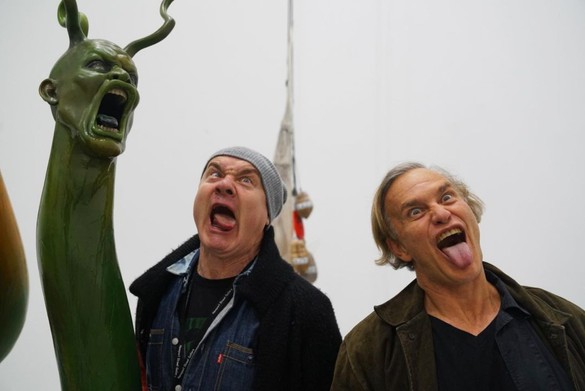

Journalist James Fox is a former feature writer and foreign correspondent for London’s Sunday Times. His writing has appeared in Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone, London Review of Books, and The Observer, among other publications. He is the co-author of Keith Richards’s memoir Life, awarded the 2011 Norman Mailer Prize for Biography.

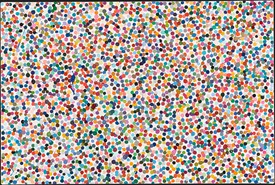

Since emerging onto the international art scene in the late 1980s, Damien Hirst has created installations, sculptures, paintings, and drawings that examine the complex relationships between art and beauty, religion and science, and life and death. His work traces the uncertainties that lie at the heart of human experience. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates

James FoxCan you tell me when and where you first met Ashley?

Damien HirstAshley was among the first people I met in New York. When I did my warehouse show Freeze [in London], in 1988, I met Clarissa Dalrymple, who used to run the Cable Gallery in New York. Cable Gallery was the gallery; their exhibition roster was unbelievable—Ashley, Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, Meyer Vaisman. She said, “Have you ever been to New York?” And I was like, No, I can’t afford it. I was still a student at Goldsmiths. She said, “You’re coming to New York; I’m getting you a ticket and you’re staying in my house.”

The first night I arrived, Clarissa had a party for me, and Ashley was there. Robert Gober was there as well. They were the artists I’d spent the last year and a half reading all about in magazines, so it just blew my mind.

JFWhat blew your mind particularly about Ashley’s work?

DHIt was just fucking unfathomable and totally brand new. I had no clue how to take it on board—I didn’t know which angle to look at it from. I didn’t know whether he was a painter or a sculptor. It was art that existed at the perfect point for me.

When I first went to art school, I was into the 1950s, the 1960s, and some 1970s painters. I thought the world had turned to shit and I needed to put it right. I was into Rothko and a bit of Bacon. But then I realized I was trying to make a comment about the world I was living in but was looking backwards, and it started disturbing me. So I began looking around at what was going on in art magazines. And then there was the New York Art Now show at Saatchi Gallery [in 1987–88, with work by Bickerton, Gober, Koons, Peter Halley, and others], and a light went on for me: “Oh, this is it, this is everything. It’s Minimalism, it’s commercial consumerism, it’s color, it’s painting, it’s sculpture, it’s collage, it’s Kurt Schwitters.” Ashley’s work had it all for me.

JFWhat were Ashley’s works like at the time?

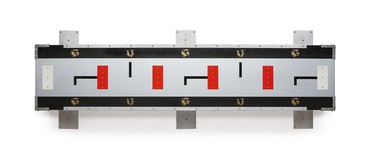

DHThere were the “wall contemplation units,” these things on the wall with writing on them. They were so confident that you couldn’t understand them; they defied interpretation but then sort of revealed something. They were very confrontational artworks. I loved them.

I remember looking at one, Gugug (1986). It had these brackets everywhere, so it was sculptural, kind of like a Donald Judd, and it was more like a record shop sign than a painting. When you looked long and hard enough, you realized he’d painted the letters in a complex, hard-to-read way, so that different combinations would spell gugu, or ugu, or ug, these stupid words you can only read.

The whole thing about painting and art is hidden meaning. In these pieces by Ashley, you go, Oh, there’s the hidden meaning. What does it reveal? Fuck all. And as lost as I was, I uncovered the fucking truth of the thing—but what even was it?

JFIn the past, he’s told me that he thinks you’re the funniest person he’s ever met. He talked about meeting you in New York. He said he couldn’t bear you at first. And then—

DHFunny, honestly, because I thought it was 100 percent mutual love at first sight. I don’t know what it is.

