Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2023

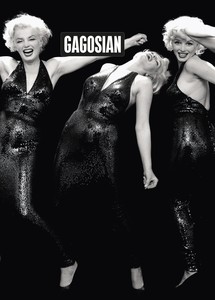

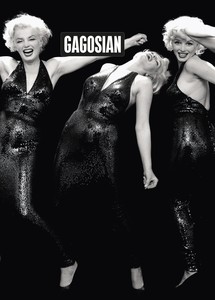

The Summer 2023 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Richard Avedon’s Marilyn Monroe, actor, New York, May 6, 1957 on its cover.

Summer 2023 Issue

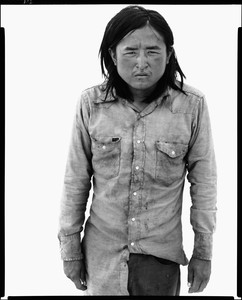

Jake Skeets reflects on Richard Avedon’s series In the American West, focusing on the portrait of his uncle, Benson James.

Benson James, drifter, Route 66, Gallup, New Mexico, June 30, 1979 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Benson James, drifter, Route 66, Gallup, New Mexico, June 30, 1979 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Oil. Rodeos. Drifters. A map to the American West, also called Frontier. We know the myth of it well. Open land for miles. Long horizons only broken by one or two mighty rivers. But there is little water still. There is dirt, and oil and rodeos and drifters. The open road is a metaphor for the opportunity that might exist out west. Out there. Somewhere in the Frontier.

One road is a vein through it all: US Highway 66, also known as Route 66. The Mother Road. According to the National Park Service, there are more than 250 sites along the road that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It’s a road of both myth and history. The road was crucial to the US expansion in the West and contributed to several American industries, like fast food, roadside motels, and Native American jewelry. Entering any gas station or convenience store along the road still offers memorabilia of the all-American story.

Richard Avedon entered this space while working on the series In the American West, stopping by several towns along the road, including small towns like Gallup, New Mexico. Travelers often speed through on their way to Las Vegas or Los Angeles. It’s a town that relies on this travel, both by road and train. One of the revenue streams for Gallup is (American) Indian Jewelry, earning it the nickname “The Indian Capital of the World.” And I consider it one of my hometowns. The other is Vanderwagen, New Mexico, just south of Gallup, located in the checker-boarded area of the Navajo Nation, also known as the Navajo Indian Reservation. For me, it’s Diné Bikeyah, the people’s land. It’s home. Gallup is a border town nestled between the homelands of the Navajo, Hopi, Laguna, Zuni, and Acoma people. It’s the nearest town for a lot of these communities, and families are often forced to travel into Gallup for groceries, supplies, and other amenities. For me, it was all of the above, even schooling. I know Gallup like the back of my hand. I know its history. I know its future.

Avedon visited Gallup in June of 1979. According to Laura Wilson, who worked with Avedon during In the American West, she would often approach subjects Avedon found interesting. While in Gallup, they encountered a man named Benson James. He was wearing a dirty shirt and they photographed him. His face is almost a mirror for the landscape. His face is a reflection of the American West. His hair is shoulder length, and he stands before the white backdrop with the weight of a century. James is holding some crumpled cash in his hand as he stares into the infinity of the camera lens and tells us a story without any words.

James and Avedon represent two histories colliding. In the photograph, we see the visible hand of James and the invisible hand of Avedon. We then see white as if a moment before blackout or death. White like the absent clouds above the western sky. White like foam on spilled beer outside a bar. White like the teeth of pageant queens in Texas or the large letters of small-town pride that are embedded in roadside hills. White like lightning. White like the story of the American West, all boom and roll. James represents the ones who were rolled, and Avedon represents the ones who do the rolling. And I mean this literally. James was murdered a year later in Gallup. Avedon went on to lead a life of celebrated photographs.

I wrote to reclaim the story of my uncle in the way Avedon attempted to reclaim the forgotten stories that exist in the out there.

Avedon’s photographs tell so much of the American story. James’s death tells so much of the American story we all try to forget.

In 1985, my family received the finished book, In the American West. My grandmother had no idea her son, my uncle, had been photographed. My aunt, Paula James, wrote a letter to Avedon, dated February 20, 1985, explaining that James was “stabbed about 40 times behind a Cedar Hills grocery store in Gallup.” My aunt sent the letter from the post office box she still uses today. The letter also inquired about the photo itself, asking if my uncle was paid for his photograph. My mother has a story about my grandmother charging people who wanted to take her picture whenever they traveled into Gallup. Many people wanted photographs of Native people back then. Avedon’s portrait feels different, however. It has a different texture. It has the stain of a forgotten side of American history. The side we lock our doors to, clutch our purses near, pretend we do not notice as we pump gas.

Avedon, in his erasure of background and the orientation of light, situates the American West in an infinite space, both past and present. Our only gesture of time is a face, a stare, a posture, the human body, all beautiful and true. Time is not an experiential element in Avedon’s work. Time is emotive. Time is physical. We can trace time along the photographs themselves. There is no history. There is no destiny. There is only story. And it was this story that moved me when I saw the portrait of my uncle.

