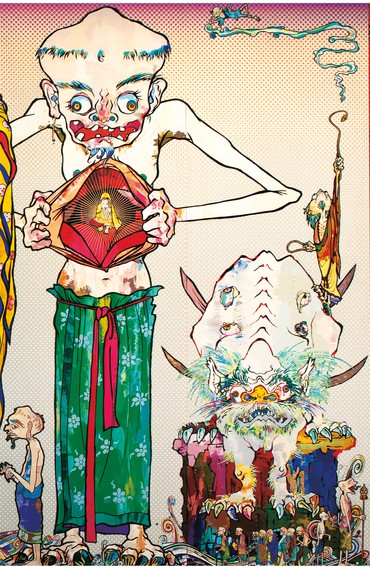

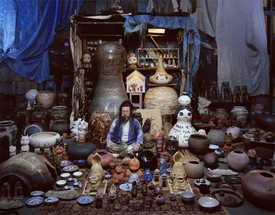

Takashi Murakami earned a PhD from the Tokyo University of the Arts Graduate School of Fine Arts. He began exhibiting his work while still at the university and in 1996 established the Hiropon Factory studio (today Kaikai Kiki) to produce it. In addition to making and marketing Murakami’s art and related work, Kaikai Kiki functions as a supportive environment for fostering emerging artists. With the curation of the 2000 Superflat exhibition, Murakami advanced the Superflat theory of Japanese art. He has exhibited widely both in Japan and overseas. Photo: Claire Dorn

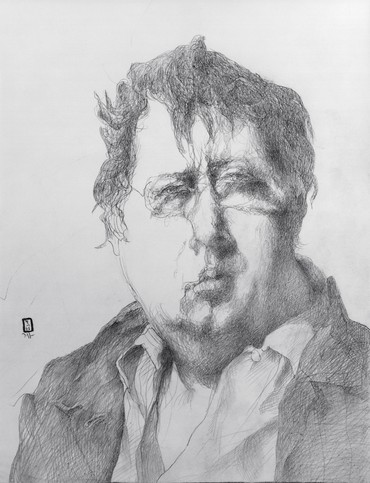

Hans Ulrich Obrist is artistic director of the Serpentine, London. He was previously the curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show), in 1991, he has curated more than 350 exhibitions. Photo: Tyler Mitchell

Hans Ulrich Obrist As a child you wanted to be like—?

Takashi Murakami Having read a lot of biographies and learned about things like Nobel’s invention of dynamite and Madame Curie, I wanted to become an inventor. On the other hand, having read Robinson Crusoe, I also vowed never to board a ship.

HUOWhat was your first museum visit as a child?

TMI think it was probably the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo. I was also often taken to Impressionist exhibitions that were held on the special-events floors of department stores like Mitsukoshi and Takashimaya.

HUOTo begin with the beginning: How did you come to art? How did art come to you?

TMAs I mentioned, I went to shows like the Goya exhibition at the National Museum of Western Art and the Impressionists exhibitions at these department stores—I didn’t really want to go but my parents took me anyway—and when we got home, they would force me to write down my thoughts on what I saw. They wouldn’t let me eat dinner unless I wrote a report. Looking back, I question what sort of educational approach this was supposed to be, but that was my reality. My father loved the posters of The Nude Maja [1797–1800] and The Clothed Maja [1798–1805] that he purchased at the Goya exhibition, and he hung them reverently on the wall, one at a time, alternating between the Nude and the Clothed every few months. I was appalled by this, especially when the Nude was on view. I think it was probably during this period that the idea of art as something grotesque was imprinted on my brain.

HUOWho are the artists who inspired you? Much has been made of the relation of your work to the work of Andy Warhol and his Factory. Is your work also in dialogue with other canonical figures of American art, artists that predate Pop art, like Pollock?

