The editor-in-chief of artnet News, Andrew Goldstein is a career cultural journalist who has spent the past decade at the vanguard of online art publishing. Previously the chief digital content officer at Artspace | Phaidon, he has written for the New York Times, New York, Rolling Stone, and other publications. Photo: Scott Rudd

Dr. Gail Stavitsky is curator at the Montclair Art Museum since 1994, where she organized Conversion to Modernism: The Early Work of Man Ray (with Francis Nauman), Roy Lichtenstein: American Indian Encounters, and much more. Photo: courtesy Montclair Art Museum

Jeffrey Sturges is the current director of exhibitions for the estate of Tom Wesselmann. He was hired by Wesselmann in 1989 as a studio assistant. He has worked for the Wesselmann family since the artist’s death, in 2004. He was instrumental in overseeing the artist’s first major North American retrospective exhibition tour.

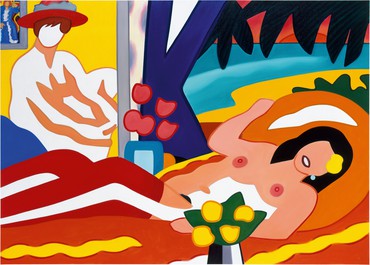

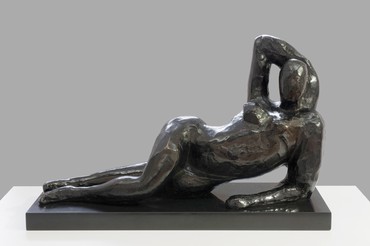

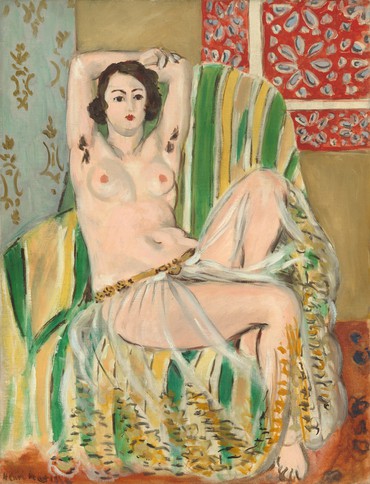

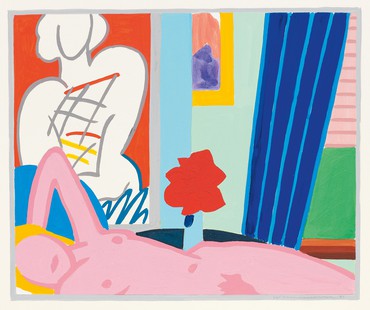

Looking at the clean, sunny compositions and exultant joie de vivre in the work of the American Pop artist Tom Wesselmann, even lay observers might find their minds wandering to the art of another master of the pleasing painting, the French modernist Henri Matisse. From a formal perspective, the two artists share an emphasis on harmony, pictorial economy, and what Matisse called “essential lines”; thematically, both were drawn to the allure of the classical nude—though in importantly different ways. Nor is their relationship across time merely an accident of complementary styles. Wesselmann, from the very beginning of his career to his twilight days, determinedly claimed art-historical descent from Matisse, in the manner of a son demanding rights of succession from a distant father.

How did this unusual relationship across time blossom? Wesselmann originally dreamed of becoming a cartoonist, and studied drawing at the Art Academy of Cincinnati. His ambitions changed, however, after he arrived in New York to attend Cooper Union in 1956 and found himself plunged into the cauldron of that city’s postwar artistic ferment. Impressed by the work of the Abstract Expressionists, in particular Willem de Kooning, Wesselmann felt that “to find his own passion” he needed to “go in as opposite a direction as possible.” Matisse, as an exemplar of the figure-focused generations preceding the New York School, provided a path forward.

To discuss the way Wesselmann contrived to bring Matisse into the very DNA of his work, Andrew Goldstein sat down with Jeffrey Sturges, the director of exhibitions for the Estate of Tom Wesselmann, and Dr. Gail Stavitsky, lead curator of the Matisse and American Art exhibition at the Montclair Art Museum.

ANDREW GOLDSTEINHow did Wesselmann first become drawn to the art of Henri Matisse?

