Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Fall 2021

The Fall 2021 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Damien Hirst’s Reclining Woman (2011) on its cover.

Fall 2021 Issue

Thomas Houseago and Amélie Simier, director of the Musée Rodin, Paris, talk with Gagosian director Richard Calvocoressi about contemporary sculpture and its foundation in the radical forms of Auguste Rodin.

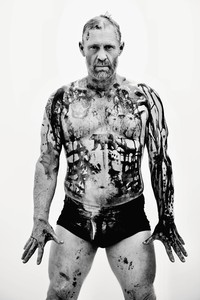

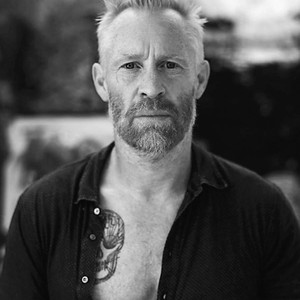

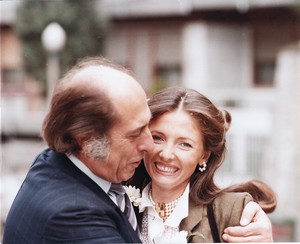

Thomas Houseago, 2021. Photo: Amanda Demme

Thomas Houseago, 2021. Photo: Amanda Demme

Richard CalvocoressiI’d like to begin by looking at the form of the walking or striding man in European art. Thomas, could you speak a bit about this subject in your work? And then Amélie, maybe you could link it to the work of Rodin.

Thomas HouseagoI made my very first walking man in Amsterdam as a student. I read Gravity and Grace [1947] by Simone Weil, which is about spiritual and political gravity and grace, and it made an impact on my thinking. There’d also been a sculpture exhibition curated by Jon Thompson at the Hayward Gallery in London [in 1993] about gravity and grace that stuck in my mind—a sculpture should have both these elements, right? In addition to weight, it has to have a lightness.

I created Walking Man [1995] the summer before I left Amsterdam, and in a way, making the work led me back to Rodin, an artist I hadn’t really thought about for a while but one who understood gravity and grace deeply. Reexamining his work led me back to the idea of energy and the importance of movement in sculpture, these very fundamental ideas of sculpture that I’d shied away from in school. Walking Man bridged my student thinking into my next stage.

Sculpture, when it’s at its best, when I’m at my most at ease with it, feels like it stretches back in time. It’s prehistoric, almost. You see the walking figure in ancient Greek sculpture and you see it in Egyptian art. The stepping pose symbolizes something between, a bridge. Rodin’s love of ancient and diverse sources was another thing that astounded me about him—you could say he was the original modernist, in that he was opening up what it meant to be an artist, drawing from different cultures, different perspectives on how the figure, for example, is depicted.

Most sculpture doesn’t necessarily feel of this time. I think it’s because it’s such a difficult art to do—it takes a toll on your personal life, space, economics, everything. It’s a very brutal commitment. You’re forced to look back and marvel at what was done and realize that in some ways you can’t get better than the Venus of Willendorf. You can’t get better than Egyptian temple sculpture. It’s as good as it gets, and I don’t want to destroy that, I want to highlight it. I don’t think Rodin was saying, Hey, I’m this modern figure who’s destroying the past; I think he constantly tried to reference the past. I had no idea he collected so deeply until I went to the Musée Rodin, in the Hôtel Biron in Paris, where his work, including a headless striding man, is exhibited among his collection of antiques.

RCWhat do you think it is about his headless, and in this case armless, figures that’s so powerful, so expressive?

THI think what he was saying is, The body itself is a presence. He was really talking about somatic experience—the sense that to feel things you don’t need the brain, the head, the personality. You don’t need to create portraiture to gain insight into the human condition. The body itself is this thing we all share. We all share the experience of its vulnerabilities and its strengths, and we live in it for a while and then we leave it. That’s not really about the head. He was a master at that: removing what he felt was unnecessary to the experience.

RCHe’s also, in a way, referring to the fact that so much of classical antiquity has come down to us in fragmentary form, with arms broken off, heads broken off, other limbs broken off. Yet they still have this expressive power—the power of the fragment, I suppose.

Amélie SimierRodin himself would say that he would look for “the inner truth,” and that somehow the fragment leads you to it—it concentrates the way you look at it more clearly. It certainly helped concentrate Rodin’s own way of looking at things. The late Rodin regularly worked with those fragments; he started enlarging them, radically rethinking them.

