Nina Simone, Our National Treasure

Text by Salamishah Tillet.

What is crucial to my making of a language and a cosmology of signs is the type of repetition that is central to a lot of the music I am listening to right now. . . . I start off with a limited class of signs and, like stacking in music, I chop and revisit the changes to build structure.

—Ellen Gallagher

Through processes of accretion, erasure, and extraction, Ellen Gallagher has invented a densely saturated visual language in which overlapping patterns, motifs, and materials pulse with life. By fusing narrative modes including poetry, film, music, and collage, she recalibrates the tensions between reality and fantasy—unsettling designations of race and nation, art and artifact, and allowing the familiar and the arcane to converge.

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Gallagher attended Oberlin College, Ohio; artist Michael Skop’s private art school Studio 70; the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (graduating in 1992 and receiving a traveling scholar award in 1993); and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Maine (1993). Her interests in these years spanned across disciplines and time periods, including oceanography, microscopic life, popular media, the poetics of Black vernacular language, and the formal geometries of postwar abstraction. In her first major body of work, made in the mid-1990s, Gallagher applied penmanship paper to canvas in uneven grids, filling the pages with small repeated pairs of stylized lips that she both drew and printed in blue ink. These works thus hinged the aesthetics of 1960s Minimalism to racist minstrelsy and blackface physiognomy. Other biomorphic forms (eyes, tongues, and hair) appear in abstract clusters throughout her oeuvre.

In 1998 Gallagher produced a small group of black monochromatic paintings as a direct response to the critical interpretations of her previous works. Starting again with squares of paper on canvas, she added more geometric shapes, creating a textured terrain that she built up with cut rubber. She further inscribed and collaged aleatory motifs from mid-century American race magazines and other sources, then painted the canvas in layers of black enamel. With this thick, reflective surface, Gallagher suggests that the psychosis of race relations is embedded in the history of Western abstraction.

Gallagher was awarded the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Art in 2000 and began her ongoing Watery Ecstatic (2001–) series the following year. In Watery Ecstatic, she invents complex biomorphic forms that she relates to the mythical Drexciya, an undersea kingdom populated by the women and children who were the tragic casualties of the transatlantic slave trade. Cutting into thick paper in her own version of scrimshaw—the practice of carving whale bones—Gallagher invests the afterlives of the Middle Passage with a sense of material control, her intense focus giving rise to new peripheries. Drexciya is featured again in Gallagher’s film installation Murmur (2003–04), made in collaboration with Dutch artist Edgar Cleijne. Combining celluloid film with computer animation, Gallagher and Cleijne developed an aesthetic that emerges from the intersection of archival sources, fiction, and memory.

Text by Salamishah Tillet.

Jenny Saville reveals the process behind her new self-portrait, painted in response to Rembrandt’s masterpiece Self-Portrait with Two Circles.

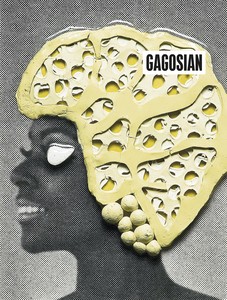

The Summer 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Afrylic by Ellen Gallagher on its cover.

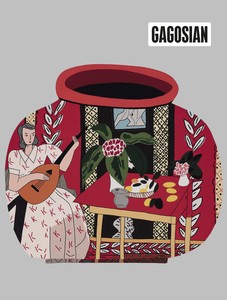

The Spring 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Red Pot with Lute Player #2 by Jonas Wood on its cover.

Ellen Gallagher in conversation with Adrienne Edwards.

Philip Hoare, author of The Whale and The Sea Inside, creates a narrative about Ellen Gallagher’s newest lithograph, Lips Sink.

Request more information about

Ellen Gallagher