JEFFREY STURGESI want to read something Wesselmann wrote recounting his thoughts, upon completing his studies at Cooper Union in 1959, because I think it gets to the heart of our discussion:

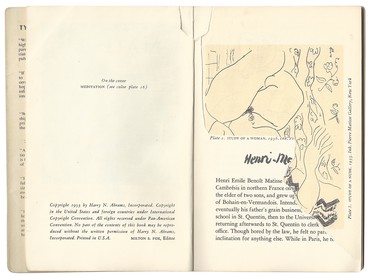

I think Matisse comes in right around the time of graduation from art school. I’d acquired some little cheap book of his reproductions. I’d seen a few here and there before. Obviously I must have. I just didn’t remember them. But having a book in my hand, I got a look at them and they were meaningful to me. I was struck by various aspects of them. I didn’t have too much to say about it, except that I was awed by him as I was by de Kooning. I can sort of look back at whom I was awed by just by saying “Matisse and de Kooning.” What got me about Matisse and put me on my guard at the same time was how very stunningly beautiful his paintings were. They were exciting. You couldn’t look at a Matisse without feeling some kind of excitement, you just couldn’t do it.

You can see Matisse pointing the way, especially in terms of clarity and intense color.

AGWhile Wesselmann considered de Kooning too strong an artistic model to follow, he was less shy about letting Matisse guide his development. Why was he a more sympathetic influence, and what were a few concrete approaches Wesselmann picked up from him?

GAIL STAVITSKYThere’s actually a quote of Wesselmann’s where he said, “I had to find a way of making figurative work exciting, and I certainly got an assist, a morale boost, from his presence.” Pretty early on, I think, Matisse offered a pathway in terms of color and form.

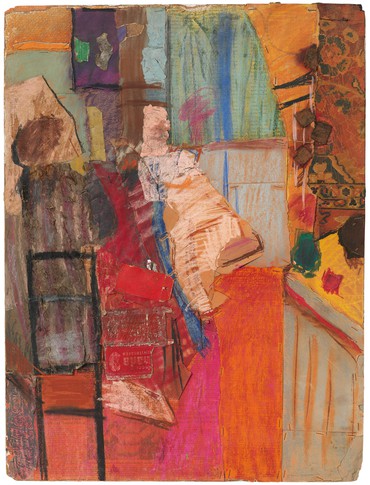

AGWe can see this as early as 1959, when Wesselmann made an important collage titled After Matisse. Can you tell me what’s going on in that work?

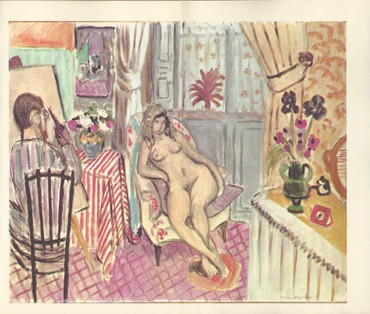

JSWesselmann was copying a Matisse painting called The Artist and His Model [1919]. When you see them side by side, you can find all of the corresponding elements. The thing that’s different is that the Matisse is horizontal, but Tom decides, I’m going to make mine vertical. Clearly he’s trying to understand Matisse’s formal decisions by copying him. But the content is also important—he chose to copy a work whose theme defines his own career, the artist and model.

Another difference is their relationship to the model, and I think that’s significant. Matisse painted his models and then there was Mrs. Matisse. But with Wesselmann, his wife, Claire, was the model for the Great American Nudes, so there’s a personal romantic relationship to the model, which I think is very different from Matisse.

AGThe specific source for the After Matisse homage was a reproduction in Clement Greenberg’s 1953 book Henri Matisse, a resource that Wesselmann would pilfer from at other times as well. Greenberg wrote, “I would say that, for a while now, Matisse has been a more relevant and fertile source for ambitious new painting than any other single master before or after him.” How did Matisse, who passed away two years before Wesselmann came to the city, become so au courant in postwar New York?