Auguste Rodin, L’homme qui marche, conceived 1907, cast 1913 by Fonderie Alexis Rudier, bronze, 84 × 28 ¼ × 61 ⅝ inches (213.5 × 71.7 × 156.5 cm). Photo: Musée Rodin, Paris

RCThe energy that we find both in Rodin’s L’homme qui marche [1907] and in Thomas’s Walking Man seems to come from an earlier prototype: the Winged Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre, from the second century BC, one of the most famous sculptures in the world, a great masterpiece of Hellenistic sculpture, which again has no head. That work seems to embody a feeling of onward, forward movement. It has a dynamism that’s exceptional in the sculpture from that early period.

THYeah, this is my own fantasy: to keep going. What I perceive as successful sculptures are objects, they’re not actually living, but they manifest another energy. People talk about sculpture in three dimensions, but I think there’s a fourth dimension, 4-D. I believe sculpture has a unique relationship to death. It’s used a lot in funerary traditions—it always has been. Rodin’s Gates of Hell [1880] is about this space between life and death. The energy you feel in, say, the Winged Victory is like this massive signal of hope, of lightness, a celebration of that which is beyond our bodies.

There is in Rodin this very pagan concern for the life-death continuum: clay as a manifestation of life and death. You constantly see in his figures the living and the dead, like they’re almost falling apart, and zombielike. Some of his figures come from the depths of hell. They come from the earth, and he called a lot of sculptures La terre. It was a way of reminding us about the complexity of being in a body, being alive, and about an energy that’s in our hearts, in our souls, and how that links to our body mass, to having fingers, to having eyes, to having mouths.

Thomas Houseago’s Gold Walking Man (2021) in progress © Thomas Houseago

RCI’m curious about material. A lot of your sculptures are made in plaster, and this again makes an interesting link with Rodin. At Tate Modern in London now there’s an exhibition of Rodin’s plasters. Amélie, can you say a little about that exhibition, and about the status of plaster in the sculptural tradition: What role does it play? Has it changed over the years?

ASThat show started from a visit to the lesser-known Musée Rodin in Meudon, the suburban annex of the Paris Musée Rodin. This was Rodin’s former home and studio; it is now a studio museum with a remarkable collection of his plaster sculptures. Our storage rooms are there, too—it’s the place where we keep, for example, all the original molds taken by Rodin and his assistants from the original plasters, the same molds from which we still cast original bronzes. Rodin had a very intimate relationship with plaster. His use of plaster casts was at the center of his process: he cast works from clay, modified them, assembled them, resized them, repeated them, reproduced them, enlarged them—a whole set of practices that are very modern, very radical to my mind, and that he developed his whole life long.

Rodin’s experimentation with white plaster was first publicly displayed in 1900, in a show he self-curated at the Pavillon de l’Alma in Paris, at the time of the Exposition Universelle. He later reconstructed the Alma pavilion in Meudon, as a sort of memory of this iconic show, and this is what the curators at Tate Modern decided to show. They were interested in exhibiting this very experimental, almost contemporary way of working, showing the materiality of the works and the absence of limits on Rodin’s imagination—his playing with clay and plaster, found objects, recycled materials, sketches and fragments.

Eugène Druet, Rodin au milieu de ses oeuvres dans le Pavillon de l’Alma à Meudon (Rodin among his works at the Pavillon de l’Alma in Meudon), c. 1902, gelatin silver print, 10 ⅛ × 9 ⅝ inches (25.6 × 25.2 cm). Photo: courtesy Musée Rodin, Paris

RCIt’s a way of working rather like assemblage or collage on a very large scale, using different materials and objects. Did Rodin also color his plasters, as Henry Moore often did?

ASHe didn’t color plaster but he did try his hand at colored sculpture, working with other artists and craftspeople—ceramists, bronze casters, glass casters . . . there are wonderful efforts in glass by Jean Cros giving color to masks, like the fabulous mask of the dancer and actress Hanako.

RCThomas, hasn’t this reevaluation of plaster as a material in its own right, rather than as a preparatory stage in the casting of a bronze, really only happened in the last few years? I can’t imagine a show of only Rodin’s plasters taking place twenty years ago.

THThat’s an interesting point. In my mind, the plaster would be the most important part of it. Personally, I started with plaster because I wanted to get out of the found-object discourse that was so prevalent when I was at art school—then, that was the thing to do, and I wanted to escape from it. It didn’t reflect anything I felt inside; I felt at odds with that mechanical kind of Pop world. I also used plaster because it was cheap—a cheap way to escape. The very early works I made in Amsterdam, which I consider my first artworks, were painted really bright. Once I did that first walking figure, leaving it raw, I saw how plaster reacts to light, and that really blew my mind. I suddenly saw that a sculpture has an inside and an outside. It has a made, finished quality, but it also has a relationship to the very act of making. Once I saw that, that was it. I saw the link between drawing, which I love—I draw all the time—and plaster. In some of my early works I would draw on boards, pour plaster on the boards, lift it, and I didn’t realize this would happen but it would print the drawings on the back of the plaster.

