Gillian Pistell joined Gagosian in May 2017 as a researcher and writer. She received her doctorate in art history from the Graduate Center, CUNY, in February 2019. Prior to Gagosian, she worked as a research assistant in the Modern and Contemporary Art Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and has contributed to several scholarly publications, including Pen to Paper: Artists’ Handwritten Letters from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

In November of 2020, Ed Ruscha premiered a group of new paintings at Gagosian, New York, including a trio of canvases featuring the American flag. Hung together in a corner of the pristine, white-painted gallery, the paintings were as confounding for their eccentricities as they were recognizable for their patriotic iconography. Viewers could not help but associate the works with the turbulent climate that had surrounded their creation: a global pandemic, boiling racial politics, a polarizing presidential election (in which voting had ended only days before the show opened).

Ruscha’s diverse renderings of the flag urged viewers to interpret the paintings’ meanings in drastically different ways. RIPPLING FLAG pictures an elongated flag that billows across the canvas, its red and white bars extending beyond the right edge as if it were unending. Top of Flag exchanges the uncanny sensibility of RIPPLING FLAG for concealment: this painting shows only the single, topmost red stripe, a sliver of the white stripe below it, and one row of stars emerging from a glowing halo, while the rest of the banner lurks below the canvas’s bottom edge. The last of the three paintings, an untitled work, undertakes a remarkable act of treason: the flag is rent in two. Its top section, so indicated by its starred blue canton, waves in the painting’s lower register while its bottom few stripes fill the upper. A subtle yet distinct seam floats between the two sections, as if the painting were rolling film strips.

Perhaps greatest among Ruscha’s myriad talents is his ability to bluntly picture American culture and values. His representations of gas stations have immortalized the banality of everyday American life, while his depictions of the Hollywood Sign and the 20th Century Fox logo represent the lucrative film industry that projects American culture worldwide. Ruscha’s images of the American flag can likewise be understood as metaphorical portrayals of the country. These three paintings from 2020 show literal division and lack of visibility and representation, but also, perhaps, a glimpse of optimism as the country moves into the future.

The Continental Congress established the official flag of the United States on June 14, 1777, but its origins are murky; the best-known, though unconfirmed, story is that Founding Father and New Jersey Congressman Francis Hopkinson designed the first flag and that the Philadelphia upholsterer Betsy Ross sewed it. Between that initial declaration and 1960, Congress passed numerous acts to adjust the shape, design, and arrangement of the flag, and to approve the addition of stars as new states were admitted to the union. The flag therefore functions as a living document that records the nation’s past and is adaptable for its future. A potent symbol of nationalism, it spurs troops into battle, inspires songs, and often appears in art as a symbol of the country—its people, culture, and politics.

Early representations of the flag sought to incite nationalist sentiments and to solidify a land of immigrants as American citizens. Emanuel Leutze’s well-known Washington Crossing the Delaware, of 1851, a monumental history painting that Leutze created while living in Germany, pictures Christmas night of 1776, when George Washington led the Continental Army in a surprise attack on Hessian soldiers encamped in Trenton.1 Today, Washington Crossing the Delaware holds a place of honor on the walls of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Measuring an overwhelming twelve by twenty-one feet, the painting dominates a gallery devoted to American history, landscape, and national identity from 1850 to 1875. The Civil War, running from 1861 to 1865, monopolized that period—from the tensions that led to the conflict, through the blood-soaked hostilities, to the divisions of Reconstruction and the nation’s citizens’ struggle to rediscover a united identity. Leutze’s painting, and especially the many prints made after it, became symbols used to organize the nation around the flag that waves in the center of the canvas from Washington’s boat.

Depictions of American flags raised for inspiration or in celebration, as in Leutze’s patriotic painting, were intended to signify a unified populace or bring together a divided one, particularly during times of civil unrest and war. Childe Hassam’s Fourth of July, 1916 (The Greatest Display of the American Flag Ever Seen in New York, Climax of the Preparedness Parade in May) (1916), painted as the country readied itself to enter World War I, is a particularly fervent example, recording a Fourth of July parade that culminated a series of “preparedness” events. Hassam’s rendering of this nationalistic celebration shows the city’s buildings nearly lost in a sea of red, white, and blue.

The flag remained a potent symbol of national unity after World War I, but World War II left Americans shell-shocked, whether they had experienced combat firsthand or seen it in newsreels. After the Holocaust, the atom bomb, and all the sacrifices that the war had demanded, many faced struggles in returning to everyday life, or did not see everyday life the same way. Surely in part as a result, in the late 1940s and early ’50s the flag was transformed into an emblem of the country’s social and political complexity—changing the course of American art history in the process.

