Donald Judd: Untitled: 1970

In this video, Flavin Judd, the artist’s son and artistic director of Judd Foundation, discusses a historic large-scale work by his father from 1970, ahead of its presentation at Art Basel Unlimited 2024.

Fall 2022 Issue

In this second installment of a two-part essay, Julian Rose continues his exploration of Donald Judd’s engagement with architecture. Here, he examines the artist’s proposals for projects in Bregenz, Austria, and in Basel, arguing that Judd’s approach to shaping space provides a model for contemporary architectural production.

Donald Judd with Jeff Kopie, Architecture Office, Marfa, Texas, 1993. Photo: © Laura Wilson

Donald Judd with Jeff Kopie, Architecture Office, Marfa, Texas, 1993. Photo: © Laura Wilson

When Peter Zumthor wrote to Donald Judd in February 1990 to ask the artist’s opinion on his design for the Kunsthaus Bregenz, he explained that he had initiated the transatlantic dialogue in part because “there are few competent partners of discussion for this task to be found around here. . . . I’m not too excited about most of the new museums which have been built in Europe recently.”1 Zumthor saw Judd, in other words, not only as an artist and architect he admired but as something of an authority on the art museum as well. This sentiment was echoed in the official invitation that Judd received from the Kunsthaus’s founding director, Edelbert Köb, that December: “I have been following your thoughts on art, art management and especially museum buildings which you have expressed in articles and interviews. They have made an impression on me and are compatible with my own views. I would therefore like to obtain your collaboration on a new museum project.”2

What had Judd said to make such a powerful impression? Never one to mince words, he had relentlessly repeated several scathing critiques of art museums since the early 1970s. The fundamental problem, he argued, was that the primary purpose of these buildings was no longer to exhibit art. Instead, their role was symbolic and economic, as engines to drive tourism and urban growth: “A museum of contemporary art . . . has become a necessary symbol of the city and of the culture of the city all over the world.” The result was an “expensive efflorescence” of new institutions in which, ironically, “art is only an excuse for the building housing it.”3 Two corollaries followed. First was “atrocious” architecture.4 In the neoliberal ’80s, the combination of populism, commercialism, and historicism espoused by architectural postmodernism proved a heady cocktail, seamlessly blending pious appeals to the past with unquestioning exuberance over new development, and most of the major museum projects constructed on both sides of the Atlantic adhered to this style.5 Not surprisingly, given the profound lessons about space that he had learned from studying Renaissance buildings, Judd was particularly incensed at these postmodern pastiches: “Recently the symbols of the past are simply pasted on. . . . The new use of Classicism isn’t even three-dimensional, the essence of Classicism. It’s all paper cut-outs.”6 But worst of all, the ascendance of this new style, all surface and symbol, branding and spectacle, had severed all connection between the architecture of these museums and their contents: “They never provide a true sense of what is being done in contemporary art.”7

Donald Judd, Architecture Office, Marfa, Texas, 1993. Photo: © Laura Wilson

It was undoubtedly this last point that was most appealing to Köb, who saw the Kunsthaus as a unique opportunity to reconnect art and architecture within one institution. As he made the case to Judd, “This museum will be the first work of contemporary architecture for modern art built in Austria since the Secession.”8 It was a provocative precedent to invoke: the Vienna Secession had been a cradle of the Gesamtkunstwerk. And it was one that Köb knew more than a little about, having served as the president of the Secession for the nine years preceding his appointment as director of the new Kunsthaus. A practicing artist himself—a prerequisite for the job, given that the Secession had operated as an artists’ association since its founding—Köb had also supervised the first major renovation of the Secession building, the Secessionsgebäude, since World War II, overseeing the restoration of both Joseph Maria Olbrich’s 1898 structure and the full artistic program it houses, including Othmar Schimkowitz’s sculptures in the entry portal and the famous Beethoven Frieze painted within by Gustav Klimt in 1901–02. But Köb’s intimate familiarity with the Secession’s rich history also gave him a clear understanding of its distance from the present. It had, after all, promoted the Jugendstil model of a literal fusion of painting and sculpture with architecture. Its devices were medieval, even antique: the frieze and the pediment, the mosaic and the mural. Above all, the Secession version of the Gesamtkunstwerk had relied on ornament. That expansive and ambiguous category has provided fertile ground for connections between art and architecture in so many different styles and eras, but ornament became strictly verboten as architectural modernism gathered momentum in the early twentieth century, thanks in no small part to the vociferous anti-Secessionism of that other famous Viennese architect, Adolf Loos.

