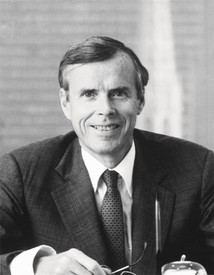

Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

A powerful exhibition devoted to the formative years of four towering figures in postwar German art closed in Hamburg on January 5, 2020, after opening in Stuttgart last spring.1 Among other revelations, Baselitz, Richter, Polke, Kiefer: Die jungen Jahre der alten Meister (The Early Years of the Old Masters) drew attention to Gerhard Richter’s early work at a particularly opportune moment: the year 2018 had seen the release of Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s controversial film Never Look Away (in Germany titled Werk ohne Autor, or Work without author), a fictionalized account of Richter’s life up to the mid-1960s, when he was still signing his work “Gerd Richter.” Although Richter cooperated with Donnersmarck, he later disowned the film.

Donnersmarck had been inspired to make his film after reading investigative reporter Jürgen Schreiber’s book Ein Maler aus Deutschland: Gerhard Richter. Das Drama einer Familie [A painter from Germany: Gerhard Richter. The drama of a family], published in 2005. In a long and engrossing interview with the exhibition’s curator, Götz Adriani, in the Stuttgart/Hamburg catalogue, Richter takes issue with Schreiber’s biographical approach to his paintings of the 1960s, especially those such as Uncle Rudi and Aunt Marianne (both 1965), which were based on black-and-white photographs in the family album that Richter took with him when he emigrated from East Germany in 1961.

There was no strategy behind my choice of photos. . . . On the one hand, I was familiar with the pictures, but on the other hand they could have come from any family album from that time. That’s why I don’t think you necessarily need to know any background information about the people depicted. . . . The penetrating search for knowledge about the content and subjects puts the mystery of the image at risk of getting lost. . . . [Schreiber] believed that pictorial invention could only be explained and interpreted from one vantage point.2

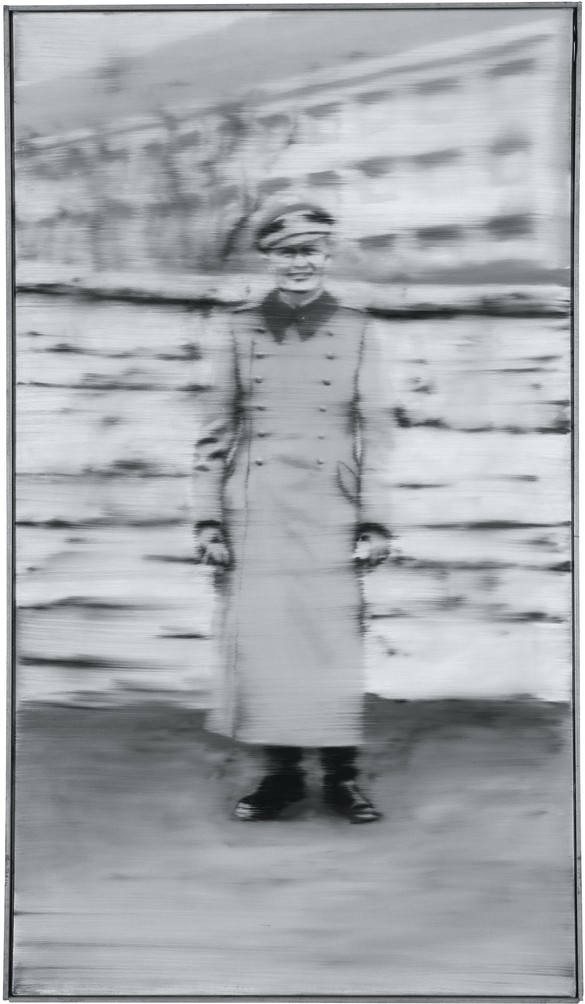

Richter’s uncle Rudi (Rudolf) Schönfelder, his mother’s brother and an attractive figure heroized by the family, is portrayed smiling in full Wehrmacht dress uniform, in front of the outer wall of what looks like a barracks. He was killed on the Western front in 1944, when Richter was twelve. Aunt Marianne, meanwhile, depicts Rudolf’s sister Marianne some ten years earlier, as a young teenager holding her nephew, the four-month-old Gerhard, in her parents’ garden in Dresden. By the end of the decade, diagnosed as a schizophrenic, she would be incarcerated in mental hospitals and forcibly sterilized. In February 1945, as part of a second phase in the Nazis’ euthanasia program and in order to free up hospital beds for wounded German soldiers in rural areas that were less likely to be bombed, she was murdered and buried in a mass grave.

