As a writer, I’ve often been tasked with writing about art. It’s a lovely task, to be sure, and always an interesting challenge—how can I interpret a visual medium through words? How can I conjure the magic of an artwork with an entirely different set of tools?

Opportunities abound for writers to respond to the work of artists—the catalogue essay is a classic example—but I’ve often wished for a reciprocal space where artists might respond to a work of literature. My desire is partly selfish: the great fortune of having your work interpreted by another artist is a way of giving it a second life. But I also think it can be an incredibly valuable exercise for the one doing the interpretation. Like a Rorschach inkblot, another person’s work can serve as a kind of tinder through which your own ideas and viewpoints become manifest. The artist and the writer are both revealed anew through the exchange.

And so we started Picture Books, a new imprint that pairs contemporary fiction writers with contemporary artists. There are no limits or conditions or requirements. The artist is given a text and has total freedom to create an image that is, in whatever way, in conversation with the writer’s work.

I’m so excited for the first book in the series, bringing together the writer Ottessa Moshfegh and the painter Issy Wood. Moshfegh’s work is always fearless, funny, and brilliant. It made perfect sense, then, to pair her with Wood, whose own work is alive with visual contradictions and a spiky intelligence. Both share a gothic humor and an attunement to the darker currents of the world, the hidden realms where shame and desire intersect.

—Emma Cline

ISSY WOODI loved your story so much.

OTTESSA MOSHFEGHI loved your painting.

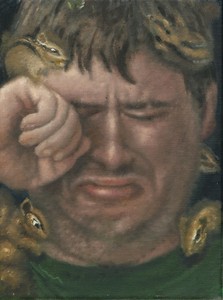

IWWell, then we’re good. I’ve never made a painting in response to a story before. It was completely a new process; I didn’t want to be dismissive of any part of the story that you felt was important, but I developed a preoccupation with the chipmunk and it took over in a powerful way [laughs].

OMI love the chipmunks in the painting. Did you think of it as the same chipmunk repeated or different chipmunks?

IWIn my head it was the same chipmunk. Chipmunks are exotic animals to me because they’re not native to the UK. It was a real Google Images situation. [Your main character] Jerome Littlefield’s involvement with the chipmunk felt like the most directly surreal part of the story; it was the telltale sign that the young woman, Stacy, had lived more than he could dream of.

OMIn your painting generally, how much do you use the Internet to research images?

IWA lot. I’ve gotten rid of all of the hang-ups that older male art-school teachers put on doing so. It’s the best library I could ask for. I particularly like auction websites: all these sales of people who’ve died, or people who’ve gotten divorced and someone needed cash, and these big auction houses log every single object that’s been through there and that have gone under the hammer. I make a lot of work pretty fast and it seems to suit the process. I refuse to beat myself up for using the Internet to work in the oldest medium in the world. I can beat myself up for a bunch of other things, but it won’t be that. How much does the Internet factor into your writing?

OMI definitely use it for research. And I tend to be a really bad researcher. I’ll skim things and not really understand them because I don’t want to know exactly what the truth is. I’m just looking for a direction or my own idea.

IWIf you’re looking for the whole truth, either way, you probably shouldn’t look on the Internet. I find it fun all the same. Right now I’ve been delving through a lot of things that men would like, especially cars. I could spend hours on these forums where men are really horny for their cars, which made me think about what it is to try on a male perspective in writing, which you’ve done in this story. Is that something you’ve done before?

OMMy very first book was a novella that was written in the perspective of a man, a young, very alcoholic man in the mid-nineteenth century. I actually felt really close to him and admired that character, whereas with Jerome, in this new story, he’s like a perversion of a male version of myself. He’s what would happen if I allowed myself to exploit my most pathetic insecurities.

Maybe because of all of the ways I feel tortured with having been born female, when I pick a voice to speak in that’s male, I can ignore the depths of my neuroses and look at them as something to be made fun of.

IWWhether those insecurities are yours or his, they’re always going to seem to me a lot more pathetic coming from a man. The casualness with which Jerome says “Maybe I’ll just write a couple of screenplays,” for instance, is really extraordinary. I’ve heard this casualness from a man recently and meanwhile, I’m thinking about whether having an extra piece of fruit is just too decadent. This idea of talking up one’s own project before getting it off the ground—is that something that happens with you or is that reserved specially for the man?