Köb’s essential insight was to see that by the late twentieth century, the connection between art and architecture had become conceptual rather than physical, a matter of shared intellectual interests rather than complementary material praxes, defined above all by the emergence of “real space as a central concern of contemporary art.”9 Judd had unquestionably played a leading role in this shift, famously declaring in 1965 that “real space” had become the arena of the best new visual art.10 And so, with Judd’s help, Köb proposed to take this “common intellectual position” as the “determining influence on the program of the Kunsthaus.”11

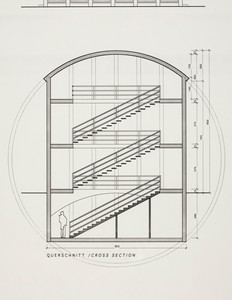

Adrian Jolles, section drawing of Donald Judd’s design for the Kunsthaus Bregenz administration building, 1992, inkjet print on vellum. Adrian Jolles Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas

And yet, ironically, this conceptual affinity set up physical confrontation. How would art and architecture learn to coexist within the “real space” to which they both laid claim? A striking ambiguity in Köb’s initial invitation to Judd reflected this difficulty. While he could clearly articulate what he wished to avoid, telling the artist that he hoped for “an alternative to the usual large sculptures (such as [Alexander] Calder’s very popular works) which stand in front of museum buildings as advertising symbols,” Köb’s description of what he actually envisioned was so vague as to be almost meaningless: “I have in mind an architectural sculpture/structure/space segmentation.”12 In the end it was a purely pragmatic consideration that clarified matters. When Köb first contacted Judd, the plan was for Zumthor’s new building to contain only exhibition space while the museum’s offices would be housed in a repurposed residential building nearby, but in early 1991 the local building department declared the old house unfit for renovation because of structural damage. When he heard the news, Judd immediately offered to design a new office building. Carried away by his enthusiasm, Köb accepted the offer on the spot, before discussing it with Zumthor. He felt that the symbolic power of two great buildings—one by an artist and one by an architect—perfectly captured the interdisciplinary ambitions of his institution and outweighed any concerns about the unity of the museum complex. Zumthor was thus presented with the idea of a Judd building as a fait accompli, and it was this unpleasant shock that had provoked his furious letter to Köb in October 1991.13 It was only with difficulty that the latter managed to convince him to at least await the results of Judd’s design.

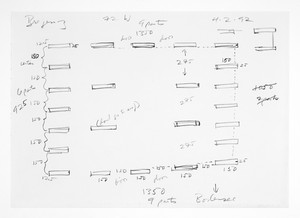

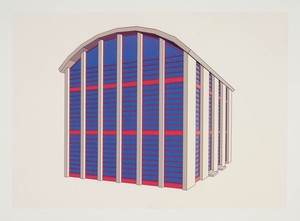

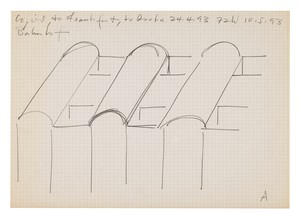

Meanwhile, Judd got to work. An annotation on his earliest surviving sketch for Bregenz reads “rounded like artillery sheds.”14 And indeed he approached the project as a fresh version of the problem that had preoccupied him while he was renovating those two buildings in Marfa, Texas, to house his 100 untitled works in mill aluminum: what combination of proportions and geometry will merge a vaulted roof and a rectilinear volume into a harmonious whole? Initially trying a 1:1 correspondence between the height of the main building and the vault above—the same ratio he had used for the Artillery Sheds in Marfa—Judd eventually decided that a multistory building would be necessary to house all the required functions. His solution was to conceive of the building as a four-story rectangle (three above grade plus a basement) precisely circumscribed by the circle that set the curve of its vaulted roof. In the final CAD set, this circle is drawn into the cross-sections as a continuation of the double line of the roof; this explicit articulation of a regulating geometric schema lends the drawings an unmistakably Vitruvian flavor.15 A similar classicism is clearly legible in the plans, where Judd experimented with a series of planning grids that are almost Palladian in their simple modularity.