Jasper Johns’s Flag paintings are perhaps the best-known representations of the American flag in postwar art. Johns created his first Flag in 1954–55, when the Cold War was in full swing. Although Senator Joseph McCarthy’s campaign against domestic Communism had effectively ended with his censure by the US Senate in December 1954, the paranoid atmosphere of that time remained in the forefront of the country’s collective memory. Fear of “un-Americanness” pervaded the cultural apparatus, and the flag was routinely employed as a symbol of national heterogeneity and loyalty. This sentiment endured into 1958, when Alfred H. Barr Jr., the founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, wished to acquire Flag for the museum’s permanent collection after it debuted at Leo Castelli Gallery in the artist’s first solo exhibition. Concerned that the museum’s Acquisitions Committee would not share his enthusiasm for the painting, but rather would see the work as an unpatriotic desecration of a powerful American symbol,2 Barr provided a sterling character reference for the artist and assured the committee that he “had only the warmest feelings towards the flag,” but to no avail.3 Unable to settle on a decision, the Acquisitions Committee passed the ruling on Flag to the Museum’s Board of Trustees, which according to one account felt it was “perhaps too cynical a portrayal of the flag” and vetoed its purchase for the collection.4 Johns himself allowed a practical reason for his image choice, maintaining that “using the design of the American flag took care of a great deal because I didn’t have to design it.”5 Yet the work’s ambiguity lingered and lingers still, and it would be another fifteen years before Flag entered the museum’s collection.6

The public uncertainty about artists’ use of the flag escalated in the 1960s as politics and art merged. In tandem with the Civil Rights Movement, Black artists focusing on racial oppression set out to create art that disrupted not only the conventional forms and materials of artmaking but also the institutional frameworks within which art was made.7 Los Angeles was a hotbed for this work; Senga Nengudi, Noah Purifoy, Betye Saar, Charles White, and others converged in the city, particularly in the Watts neighborhood, and made art that addressed their position as Black artists in a white-dominated art world and as Black citizens in a white-dominated country. With the founding of Black-owned galleries that showed the work of Black artists, such as the Brockman Gallery, the Ankrum Gallery, Gallery 32, and the Gallery, these artists created a vibrant microcosm whose reach expanded across the United States.8

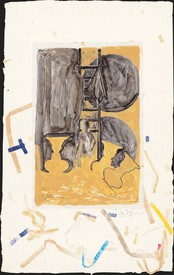

A pivotal member of the group was David Hammons, whose works using the refuse of the Black urban experience, from bottle caps to hair clippings collected from barbershop floors, continue to visualize the Black experience today. Hammons’s Body Prints (1968–79) persist as bold representations of that experience, and many of them feature the American flag—not waving in proud displays of patriotism but appearing instead as backdrops, shrouds, and bindings. Here the flag becomes a device of Black oppression, an emblem not of a people’s liberation but of their enslavement. The medium of these works was largely Hammons’s own body: the artist covered himself, including his hair and clothes, in grease (usually margarine) and lay down on a large support, such as paper or board, leaving an imprint behind him.9 He then sprinkled the grease-laden areas with a powdered pigment, creating a ghostly positive image. As such, the Body Prints fused Hammons’s concurrent interests in graphic art and performance. Indeed, he took on two roles at once when he lay down on his supports: himself and the collective Black-male identity that he is both a part of and embodies. In this way the Body Prints expand beyond the literal one-to-one likenesses of self-portraits to picture Black men more generally.10

In many of the most culturally and politically biting Body Prints, Hammons added the American flag to the image, either using silk-screen or lithography techniques or collaging a real, fabric flag into the picture. Among the most visually, emotionally, and politically powerful of these works is Injustice Case (1970), which refers to the trial of the activist Bobby Seale. Cofounder of the Black Panthers, Seale was charged with incitement to riot and other charges after the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. (The group famously brought to trial on these charges, known as the Chicago Seven, was originally the Chicago Eight and included Seale, before his case was severed from theirs.) During Seale’s trial, the judge ordered that he be gagged and bound to a chair; a drawing of him in this position was widely disseminated in the press. In Injustice Case, Hammons re-presented this drawing, taking the pose of the restrained Seale. He then affixed the print to an American flag, making the Stars and Stripes into a frame for the disturbing scene and in the process transforming it into a symbol of the state apparatus and its systemic racism.11 This use of the flag powerfully undermines its association with the country’s founding principles of “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness,” as outlined in the Declaration of Independence; rather, it is seen as a device for the continued repression of Black America at the hands of the state.

[The Flag] can be a symbol of American strength and unity; a mirror of Cold War anxiety; a representation of racial injustice; an ambiguous icon of terror, oppression, and peace; and an emblem of values-crumbling violence.

As the twentieth century progressed, artists continued to employ the flag in their interrogations and critiques of the country. Cady Noland, for one, repeatedly incorporated the flag in biting installations that confront America’s long-held embrace of violence and encouragement of toxic masculinity. In the american trip of 1988, for example, a draped American flag is riddled with bullet holes.

