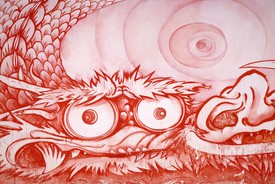

Takashi Murakami earned a PhD from the Tokyo University of the Arts Graduate School of Fine Arts. He began exhibiting his work while still at the university and in 1996 established the Hiropon Factory studio (today Kaikai Kiki) to produce it. In addition to making and marketing Murakami’s art and related work, Kaikai Kiki functions as a supportive environment for fostering emerging artists. With the curation of the 2000 Superflat exhibition, Murakami advanced the Superflat theory of Japanese art. He has exhibited widely both in Japan and overseas. Photo: Claire Dorn

Over the past fifteen years, I have been committed to a number of contemporary Japanese ceramic artists working in the vein of seikatsu kōgei, or lifestyle crafts, organizing their exhibitions, financially supporting their production, and collecting their work. Around 2005, when I started taking an interest in and acquiring ceramics, the world of seikatsu kōgei was at its most exciting, and the artists and their dealers seemed unconstrained and in good spirits. Seikatsu kōgei, in a nutshell, is a movement that attempts to reexamine the beauty of objects of everyday use and to reinterpret this beauty through handcrafting. Many of its proponents also call for environmental sustainability, with a hippieish sensibility.

At the time I became interested in this work, I was completely tied up with the contemporary art market and, moreover, was struggling with theoretical questions with no answers, such as how one might create works that explore the relationship between capitalism and art as their theme. I almost envied the homegrown, organic enthusiasm of the movement.

The 2008 financial crisis devastated the art market in general, and the world of Japanese craft was no exception. Around that time, the seikatsu kōgei philosophy of seihin, honest poverty, started to blossom. Many of the ceramicists in the seikatsu kōgei movement live in rural villages with their families on JPY1.5 million or so (roughly USD14,000) in annual sales. These are artists who minimize their living expenses, turn down work that they don’t like, and feel thrilled, above all, to know that the vessels they make are being used in some household or another.

Support for the forms of cultural expression that represent postwar Japan, including manga, anime, gaming, and seikatsu kōgei, comes from the masses in Japan. In the West, even today, there is a notion that art is something that is supported by patrons. Such patrons have advisors who kindly and carefully explain to them the value of a work in terms of its art historical context, its relationship with contemporary social situations, and art-market trends. If this explanation is convincing, the work is bought and added to the patron’s collection. Art in this case can be both a tool for elevating socialization and a long-term investment. Chances that a work you invest in will become something of worth are slim; one in a thousand might be the odds. But even if just one survives the test of time, it suffices as an investment. Furthermore, you earn respect for fulfilling the duty of an art patron, your contribution boosting the cultural level.

Culture supported by the masses, on the other hand, obviously must be affordable. Even if you want to resell works that you have acquired, there is no market for them at high prices. Nor is there any social merit for purchasing such works. But taking into consideration the feelings one gets when purchasing them, or the fact that one is bidding on the artist’s aspirations when putting down the money, there is no doubt that it is still a transaction of beauty.

This grassroots distribution of beauty came into being and is carried on in a miraculously attractive way, and it sparkled even more brightly after Japan’s so-called bubble economy collapsed. The positive mood around the idea of honest poverty must have appealed to artists, and clients gravitated toward it as well.

The Japanese ceramics industry has, for the past one hundred years or so, been very active on the popular level, and there are many wonderful and affordable works. Yet at the same time, there has been a tendency in the industry to equate affordability with good work, and unfortunately the environment is not set up to allow someone who is talented to pursue and achieve the highest artistic expression within the industry.

Speaking for myself, my career could not have grown to what it is now had I limited my activities to Japan. With the United States as my base, my work has been introduced to audiences globally, and thanks to the efforts of galleries like Gagosian, I have been able to meet clients from around the world. Thriving financially as a result, I have been able to produce a number of experimental works, while simultaneously gaining the courage to continue doing so.

Seikatsu kogei, in a nutshell, is a movement that attempts to reexamine the beauty of objects of everyday use and to reinterpret this beauty through handcrafting.