TMThe draftsman and print artist Horst Janssen, who lived in Hamburg, Germany. Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Charles Ray, and Warhol. When I was an art student, the trend was to analyze the minutiae of the American Abstract Expressionist works in unnecessarily complex ways, and though this atmosphere didn’t agree with me, I studied the subject. Warhol was looked down on by the admirers of Abstract Expressionism. In Japan he was known for appearing in a TV ad for videotapes, among other things, and I guess he must have looked dumb to them.

The first time I encountered Warhol was when I saw his paintings of hand-printed dollar bills. There is a Japanese artist named Genpei Akasegawa who had printed Japanese money after the war and lost a court case on the matter, so I became interested. As I learned more, I became powerfully drawn to Warhol’s ideas and his way of thinking. You could say that he was my starting point when I began to form my core values as a contemporary artist.

HUOCan you tell me about the exhibitions that inspired you?

TMTo start with, it was a shocking experience to see that Goya exhibition as a young child. When I saw his Saturn Devouring His Son [1820–23], my father teased me, saying, “In Europe, parents eat their children if the children don’t behave.” I didn’t believe him, but all the same it was very traumatic.

Also, when I was studying to get into art school I saw a Horst Janssen exhibition in Tokyo. I was so moved by the stark and honest way his works presented his hideous life story that it made me cry.

It was after seeing a solo exhibition by the Japanese artist Shinro Ohtake, who makes art from junk, that I decided to become a contemporary artist. His works back then looked like a mishmash of Anselm Kiefer, Sigmar Polke, Julian Schnabel, David Hockney, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, and I was impressed by that very chaos. At the time, most mainstream contemporary art in Japan was made up of imitations of popular artists in the West. There wasn’t much information about their art to be had, and the general mood was that whoever managed to grasp the little information that was available would be crowned the winner.

Then I discovered Kiefer. I went to his large touring exhibition at MoMA and cried, overcome with emotion, in front of Osiris and Isis [1985–87]. The work I had seen in magazines was, in real life, much bigger than I had imagined and I was completely blown away by the scale.

HUOWhat are your favorite museums?

TMMuseum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt is a really great venue. At present, I also think Punta della Dogana in Venice is extremely cool.

HUOCzeslaw Milosz once told me that everyone in the twentieth century was influenced by film. Which films have inspired you?

TMThe Ultraman TV series [1966–67], Close Encounters of the Third Kind [1977], Princess Mononoke [1997], Lord of the Rings [2001–03], Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo [2012].

HUOWhat are your literary influences?

TMShigeru Mizuki [a manga artist], Hayao Miyazaki [manga artist and animation director].

HUOWhat kind of music do you mostly listen to?

TMFishmans, Pink Floyd, Daft Punk.

HUOYou’ve long been interested in Bill Gates’s notion of friction-free capitalism as a business model. Could you talk about this, and perhaps a little about your other inspirations from the world of business?

TMThe minute I finished Gates’s book, I poured my entire savings into buying a computer—that said, I only had enough for one, and it was a Mac.

HUOCan you tell me about how you started off in the art world?

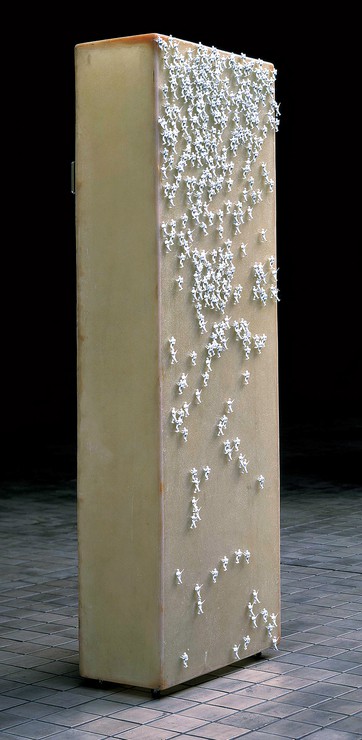

TMIt was with a work called Polyrhythm [1990] with plastic models of American soldiers stuck on a synthetic resin box. It presented the sad tale of Japan as a puppet state that has forgotten the fact that it is in the grip of America, and I believe that, as a theme, the incongruity that accompanies contemplation of the state has been at the basis of my artistic expressions since.