GSA lot of that had to do with Matisse’s son Pierre, who moved to New York in 1925, opened a gallery, and did many exhibitions of Matisse’s work. By the late ’40s Greenberg was writing reviews calling Matisse a really important contemporary artist, arguing that he wasn’t just an old modern master but somebody who was still very relevant. Greenberg essentially said that we should rejoice in the fact that Matisse was alive and well and still doing new and important bodies of work, especially those great paintings from 1947 that were shown at the Pierre Matisse Gallery.

AGWhat was the reaction to Matisse’s death like in New York in 1954?

GSThat’s a really relevant question, because it was obviously a moment when a lot of attention was paid to him. One of the works we have in the show is Grace Hartigan’s Homage to Matisse from 1955, so it’s within a year after Matisse’s death. She literally writes right at the bottom of the painting, very boldly, “Homage to Matisse.” It’s her interpretation of his variation on a still life by Jan Davidsz. de Heem, but it’s abstract—the Abstract Expressionist version of that subject. Mark Rothko too painted an Homage to Matisse in 1954. He was certainly on people’s minds.

AGIt reminds me of when the Salon d’Automne held a retrospective of Cézanne in 1907, the year after he died, and all of the modernists in Paris came and were enormously influenced.

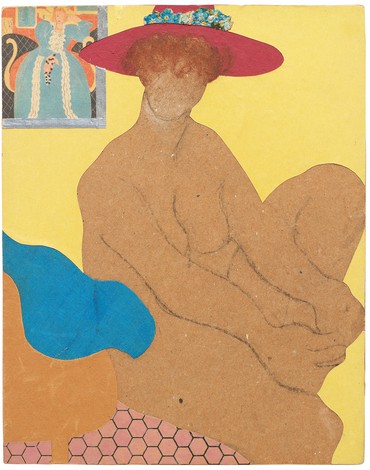

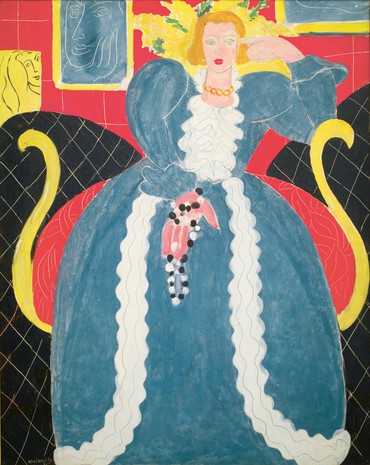

Over these early years, Wesselmann’s kinship with Matisse developed to the point where he seemed to be actively working to claim a kind of art-historical descent from the older artist. In another work from 1960, Judy Trimming Toenails, Yellow Wall, he uses a witty device to connect his more contemporary pictorial instincts to Matisse: he puts a framed Matisse painting in the background, while in the foreground he presents a far more abstracted, featureless nude along with domestic details rendered in shapes of solid color. What is going on in this artwork?

JSWesselmann drew from life. He would make sketchbook drawings, select one that he liked, transfer it to panel, and then add collage elements. In this case we see Judy with a red hat, a blue towel draped over the bathtub, and a yellow wall behind. The color is organized by the triad of those primaries; red, yellow, and blue. On the wall is a reproduction of a Matisse painting showing a woman in a blue dress, with a red chair, and yellow details. This painting also has pictures hanging on the wall. Wesselmann repeats this motif, the painting on the wall, frequently. I look at that Matisse and I see two things. I see Wesselmann questioning himself, like, “Am I up to this?” But then I also a see it as a declaration: “I am this good.” I think he’s saying both. He’s testing himself and answering the question at the same time.

GSIt may also be a kind of dialogue with Matisse in another way, because Matisse so often included his own work in the background. But it’s so clear even from the start here that he’s much more abstract in his treatment of the nude, and also more contemporary, working in the mode of that time period.

AGDo we know specifically what it was that Wesselmann admired so much, or found so useful, in Matisse during this period? What was it that made Matisse into an appealing aesthetic tool for that moment?

JSAs a young artist, Wesselmann felt that the painting he admired, gestural abstraction, was already being done, and seemed to offer no possibilities for him. In the face of a dead end, he decided that the way forward was the opposite: not abstraction but representation. Not brown but colorful. Not messy but sharply defined. I think Matisse offered a model for this new path.

GSMatisse’s flatness, his simplicity of form and palette, and his integration of everything on a two-dimensional surface was so Greenbergian.