Hoping, perhaps presumptuously, that I may replicate a similar effect in the ceramics industry, albeit at a smaller scale, I have been commissioning from the ceramic artists I support works in enormous scales and quantities they had never tackled before. In response, each of them has made extremely challenging works, overcoming their previous capacity. Since I ordered these large-scale works knowing that they wouldn’t find any buyers in Japan, I have acquired them all for my collection.

Below, I will further explain the seikatsu kōgei movement and introduce some of the ceramicists I have been supporting over the years: Shin Murata, Yuji Ueda, Otani Workshop, Aso Kojima, Teppei Ono, Atsushi Ogata, and Ryutaro Yamada. They are the artists who have held major solo exhibitions at Kaikai Kiki Gallery, the main gallery among several I operate.

I hope that readers will have the opportunity to experience for themselves the landscape of today’s Japanese ceramics world. And once the pandemic is over, I hope that some of you will travel to Japan, to visit the villages where these artists live and work, and to encounter the environment that gave birth to these creators. There, by enjoying delicious food alongside the vessels they make, you may experience the very essence of Japanese culture and art.

Shin Murata

Of the artists selected here, Shin Murata is the ceramicist I am most committed to, so much so that we have opened a store in Kyoto together; we are basically joined at the hip. The name of our store includes his surname: Tonari no Murata.

The reason I am so supportive of Murata is that he has been highly motivated to produce vessels for upscale kaiseki cuisine, which is unusual for a seikatsu kōgei artist. The idea of seikatsu kōgei is that of the post-bubble economy. Its philosophy is that vessels such as plates and bowls must adhere closely to everyday life and are therefore for ordinary people; it tends to be resistant to high culture. But it is a fact that in Japan there exists this high-end space and occasion in which kaiseki cuisine is served, and I have thought that the philosophy of seikatsu kōgei could contribute to that space. I could sense the same idea from Murata’s work, and when we started talking, we immediately hit it off.

The giant in kaiseki wares was Rosanjin Kitaōji, and so we opened the store in Kyoto with the purpose of pursuing Rosanjin’s world together. We had planned to open a physical storefront earlier this year, in April, but due to the pandemic we had to postpone and have so far been active mainly on Instagram. Once we finally and properly open our doors, my hope is to produce vessels that closely engage with food culture and deliver them around the world.

Otani Workshop

I first went to see an exhibition by Otani Workshop after hearing about an artist who was assisting Yoshitomo Nara with his ceramic works. As rumored, this artist’s sculpture-like ceramic works were in a similar style to Nara’s and had a warm and fuzzy feel to them. He also made plates and bowls, but his stronger works were sculptural in nature. When I asked the artist why, he told me that he had attended an art university in Okinawa, inspired by Alberto Giacometti, but he was told there that a sculptor wouldn’t be able to make a living and so decided to move into the world of ceramics, creating artistic objects while also making plates and bowls. He had already established a peculiar position as an artist, producing and selling dishware but also creating and exhibiting sculptures he loved, and when lucky, making sales.

Otani has since come to be represented by Kaikai Kiki. As he and I continued our dialogue, we talked about him revisiting and exploring his admiration for Giacometti. He now produces ceramic works, paintings, and bronze sculptures, and is becoming a very popular artist.

