About

The combination of red and blue with a creature that has long been thought as a symbol of one’s destiny is my attempt to reaffirm my devotion to art—the creative process for the paintings resembled a prayer offering.

—Takashi Murakami

Gagosian is pleased to present new paintings by Takashi Murakami. This is his first solo exhibition in Rome.

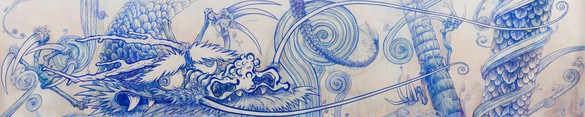

Two epic paintings—Dragon in Clouds – Red Mutation and Dragon in Clouds – Indigo Blue—each comprise nine panels and measure eighteen meters long. Cloud-and-dragon paintings, known as Unryūzu, were also key references for Soga Shōhaku, an eighteenth-century Japanese artist whose eccentric and daring visual inventiveness has been a great inspiration for Murakami. The distinctive representations from traditional Japanese mythology allowed Shōhaku to conjure a fantastic world where overloaded ink drips verge on abstraction, transforming the dragon from more conventional depictions into a vivid, animated monster. Unlike the dragon’s dark associations in Western iconography, the Japanese dragon—an amalgam of the Buddhist iconography that originated in India before reaching China and then Japan—is considered a symbol of good fortune and optimism. Several Buddhist and Shinto temples in Japan are designated as dragon shrines that denote the creature’s exalted status.

While these monochromatic acrylic paintings depart from Murakami’s usual technicolor palette, he continues to draw on a wide range of influences, from Japanese religious symbols to the popular Japanese video game Blue Dragon. In Dragon in Clouds – Red Mutation, the volumetric outlines of energized swirls and vast claws sprawl across the panels while the shaded scales of the dragon’s body replicate the effects of saturated ink in Shōhaku’s paintings. The “red dragon” refers to the eponymous novel by Thomas Harris that hinges on an encounter with William Blake’s Great Red Dragon watercolors as well as the munificent powers associated with it in Eastern culture. In Dragon in Clouds – Indigo Blue, frenetic swirls surround the dragon’s pupils and combine with its flared nostrils and serpentine whiskers to create visual turbulence. The scale of Murakami’s paintings underscores the psychological intensity required to create an image that provoked strong reactions when it was first placed in a Japanese temple centuries ago. In Murakami’s gigantic reimaginings, the dragon becomes a prescient reminder of the intrinsic link between art and the psyche.

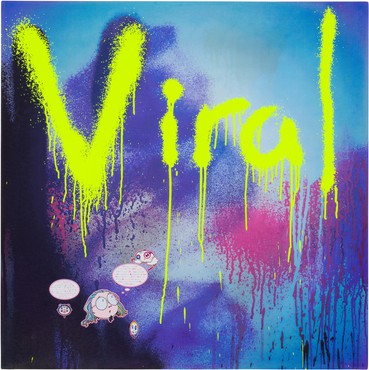

In his distinctive “Superflat” style, which employs highly refined classical Japanese painting techniques to depict a supercharged mix of Pop, anime, and otaku content within a flattened representational picture-plane, Murakami moves freely within an ever-expanding field of aesthetic issues and cultural inspirations. Parallel to the familiar utopian and dystopian themes that feature masses of smiling flowers, elaborate scenes of cartoonish apocalypse, and the ever-morphing cult figures of Mr. DOB, Mr. Pointy, Kaikai, and Kiki, he recollects and revitalizes narratives of transcendence and enlightenment, often involving outsider-savants. Mining religious and secular subjects favored by the so-called Japanese “eccentrics,” nonconformist artists of the Early Modern era commonly considered to be counterparts to the Western Romantic tradition, Murakami situates himself within their legacy of bold and lively individualism in a manner that is entirely his own and of his time.

L’associazione del rosso e del blu con una creatura che per lungo tempo è stata considerata simbolo del destino di ognuno è il tentativo di riaffermare la mia devozione per l’arte: il processo creativo di questi dipinti è stato come un’offerta votiva.

—Takashi Murakami

Gagosian è lieta di presentare due nuovi dipinti di Takashi Murakami in occasione della sua prima mostra monografica a Roma.