AGThe next year, in 1961, Wesselmann’s investigation of Matisse yielded his first big break with Great American Nude #1. It’s clear with this painting and its title that he is placing himself in dialogue with the great European nude, in particular the Matissean nude. And the great American nude is very different. First of all, where does this painting come from?

JSWell, he had a dream. While working on small collage works like Judy Trimming Toenails, Yellow Wall [1960] he began to think more about color and how to use it as a way to define the paintings. He had a dream with the words red, white, and blue and immediately decided to continue the nudes with that theme and the title Great American Nude. Of course he was working in the tradition of the European academic nude, but setting himself apart from it, reinventing it.

AGWhen you think of the search for the great American novel you think of the ideal novel that would tackle the country’s prevailing themes and express its nature. You don’t really think of nude paintings as having the same role in the culture—that there’s a nude out there that will say it all and explain where we are. But the American part of the Great American Nude is what makes it so interesting. How do you see the Americanness of Wesselmann’s nude contrasting with the Europeanness of Matisse’s nudes?

GSIt’s funny because I feel like that’s part of the reason why we’ve talked about this work a lot—there’s something about that whole Hugh Hefner, Playboy, sexy theme, combined with elements of pop culture, that gives it such a uniquely American flavor. It’s interesting to contrast that with Matisse, because sometimes I see his work in terms more of world culture than of European culture. He collected textiles from the Orient and Africa and used all these multicultural elements to inform his paintings, although they’re certainly part of the French tradition of the nude.

JSI think it’s the frankness of the sexuality in Wesselmann’s work that is so different from Matisse’s. There’s an erotic quality—not so overtly at first, but it develops as the series continues. As I said, for Matisse there was Madame Matisse and then there was the model. For Wesselmann there was more of an integration of art and life. He saw eroticism as a very basic facet of humanity, and an important theme in his work—not something off to the side but a driving force, a core component of life.

AGIt’s really fun to look at a Matisse nude and a Wesselmann nude and play a game of compare and contrast. What are the differences? Some are very basic. Matisse’s nudes are brunette, Wesselmann’s are blond. Matisse was a self-avowed romantic, and his nudes are either doing their toilette or posing alluringly, to be admired romantically; Wesselmann’s nudes are far more pornographic, appealing not to romance but to more carnal, libidinal desires—they’re not just for observation. Matisse taps into a classical, almost statuesque ideal of female beauty; Wesselmann was more frank, emphasizing his models’ pubic hair. Then there’s the fact that Matisse uses grand Moroccan villas and country homes as his settings while Wesselmann places his nudes in a tiled bathroom or a kitchen, making them more vernacular and much more direct. Wesselmann even plays up this contrast between the American and the European nude in Great American Nude #44, from 1963, where in the middle of the kitchen there’s a Renoir tondo of a decorous red-cheeked brunette and then on the side you’ve got a featureless blond striking a “rah-rah!” athletic pose. How would you frame this difference between Wesselmann’s and Matisse’s nudes?

GSIt’s much more sublimated in Matisse, because whatever he’s painting is subjugated to balance, harmony, and control, making the whole composition work together. It’s also a personal thing, as you said. I doubt Matisse ever talked about sex the way Wesselmann obviously did, as such an important part of life.

JSThat’s an indicator of the times, right? Think about the sexual revolution—you mentioned Playboy, everything changes in that decade. People are talking about sex. I think this work demonstrates that new openness. There’s a moment in the mid-’60s when Richard Bellamy, Wesselmann’s dealer at the time, says to him, “The more erotic, the better.” Obviously they realized there was a strong response to this aspect of the work, and that people were interested in it. And looking at those Pop artists, Wesselmann went head-on into the subject in a way that none of the others did.

AGMatisse famously said that he dreamed of, “an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or disturbing subject matter, an art which could be for every mental worker, for the businessman as well as the man of letters, for example, a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.” What did Wesselmann hope to provide his viewers?