OMI don’t think it’s just for men; it’s anyone with an inflated sense of self, which a writer usually has. I totally have that hang-up, too. What I think is funny about the male factor of this story is that I wrote it a few months before I met my husband, who is also a writer. And when he read this story, he saw himself in it too and I think maybe thought that I was making fun of him. I was like, Oh, no, no, I wrote that before I met you, and this story is more about me than anyone else I actually know. The maleness of it is like an old cliché, but making fun of female insecurity is too complicated for me. I can’t be as scathing and funny for some reason. My own sexism. Maybe because of all of the ways I feel tortured with having been born female, when I pick a voice to speak in that’s male, I can ignore the depths of my neuroses and look at them as something to be made fun of.

IWYou’d have to be a glutton for punishment to want to see yourself in this story. I was trying to work out where the line between the delicious schadenfreude of watching this man fumble—calling his mom and trying to have her convince him that he’s a genius—ends and where pity begins. Do you pity Jerome? If this man is a part of yourself, do you have any sympathy with that?

OMI have sympathy, but I’m really unkind about it. I’m pretty tough on myself. I’m curious how you feel and how you respond to praise.

IWTerribly. I’m always going and looking for it and shunning it when it appears. It’s still quite new for me. I could absorb praise when it came from a teacher at my school, when I was a kid being praised for something that had very clear, delineated rules—good grammar, good language, good answers to math questions—versus someone praising my paintings, which I don’t know what to do with. I feel like what happens when you’re that hard on yourself is you think everyone who compliments you is a fool. And so not only do you not just sit there and take the compliment, the person who just complimented you has just gone down in your estimation, and then the lonely cycle begins.

OMYeah, I’m glad you said it and I didn’t [laughs]. But that’s exactly how I feel too. There are certain people I see as peers. The people I admire the most are people whose practices are completely mysterious to me and praise from them is usually different because it’s somehow within an appreciation of the subtlety of the work. But yeah, everything else is just kind of bullshit feeling.

In your painting, I assumed that the face was a portrait of Jerome in a way. I’m curious about your experience of imagining his face—did you imagine his physicality? Or just the image.

I was asking myself to paint a portrait of this man without knowledge of his physicality. In the story, you learn what he eats and how he might look while staring at someone’s breasts in a cafe, but I wanted mainly to go for sadness.

IWJust the image. I wanted to find a sad man. I could have gone into the few details you provide in the story and built from there, but I didn’t want to open up that can of worms. I was asking myself to paint a portrait of this man without knowledge of his physicality. In the story, you learn what he eats and how he might look while staring at someone’s breasts in a cafe, but I wanted mainly to go for sadness.

OMI think he’s perfect.

IWI think it would have been a lot easier to make the painting if I’d hated the story, honestly.

OMWhy?

IWIt would be low stakes, but with this, because I like the story, I was trying to work out who I was trying to please aside from myself always. I wanted to do it justice.

OMDo you find that that’s true all the time with your painting, or was there more of that because this was like an assignment?

IWIt was an assignment. It stirred a school feeling in me. And I go around claiming to want some kind of assignment, almost wishing the structures of school could be put back on me, but I’m in completely the wrong job for that. And then when it comes, the need to please is so ingrained that it’s crippling. But not so crippling that I don’t get the job done.

OMPeople come to me with things—Will you write an essay about this or that—and I find that I always fail and back out if it’s something I’m not actually interested in enough to push myself to do it. But the desire to have some kind of pressure or discipline or authority is really present for me too. Not necessarily in a school way, but it’s a lot to have to organize your own ambition and then still do the job of the creator, unbridled and manic and insane. Looking back at Jerome and his therapist, there is that dynamic of the authority I need to please.

IWOutsourcing the authority helps; I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to do something just for myself. Passion to me is a very corny word by itself. And since what I do doesn’t feel like the traditional idea of work, I have to engage in as many trappings of work as I possibly can so that, I don’t know, some entity will be pleased with how I’m doing.

How was your pandemic?