In reply to probing from Adriani, Richter maintains that he “never deliberately concealed the contents”:

I just didn’t mention them and never discussed them. There are many “Uncle Rudis” in Germany and the universality of it is what interested me. He symbolically represents the soldiers of the “Third Reich.”3

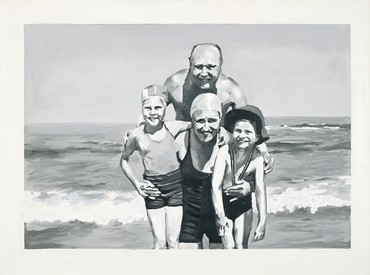

A third picture, Family at the Seaside (1964), was based on a photograph in the album of Richter’s then wife, Marianne (Ema) Eufinger. Considerably enlarged (the painting measures about sixty by seventy-eight inches), it shows the Eufinger family—father, mother, and two children, including the six-year-old Ema—in bathing costumes, grinning at the camera, against a backdrop of the Baltic during a summer holiday in 1938. From this apparently innocent image it would be impossible to infer that Professor Dr. Heinrich Eufinger was a respected gynecologist who had joined the SS in 1935, and from then until the German surrender in 1945 had carried out some nine hundred forced sterilizations of the mentally ill at clinics in Dresden and Leipzig, including the clinic where Richter’s aunt was sterilized. On his fiftieth birthday, in 1944, Heinrich Himmler promoted him to the rank of SS-Obersturmbannführer. After the war, he spent a brief period in Soviet imprisonment, then resumed his medical career in West Germany, retiring in 1965 on a full pension. Although Richter was aware of the fate of his aunt, none of Heinrich Eufinger’s story was known until Schreiber revealed it in 2005.

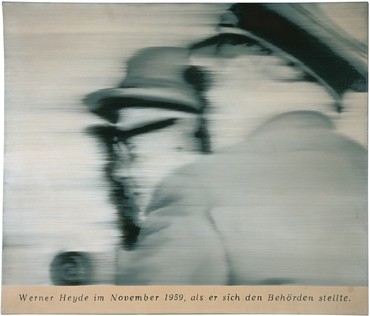

Herr Heyde—another painting of 1965, this time based on a press photo—shows the psychiatrist Dr. Werner Heyde, one of the chief architects of the Nazi euthanasia program, his head in profile and partly concealed by the uniformed upper half of a burly policeman at the moment he surrendered to the authorities in 1959. We know this because at the bottom of the painting Richter has faithfully reproduced the original newspaper caption, using a device favored by American Pop artists but dropping their bright synthetic colors and delight in glossy consumerism and celebrity culture. The drab gray tones and indistinct facial features of Richter’s portrait are more appropriate to his sinister subject. Heyde had evaded justice for over a decade, living and practicing in West Germany under an assumed name. In 1964, five days before his trial on war-crimes charges was due to begin, he committed suicide.

Richter’s reason for working with found imagery such as family snapshots, or photographs in newspapers and magazines, was “to turn something artless into a form of artless art.”4

It became clear to me that, although absurd and epigonic, copying a photo helped me to convey something new. It was of particular importance to me to disassociate myself from art made in the service of leftist politics. . . . it was important that the viewer was not hit with some message or other in my works. . . . For me it wasn’t at all about politics or family but rather about the banality and ambiguity of the source material.5

Like his fellow Saxon Georg Baselitz—who grew up under the same two dictatorships, National Socialism and Communism, and whose father was also a schoolteacher and a member of the Nazi party—Richter admits that he is “extremely allergic to intolerant political, ideological, or artistic statements.”6 What attracted him to the photograph he used for Family at the Seaside was, again, its universal quality:

I was particularly struck by the two arms [of Heinrich Eufinger] that contain, as it were, a family. The protective, beaming father was in fact my father-in-law, but I knew that he was actually an authoritarian whom I really hated at times. He was the typical representative of a generation of fathers that had experienced an authoritarian upbringing themselves and built their careers in the “Third Reich.” I was fascinated nonetheless by fathers who radiated strength, success, and prestige unlike my stepfather.7

Uncle Rudi, Aunt Marianne, and Herr Heyde are classic examples of Richter’s technique of blurring the image by means of dragging a dry brush over the wet paint. The effect is to flatten surfaces, soften outlines, and dilute shadows.