JSI think it changes. In the beginning he wanted to reproduce the strong visceral response he had had to the work of de Kooning and Robert Motherwell when he was a student, but on his own terms. The Great American Nudes, although unified by the theme of the nude in the interior, are composed of very different materials: painting, photography, real fabric, and objects, each with its own reality. It was shocking to see these realities collide; shocking to see the advertising world and the fine art world collide. Wesselmann was after that kind of shock. But I think this was tempered over time, as his work shifted from collage to pure painting then to the cutout metal works. I think we have to look back again to his early statement about Matisse and beauty. I think beauty in painting was important for Wesselmann too.

AGAre those laser cuts you mention in direct lineage with Matisse’s late cutouts?

JSYes, but Wesselmann brought together several technologies to duplicate his drawings larger than life. So they’re almost photographic in their faithfulness to his original drawings. At the time, thirty years ago, that was a very advanced use of technology. Today it looks fairly commonplace.

MATISSE PAINTED HIS MODELS AND THEN THERE WAS MRS. MATISSE. BUT WITH WESSELMANN, HIS WIFE, CLAIRE, WAS THE MODEL FOR THE “GREAT AMERICAN NUDES,” SO THERE’S A PERSONAL ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIP TO THE MODEL, WHICH I THINK IS VERY DIFFERENT FROM MATISSE.

Jeffrey Sturges

AGAnd even with these very advanced works, Wesselmann is still paying overt homage to Matisse, just as he was in the beginning of his career.

GSIt’s interesting how he always kind of acknowledged the source, as in Still Life with Two Matisses [1991] and Still Life with Johns and Matisse [1992/1993]. It would be absolutely fascinating to see a show just of Wesselmann and Matisse.

AGAbsolutely, that would be a great show. What I love about this late period of Wesselmann’s is that it’s evident he’s having fun with these art-historical allusions and entertaining himself, the way Picasso did in the Vollard Suite, where he was burlesquing his artistic heroes and putting them in wickedly irreverent scenarios. Wesselmann’s sense of humor is different, of course, and in Still Life with Matisse and Johns he approaches his mashed-up theme with a kind of childlike near-abstraction, almost like late de Kooning, where everything is stripped down to its bare minimum. It’s funny to see him start to mix and match his contemporaries with Matisse. What’s going on there? What’s the game he’s playing?

GSI feel like it’s affectionate. There’s also one with Roy Lichtenstein.

JSLichtenstein, Andy Warhol—a lot of his contemporaries are there in the 1990s, it’s not just Picasso and Matisse. It’s a little bit different to see him paired with his peers.

GSYes, that’s why I wondered if it was a kind of friendly mutual admiration.

JSOh yes. It seems like he’s entertaining himself. And they look good, right?

AGThey certainly do. But then the Sunset Nude series [2002–04] is where he really takes a majestic turn, taking on a melancholy, autumnal quality. It’s a poignant series, obviously, because you’ve got the setting sun alluding to his own final years, but it also refers back to the beginning of his career and, of course, to Matisse. Sunset Nude with Matisse Odalisque, for instance, is a sensational painting. But it’s in Sunset Nude with Wesselmann [2003] that he achieves a kind of kaleidoscoping of his whole artistic career, positioning his own Judy Trimming Toenails, Yellow Wall in the background. Presenting that breakthrough 1960 painting, with its own Matisse nestled in its own background, creates a mise-en-abîme effect where you go from a Matisse in a Wesselmann to another Matissean lounging nude—albeit with some tropical, Gauguin touches—in a Wesselmann. It’s moving to see that kind of sweep of his career. What was he thinking about in those final years?

JSWesselmann had a heart attack in the mid-1990s, and here you could make a comparison to Matisse’s health problems. But there’s a sense of renewal that happens after this close call with death. Matisse had that, certainly—the paper cutout series follows that time in his life. Wesselmann, who lived for another decade, went headlong into abstraction and then a new series, the Sunset Nudes. I think he was looking back at the beginning of his career and recognizing what defined him historically as an artist—his Great American Nude series—and as a response he made the Sunset Nudes. Like you said, I think it really is poignant.

And there’s more. One can divide his career into the collage work from 1960–65, the shaped canvases from 1965–85, and then the cutout metal works; each period developed a three-dimensional aspect. Each phase progressed from flat to relief works. His last series, the Sunset Nudes, would have had their own three-dimensional version too, but the series was cut short. He was preparing a series of works based on his early collages, like Judy Trimming Toe Nails, Yellow Wall. He wanted to re-create them on a much larger scale. He had already made preparations for one piece that was a reimagining of a bathtub collage; he had fabricated a giant toilet seat to be included in the work, and was working with his printmaker to fabricate some of the collage material. So the steps were there—he was just gathering the parts, and making studies for works that would have been the assemblage version of the Sunset Nudes.