Rudolf Wittkower, “Schematized plans of eleven of Palladio’s Villas,” illustration in his Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism (1949; New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988). Used with permission of John Wiley & Sons; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

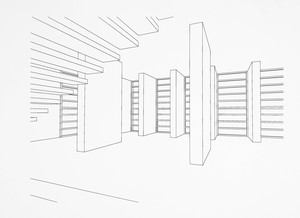

Indeed, Judd’s single-mindedness recalls Rudolf Wittkower’s characterization of the Venetian master, which Judd would have read in his classes with the eminent scholar: “What was in Palladio’s mind when he experimented over and over again with the same elements? Once he had found the basic geometric pattern for the problem ‘villa,’ he adapted it as clearly and simply as possible to the special requirements of each commission . . . reconcil[ing] the task at hand with the ‘certain truth’ of mathematics.”16 Replace “villa” with “vaulted shed” and this could be a verbatim description of the design process Judd applied in both Marfa and Bregenz.17 His main innovation in the latter was to propose piers, rather than columns, for the building’s structural system. By making each pier extend the full width of one segment of the planning grid (1.5 meters, or just short of five feet), he created a system of implied equivalences whereby the same module could be expressed as both solid and void. As renderings suggest, this was an intriguing architectural extension of one of the paradigmatic ideas that Judd had explored in his stacks and progressions.

Nevertheless, Zumthor was unimpressed, and he rejected Judd’s design out of hand. He was particularly vocal about his dislike for the overt anachronism of the vaulted roof, but he cannot have had much enthusiasm for the striated façade, either. Köb wrote that Judd’s building, “like his sculptures, is defined with the greatest clarity in terms of construction, proportion, and material.”18 That was true; as in many of his artworks, Judd had produced a kind of diagram of conceptual synthesis, a whole in which visibly opposed elements—solid and void, structure and space, concrete and glass—were unified by being subsumed within the same overarching systems of geometry and proportion. Zumthor, too, believed in wholes; he ultimately justified his rejection of Judd’s design by arguing that it would undermine his stated goal of achieving “architectural unity” on the museum site.19 But his notion of unity was far more synthetic, even atmospheric. His own design for the museum wove together a concrete core, a steel superstructure, and a skin of etched glass panels to create an enigmatic, translucent prism that rose like a gestalt from the edge of the city.

Donald Judd, drawing for the Kunsthaus Bregenz administration building, February 4, 1992, pencil on paper, 8 × 11 inches (20.3 × 27.9 cm). Donald Judd Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas

Adrian Jolles, rendering of the interior of Donald Judd’s design for the Kunsthaus Bregenz administration building, c. 1992, inkjet print on paper, 11 ¾ × 16 ½ inches (29.8 × 41.9 cm). Donald Judd Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas

As the architect officially commissioned by the state, Zumthor had ultimate authority over all aspects of the Kunsthaus project. His rejection of Judd’s design was therefore final, and Zumthor himself proceeded to design the administration building that currently stands on the site. (The building’s program was also expanded to include a bookstore and café on the ground level.) Yet Köb remained convinced of the importance of a Judd building for establishing the identity of his institution, and he eventually convinced the mayor and the city planning council to give him a new site in a lakefront park, a five-minute walk from the Kunsthaus.20 Now that Zumthor himself was designing the museum offices, however, Köb needed to invent a new use for the building as well. His solution was that it become a research and documentation center called the Kunst-Architekture Arkive. The new plan was fully in place by the fall of 1993, and it seems that it was only Judd’s untimely death early the following year that prevented the eventual realization of his design. But by this time a funny thing had happened: Köb had completely changed both the site and the function of Judd’s building, yet its actual design had not changed a bit. Presumably this did not bother Köb because he saw its primary purpose as essentially representational: in his words, a building by such a well-known artist would have “great symbolic and prestige value,” perfectly signifying the broader ambitions of the Kunsthaus.21 Yet context and function are ostensibly two of architecture’s determining influences, and this Judd-authored object—mobile, less spatial than symbolic, its form independent of function—was behaving as something much more like a large sculpture than an actual building. Ironically, Köb’s very insistence on his interdisciplinary program had pushed Judd’s design back toward the status of the autonomous work of art.