Le due imponenti opere, Dragon in Clouds – Red Mutation e Dragon in Clouds – Indigo Blue, sono composte ciascuna da nove pannelli per una lunghezza totale di diciotto metri. I dipinti raffiguranti dragoni e nuvole, conosciuti come Unryūzu, sono stati fondamentali punti di riferimento anche per Soga Shōhaku, artista giapponese del Settecento la cui creatività eccentrica e coraggiosa è stata di grande ispirazione per Murakami. Queste peculiari rappresentazioni della tradizione mitologica giapponese hanno permesso a Shōhaku di immergersi in un mondo fantastico in cui ricche macchie di inchiostro tendono all’astrazione, trasformando il drago in un mostro animato che contrasta con rappresentazioni più benigne e convenzionali. A differenza delle connotazioni negative dell’iconografia occidentale, il dragone giapponese – risultante dell’iconografia buddhista nata in India e migrata poi in Cina e Giappone – è considerato simbolo di buona fortuna ed ottimismo. Numerosi templi shintoisti e buddhisti in Giappone sono dedicati al dragone, denotando così il prestigio della creatura.

Nonostante queste opere monocromatiche in acrilico si differenzino dalla precedente tavolozza multicolore dell’artista, Murakami continua a trarre ispirazione da varie fonti: dai simboli religiosi del Giappone fino al popolare videogioco Blue Dragon. In Dragon in Clouds – Red Mutation, i contorni volumetrici delle energiche forme circolari e dei grandi artigli si distendono sulla tela, mentre il gioco di chiaroscuro delle squame sul corpo del dragone replica gli effetti dei dipinti saturi di inchiostro di Shōhaku.

Il “drago rosso” fa riferimento all’eponimo romanzo di Thomas Harris, ispirato alla serie di acquerelli Great Red Dragon di William Blake, oltre che ai generosi poteri attribuiti dalla cultura orientale a questa creatura. In Dragon in Clouds – Indigo Blue, segni vorticosi circondano le pupille del drago e, assieme alle narici dilatate e ai baffi serpeggianti, creano un turbolento insieme visivo. Le dimensioni dei dipinti di Murakami rimarcano l’intensità psicologica necessaria alla creazione di un’immagine che ha provocato forti reazioni quando fu per la prima volta collocata nei templi giapponesi secoli fa. Nelle rielaborazioni monumentali di Murakami, il dragone diventa un elemento anticipatore del legame intrinseco fra arte e psiche.

Nel suo caratteristico stile “Superflat”, che utilizza raffinate tecniche pittoriche della tradizione giapponese per creare una rappresentazione bidimensionale carica di contenuti pop, manga, ed otaku, Murakami spazia liberamente all’interno di un campo in continua espansione di problematiche estetiche e spunti culturali. Parallelamente ai rinomati temi utopici e distopici che raffigurano masse di fiori sorridenti, fumettistiche scene apocalittiche e le figure cult di DOB, Mr. Pointy, Kaikai e Kiki, l’artista rivitalizza storie di trascendenza ed illuminazione spirituale, spesso includendo ulteriori figure di sapienti. Riprendendo i soggetti religiosi e secolari prediletti dagli artisti giapponesi del periodo moderno cosiddetti “eccentrici” o anticonformisti (comunemente considerati controparte della tradizione occidentale romantica), Murakami si pone nell’eredità di forte individualismo da questi lasciata ma in una maniera che gli è propria e che rispecchia la sua epoca.

Share

Artist

Takashi Murakami and RTFKT: An Arrow through History

Bridging the digital and the physical realms, the three-part presentation of paintings and sculptures that make up Takashi Murakami: An Arrow through History at Gagosian, New York, builds on the ongoing collaboration between the artist and RTFKT Studios. Here, Murakami and the RTFKT team explain the collaborative process, the necessity of cognitive revolution, the metaverse, and the future of art to the Quarterly’s Wyatt Allgeier.

Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2022

The Summer 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, with two different covers—featuring Takashi Murakami’s 108 Bonnō MURAKAMI.FLOWERS (2022) and Andreas Gursky’s V & R II (2022).

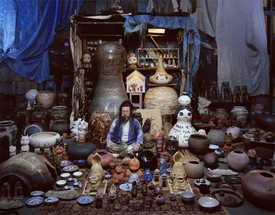

Murakami on Ceramics

Takashi Murakami writes about his commitment to the work of Japanese ceramic artists associated with the seikatsu kōgei, or lifestyle crafts, movement.

In Conversation

Takashi Murakami and Hans Ulrich Obrist

Hans Ulrich Obrist interviews the artist on the occasion of his 2012 exhibition Takashi Murakami: Flowers & Skulls at Gagosian, Hong Kong.

Takashi Murakami at LACMA

In a conversation recorded at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Takashi Murakami describes the process behind three major large-scale paintings, including Qinghua (2019), inspired by the motifs painted on a Chinese Yuan Dynasty porcelain vase.

“AMERICA TOO”

Join us for an exclusive look at the installation and opening reception of Murakami & Abloh: “AMERICA TOO”.