HUOCan you tell me about your earliest works?

TMIt was an extremely stressful period for me; one in which I had great ambitions but was capable only of simple expressions, no matter what I tried.

HUOWhat is the first entry in your catalogue raisonné? The first work you consider valid and no longer student work?

TMIt was a nihonga Color Field painting.

HUOHas the computer changed the way you work?

TMComputers have been the most powerful partner for me in that they enable efficient division of labor. Without computers, it would be impossible to produce my artworks.

HUOIs the twentieth century the century of the collage? And the twenty-first century—?

TMThis is the century in which mankind will venture into outer space in earnest. It’s the century in which we will expose our bodies to cosmic radiation, and it will become difficult to control our life expectancies even with our life-sustaining medicine.

HUOI am very interested in the idea of the manifesto—at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 2008 we held a “Manifesto Marathon”—and I often wonder about its possible future and the potential of this form for the art of the future. Did you conceive your famous essay “A Theory of Super Flat Japanese Art” [2000] as a manifesto? Would you say that it has had a manifesto-like impact and following?

TMYes, I would.

HUOYour essay on Superflat is now thirteen years old. Has your thinking on this theme altered in the intervening years?

TMI am now able to think about various matters in a more complex manner. I have been studying earnestly all along, and it has paid off.

HUOWriting on your art recently, the art historian Pamela Lee linked your theory of Superflat to today’s flattened world of globalized production. How important to an understanding of your visual work is a knowledge of your broader working practice and the world of Kaikai Kiki Co.?

TMWhat you need to know is that I want to (a) approach the great accomplishments of Walt Disney, (b) add to that Duchamp’s humor and Warhol’s devilishness, and (c) do as Steve Jobs did and build a creative business that cannot be copied.

HUOLee also writes of the way that your practice can be read as mirroring aspects of contemporary “post-Fordist” production. In particular, she talks about the interplay of series and the repetition of motifs, on the one hand, and ceaseless variation, flexibility, and adaptation, on the other. Could you talk a little about the importance, for you, of working in series?

TMRepetition is the biggest lesson I learned from the popularity of techno music in the ’90s. I learned that it is bliss for the listener when the same melody is repeated in shifting variations. For a creator, it is also an amazing survival technique that helps you avoid slumps.

HUOScott Rothkopf has compared your Superflat Museum [2003]—a box containing plastic figurines, assembly kits, gum, and certificates—to Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise [1935–41]. Is Duchamp an important figure for you?

TMDuchamp was responsible for bringing humor, in every sense of the word, into art. I aspire to maintain a sense of humor like he did. I would love to create a work that gets discovered after my death, like his peepholes with the painting of female genitalia on the other side.

HUOYou have created a number of characters, such as Mr. DOB and Inochi. You recently worked on your first exhibition in the Middle East, in Qatar, an exhibition entitled Murakami-Ego that featured a giant inflatable self-portrait as a buddha. Could you say, perhaps, that many or even all of your characters have, in some way, been self-portraits?

TMIf we accept that Cy Twombly’s automatic paintings are manifestations of himself, then perhaps my works, too, are self-portraits when seen objectively.

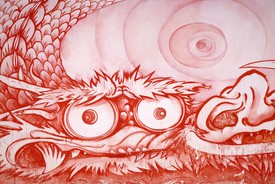

HUOCould you tell me about the 100-meter painting that you presented in Murakami-Ego as a response to the Tōhoku earthquake?