JF[Laughs] Well, pretty quickly, you did become soulmates. When I interviewed him in 2016, he told me, “The reason I was close to the Brits was because they’d made these forays over to New York and they’d stay for a couple of weeks and they were young and on the go. When I first met him, I couldn’t stand him. He was obnoxious. He was the most horrible of all of them. [Laughter] But he grew to be my favorite in pretty short order. We found we had a lot in common. We became thick and fast and he ended up staying with me on several of his trips to New York. We’d go out every night. We were terribly behaved. We’d order burritos for breakfast at 4pm every day, huge, thick American burritos, sitting on the bed like a couple of schoolboys mumbling.”1

DH[Laughs] Yeah. He was really generous. I mean, he was way ahead of me—I had devoured all the Neo-Geo interviews he’d done before I went to New York, and I thought, I don’t know how I’ll be able to do an interview because these artists are just so clever when they’re answering questions.

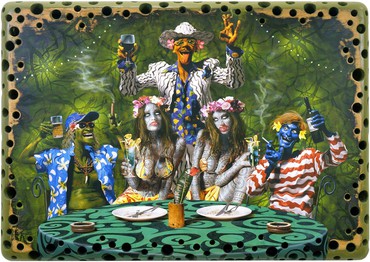

JFAshley often speaks, as you do, about the arcane vocabulary of the art reviewers who come up with all the adjectives and labels. It’s a sort of lifetime work, batting this stuff away. And then he says, Okay, if you want to say that I had Gauguin on my mind when I escaped to the South Seas, I’ll give you Gauguin, but it’s not going to be what you expect [laughs], and he has these paintings of these appalling people showing their pudenda and drinking beer. Then he says, Well, actually, that’s what Gauguin was really like; that’s what he was up to. [Laughter]

You and he have this extraordinary power of using wit and parody. You must have had a good time talking to each other—

DHI think Ashley only likes me because I share the same birthday as Gauguin. [Laughter]

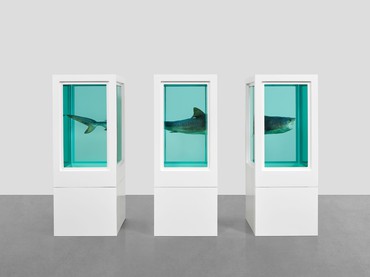

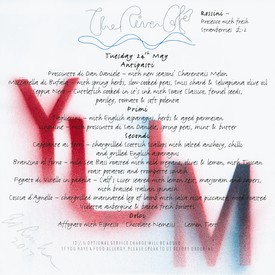

JFRight. He said he had a lot of fun with the exhibition you curated at the Serpentine Gallery, Some Went Mad, Some Ran Away (1994), where he first exhibited a shark, I think—

DHYeah, the hanging black one [Solomon Island Shark, 1993]. I love that work!

JFIt’s so interesting, the different directions from which you both came to sharks. For him it was his trip to Polynesia, and for you, I seem to remember, the aquarium in Leeds.

DHYeah. Poles apart, really, but peas in a pod. I just really felt Ashley’s work. I read in an article that he wrote notes on the back of his works for the installers, and he added buttons you can press on the back that go honk, honk, and there are rattles that make noise when you move them around that only the installers can enjoy.

Angus Fairhurst and I shared a studio at that time and had just bought our first roll of bubble wrap for around forty-five pounds, and we sat in the studio looking at that roll that we’d bought ourselves, paying half each, thinking, We’re real artists now. Before that, I’d been stealing bits of bubble wrap when I’d unwrapped other works in a gallery I worked in. And so I’d gone from that to meeting and hanging out with Ashley, who was really full speed ahead in his career. It was also the beginning of my dilemma about money and art. Ashley made that piece with a counter on it with the price of the work that keeps going up [Composition After William Blake, 1989]. When you buy it, he goes, it’s worth this much, and yet he’s on the move and it’s going up in value and the counter on the work is adding the value at the same rate.

All those things are so fucking inventive and beautiful.