Did the relationship between art and architecture fare any better inside Zumthor’s crystalline volume? After all, Köb was not the only one who believed that the new Kunsthaus should foster new kinds of interconnection between these fields. As Zumthor described his project, “It is no white cube, no abstract white shell. Its material presence was important to us: exposed concrete, polished concrete, and steel and glass of various qualities. We thought that works of art would profit from this explicit materiality, deliberately presented with understated, industrial clarity. We wished to have a physical, sensual framework for art.”22 It is certainly true that Zumthor’s spaces have abandoned any pretense to neutrality, and it is likewise true that the artworks exhibited within them tend to profit from his approach. Indeed, the most striking thing about Zumthor’s space is perhaps not how consistently good art looks within it, but how consistent the art looks—period.

Adrian Jolles, rendering of the exterior of Donald Judd’s design for the Kunsthaus Bregenz administration building, c. 1992, inkjet print on paper, 8 ¼ × 11 ½ inches (21 × 29.2 cm). Adrian Jolles Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas

View of the Kunsthaus Bregenz (1997), designed by Peter Zumthor, Bregenz, Austria. Photo: Werner Dieterich/Alamy Stock Photo

The Kunsthaus’s programming evinces the wide variety that might be expected from a top-tier institution with a well-established presence in the international art scene, exhibiting a representative cross-section of the vast range of heterogeneous cultural practices that fit under the capacious rubrics of modern and contemporary art. The building, meanwhile, is justly renowned for its daylighting system, which combines a sophisticated multilayered skin with an ingenious structural system to create enormous lightboxes between each floor, each one drawing sunlight in laterally and diffusing it downward into the gallery below. The effect is to suffuse the spaces with a perfectly even luminescence, creating a harmonious experience of vivid perception and heightened spatial awareness, at once tactile, kinesthetic, and affective. This light falls with equal power on artworks of vastly different character, indeed on art that would seem to invite vastly different interpretive modes, or even posit entirely distinct modes of experience: from the lush colors of Abstract Expressionist paintings through the deadpan archival documentation of ’70s Conceptual and performance practices to the assemblages or dispersed artifacts of recent installation art. When Zumthor’s project won the EU Mies Award for 1998, the jury praised him for “creating an introverted place of contemplation.”23 And indeed he has, in an almost Kantian sense: it’s a space for moving slowly, breathing deeply, looking carefully, and speaking in hushed tones, if at all. But it produces this contemplative mode even for some artworks that are not really asking for contemplation, and for others that might not seem worthy of it if encountered in any other context.

If there is no hint of neutrality here, nor is there any competition, any of the sense of architecture trying to upstage art that has drawn criticism in other museums by other celebrated designers. There is, rather, a palpable sense of augmentation, of enhancement. Given the impeccable installation shots these spaces produce, and the fact that the global circulation of such images is what keeps the art world turning—constituting not just the primary mode of reception of most artworks today but their primary mode of existence—it might be tempting to think about Zumthor’s building as a kind of architectural version of the Facetune app. But to characterize their effects as purely visual would be to overlook the extraordinary physicality of these spaces, immediately apparent to any visitor. What Zumthor has produced, ultimately, is the museum as prosthetic, a physical and optical framework that binds the two categories of thing within it—bodies of visitors and works of art—into a mutually supportive embrace.

Installation view, Donald Judd: Farbe/Colorist, Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria, May 13–June 6, 2000. Artwork © 2022 Judd Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Markus Tretter © Kunsthaus Bregenz

Needless to say, this was not the relationship that Judd’s works were asking for. When a Judd exhibition was eventually held at the Kunsthaus, in 2000, the objects looked flat, almost pictorial, clearly missing the dynamic friction—the striking combinations of light and shadow, the obstreperous materiality, the emphatically visible structure—provided by spaces like the Artillery Sheds. In Bregenz, then, neither Judd’s building nor his artworks found the kind of dialectical exchange to which he had aspired in Marfa, and by 1993, perhaps he himself would have seen that coming. When the buzz generated by his involvement in the project garnered him an invitation to speak at a symposium on museum design held that year, “The Museum of Contemporary Art: Towards the Next Century,” Judd refused—and, as if in a reminder to himself, he scrawled across the program, “Stupid. Don’t do it.”24 If he was serious about expanding his practice into architecture, he would have to escape the museum’s orbit.