TMAfter the disasters in 2011, I experienced an incredible sense of helplessness. I had no idea what I could do as an artist, and felt that the theories I had been building so far didn’t fit with the post-disaster reality. It was the kind of moment that lies at the origin point of most of the world’s religions. In other words, when we are faced with suffering that we can’t make sense of with the help of the human theories or tools at our disposal, we start to look to things like religion for a sense of healing. But there are also examples of art being used as a platform in these times of crisis, such as with Picasso’s Guernica [1937], and I realized that in Japanese history the three factors—art, religion, and disaster—have always been intertwined. Around that time, I happened to be working with a Japanese art historian on a collaborative serialized column in a Japanese art magazine. The project entailed that for each issue, he would suggest a historical theme and I would make a work in response. The theme he suggested after the disasters was the motif of “arhat.” Specifically, he wrote an essay on Kano Kazunobu’s Five Hundred Arhats [1854–63]. When I saw this, I realized that I had found the platform I was looking for and presented my contemporary version in Doha.

HUOSeveral works from your recent series Flowers & Skulls, shown in Hong Kong in 2012, feature self-portraits. One of these paintings is entitled Self-Portrait of the Manifold Worries of a Manifoldly Distressed Artist [2012]. What is it that you are worried about? What is it that distresses you?

TMI fear old age. Everything I do in my everyday life takes extra time and effort these days. It’s a pain in the neck, and when I’m struck by waves of sorrow at the fact that I will never be my fresh, young self again, it makes me want to cry. But of course even crying won’t console me.

HUOHow did you arrive at the idea for the Flowers & Skulls series?

TMBoth my Flowers and Skulls are popular series, so I thought to create a self-parody by combining the two. However, this was also well received. I suppose this happens a lot in comedy as well. And then when the comedian gets intoxicated by the tunnel vision of these parodies and goes too far, he ends up becoming stale. I suppose that’s me in the near future . . . [laughs].

HUOFlowers and skulls as themes bring to mind a European tradition of still-life painting—in Holland, for instance. Is this something that you are consciously referencing, subverting, or reworking with this series? Is the future invented with fragments from the past?

TM Speaking of Holland, it is known for tulipomania. And I believe that [the speculative tulip market] was the model of the present-day stock market.

Some people desire such changes, some people don’t. I think still-life paintings symbolize the spirit of those who do not desire change. My Flowers & Skulls works are, in that sense, the polar opposite of still-life paintings. I desire change, especially the tendency toward decay.

HUOThere is an “all-over” quality to many of your paintings, something that is especially pronounced in a number of the Flowers & Skulls paintings. This aspect of your paintings seems to reference American Abstract Expressionism as well as the decorative patterns of wallpaper. There also seems to be a nod to Abstract Expressionism in some of your older multipanel paintings, like Cream and Milk, both from 1998. Is this a conscious reference in the work?

TMI consider myself as mimicking Abstract Expressionism. My hope is that by mimicking, I may one day be able to surpass the real thing.

HUOThe series Flowers & Skulls has been written about in terms of eternal themes of life and death, joy and terror. Do you think there is a tension—perhaps an interesting tension—between these humanistic themes and the machine aesthetic of your work?

TMMy desire is always to become a machine that produces artwork. A machine needs to be tuned and maintained, and it requires technical innovations. In this sense, perhaps there is a tension.

I think still-life paintings symbolize the spirit of those who do not desire change. . . . I desire change, especially the tendency toward decay.

Takashi Murakami

HUO Do politics and art mingle?

TMThe question brings to mind Goya’s painting of the massacre by gunfire in Spain. It may not have served any political purpose in that moment, but in the grand scheme of things, I think we can say it succeeded in participating in politics.

HUODoes money corrupt art?

TMNot at all. An earnest creator is always interested in the latest technology, and anything innovative is always expensive, so whatever he does, it costs money. I want to keep up with technological evolution as long as I live. Because of this, I can never have enough money.

HUOWhat role does chance play?

TMEverything. I consider it the same as destiny, and destiny is all there is in this world.

