpacks Andreas Gursky’s ingenious recent portrait of Apple designer Jony Ive to reveal its layered meanings.

Hans Ulrich Obrist traces the history behind Richter’s Cage paintings and speaks with the artist about their creation.

The Spring 2021 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Gerhard Richter’s Helen (1963) on its cover.

Richard Calvocoressi reflects on the monochrome world of Gerhard Richter’s early photo paintings.