Incredibly, Judd did get a final opportunity to do just that. In July 1992, a few months after Zumthor had rejected his design for the administration building, he received a letter from Thomas Kellein, then director of the Kunsthalle Basel, inviting him to collaborate on an architectural project. “The building, however, is not a museum,” Kellein told Judd, almost sheepishly—but presumably by this time Judd welcomed that news.25 And it was an enormous opportunity. Hans Zwimpfer, a prominent architect and developer in Basel, was working on a massive urban infill project that would cover an existing rail depot with a new six-story office building, called the Peter Merian Haus. At over 325 meters (355 yards) long, it would be the largest single building in the city. In part because of its huge size and staggering cost—it had required raising half a billion Swiss francs in investment capital—Zwimpfer was sensitive about public perception of the project, and, with consummate Swiss efficiency, he had formed an art-and-architecture working group, led by Kellein, to study “the best possible form of collaboration between artists and architects” with the ultimate goal of boosting the project’s prestige and cultural relevance.26

Donald Judd, 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, 1982–86 (detail), installation view, North Artillery Shed, The Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas. Artwork © 2022 Judd Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Douglas Tuck, courtesy The Chinati Foundation

Even with the best of intentions, there was ambiguity from the start. Kellein told Judd “the idea is to invite you to design the whole facade as if it were a sculpture.”27 But did that mean that Judd was invited to treat the building as a sculpture, manipulating both surface and volume as he wished? Or was the implication that a Judd façade would make the whole building into a sculpture, no matter what form it was wrapped around? Judd clearly thought the former. Criticizing the look of the “thin, pasted-on facade” of Zwimpfer’s initial design, he proposed a new massing in which he felt surface and volume were linked more deeply.28 It was based, he explained, on a “form [I] developed in architecture in renovating the artillery sheds in Texas.”29 The reply was courteous but firm: “The sketched vaulted roofs are less appropriate for this project, especially because of their height and the difficulties they create. . . . In any case the building cannot be enlarged.”30 It turned out, in fact, that nothing about the building’s form could be changed at all: its length and height as well as the number of stories and their assigned functions had all been predetermined by economic factors. In the city, space was a commodity, and it would be shaped not according to an artist’s desires but rather, as Zwimpfer had insisted from the beginning of the project, “according to market development.”31 As long as he left the volume unchanged, Judd was told, he was welcome to explore variations in the color and material of the building’s surface. Judd may have devoted his career to working in what he called real space, but in the actual zone where architecture collided with the inexorable realities of urban development, he found himself squeezed into the fractional thickness of a sheet of glass.

Judd was not known for his willingness to compromise, and the fact that he continued to work on the Peter Marian Haus after his vaulted-roof scheme was rejected is a testament to the depth of his desire to be involved in a real architectural project. Perhaps he even saw that the same high economic stakes that limited his role in the design almost guaranteed that the building would be realized, and decided that the trade-off was worth it. In the fall of 1993, Judd delivered a design in which subtle variations of color and finish in the building’s glass envelope signaled the different functions housed in the spaces within, attempting to link the building’s surface to its volume after all. Around the same time, he hung large-scale prints of the construction drawings for Peter Marian Haus on the walls of his architecture office. Prepared by Zwimpfer’s office, these documents conveyed an unmistakable air of real-world architectural production—comprising dense palimpsests of interlayered structural information and technical annotation that were in utter contrast to the ingenious simplicity of Judd’s own pencil sketches. Indeed, by hanging them even after learning that the overall design could not be altered, it was almost as if Judd was celebrating the reality of the project and affirming the pride he felt in his contribution.

Photograph of a model for the Peter Merian Haus, Basel, sent to Judd in 1993. Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas

Donald Judd, drawing for the Peter Merian Haus, 1993, pencil on paper, 8 × 11 inches (20.3 × 27.9 cm). Donald Judd Papers, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas