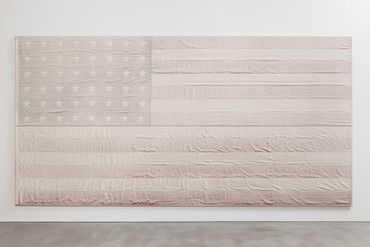

AA Bronson’s White Flag series from 2015 addresses different yet related cultural crises: for these works Bronson coated American flags with a concoction of gesso, ground chalk, and honey, covering the cloth in a ghostly layer of white. According to a press release circulated by the Esther Schipper gallery, Berlin, when it showed a selection from the series in 2015, these works are memorials to 9/11; the white coating signifies the dust that covered downtown Manhattan from the toppled Twin Towers.12 On September 11, 2001, Bronson was stranded at the Toronto airport, unable to board his return flight to New York. He watched on television as the landmark buildings collapsed. When he arrived home seven days later, he was greeted by a city in shock, covered in concrete and debris, but with American flags defiantly displayed amid the destruction.

The whitening of the flag, though, suggests interpretations that push beyond this meaning, and indeed are in line with Bronson’s more activist history. Along with Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal, he was a member of the Canadian artists’ collective General Idea, which pioneered conceptual art and mail art and published the magazine FILE. In the mid-1980s, General Idea became involved with AIDS activism and produced some seventy-five public artworks addressing the crisis—a cause that Bronson continues to champion following Partz’s and Zontal’s deaths from AIDS in 1994. The group’s White AIDS works particularly reverberate with Bronson’s White Flags, in that they likewise obscure their subject beneath a layer of white gesso in an act of mourning and reflection.

Given Bronson’s activism, he was surely aware of the political implications of whitewashing a potent symbol of American nationalism and history. Around the time he created the White Flag works, racial tensions were high in the United States: the previous year, 2014, had seen protests in Ferguson, Missouri, following a white police officer’s fatal shooting of a Black teenager; 2015 witnessed the mass shooting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in which nine Black churchgoers were killed. Although Bronson no longer lives in the United States—he was the director of the artists’-book publisher and store Printed Matter in New York for several years, but now lives in Berlin—he would certainly have been aware of events like these, news of which, shared worldwide, has given the country an international reputation as a high-functioning racist state.

The white coating on Bronson’s flags, however, can also be seen as a call for cross-cultural understanding and acceptance. Within and beyond the United States, Muslims were the targets of violence, both individual and on the scale of war, following the attacks on the Twin Towers. And white is the color Muslims wear while attending Friday prayers or performing rites of pilgrimage; in Islam, it symbolizes peace and purity. Bronson’s covering of the American flag in a color with these meanings in the Islamic religion is unlikely to be chance: he holds a master of divinity degree from the Union Theological Seminary in New York, where he cofounded and was the director of the Institute of Art, Religion, and Social Justice.13 As such, he is surely attuned to the nuanced relationships among the three forces of that institute’s name, and equally surely aware of the symbolic implications of his choice of color. The White Flag works, then, can be understood as a plea for resolution through understanding and communication rather than violence. They evoke contradictory feelings of animosity and optimism, encapsulating in a single artistic concept the full spectrum of the flag’s meaning across cultures. Formally, the White Flag works recall Johns’s White Flag of 1955, which similarly blanches the patriotic image beneath layers of white. The intervening decades between that earlier representation of the flag and Bronson’s, however, lend it yet more possible meanings—evidence that the symbolism of the American flag evolves along with the country it represents.

Sean Scully has likewise engaged the American flag in a series of political works. Born in Ireland but a longtime resident of New York State, the artist holds dual citizenship between the two countries and as such enjoys both an insider’s and an outsider’s view. His art boasts similar characteristics: he understands the givens of his approach but treats them in a highly personal way, so that his grid and stripe paintings are celebrated for their nuanced combination of Minimalism and spirituality. And his focus often transfers to politics, as when he designed posters for the presidential campaigns of both Barack Obama and Joe Biden.14 America’s infatuation with guns, and what Scully calls its “affection for violence,” are perhaps his chief political concerns; his haunting series Ghost from 2016–18—surprisingly for this artist, a group of figurative works—visualizes this brutal American reality.15

