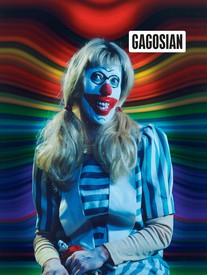

Natasha Stagg’s books Surveys and Sleeveless: Fashion, Media, Image, New York 2011–2019 were published by Semiotext(e). Her writing also appears in the books You Had to Be There: Rape Jokes, by Vanessa Place, Intersubjectivity, Volume 2, edited by Lou Cantor and Katherine Rochester, Excellences & Perfections, by Amalia Ulman, and The Present in Drag, edited by DIS, among others. Photo: Roeg Cohen

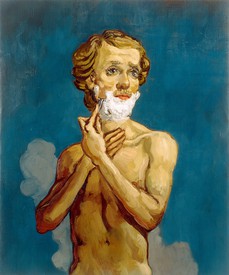

“When I try to make up a face, Rachel ends up in it. It starts to become Rachel,” says the artist John Currin in his Gramercy studio, staring at one of his own unfinished works. Currin’s wife, the artist Rachel Feinstein, has never minded this, he insists. In fact, he continually checks in with her to see if she has changed her mind, depending on what type of body her face ends up on. He is quick to point out, though, that these aren’t portraits. None of his paintings are, really. “I’ve never considered myself a portraitist in the sense that I don’t capture a person’s pain, or her memories, or her aspiration,” he says. “It’s never entered into my work, that anything is being shown about the actual person who sat there. When I make Rachel, she’s both the default ideal and also the most specific thing I could possibly do. So it seems right as the anchor to a kind of obscenity. It’s jarring to me, and I find that interesting.”

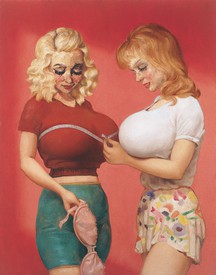

Currin started working on this new series of paintings, the first he has shown in New York since 2010, in January of 2020. In some ways they represent a departure and in others a return to form. The realistic renditions of what he calls “monoliths” are almost colorless, drained of the glowing flesh tones that bring his best-known paintings to life. Stone figures are set in niches, effecting trompe l’oeil versions of bas-relief carvings. “The irony is that they’re pictures of Rachel and big breasts. My same shtick,” he laughs.

“There’s been this thing going on between the face and the body.” Currin is pointing to one figure’s stoic gaze and then her nippleless, water-balloon-like breasts, which hover impossibly over a birdlike body, which in turn is piled atop a similarly shaped nude that appears to be bent in half. Each figure’s face is recognizably Feinstein’s. When Currin started painting “the enormous breasts, the looming breasts,” as he says, over twenty years ago, he negotiated their cartoonish quality by going the opposite route with faces. Painted with a palette knife from the neck up, figures in The Magnificent Bosom and The Bra Shop (both 1997) hold two erotic ideals in one hand: that of the inflated sex doll and that of the tortured painter’s muse, or, more simply, the unnatural and the natural. “When I put Rachel’s face on these,” he says, “it’s a little bit like that, like opening a yawning gap between the two realities of the body and the mind or the face.” Also, “When you paint someone’s face, you are both knowing it intimately and turning it into something that you can never know.”

For a long time, critics didn’t know what to do with Currin’s work, which baldly referenced 1980s catalogue poses and Mad-magazine illustrations, but also the brushwork and subject matter of the old masters. His sensitivity to the similarities between so-called low and high styles often found a middle ground in a recognizable emotion, the real feelings, say, that a catalogue model might not intend to express but are there all the same as she smiles, looks straight ahead, and appears slightly pained or oblivious. One type of feminist critique questioned the motivation behind creating such characters. If these paintings could talk, would they pass the Bechdel test? Of course not, but that’s because, as Currin reminds me, none of the people are real. “Their actions are not their own. They’re mine.”

He goes on, “These are all dolls being played with. Everything you’re doing is a big lie. This whole thing is not really happening. It’s like that argument about when you look at Olympia, she’s looking right at you, messing up the male gaze. I’m not saying [Édouard Manet] didn’t intend to defeat the male gaze as he understood it, but if he did, he’s doing that because he likes to defeat the male gaze. He’s not doing it because it’s a good thing for society. He likes to do it, just like other people like to dunk a basketball. They’re not doing that to defeat people who side with the hoop.” He laughs again. “Sorry, that’s a stupid metaphor.”