I see Rodin’s studios as sanctuaries of process, and I think he knew that plaster could do that and that it was a very accessible feeling. Bronze always carries with it the sense of the monument, money, casting, you know, the whole shebang. Plaster is immediate.

Collection of casts donated by Auguste Rodin to the French state in 1916, Meudon, France. Photo: courtesy Musée Rodin, Paris

RCI think this whole reevaluation of plaster is quite fascinating and relatively recent. When Moore, for example, was trying to find a home for his large collection of plasters, the preparatory plasters for his bronzes, he couldn’t find anyone in the United Kingdom who was interested. Thankfully the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto offered him this amazing space where he could go and arrange them as he wished under natural light.

THIt’s one of the greatest installations of sculpture I think I’ve ever seen, those plasters in Toronto. It’s mind-boggling, the sort of things going on in them that you don’t think of Moore doing.

RCThis September in London there’s a joint exhibition of Houseago’s work and Rodin’s. Can you give a little background as to how this came about?

ASCertainly. We like to offer people new ways of viewing Rodin. Recently we had an Anselm Kiefer/Rodin exhibition, for example. We like to associate or confront Rodin’s works with the work of his own contemporaries, his own collection, and with the work of contemporary artists. It’s important for us, as Rodin’s heirs, to be able to keep his work living with new ways of looking at it. So I’m looking forward to seeing the dialogue with Thomas’s work, because as we all know, when we put two works that come from two different places together, they show us intimate truths.

RCThomas, have you any idea what you’ll be showing in this exhibition?

THFor me, you know, it was scary at first because I’d stopped sculpting for a bit—I was in a hard time in my life, a breakdown in fact, and I thought I’d never go back to sculpture. It scared me too much, it was overwhelming. I was painting exclusively, and it was really the concept of the show that got me back to sculpture—I didn’t want to say no. I felt like Rodin was, from the grave, kind of saying, Come on, dude, sculpt. How could I say no to an artist I adore passionately?

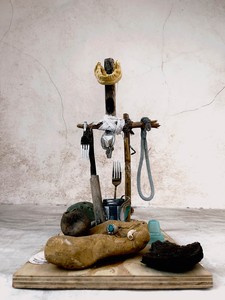

So I’m nervous, you know. I’m nervous about exactly what you’re saying, Amélie, about what happens when objects are put together. Something does happen that’s mysterious. What I’m really excited about is showing one of the last sculptures I made before I went into treatment, which is a walking figure. It’s one I couldn’t solve. It doesn’t have a head. It was unsettling for me at the time. And then returning from treatment I realized it was finished and it was a gem. So that’s in, and then there are really new things. I go to the beach with my kids in the morning, we pick up trash, rocks, and shells—I started making new sculptures with those materials, and I realized they were in some ways influenced by Rodin’s ancient bowls and vases, where he would add his own sculpture to these found vessels.

Thomas Houseago, Ocean Demon Portrait, 2021, mixed media, 20 ¾ × 12 ⅜ × 18 ½ inches (52.7 × 31.4 × 47 cm) © Thomas Houseago. Photo: Amanda Demme

RCWill visitors be allowed or even encouraged to pick up and feel and touch these things?

THOne hundred percent. With my work, that’s always the deal.

RCAfter the period we’ve just lived through, where we’ve all been pretty well forbidden from physical contact with one another, I think the sense of touch needs to be reawakened in everybody. And maybe sculpture can perform a valuable function in that respect.

THThat’s a beautiful point, and I think there’s always a temptation to shy away from it, but in Rodin there’s sex, there’s love, there’s touch, there’s sensuality, right? There’s a celebration of bodies throughout. The Kiss [1882]—think about it, it’s a sculpture almost reproducing, right?

ASI so agree with you, Richard. We have many photos of Rodin cradling in his hands a small object that he had collected, picked up, or put together himself. And as you know, the hand is so present in his work: those numerous cast hands, photos of hands, hands enlarged or drawn. And tactility is definitely one of the great pleasures of sculpture. We curators, you and I, we know we’re so spoiled because we can touch sculpture. Part of the great pleasure of collecting sculpture is to be able to caress it, touch it, hold it in the hand. The tactility of bronze is very singular, as are the unique sensations of clay or plaster. They’re certainly among the great pleasures of life.