Judd’s instincts were correct; the Peter Marian Haus was too big to fail. While the artist’s death, in February 1994, had forced Köb to abandon all hopes of constructing the Arkive building in Bregenz, in Basel Zwimpfer forged ahead, realizing a façade with a pattern of variations based on Judd’s drawings. Yet while Zwimpfer was adamant about Judd’s authorship, making it the cornerstone of his branding of the project, this attribution seems questionable at best.32 In his last letter to Judd, from late December 1993, Zwimpfer had begun by wishing Judd a quick recovery before explaining that his office was engaging in a technical study of the façade, and that soon “we will therefore again have a lot of formal questions.”33 Sadly, these questions would never be answered; Judd’s health deteriorated rapidly and he passed away less than eight weeks after Zwimpfer sent this letter. Given Judd’s meticulous attention to detail, his hands-on approach, and especially the sketchy quality of the documentation he produced, it seems a stretch to characterize anything realized posthumously from his drawings—indeed anything he did not approve in person—as his “work.” But ironically, as in Bregenz, the tremendous symbolic and prestige value of Judd’s authorship ultimately outweighed concerns with the actual particulars of his design.

And so, whether by institutional politics or urban economics, Judd found himself repeatedly frustrated in his attempts to realize his own buildings and was never able fully to take his place among the architects he admired. But this distance from the profession also made room for new approaches. Above all, it allowed Judd to see that it was possible to shape space without creating new form. At least since the beginnings of modernism, architects themselves had forgotten this, preoccupied as they were with the tabula rasa condition assumed to be a precondition for innovation by most avant-garde practitioners. Ironically, too, in their pursuit of novel forms, architects largely ceded the actual production of space to forces outside of their discipline; to industry, to planning, to the market. For every iconic building designed by a celebrated architect—say, a new art museum—there are thousands of structures instantiated by these other forces. Judd’s transformational insight was to recognize that in these overlooked remainders there might be plenty of space for both life and art; all that was required was a little elbow grease and imagination.

Architecture Office, Judd Foundation, Marfa, Texas, 2018. Photo: Matthew Millman © Judd Foundation

There was an ethics in this approach, too. In 1992, somewhat ruefully describing his experience at a recent architecture conference, Judd recalled, “They . . . quoted Gottfried Semper, saying the first act of architecture is to break the ground. I think the first act of architecture would be to do nothing whatsoever. . . . The major aspect of this century, of the present, is an incredible destruction of the land.”34 Indeed, whenever he could, Judd tried to restore not only a structure itself but the environment surrounding it; at the Artillery Sheds, for example, he had worked with a soil-conservation consultant to reseed the area with native trees and grasses, seeking to mitigate some of the ecological damage that had accrued over decades of military-industrial use. This was a radical approach for 1981, and as the field of architecture has slowly shifted, with “adaptive reuse” gaining currency as a legitimate form of architectural production, and increasing attention paid to everything from embodied energy and construction waste to building emissions and environmental performance, Judd seems like not just a precedent but a model. If his objects unquestionably changed the trajectory of visual art in the twentieth century, from our contemporary perspective some of the debates they engendered—sculpture versus theater, Minimalism versus Postminimalism, art versus objecthood—seem to be settling into the esoterica of art history. But the spaces he shaped will continue to speak to us as long as we have museums to build, landscapes to heal, cities to live in.

1 Peter Zumthor, letter to Donald Judd, February 24, 1990. Bregenz Project Files, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas (JFA).

2 Edelbert Köb, letter to Judd, December 22, 1990. Bregenz Project Files, JFA.

3 Judd, “On Installation,” 1982, in Donald Judd Writings, ed. Flavin Judd and Caitlin Murray (New York: Judd Foundation and David Zwirner Books, 2016), pp. 310–11. Originally published in LAICA Journal 32 (Spring 1982), this essay was reprinted later that year in English and German in the catalogue for Documenta 7 and in 1989 in Donald Judd Architektur (Münster: Westfälischer Kunstverein), so would likely have been read by both Zumthor and Köb. It bears emphasizing that while Judd’s argument sounds familiar today, it was remarkably prescient given that he was writing a decade and a half before the so-called “Bilbao effect” had firmly established the idea of the art museum as an engine of economic development.

4 Judd, “Una Stanza per Panza,” in Donald Judd Writings, p. 641.

First published in German over several issues of Kunst International in 1990.

5 To name two high-profile examples, James Stirling’s Neue Staatsgalerie, an explicit pastiche of Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s Altesmuseum, Berlin (completed 1830), had opened in Stuttgart in 1984; and Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery in London, a Prince of Wales–approved mannerist confection, was under construction as Judd was corresponding with Zumthor and Köb (it would open to the public in 1991).