JFYeah, you’re very alike in that way. You were using the same kind of ideas, techniques. He was deliberately making things that provoked the so-called art correspondents—who are different from some very good reviewers who understood his work. I read one critic saying, more or less, “Watch out for Ashley Bickerton. He’s got these kind of secret traps for you. Don’t go there. Don’t review his work. You’re going to make a fool of yourself” [laughs]. That must have happened to reviewers a lot, because Ashley was confounding and confusing people.

DHYeah, but under the guise of truth revealed.

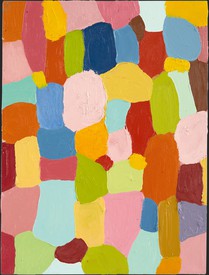

I am obsessed with a simplified earth/sky binary, matter and emptiness, and keep returning to it in a variety of incarnations.

Ashley Bickerton

JFYou came in and out of each other’s lives. He said to me, “I think Damien and I fell out in 1996 when I went off to Indonesia.” And then he said, “He came back to me again, he saw me across some gallery, and it was a sort of reconciliation. We hadn’t talked for a few years.” He was very happy about that.

DH I had a few years where he might have felt I abandoned him, but I didn’t really. I just went full throttle into the drugs and drink, you know. If you weren’t at my speed, I really didn’t recognize you and I lost a lot of people in that period.

JFWell, I would say when I spoke with him, if anything, he was a little pissed off by the fact that you could be, as he described it, scraped off the floor of the Groucho Club, having consumed half the Peruvian Andes, and then had both executable and executed ideas coming out.2 [Laughter]

DHI don’t know how I did that. But I think I got that from Ashley as well. I mean, Ashley was the first artist I knew who had assistants: Roddy [Bogawa] and Bill [Schefferine] for a bit. I realized that his work was created in the same way with assistants—à la Warhol Factory. And Ashley had worked as an assistant, too, back in the day. I remember getting excited to see a show by Jack Goldstein at Waddington Galleries, because somebody had told me that Ashley had been one of this guy’s assistants. I loved that about America. I loved the way that the young assistants worked for the established artists, and then they become artists in their own right. It cycles through the generations; there’s a lineage. Much more than in London.

JFIt’s quite interesting, the parallels in how you both think about painting. Ashley has said, “I am obsessed with a simplified earth/sky binary, matter and emptiness, and keep returning to it in a variety of incarnations.”3 And you’re also wanting always to get back to this simplicity, to solve the problems of painting. It’s fascinating. He talks about the people whom he thinks about, like Turner and Milton Avery, and the title of one of his paintings is Flotsam Painting, After Albert Pinkham Ryder (2019). Here is this guy with massive, elaborate, surrealistic, in-your-face stuff, and he’s going back to this simple canvas idea.

DHI never understood why Ashley went to Bali, apart from the surfing. He does love the ocean. I thought it might be to do with, you know, “Fuck this New York art world bullshit.” I’ve said to him many times, “You’re an American artist, you’re a New York artist.” And he goes, “Look, I was born in Barbados, raised all around, mostly in Hawaii. Bali feels much more like home.” Which is fair, but somehow his work, to me, is always New York. He’s one of the great American artists.

JFYeah, I think so too. He has said that all the motifs for the Bali paintings were already in his head in New York; it didn’t depend on his going into a Gauguinesque tourist horror place. Ashley carries many places with him always. He says that through all these sharp turns, the underlying motor that powers his work is still the same.

It’s very moving the way he talks about his creative impulses. He says, “You want to nail those beautiful things, those ineffable things, and touch that transcendental place, yet still personify those pure disembodied ideas that floated incandescent and untethered in your mind. And then when they land as objects in the world, if they land with grace and seem to float, never quite touching the ground, that’s when you know you’ve done it.”4 I mean, that’s marvelous.

DHUnbelievable. He’s never got it that he’s my hero. I only have a few people whom I’ve admired when I’ve read about them and when I’ve met them, you know, that admiration has carried on or grown. And Ashley’s top of that list. [Laughter]

JFI love Ashley’s deadpan manner. When I was reading some of his writing, I kept thinking of William Burroughs. Burroughs was one of the funniest people on earth. He once said to me that the great disappointment of his life was that he hadn’t been made commissioner for sewers in Saint Louis, which is where he came from. He didn’t smile or anything. And the fact is, he meant there was something serious about this. It was like, I have this patrician background. That’s where I was born. It would have been so much easier slithering around like alligators, as he called it. And then you think, Is he serious? Is he not? And then you think it’s actually very moving. He’s playing with this idea. That’s what Ashley does too. He told Roddy Bogawa: “It took years for me to realize that all my work has always been about parody in some way. And it’s not binary construction of parody; it’s always multi-directional all at once, as often as not, cutting back on or undermining the very premises that it’s setting up. I love playing all sorts of angles with meaning, playing havoc with belief systems, pro and con, being both irrelevant and awestruck in one breath, but always parodistic in nature.”5

DHHe never stops playing. The other thing is he’s instantly recognizable. Some people don’t know who the fuck they are. It’s almost like Ashley’s identity crisis is his logo.