For a long time, Currin underlined this idea of “dolls” or otherwise agencyless characters by only using faces he found in playbooks and magazines. “They were sort of a contemporary version of having a Boucher face, where it’s always the same, a face that you don’t have a connection to.” Painting the face of his wife of twenty-four years comes more naturally, though, it being the face he sees most often, but also, “That’s my wife and so it makes me feel more what I’m doing. Whatever misogyny or humiliation or sexism or negative things are in these images, it’s more interesting that I’m doing it to her, to somebody I love.”

In one painting, a pointed foot transcends the niche’s frame, a move typical of the type of display depicted, as well as of comic book frames. It’s meant to further the illusion of dimensionality but also, Currin suggests, to act as an olive branch from artist to viewer. “When you look at Van Eyck’s statues, they’ll have a little bit come over the frame and cast a shadow. It’s these delightful little illusions that matter.” These “acts of generosity,” he says, are especially important when a painting is this “cold,” which isn’t how it started out, by the way. He’s pulling out an earlier canvas to explain how he got here: similarly pornographic poses in color felt too overt, but in alabaster they’re less assuming. Stone is appropriate for public viewing, he adds, since it is the historical medium of public art. Plus, “your physicality is not invoked. It’s not made out of flesh.”

These are the considerations of an artist at work, which are necessarily affected by time and context, and the statues’ white eyes and frozen poses do capture something like the general mood of 2020. First, it was the “mounting horror” of the pandemic and subsequent quarantine mandates. Then, coming back to Manhattan after a summer of familial isolation, Currin was confronted by another type of existential dread, brought on by a boarded-up New York. “This insane shutdown of the whole world,” he says, pouring me coffee from a thermos on one of the first chilly days of October, “pushed me toward the idea of these being melancholy. Closed. There’s no color. There’s all this really explicit nudity but it’s defeated, in a kind of comedic way.”

Each of the images I’m looking at shows a configuration of women whose thighs taper into tiny, splayed feet in pumps that have no beginning or end. Vaginas and anuses are dashes and exes, as if in some bachelorette version of pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey. The women appear uncomfortable, bloated even, as they attempt a sexy display, fingers on privates. The triangular shape of each formation, Currin says, helps the monolith theme along. “They’re pyramidal. It’s like a parody of monumental composition. It’s like what’s-his-name in Close Encounters making mountains out of mashed potatoes.” He laughs, but adds, “They’re not meant to be glib, like, an old master painting of porn—which is the glib description of a lot of my work, I suppose—but it’s the inappropriate solemnity that I’m interested in. And also, I can’t help but mention, because I can’t help but think about all the anger directed at statues in the last six months.”

At fifty-eight, Currin is firmly a part of the canon, taught in schools and shown in major museums. His paintings often make news by selling at auction for millions. Still, in conversation he often reverts to the language of a self-doubting student. “I had some vague idea that over time my work would get sort of classical,” he says, almost wistfully. “But it never did. It still has all the same awkwardness that it had when I was starting out.” When he was starting out, Currin wanted his art to be impenetrable, like that of his Ab-Ex idols of the time. His early works show a frustration with their own genre, smudging color palettes that seem to be taken from other eras, blur-censored versions of other people’s paintings. Eventually, Currin had what he calls a breakthrough when he realized that the doodles he did outside of his studio work could become conceptual studies—paintings of women with anatomically impossible features, commercial poses in classical styles, and other experiments that poked at the implied neutrality of portraiture.

He had his first solo show at White Columns, New York, in 1989. As soon as the 1990s started, Currin’s paintings of women of all ages, made uncanny by cartoon characteristics and childlike expressions, were considered controversial. They were seen by some as mocking, or at least at odds with the more politically minded art of the day. Not only were these paintings explicitly figurative, they did not attempt to neatly parallel art and commerce, like an Andreas Gursky, or skewer identity objectification, like an Adrian Piper. Currin let criticism roll off him, happy he was at least getting noticed. “When you’re young and you’re trying to get attention, it’s good to not imagine in too much detail what the attention’s going to be,” he tells me. “If I think the water’s going to be cold no matter what, it’s a way to not worry about how cold the water’s going to be.”

The accusation of misogyny left the artist an open target for other kinds of ire, and there is much of that to go around in the art world, especially after something sells for seven figures. Reducing Currin’s success in 2004 to a “sodden heap of gimmicks,” a 5,000-word takedown in the New Republic admittedly got the artist’s attention. Elsewhere, his work was repeatedly described as anachronistic or nostalgic, words that sometimes house passive aggression. As a defense mechanism, Currin absorbed the critique, leaning into the expectations that detractors set out for him. “I wanted to do what I’d been accused of doing,” Currin has said of a painting of three women, each with the face of Feinstein (Thanksgiving, 2003). “That’s why I included the old-fashioned mirror and the Corinthian columns.”