When you paint a photograph, it looks terrible at first. But when I went over it with a wide brush I was amazed at how good the whole thing suddenly seemed. . . .When the effects of blurring make superfluous details disappear, the subject seems clearer but at the same time more mysterious. In cases where I didn’t use my special “sfumato technique,” I just left the pretty thickly applied paint alone.8

With its pronounced chiaroscuro and modeled forms, Family by the Seaside falls into the latter category, in which the paint was left alone. The result is closer to painterly painting, but its monochrome palette makes clear its derivation from a holiday snap.

For Richter, “The blurring . . . is an opportunity to express the fleetingness of our ability to perceive.”9 Fleetingness, ambiguity, mystery: Richter’s preoccupations convey a profound skepticism about the camera’s claims of verisimilitude. Art historian Cindy Polemis has recently commented on this paradox:

In this age of instant digital reproducibility, [Richter’s] works interrogate how images that seemingly portray truths—real stuff—can be wholly untrustworthy and unstable, giving painting a powerful role in the twenty-first century as a medium for confronting the images of our time.10

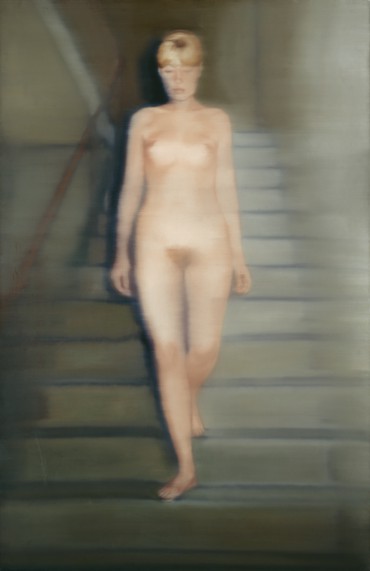

When Richter finally came to paint his wife, he selected a pose that echoed Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) of 1912. Ema (Nude on a Staircase) (1966) is a life-size, full-length portrait based on a staged photograph of Ema that Richter took in the stairwell of his Düsseldorf studio. “It bugged me,” he tells Adriani, “that [Duchamp had] declared painting to be superfluous and drawn a line under it.”11 The tall, enigmatic figure in Ema (Nude on a Staircase), with its “perfect” female body, raises interesting questions about Richter’s attitude toward beauty. As Adriani tells Richter, “You courageously resurrected forms of beauty that had long been dismissed as banal by a modern age to which Baudelaire had added ugliness.”12 Compared to the very different route taken by other postwar German artists, notably Baselitz’s conscious identification with a Gothic tradition of Hässlichkeit (ugliness), Richter’s reply is surprising:

Looking back, I’m sometimes amazed at the certainty that underpinned my idea of beauty. Beauty might well seem old-school and passé to someone focused on the postmodern. My preoccupation with Titian’s Annunciation, with Vermeer and Caspar David Friedrich, is also related to a concept of beauty that art history teaches us. My initial problems with it soon vanished, especially when I realized what a wonderful aspect it is that, in many regards, has unfortunately faded from view and is lost to us now.13

Just as Baselitz has regularly put obstacles in the way of his own smooth progress, however, Richter’s next step was prompted by “the feeling that I was becoming far too settled and everything was turning into a routine.”14 In October 1966 he exhibited his first Color Charts at a gallery in Munich—large-scale reproductions of paint-factory sample cards. These works, which Adriani calls “the negation of painting,” signified the artist’s first mature experiments with abstract painting, albeit based on found source material.15 For the next half century he would alternate between “photo paintings” and “abstracts” (to use the terminology on his website), in ever more compelling variations of subject matter, form, texture, and color.

1See Götz Adriani, Baselitz, Richter, Polke, Kiefer: The Early Years of the Old Masters, exh. cat. for Staatsgalerie Stuttgart and Deichtorhallen Hamburg (Dresden: Sandstein Verlag, 2019).

2Richter, in ibid., p. 128.

3Ibid., p. 130.

4Ibid., p. 100.

5Ibid.

6Ibid., p. 93.

7Ibid., p. 128.

8Ibid., p. 104.

9Ibid., p. 106.

10Cindy Polemis, “Gerhard Richter: Seeing and looking away,” Standpoint, September/October 2019, p. 56.

11Richter, in Adriani, Baselitz, Richter, Polke, Kiefer, p. 146, n. 1.

12Adriani, in ibid., p. 147.

13Richter, in ibid.

14Ibid., p. 148.

15Adriani, in ibid., p. 147.

Artwork © Gerhard Richter 2020 (0024)