JFThat’s a great point. It is an identity crisis, isn’t it? His father was a linguist, and he was raised hearing different dialects of English across cultures, across the world. You can hear it in his voice. You don’t know what accent he’s using. Where did he get this diction from? It’s from so many unidentifiable identities within him.

DHI remember seeing his self-portraits with the advertising logos on them. He sold advertising space on his own sculptures. [Laughter]

JFThat’s hilarious.

DHHe went to companies and said, Look, I’ve got a show at Ileana Sonnabend’s gallery coming up and I want to sell you advertising space on my work. I want to do some logo paintings on the paintings and, you know, this size is this much and this size is this much, and do you want your logo on my work? Unheard-of thinking.

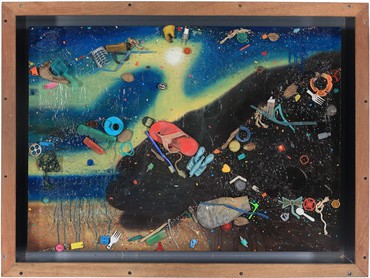

He has another work, called Seascape: Transporter for the Waste Product of Its Own Construction (1986), that does exactly that: it’s a floater, designed to float on the sea, that contains the waste products of its own making for eternity.

JFIt’s brilliant. Regarding his works engaging with the sea, there was a wonderful moment when a reviewer wrote something like, Well, Ashley, with his great love of ecological concerns and saving the planet, is taking up the collective guilt of his generation of art literates. And of course, he isn’t really. The fact is he couldn’t care less about the guilt of the human race. What he loves is nature and its rejection of all this detritus coming up on the shore. He said the planet will survive; it’s just the species that will have to go. And that’s why I find this stuff so beautiful. It’s a part of the cycle of the flotsam.

DHI remember looking at one of his wall sculptures with the canisters you can see through, Catalog: Terra Firma Nineteen Hundred Eighty Nine 01 (1989). It had wood shavings and pebbles and all these natural products inside, and then there were these weird little yellow things that looked like some sort of packing foam. I asked Ashley what they were. And he goes, “Oh those, they’re Cheetos.” [Laughter] What the fuck are Cheetos doing in this ecological piece about the tropical landscape? Other materials include lava stone from the Indonesian mountains. I asked him, How did you manage to get lava stone from the Indonesian mountains? And he said, Oh, it’s just pumice from the local store down the road. I just smashed it all up with Roddy. [Laughter]

JFFor both of you, ideas of exploration, excavation, and archaeology seem to hold a key place in your work.

DHYeah, I think that’s it, isn’t it? It’s the infection that occurs where people and beautiful landscapes meet. I think that’s what Ashley loves. I kind of like that, too.

There is one difference with Ashley which I’ve never understood: I always think that life’s more important than art because art’s about life, whereas Ashley’s got it the other way around—he thinks his art is more important than anything else, including his life. You can even see that going on now as he struggles with his health. He’s more obsessed with making art than anything else right now.

JFIt seems that maybe art is completely tied to life for him—his sine qua non. Here’s another lovely thing he’s said: “I love to communicate, and more than anything I love the idea of transporting people, to move them from point A to point B with knowledge, emotion, and feeling. I don’t know why. I don’t know if it’s even meaningful to do so. Maybe I should just step back and not disturb the universe, but all I ever wanted to do was simply what the likes of Nina Simone and Leonard Cohen have done for me. There is an unwavering need to soar in beauty and to ignite some intangible in the hearts of unknown others. The reasons for this are not clear, but not to do so would be the same as death.”6 In other words, exactly what you just said: “I’ve got to make art or just, you know, nix.”