HUOWhat is your motto?

TMArt innovation.

HUODo you have pseudonyms?

TMTakashipom.

HUOWhat is your favorite color?

TMFluorescent pink. Cobalt blue. Gold.

HUOWhat is your smallest work?

TMPerhaps my Shokugan toys [Superflat Museum].

HUOWhat is your biggest work?

TMThe 100-meter-long The 500 Arhats [2012].

HUOWhat is the newest work that you created [in spring 2013]?

TMA series of self-portraits.

HUOWe haven’t talked about your sketches yet. Are you a doodler?

TMAll my works start with small—really small—drawings. I draw a few sketches of just around one to three centimeters square. I almost never doodle.

Though my works start with sketches, I draw them hastily as instructions to my staff, so they are quite abstract. I always wish I had more time to draw.

HUODo you write poems?

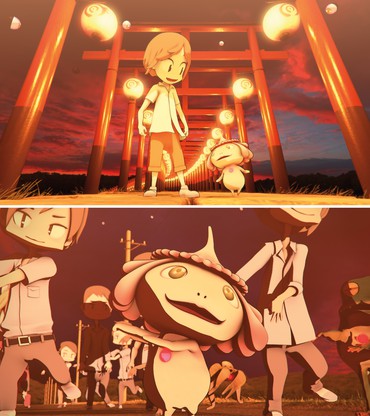

TMI recently composed a song for my film Jellyfish Eyes [2013] and wrote the lyrics as well.

HUOWhat is your dream of happiness?

TMJust as one example: To go back to my youth and sink back into the quagmire that was my love life at the time. Thinking about it in the present, I feel like that’s what it means to really be alive—in other words, even though I was unhappy on the surface, in looking back, I realize that I was happy then. But I do wonder . . . Perhaps happiness is going back and forth between peace and chaos?

HUOWhat is your source of energy?

TMI get my energy first and foremost by watching TV programs about the origin and the end of the universe, and the mechanism that controls them. By learning about how the universe began and how it will end, I aim to gain my own particular understanding of why I am here now.

HUODo you have a typical working day? What would such a thing look like?

TMI wake up in the morning, read emails from my staff, and sometimes respond to them. I give orders to those around me, tweet, and post on Instagram. These days I have postproduction meetings for my film almost every day.

HUOWhat ought to change?

TMMy mindset about internal human resources. To have fresh personnel and to retain experienced staff are two paradoxical concepts. I have to figure out how to manage them and operate in a functional manner while being considerate of my employees’ feelings. Kaikai Kiki Co. is in a transitional period, in that sense.

HUODo you have dreams?

TMI would like to spend a month or so with a peaceful mind, but it is truly an unattainable dream.

HUOWhat are your unrealized projects?

TMFor my film to catch on among the general public and become a big hit.

HUOWhat is your plan for the next years?

TMI want to survive the next burst of the economic bubble. And I want to continue making films.

Collaborating with beautiful people, character actors and actresses, and a variety of talented people is such an exciting thing. I want to keep living in excitement.

HUOWhat does the future hold for Kaikai Kiki Co.?

TMWill it end with my death or continue after I’m gone? This is the question, and I have no way of knowing because it all depends on the fate of the ties I have built with the people around me. It’s all in the hands of the gods. A production company like Disney, which has greatly successful content and can survive even now, is a miracle. Star Wars has been acquired by Disney as well. When I put the question to myself, I have no idea if I want Kaikai Kiki Co. to survive in such a form.

HUOThe future is—

TMI want to try making music. I want to awaken my brain. I don’t do drugs, I don’t drink, and I don’t smoke, so the only pleasure my brain gets is through the production of my artwork. I want some new experiences.

This interview was originally published in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Takashi Murakami: Flowers & Skulls, Gagosian, Hong Kong, November 29, 2012–February 9, 2013

All artwork by Takashi Murakami © Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All rights reserved