Houseago | Rodin, Gagosian, Davies Street, London, September 9–December 18, 2021

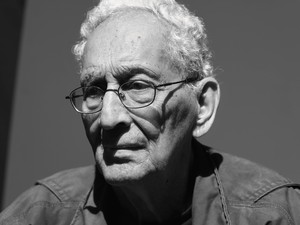

Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

Thomas Houseago was born in 1972 in Leeds, England. He studied at Jacob Kramer College, Leeds, from 1990 to 1991, received a BA in 1994 from Saint Martin’s School of Art, London, and studied at De Ateliers, Amsterdam, from 1994 to 1996. He lives and works in Los Angeles. Photo: Amanda Demme

Amélie Simier holds a diploma from the École du Louvre and the École Nationale du Patrimoine. As an art historian, she’s been working on modern sculpture and sculptors for the last two decades, as well as on the artist’s studio. She has recently been appointed director of the Musée Rodin in Paris.

The Fall 2021 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Damien Hirst’s Reclining Woman (2011) on its cover.

With preparations for Houseago’s Los Angeles exhibition in progress, Deborah McLeod brings us a glimpse inside the artist’s studio.

Art for a Safe and Healthy California is a benefit exhibition and auction jointly presented by Jane Fonda, Gagosian, and Christie’s to support the Campaign for a Safe and Healthy California. Here, Fonda speaks with Gagosian Quarterly’s Gillian Jakab about bridging culture and activism, the stakes and goals of the campaign, and the artworks featured in the exhibition.

Sébastien Delot is director of conservation and collections at the Musée national Picasso–Paris and the organizer of the first retrospective to focus on Anselm Kiefer’s use of photography, which was held at Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain et d’art brut (Musée LaM) in Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France. He recently sat down with Gagosian director of photography Joshua Chuang to discuss the exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Punctum at Gagosian, New York. Their conversation touched on Kiefer’s exploration of photography’s materials, processes, and expressive potentials, and on the alchemy of his art.

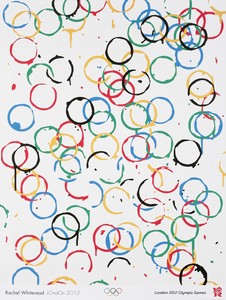

The Olympic and Paralympic Games arrive in Paris on July 26. Ahead of this momentous occasion, Yasmin Meichtry, associate director at the Olympic Foundation for Culture and Heritage, Lausanne, Switzerland, meets with Gagosian senior director Serena Cattaneo Adorno to discuss the Olympic Games’ long engagement with artists and culture, including the Olympic Museum, commissions, and the collaborative two-part exhibition, The Art of the Olympics, being staged this summer at Gagosian, Paris.

On the occasion of Art Basel 2024, creative agency Villa Nomad joins forces with Ghetto Gastro, the Bronx-born culinary collective by Jon Gray, Pierre Serrao, and Lester Walker, to stage the interdisciplinary pop-up BRONX BODEGA Basel. The initiative brings together food, art, design, and a series of live events at the Novartis Campus, Basel, during the course of the fair. Here, Jon Gray from Ghetto Gastro and Sarah Quan from Villa Nomad tell the Quarterly’s Wyatt Allgeier about the project.

In 2023, the collector and patron of the arts Gemma De Angelis Testa donated over 100 artworks from her collection to the Ca’ Pesaro Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna in Venice. On the heels of that exhibition, she met with Gagosian senior director Pepi Marchetti Franchi to discuss the genesis of her collection, the key role of her organization ACACIA (Friends of Italian contemporary art association) in enriching the world of contemporary Italian art, and what it means to share one’s collection with the public.

Nancy J. Troy, Victoria and Roger Sant Professor in Art Emerita at Stanford University, recently published Mondrian’s Dress: Yves Saint Laurent, Piet Mondrian, and Pop Art (MIT Press) with coauthor Ann Marguerite Tartsinis. The book examines the confluence of modern art and fashion, with a particular interest in consumerism, circulation, and the emergence of Pop art. The Quarterly’s Derek Blasberg met with Troy to discuss.

An interview with Marcantonio Brandolini d’Adda, artist, designer, and CEO and art director of the Venice-based glassware company Laguna~B.

In celebration of the life and work of Frank Stella, the Quarterly shares the artist’s last interview from our Summer 2024 issue. Stella spoke with art historian Megan Kincaid about friendship, formalism, and physicality.

Multi-instrumentalist, singer, songwriter, and composer Lucinda Chua meets with writer Dhruva Balram to reflect on the response to her debut album YIAN (2023).

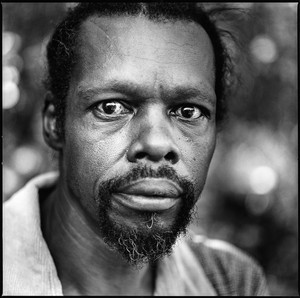

Lonnie Holley’s self-taught musical and artistic practice utilizes a strategy of salvage to recontextualize his past lives. His new album, Oh Me Oh My, is the latest rearticulation of this biography.