AGIt sounds like he was about to burst through to some kind of new development.

JSWell, yes, in these last studies one can imagine the next series. It seems so promising.

AGIt’s fascinating then that his career is bookended so strongly by his filial relationship with Matisse. To be honest, I can’t think of any other artist who worked so deliberately in the shadow of an earlier artistic master. At the same time, of course, he was forging his own stylistic path.

JSRight, it’s both. He’s in that shadow but at the same time, he’s clearly himself as an artist. Maybe having such a strong figure to be working against really motivated him. I mean, Matisse is a lot to live up to.

GSYou know, I have to say I think Matisse would have been really happy to have a student like Wesselmann. In Paris he ran a short-lived academy, from 1908 to 1911, and one of the things he really didn’t like was that he felt too many people were copying him and doing their own versions of his bold colors and trying to make their own Matisses. His point was, his teaching wasn’t about copying him, it was about finding your own means of expression. He also used to say, “You have to walk on the ground before you can go on the tightrope,” and he really emphasized the fundamentals, like drawing from plaster casts. It was an almost academic education. I think he’d be very happy to see Wesselmann’s work, because I don’t think he ever wanted anybody to do anything but find his or her own means of expression.

AGAnother interesting corollary to Wesselmann’s late work is Picasso’s late work where he invites a dialogue with the great old masters.

JSThat’s a really good comparison. In the Sunset Nudes, painted in his last few years, Wesselmann included images of other artist’s paintings, hanging on the wall beside the nude. Like the posters of Matisse and Picasso that he had included in the Great American Nudes from the 1960s, these quotations bring those artists directly into his paintings. We see the comparison in the picture, not just in our mind.

AGOf course they have different ways of grappling with their influences. Picasso is looking back at Velázquez and Rembrandt and saying Okay, I’ll do it my way. With Wesselmann it’s more as if he’s saying, the way he had his whole career, I’ll do it the American way.

JSYes. I think the French-American contrast is significant. One of the most important Pop exhibitions was the New Realists show at the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1962, which included the American Pop artists and the European Nouveaux Réalistes. At the time, Wesselmann noted the strong aesthetic difference between the American and the European artists in the exhibition: he described the European artists as too subtle. And his first and most famous series, the Great American Nude, is certainly not subtle.

AGDo we know what Wesselmann thought of Matisse as a man, as a biographical figure?

GSWesselmann said of Matisse, He’s the most breathtaking painter there is—to me. I think that summarizes it all. He was so engaged with the way the work looked, and maybe less so with Matisse as a person.

JSWhat was important to Wesselmann was the art. Being able to meet him? It might have been interesting for him, but I think it was the painting that was engaging, that vibrancy, that vitality.

AGTo go on to the next generation, do any artists come to mind who are indebted to Wesselmann in any way that even approaches the way he was indebted to Matisse?

JSI think Mickalene Thomas’s work shares important elements with Wesselmann’s, the collage aesthetic and the odalisque. She contributed to the Wesselmann retrospective catalogue in 2012. But of course the work is formally and conceptually very different.

AGI also think of Julian Opie as an artist it’s almost hard to imagine without Wesselmann.

JSYes—formally, in terms of the line and even the idea of production. I mean, there were so many times when Wesselmann used technology to advance his work in a way that precedes what Opie is doing today.

AGBut I think it’s undeniable that it’s rare for an artist to have as close a communion with another artist as Wesselmann did with Matisse. The two almost seem fused in Wesselmann’s later work, in a way.

JSYes, I think it grew over the years. In the beginning, you see him including a Matisse poster, and it’s more about making a contrast. But slowly Matisse becomes more and more integrated.

Artwork © Estate of Tom Wesselmann/Licensed by VAGA, New York.

Photos courtesy Estate of Tom Wesselmann unless otherwise noted. All works of Henri Matisse are © Succession H. Matisse, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.