The Ghost works all feature a gesturally painted American flag in a range of color combinations, from red and pink-hued white to dark blacks and grays. The stars—symbols of unity—are piled at the bottom of the works; in the canton where they usually are set, they are replaced by a handgun. This series reconceptualizes Scully’s iconic grids and stripes with stark political commentary and a warning on the country’s future. Scully abandons his signature abstract style only for subjects that move him to do so; his other figurative works include the Eleuthera series of 2016, which comprises paintings of his then-six-year-old son. The Ghost works can likewise be understood as inspired by parental love. Scully started painting his gun-usurped American flags after seeing a video of the fatal police shooting of a twelve-year-old boy in Cleveland. Having lost a child himself—his first son, Paul, died in 1983, as a teenager—Scully felt the pain of this child’s death intimately. Furthermore, he fears for his younger son in America’s gun-crazed society, knowing that the worst can happen.16

Scully’s angst focuses not only on his young son’s safety and future in this gun-riddled county; he is also concerned about what this epidemic of violence means for the United States. As he said in an interview for the BBC, “I started to make a series of paintings that I call Ghost, and the reason I call them Ghost is because this little boy is now a ghost, and the principles of America that we talk about in positive terms are also in grave danger of becoming a ghost. . . . Making America, the land of the free, a ghost of what it once promised to be.”17 Scully’s Ghost series speaks to both the gun violence rampant in the country and the crumbling cultural and political values that allow it to continue, a devastating situation that will not change without decisive—and divisive—action.

The meaning of the flag, clearly, has fluctuated through artists’ varying treatments of it over time, laying the groundwork for Ruscha’s use of it in 2020. It can be a symbol of American strength and unity; a mirror of Cold War anxiety; a representation of racial injustice; an ambiguous icon of terror, oppression, and peace; and an emblem of values-crumbling violence. Indeed, representations of the flag in paintings, photographs, and the media are thermometers for the country’s climate. An AP photographer’s image of the Minneapolis unrest following the 2020 murder of George Floyd by a white police officer is a quintessential example: as he runs by a store that is burning to the ground, a protester wields an American flag, which he holds upside down—a potent symbol of a country and its people in distress. The American flag is among the most powerful symbols of the United States; this red-white-and-blue banner encompasses all aspects of the country’s past, present, and future—the good and the bad.

1For a thorough history of Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware see John K. Howat, “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 26, no. 7 (March 1968): pp. 288–99.

2See Lilian Tone, “Chronology,” in Kirk Varnedoe, Jasper Johns: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1996), p. 128, and Lynn Zelevansky, “Dorothy Miller’s ‘Americans,’” in John Elderfield, ed., Studies in Modern Art, vol. 4, The Museum of Modern Art at Mid-Century: At Home and Abroad (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1994), pp. 104 n. 157.

3Johns, quoted in Fred Orton, Figuring Jasper Johns (London: Reaktion Books, 1994), p. 93.

4Orton provides the most detailed account of Johns’s relationship to the American flag, his creation of the first Flag painting, and Alfred H. Barr’s actions regarding Flag. Orton cites Acquisitions Committee meeting minutes and correspondence among Board of Trustees members that recounts their trepidation, such as that of Ralph Colin, who opposed the painting’s acquisition in 1958, and later George Heard Hamilton, who praised its eventual acquisition in 1973 and lamented its denial fifteen years earlier. See ibid., pp. 89–146, 229 n. 19–24, and 236–37 n. 171.

5Johns, quoted in ibid., p. 98.

6In an arrangement worked out with Barr, MoMA trustee Philip Johnson purchased the work from Castelli on the understanding that he would later gift it to the Museum, which he did in 1973.

7See Nizan Shaked, The Synthetic Proposition: Conceptualism and the Political Referent in Contemporary Art, Rethinking Art’s Histories (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017), p. 2. The antiwar, feminist, and gay-liberation movements all also influenced this political turn in art.

8See Laura Hoptman, “An Introduction: David Hammons’s Body Prints,” in David Hammons: Body Prints, 1968–1979 (New York: The Drawing Center, 2021), pp. 8–9.

9See Kellie Jones, South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), pp. 226–27.

10See ibid., p. 226.

11Shaked, The Synthetic Proposition, p. 43.

12Esther Schipper, “White Flag: AA Bronson,” 2015. Available online at https://www.estherschipper.com/exhibitions/71-white-flag-aa-bronson/ (accessed December 6, 2021).

13See AA Bronson, “A Letter to Montreal: Making Love with Jesus,” Journal of Canadian Art History/Annales d’histoire de l’art Canadien 33, no. 2 (2012): 199.

14See Harriet Lloyd-Smith, “Sean Scully on Self-Belief, Election Billboards and the Perils of Rural Germany,” Wallpaper, October 21, 2020. Available online at www.wallpaper.com/art/sean-scully-interview-2020 (accessed September 22, 2021).

15See BBC, “Guns Are Making Ghosts of Our Children,” video interview with Sean Scully, February 1, 2019. Available online at www.bbc.co.uk/ideas/videos/guns-are-making-ghosts-of-our-children/p06zqq28 (accessed September 22, 2021).

16Ibid.

17Scully, in ibid.