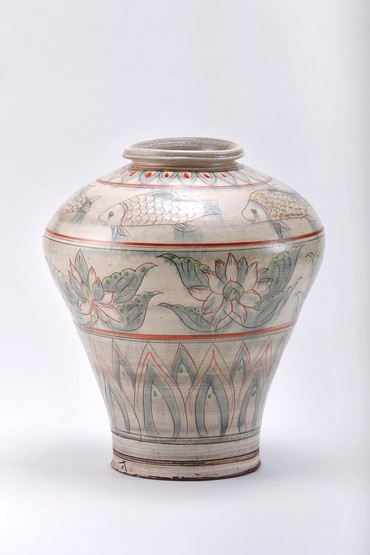

Yuji Ueda

I first met Yuji Ueda because Otani Workshop eagerly wanted to introduce him to me. Ueda’s early works consisted of cracked objects that looked as though they were on the verge of crumbling. Antiques brought in from outside Japan are one of the important motifs of seikatsu kōgei. This includes European furniture, as well as Dutch Delftware, African handicrafts, and Korean antiques, all of which were actively imported into Japan for sale and would sometimes break in the process. Ueda’s objects deform and reinterpret such items, including broken bowls and pieces of furniture falling apart. At first, he made these nonfunctional objects at a small, palm-size scale in large quantities, selling them at stores specializing in pottery. As my interest in seikatsu kōgei at the time was for practical vessels, I didn't particularly care for Ueda’s work initially. But since Otani Workshop would persistently recommend him, I conceded and held a show of his work at the small gallery specializing in ceramics that I used to operate, OZ Zingaro, about ten years ago. On the day of the opening I went to the gallery and Ueda greeted me with a laid-back attitude, saying, “Oh, hi. Thanks for doing the show.” My first impression of him was quite bad. I didn’t like his manner and air of a typical, lackadaisical youth. He then poured some tea for me, which I reluctantly sipped, with a negative feeling, and . . .

“What? What’s up with this tea?” It was so delicious I almost jumped.

It turns out that Ueda had made the teapot and teacup in which he served the tea, and his father owned a tea farm.

“My father grows tea in Asamiya, a little north of Kyoto,” he told me. “We have been growing tea for generations and have received awards as well.”

I took another sip to confirm that the tea was mind-blowingly tasty. And when I looked at Ueda’s works anew after experiencing the delicious tea, they gave me an entirely different impression. It was as though the context started to fall into place in my mind: the multigenerational tea farm → antiques → objects → tea ware → object ware . . . I felt as though I understood the reason he had been producing abstract objects.

That was how we started out. Then two years ago, completely by coincidence, Kanye West was visiting Japan when we had Ueda’s solo show at my gallery, and he stopped by. It was the opening day, and a few works had already sold, but Kanye bought everything that was left. He introduced these works, displayed at his home, on David Letterman’s Netflix show, My Next Guest Needs No Introduction, so some people may have seen them onscreen.

All this is to say, when you see Ueda’s work in person, no further explanation is needed: you just feel the power of his work.

Aso Kojima

Aso Kojima is quite a peculiar artist. He doesn’t call himself a ceramicist but refers to himself as hyakushō. Broadly translated, hyakushō means “farmer” or “peasant,” though the Chinese characters indicate someone who farms but is also capable of performing a hundred tasks. The appellation both laments the tragic status of a farmer who wouldn’t survive unless he were capable of doing everything and proudly boasts that the farmer could do anything. And so Kojima calls himself a farmer and cultivates his fields to be self-sufficient, while building a house and producing ceramics. He also quickly built his own kiln. He is truly dexterous.

Ever since he was little, Kojima had been skeptical about contemporary society; his spirit of rebellion against the system was so strong that he almost dropped out of high school. Once he did graduate, he traveled around Japan and Asia. He worked for ceramic studios to earn some money, and that was how he ended up becoming a ceramicist.

I met Kojima at a solo exhibition of his ceramics, and after that he told me that he no longer wanted to sell his work through a gallery, that he wanted to build a paradise instead. He said he needed some money for that and asked me for financial support. I said no, I couldn’t invest in something that wouldn’t benefit me at all, and asked him why in the world he thought I would give him money. He said, nonchalantly, “I thought you’d be on board because my dream is amazing.”

So I proposed that he produce enough work for me to buy until we reached the amount he desired, and for the next two years, he kept sending me works. With the money he made from these sales, he is currently building his paradise. Paradise, for him, is to acquire some land in a completely uninhabited area of Japan and to live with no interaction whatsoever with other people.

To this day, a year and a half after I finished paying the initial amount he needed, Kojima still contacts me two or three times a year, asking me to buy some works when he needs money, and each time I buy more works. He has completely severed ties with galleries and clients and is maintaining his relationship with me solely for necessary income. Even at my gallery, we held one show of his work, but that was it. His strange mentality gets in the way of doing a show in Japan, so I very much hope to present an exhibition of his work somewhere outside Japan. I really think his works are that of a genius.