6 Judd, “A Long Discussion Not about Master-Pieces but Why There Are So Few of Them: Part 1,” 1984, in Donald Judd Writings, p. 370. First published in English in Art in America in September 1984, and reprinted in English and German in Donald Judd Architektur.

7 Judd, “Ausstellungsleitungsstreit” (Exhibition direction’s dispute), 1989, in Donald Judd Writings, p. 559. First published in German in Kunstforum, April/May 1989.

8 Köb, letter to Judd, December 22, 1990.

9 Köb, Kunsthaus Bregenz, pamphlet published by the Kunsthaus to promote the new museum buildings in 1993, n.p. Author’s translation.

10 Judd, “Specific Objects,” in Donald Judd Writings, p. 141. First published in Arts Yearbook in 1965, this text had an enormous impact on the discourse around contemporary art in both America and Europe and came to stand as one of the core manifestos of Minimalism, although Judd himself repeatedly protested that he did not consider himself part of that artistic movement.

11 Köb, “Kunsthaus Bregenz,” in August Sarnitz, ed., Museums-Positionen: Bauten Und Projekte in Osterreich/Buildings and Projects in Austria (Salzburg: Residenz Verlag, 1992), p. 127. Text published in English and German.

12 Köb, letter to Judd, December 22, 1990.

13 Köb, correspondence with the author, January 19, 2022. Zumthor’s letter, cited in the first part of this essay (which appeared in the Summer 2022 issue of the Quarterly), was the one in which Zumthor wrote that Judd “should not be working as an architect for an administrative building.” Ironically, when he felt his own architectural authorship threatened, Zumthor expressed a preference for exactly the scenario that Köb had wished to avoid, raising the possibility that Judd could contribute an outdoor artwork to the project. Zumthor, letter to Köb, October 23, 1991. Bregenz Project Files, JFA. Author’s translation.

14 See the drawing dated September 28, 1991, Bregenz Project Files, JFA.

15 These drawings were prepared by Adrian Jolles, a young Swiss architect whom Judd had initially hired to work on the renovation of his country house in Eichholteren, Switzerland.

16 Rudolph Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, 1949 (London: Academy Editions; New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988), p. 68. Judd purchased the 1952 edition of Wittkower’s book as a student in Wittkower’s class at Columbia in the fall semester of 1960; he kept his copy in his library in Marfa, with his final exam from January 30, 1961, tucked inside. He had chosen to write essays on the following prompts, both of which seem relevant to his approach to designing the Bregenz building: “Give an account of the Renaissance approach to proportion with reference to theoretical writings,” and “Discuss the problem of the Renaissance church facade with special reference to Alberti’s and Palladio’s contributions.” For a copy of the exam, see Donald Judd Student Records, Judd Foundation Archives, Marfa, Texas.

17 Judd also experimented with this geometry in a series of ultimately unfinished concrete buildings he envisioned for the Chinati Foundation. See Richard Gachot, “Donald Judd: The Concrete Buildings,” Chinati Foundation Newsletter 21 (2016): pp. 24–92.

18 Köb, in “Donald Judd archiv kunst architektur, Bregenz: Projekt des Kunsthauses Bregenz,” in Jean-Christophe Ammann, Räume für Kunst. Europäische Museumsarchitektur der Gegenwart (Hannover: Kestner-Gesellschaft, 1993), p. 46. Author’s translation.

19 Zumthor, letter to Köb, October 23, 1991.

20 Köb, letter to Judd, July 19, 1993. Bregenz Project Files, JFA.

21 Köb, “Kunsthaus Bregenz,” in Sarnitz, ed., Museums-Positionen, p. 127.

22 Zumthor, “Art Museum of Bregenz,” project description provided for announcement of the EU Mies van der Rohe Award for European Architecture, 1998. Available online at https://www.miesarch.com/work/381 (accessed May 1, 2022).

23 “Edition 1998,” jury citation for 1998 EU Mies van der Rohe Award for European Architecture, March 7, 1999. Available online at https://www.miesarch.com/edition/1998 (accessed May 1, 2022).