OMWell, I didn’t get sick. I wrote a novel, and I’d moved into a house three or four months before it started. Before that I was in an apartment—a lot like Jerome Littlefield’s, actually—so it was cool to have a house with more room. It’s been completely crazy overall, though, and when things started to, quote unquote, Open up, I was like, I don’t want to go back.

IWOh yeah.

OM Part of me as a writer is like, Oh, I need to stay and observe society and respond to it, and then the other part of me is like, Fuck other people, right? I just want to be with the land and the birds and the wind and fresh water and die in peace, but [laughs]—

IWYou’re not allowed both. You’re not allowed to observe society close up and also have the land and the birds and the peace. As soon as people enter the equation, you’ve lost your peace.

OMThat’s so true.

IWI was thinking of this painter Lee Lozano, who’s one of my favorites. For a show, she decided to stop communicating with women entirely. This was for a specific project, but it turned out that she really loved not speaking to women so she never spoke to a woman again. I think she wrote a whole book explaining her motives, but I don’t really want to know any more. I just like the idea of something befalling you and then finding out that it suits you, and I wonder whether you feel like you’ve been in training for a pandemic with certain levels of solitude for a while, or whether it was as much of a shock as it was to most other people?

OMI think it was still a shock. Maybe because I’m really good at being alone and at home, it wasn’t as hard for me. I rarely go anywhere anyway. I missed my family, weirdly; family became very important. I say “weirdly” because I’m not the kind of person to miss people. I miss dogs but not people. How about you? Were you in London the whole time?

IWYes. Just before the pandemic, I was starting to think about how much time I was beginning to spend alone and whether that was good for me and whether I’m more of a people person than I give myself credit for. A lot of my worst demons thrive in solitude, as much as I wish that wasn’t true. But all I wanted to do was live alone and work alone and not have to deal with people, and the pandemic just tripled it. I think the parts of me that were relieved by the pandemic, the solitude, were very unhealthy parts of me. I made a lot of work, but I took several steps back in recovery in all forms. And bouncing back is obviously a lot harder to do than to slip into it in the first place. But I have a lot of good work to show for it. I don’t know, it’s a double-edged sword. And, like you, as soon as things were open again, I’d pretend that I was still scared of covid, there were still cases floating around, but it wasn’t covid at all. It was just the idea of having to be presentable, or having to be on form, or—

OMI really don’t want to have to go back to the way things were. I’m hoping that all this experience of the pandemic will actually make us wiser in some way. We started out talking about the Internet, and I want to get off the Internet in the same way I want to leave society, but I’m not off the Internet, you know [laughs]? I could be. I just am not.

IWHave you ever tried making visual art?

OMYeah.

IWHow did it go?

OMI was always studying art while I was in school, and out of school too. I really liked taking painting classes and life drawing. I wished that I could have been a better photographer. I’m a really bad painter.

IWSome people like that. People try actively to become bad painters now, so.

OMMaybe it’s my moment. Actually, I took this test once online that was supposed to tell you how sophisticated your color palette is visually, like what colors you can recognize. And it turns out I’m really stupid when it comes to colors.

IWReally? A color moron.

OMYeah. Apparently other people experience color more subtly than I do—I can’t even imagine what that must look like. That’s what this test told me, that I’m just unimaginably stupid about color. Apparently things are way more complicated than I perceive them.

IW[Laughs] That’s a nice thing to be told by an online test: things are far more complicated than you think. I like being told that with some authority from an algorithm, that’s amazing.

So what’s your next novel about?

OMWell, the next book that comes out, it comes out in the spring and it’s called Lapvona, which is the name of a fictional village from the late Middle Ages, and it’s the story of the stuff that happens in this village over a year and a half. And the novel I need to get back to work on, which is hopefully the next one I’ll finish, is narrated by a ghost on the occasion of her resuming consciousness, and she recounts her life and death. She was born in Shanghai and ended up emigrating to San Francisco in drag, assuming her brother’s identity. That’s as far as I’ve gotten. I’ve just been stuck on a ship.

IWI know, it’s hard to proceed from being stuck on a ship in drag. I don’t know.

OMIt is.

IWI mean, that’s limbo if ever I’ve heard of it.

OMYeah.

IW I’m going to order them when they’re—

OM Oh no, I’ll send them to you.

IWI’d like that. Maybe it can get me back into reading, rather than just scanning essays about suicide in Harper’s.