Teppei Ono

Teppei Ono has been active since the beginning of the seikatsu kōgei movement. He kindly guided me when I started handling ceramics at my gallery and didn’t know my right from my left. It was Ichiro Hirose, the industry’s cognoscente and the owner of a seikatsu kōgei ceramics store, Toukyo, who introduced me to him.

At the start of his career, Ono produced his work in Tokoname, an area known for its ceramics production, but he eventually escaped from the constraints of this locality, moving to a marginal village in Kochi Prefecture. He has no community of ceramicists around him, and lives and works in an environment where his only daily interactions are with local farmers. His wife is also a creator, making handmade textiles, and they work as a unit. Their career style has cultivated a lot of followers, and today perhaps more than a hundred married couples work and live in this style. But the Onos are the progenitors.

Many of Ono’s fans are rock singers. His works have a bulky and tough style. White rice served in one of Ono’s rice bowls is really exceptional.

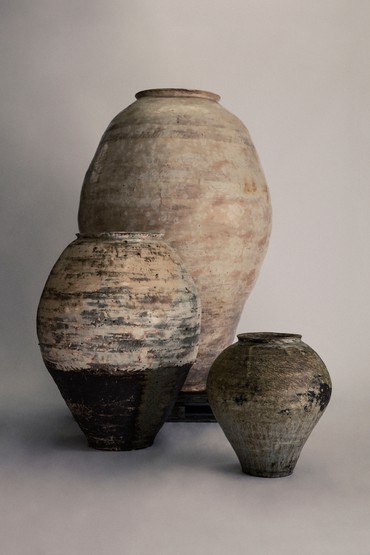

Atsushi Ogata

Until he was around thirty-five, Atsushi Ogata worked as the editor-in-chief of a magazine that captured the Japanese metropolitan life of the 1980s and ’90s. After he became burnt out, he quit his job and became a ceramicist. He abruptly moved to the countryside and plunged into the world of ceramics deep in the mountains of Nara.

One of the things that has left a deep impression on me through my interactions with Ogata is that he has repeatedly told me that his hands are small. “The hands of those who have been throwing pots since their teenage years, always aiming to become ceramicists, grow broad like baseball gloves. My hands, on the other hand, are so ordinary. I’m embarrassed.” Ogata makes large, rough works that seem to attempt to smash this embarrassment and his resentment toward the ceramic industry.

Ogata has created seven or eight enormous pots for me, and in the process of doing so has developed various new techniques. His major inventions have since become a standard format followed by the ceramicists working in the field of seikatsu kōgei.

Ryutaro Yamada

Ryutaro Yamada is the youngest of the ceramicists I’ve highlighted here. When he was in his first year of university, he was struck by a sudden, strange illness, and the resulting physical complex, as I understand it, led him to delve deep into ceramics. Unrelated to this, he is also an artist who has been attempting to pursue the real, hard-core essence of seikatsu kōgei. I say this because there is a part of him that is clearly attempting to revive the format adopted by the late ceramicist Ryo Aoki, who was considered the spiritual pillar of seikatsu kōgei by first-generation proponents like Teppei Ono. Aoki passed away fifteen years ago or so, but Yamada produces his work in the lot in rural Yamanashi that used to be Aoki’s studio.

Currently Yamada is producing one new work after another using three kilns, one built by Aoki and two new ones he made himself. In his communications with me, Yamada has told me that he doesn’t care for it much when people see Aoki’s shadows in his work. Yet I believe he is the artist who has most solidly taken on the concept of seikatsu kōgei in the present. His skills are truly at the level of a genius, yet there is no stage in Japan on which to elevate his gift. For instance, the large-scale works he has made were realized only because I commissioned them; they cannot be sold in Japan. They are marvelously fired, and the works’ exploration of the meaning of ceramics is equally wonderful, yet only small works can be sold here. He hasn’t made any large works since. Even today, Yamada is making plates and bowls to showcase monthly all over Japan in order to make a living. It’s really a pity that such a talent is being wasted (though I don’t think the artist himself agrees with me on this).

Yamada is another one of the ceramicists I dream of showcasing in a major solo exhibition outside Japan one day.