The paintings I am looking at could be called pornographic anachronistic nostalgia on paper: women in lingerie are piled onto one another, spread-eagled or smothered by genitalia, affecting Greco-Roman statuary or Chandela-dynasty stone carvings of the positions of the Kama Sutra. But there is a solemnity here that needs to be accounted for. The offenders in these works are more frozen than posed, perhaps stunned by the gaze of a Medusa-eyed critic. They’re “monuments to lust,” Currin says.

One wall of the studio is covered with wigs on mannequin heads, creating a backstage-like setting for sketches of women flashing the viewer or sitting on a face. We’re on the topic of offensiveness again. “Sometimes I wish I was doing different imagery that wasn’t embarrassing,” says Currin, “in the way that it might be embarrassing to whoever-buys-the-painting’s kids’ friends’ nannies. But then again, I’ve gotten used to it. And really, over time, all that stuff is pH neutral after a while. It will look old-timey in another fifty years, if even that.”

When Currin was younger, he says, he liked “the idea of offending people” because at least that meant he was being recognized. “I wanted to become a famous artist. I don’t feel the same way now.” Perhaps, I suggest, that’s because he is a famous artist now. It’s also that he’s older, he answers. “There’s an aspect of flirtation to being offensive. . . . When you’re young and attractive, it’s easier to feel that.” Not that he ever set out to offend, specifically. “If I was honest about what I really wanted, it would be that people would fall in love with me by looking at my paintings. That they were so beautiful people would start crying and fall in love with me, you know? That’s what I want, is to be like Botticelli. I don’t want it to be a succès de scandale.” Later, he clarifies, “People mistake my being offensive for slumming in a lower order of sophistication. I do indulge myself sometimes and enjoy people’s distaste for how easy my work might seem, as a result. If I ever fell prey to being gimmicky, it would be that the form should be as stupid as possible, but you should be able to keep peeling it forever.” Looking around the studio, he says, “I don’t know what a woman would think of these . . . but men might find these as offensive as women might. It’s unsexy to everyone. And yet it’s porn. And then, being sculpture, you know, the form carries the meaning, literally and figuratively. The decisions about form carry sociological meaning. There’s no narrative.”

“No narrative” might be a way to describe many of Currin’s artistic ideas, meaning that the images are rife with stories yet hope not to project any, opting for a pantomime or joke instead. “It was a revelation to me,” he says, “to realize that Poussin is funny. I used to dislike Poussin because of the narrative. I didn’t like that a story was being told by the poses. I don’t want to know whether it’s Udipious and Ferinthius being surprised by Sledonius or something like that; I don’t know the story.” Poussin’s paintings must only depict his own feelings, using mythology as metaphor, says Currin, darting around his studio to find the right book and paging through it. “They’re about him looking around his own world and thinking it was crummy and not classical and disappointing. Everything looked to him like Route 1 in Connecticut, with Arby’s and shit everywhere. I may be imagining, but I get a sense that he’s dissatisfied with the way his world looks. That it doesn’t jibe with the way he thinks things ought to look, and not just aesthetically. He’s embarrassed by his world, maybe in the same way that I feel sort of embarrassed by my world.”

This revelation led to more, says Currin. He kept finding a similar uneasiness, or “just a nagging feeling of inauthenticity—hence all the classical Roman-looking people running around, and then, in the landscape, you see something real happening. It’s all about nostalgia, about pining for some other time and kind of creating it there, Arcadian Earth. That’s part of all painting, rather than just my situation as an American painter.” It’s helped Currin find his place in the art world, or at least in an art history timeline. “I’m sort of born with a clown suit on and I can’t help it,” he says. “As an artist, I’m never going to make something that’s going to be unpolluted. . . . It’ll never be classic. My work is based on the vache period of [René] Magritte, [Francis] Picabia, and [Gustave] Courbet, all that goofball stuff. Then, the older I get, I can start to see little echoes of that in supposedly classic art and I’m starting to realize, yeah, maybe all art’s this way. Maybe that’s part of being a good artist, just living with that feeling.”

Artwork © John Currin; photos: Rob McKeever

John Currin: Memorial, Gagosian, 541 West 24th Street, New York, September 14–October 30, 2021