DHFucking hell. You know what the problem with Ashley is? He’s too good for his own good.

JFTo read that at this moment is so poignant, moving. He’s been making new work throughout his illness, mustering all the human energy to do so, because it’s what he really minds about.

DHHe fixates on the perfection. But really, his works are already perfect. They’re examples of truth revealed in a world where there is no truth. We can’t live without it, and we’re not prepared to accept that there isn’t any.

JFI also don’t think you can have truth without wit. I think somehow wit comes in really fast when there’s truth.

DHWhen I stand in front of any of Ashley’s works—ever since the very early days—I just think, What is this about? I’ve got no fucking clue what Ashley’s work is about, still. There are so many layers. If you think about the Elvis floater [Seascape: Floating Costume to Drift for Eternity III (Elvis Suit), 1992]—

JFOh, yes.

DHIt’s an Elvis suit to float for eternity on the sea. So you go, Okay, I get this, you’re taking something contemporary and you’re transporting it. You’re trying to transport me through time and space through this transportation device. You know, whichever way you get into it, you end up with a bloated Elvis suit in Las Vegas and you’re just going, What am I doing in fucking Las Vegas? Everywhere I turn, I’m in Las Vegas. So what exactly are you freeing me from? Where are you taking me? What’s Ashley trying to do, what’s Elvis trying to do? Is it art or magic or entertainment? Or something else? What’s the connection here? And then you go, Oh, I know what it is, Andy Warhol did those Elvis things; this is Ashley’s version of the Andy Warhol Elvis thing. And then you think, Well, what the fuck are the Andy Warhol things, even? I don’t know what they’re about. That’s Elvis trying to kill you. The whole thing’s just always totally ridiculous. But there’s a real sense of some enormous truth revealed.

JFAshley has said about the Bali paintings, “The viewer is implicated, caught in what might be the bored stares of two bar trollops. You may see the two drunks as fools unable to hold their prizes, the women ripe for predation”—on and on he goes like this—but, he says, “I had the feeling that no one really understood what I was up to in Bali, so I decided I’d create an image of my life that was campy fantasy fiction.”7 In some of the paintings of Bali and the bars, you get a caption underneath.

DHYeah. He gives you the image, which is fucking undecipherable, and you try and decipher it. And then he thinks, Well, people might not be able to decipher this, so I’ll write it for them to help them decipher. So then when you’re reading it, you go, Oh, thank God you explained it because I was getting lost. And then as you read it, you go, I’m still no fucking wiser. What the fuck’s going on? And they won’t let go of you.

JFThen Ashley thinks, Christ, they actually believe this thing too . . .

DHYeah, but that’s what I mean, Ashley’s work is truth revealed. And he goes right back to Magritte’s “This is not a pipe.”

1Ashley Bickerton, interview by the author, April 13, 2016. Subsequent quotations are from this interview unless otherwise noted. Interview © Damien Hirst.

2See also: Bickerton in conversation with Roddy Bogawa, in Ashley Bickerton: Ornamental Hysteria (London: Other Criteria, 2017), available online at https://www.ashleybickerton.net/writings-and-interviews/: “I thought whatever the heck Damien was doing in London at the time, at the height of his wild and wayward ways, was like a great oceanic storm. I didn’t know exactly what Damien was up to but I could feel it. What had started as a drug fueled blizzard of debauchery in the bowels of the Groucho Club in London or wherever they hung out was being transformed over distance into something else, something quite elegant, and whatever energy he was putting out was organizing itself into well groomed wave trains that were breaking mechanically down a reef in my skull. That brutalism had been transformed into something quite elegant, maybe even dainty.”

3“Pictures from a Pandemic: Ashley Bickerton Talks to Anthony Haden-Guest,” White Hot Magazine, October 8, 2020, available online at https://whitehotmagazine.com/articles/bickerton-talks-anthony-haden-guest/4732.

4“Ashley Bickerton with Dan Cameron,” The Brooklyn Rail, February 2022. Available online at https://brooklynrail.org/2022/02/art/Ashley-Bickerton-with-Dan-Cameron.

5Bickerton in conversation with Bogawa,

https://www.ashleybickerton.net/writings-and-interviews/.

6Ibid.

7Ashley Bickerton (London: Other Criteria, 2011), pp. 288, 292.

Artwork by Ashley Bickerton © Ashley Bickerton