I sent several emails to Laura Wilson, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, and the Avedon Foundation during my research into the photograph of my uncle. I wanted to learn as much as I could. I even requested, if there were additional photos taken of my uncle, if I could view them privately. In a previous essay, I wrote about seeing the photograph as a child and again as an adult. I explained, then, that the photograph changed the direction of my first collection of poetry. My book became an investigation into the history of Gallup and my association with the violence that exists there. James’s story is not the only one. It belongs to a long legacy of people dying in Gallup because of alcoholism and racism. Those stories join the many others in various border towns across the United States and Canada. It even joins the hostility in borderlands across the world. Collision, after all, is violent. My first book attempted to write into the turbulence, to offer beauty within the chaos. I wrote to reclaim the story of my uncle in the way Avedon attempted to reclaim the forgotten stories that exist in the out there.

The frontier is my home. I’ve only known collision. My book was an attempt to let the sediment of that legacy settle and hope for a river stone somewhere in the future. Today, as I return to the portrait, I see only the story of my Uncle Benson. I hear the ghost hum of Gallup somewhere in the background. Beyond the white background exists a town that proves time is never what it seems. Time is a road. Time is a building. Time is a turquoise necklace. Time is a gas pump. Time is a body.

One of the kinds of artworks you can find in Gallup are rugs woven by Diné master weavers. They travel through space and time because of their beauty. The designs are everywhere today. One of the prominent designs is the Diné chief blanket with its famous bands of black and white wool. I asked once what the stripes mean. I was told by various people various things. The white and black can represent touch, as in the moment rain hits the ground, or the early morning when the sun is about to rise. And I trace the outline of my uncle’s figure on the white space and observe the same thing: rain, early morning. There is no tragedy in his portrait, only the world, plain as early morning light, an everywhere light.

Avedon 100, Gagosian, West 21st Street, New York, May 4–July 7, 2023

Jake Skeets is the author of Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers (2019), winner of the National Poetry Series, the Kate Tufts Discovery Award, the American Book Award, and the Whiting Award. He is from the Navajo Nation and teaches at the University of Oklahoma. Photo: Bear Guerra

The Summer 2023 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Richard Avedon’s Marilyn Monroe, actor, New York, May 6, 1957 on its cover.

In celebration of the centenary of Richard Avedon’s birth, more than 150 artists, designers, musicians, writers, curators, and representatives of the fashion world were asked to select a photograph by Avedon for an exhibition at Gagosian, New York, and to elaborate on the ways in which image and artist have affected them. We present a sampling of these images and writings.

Wyatt Allgeier discusses the 1984 Arion Press edition of John Ashbery’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, featuring prints by Richard Avedon, Alex Katz, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, and more.

Picasso biographer Sir John Richardson sits down with Claude Picasso to discuss Claude’s photography, his enjoyment of vintage car racing, and the future of scholarship related to his father, Pablo Picasso.

David Cronenberg’s film The Shrouds made its debut at the 77th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in France. Film writer Miriam Bale reports on the motifs and questions that make up this latest addition to the auteur’s singular body of work.

The mind behind some of the most legendary pop stars of the 1980s and ’90s, including Grace Jones, Pet Shop Boys, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Yes, and the Buggles, produced one of the music industry’s most unexpected and enjoyable recent memoirs: Trevor Horn: Adventures in Modern Recording. From ABC to ZTT. Young Kim reports on the elements that make the book, and Horn’s life, such a treasure to engage with.

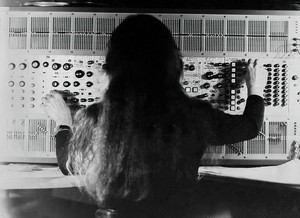

Louise Gray on the life and work of Éliane Radigue, pioneering electronic musician, composer, and initiator of the monumental OCCAM series.

Tracing the history of white noise, from the 1970s to the present day, from the synthesized origins of Chicago house to the AI-powered software of the future.

Ariana Reines caught a plane to Barcelona earlier this year to see A Sea of Music 1492–1880, a concert conducted by the Spanish viola da gambist Jordi Savall. Here, she meditates on the power of this musical pilgrimage and the humanity of Savall’s work in the dissemination of early music.

Dan Fox travels into the crypts of his mind, tracking his experiences with goth music in an attempt to understand the genre’s enduring cultural influence and resonance.

Charlie Fox takes a whirlwind trip through the Jim Shaw universe, traveling along the letters of the alphabet.

On the heels of finishing a new novel, Scaffolding, that revolves around a Lacanian analyst, Lauren Elkin traveled to Metz, France, to take in Lacan, the exhibition. When art meets psychoanalysis at the Centre Pompidou satellite in that city. Here she reckons with the scale and intellectual rigor of the exhibition, teasing out the connections between the art on view and the philosophy of Jacques Lacan.