24 Draft program for symposium to be held at University GhK Kassel, December 4–5, 1993. Bregenz Project Files, JFA.

25 Thomas Kellein, letter to Judd, July 2, 1992. Basel Project Files, JFA.

26 Kellein, letter to Judd, July 15, 1992. Basel Project Files, JFA.

27 Kellein, letter to Judd, July 2, 1992.

28 Judd, letter to Hans Zwimpfer, May 18, 1993. Basel Project Files, JFA.

29 Judd, letter to Zwimpfer, n.d. (likely June 1993). Basel Project Files, JFA.

30 Zwimpfer, letter to Judd, June 14, 1993. Basel Project Files, JFA.

31 Zwimpfer, “Some Notes on the Project ‘Banhof Ost,’” February 23, 1993. Basel Project Files, JFA.

32 In 2002, Zwimpfer published a book about the building in which Judd is posthumously credited with the façade design: Zwimpfer, Peter Merian Haus Basel: At the Interface Between Art, Technology and Architecture (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2002), p. 92. The book also documents contributions to the project made by other artists, but these were largely introduced after the design was complete and consist primarily of various installations in the building’s atriums.

33 Zwimpfer, letter to Judd, December 22, 1993. Basel Project

Files, JFA.

34 Judd, lecture at the University of Texas at Austin, March 9, 1992. Courtesy University of Texas Libraries at the University of Texas at Austin.

Julian Rose is an architect and critic based in New York City. He is working on a book about museum architecture, Architects on the Art Museum, forthcoming from Princeton Architectural Press in 2024.

In this video, Flavin Judd, the artist’s son and artistic director of Judd Foundation, discusses a historic large-scale work by his father from 1970, ahead of its presentation at Art Basel Unlimited 2024.

The Fall 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Jordan Wolfson’s House with Face (2017) on its cover.

Richard Shiff speaks with Caitlin Murray, director of archives and programs at Judd Foundation, about the archive of Donald Judd, how to approach materials that occupy the gray area between document and art, and some of the considerations unique to stewarding an archive housed within and adjacent to spaces conceived by the artist.

Julian Rose explores the question: what does it mean for an artist to make architecture? Delving into the archives of Donald Judd, he examines three architectural projects by the artist. Here, in the first installment of a two-part essay, he begins with an invitation in Bregenz, Austria, in the early 1990s, before turning to an earlier project, in Marfa, Texas, begun in 1979.

Art historian Eileen Costello and Yale School of Art professor Marta Kuzma discuss Donald Judd’s two-dimensional work and how the lessons he learned from the innovations of Abstract Expressionist and Color Field paintings permeate his entire body of work. Their conversation is moderated by Caitlin Murray, director of archives and programs at Judd Foundation.

Peter Ballantine, Donald Judd’s longtime fabricator of plywood works, and Martha Buskirk, professor of art history and criticism at Montserrat College of Art in Beverly, Massachusetts, discuss the development, production, and history of the largest plywood construction Judd ever made, an untitled work from 1980.

In this video, Flavin Judd, the artist’s son and artistic director of Judd Foundation, leads a walkthrough of the exhibition Donald Judd: Artwork: 1980 at Gagosian, West 21st Street, New York. Flavin connects the work to the concurrent retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the permanent installations in Marfa, Texas, highlighting how it fits within Judd’s oeuvre.

Flavin Judd, the artist’s son and artistic director of Judd Foundation, speaks with Kara Vander Weg about the recent installation of the sculptor’s eighty-foot-long plywood work from 1980 at Gagosian, New York.

David Cronenberg’s film The Shrouds made its debut at the 77th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in France. Film writer Miriam Bale reports on the motifs and questions that make up this latest addition to the auteur’s singular body of work.

Alison McDonald celebrates the life of curator Richard Marshall.

Alice Godwin and Alison McDonald explore the history of Roy Lichtenstein’s mural of 1989, contextualizing the work among the artist’s other mural projects and reaching back to its inspiration: the Bauhaus Stairway painting of 1932 by the German artist Oskar Schlemmer.

The mind behind some of the most legendary pop stars of the 1980s and ’90s, including Grace Jones, Pet Shop Boys, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Yes, and the Buggles, produced one of the music industry’s most unexpected and enjoyable recent memoirs: Trevor Horn: Adventures in Modern Recording. From ABC to ZTT. Young Kim reports on the elements that make the book, and Horn’s life, such a treasure to engage with.