Jacoba Urist is an art journalist living in New York. She has regularly written about art and architecture for The Atlantic, New York Magazine, The New York Times, and Smithsonian Magazine, as well as covered the art market and art news for The Art Newspaper. Urist is a contributing editor for Cultured Magazine, where she profiles contemporary artists.

A month into the pandemic, I arrived in New Haven, Connecticut, to view Titus Kaphar’s latest paintings, From a Tropical Space (2019–)—a series of monumental, almost postapocalyptic images—ahead of an upcoming exhibition at Gagosian, his first solo show since receiving a MacArthur Fellowship in 2018. Just getting into Kaphar’s studio proved to be the trickiest part of the trip. Of course, we had covered logistics: protective masks and latex gloves; maintaining separation; a follow-up conversation on FaceTime. But we forgot about the heavy door, and a flicker of panic ensued as I tried to maneuver an elbow to keep a safe distance between us. “This is a strange body of work,” Kaphar cautioned ahead of our meeting. “It’s a very different approach to making paintings than I’ve used before. This feels like I’ve been dropped into the middle of a film that has been spliced into pieces and that I’m receiving different cells and I don’t know exactly what order they go in, but it’s very clear that they all belong together as parts of a larger story.”

Indeed, From a Tropical Space has haunted me since our visit. Kaphar’s new paintings feel profoundly strange and will confound even those studiously following the artist’s trajectory over the last decade. This seductive body of work is magnificently emotional in a way we have not seen before. Like Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863), or Kerry James Marshall’s School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012), these Kaphars will pull you across the gallery—a visceral reflex more than a cerebral one. My initial, unfiltered thought in their presence: Titus Kaphar has let down his guard. Traditionally, Kaphar invokes old masters to challenge racism in art history. Much of the Western canon represents Black subjects in servitude (including Olympia, of course) or impoverished, if at all. Kaphar’s practice complicates the past, bringing hidden stories to the fore through a rigorous intellectual lens. Take Shadows of Liberty (2016), for example: his first work to combine historical documents and classic portraiture. Kaphar depicts George Washington on horseback—sword drawn, projecting authority—but shrouds the founding father with strips of canvas, each bearing the name of an enslaved person on Washington’s plantation, from a list of over three hundred that the artist discovered on a Mount Vernon farm ledger. Or Shifting the Gaze (2017), a work completed onstage during a TED Talk, wherein Kaphar took white paint to a replica of a seventeenth-century Frans Hals painting, obscuring parts of the composition to shift focus to the Black character. Which is not to say that Kaphar has shied from confronting aspects of today’s America head on, whether police brutality or the prison industrial complex. Yet Another Fight for Remembrance (2014), commissioned by Time magazine, captures Black protestors—arms raised in the “hands up, don’t shoot” position, phones in the air—their truths muted by layers of abstract white brushstrokes. Fusing his own biography with his contemporary twist on classical art, The Jerome Project (2014–) consists of gilded oil portraits based on the mug shots of nearly a hundred African American men who share the first and last names of Kaphar’s estranged father, Jerome, whose prison records inspired the project. Each painting is then partially submerged in tar, to a depth corresponding to the length of time its subject was incarcerated.

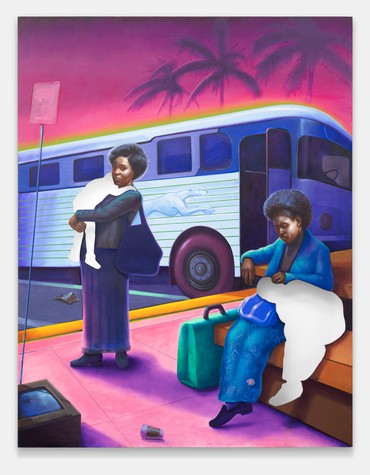

But in New Haven, I found the unexpected—colors too saturated to be conventionally beautiful, images too jarring to call sensuous—and yet, somehow, From a Tropical Space encompasses all of these elements. The story Kaphar is channeling centers around Black women. Child-sized figures are excised from each scene, leaving a ghostly absence in the women’s arms, saddled to their hips, or inside the strollers they push. The timeframe is indeterminate—it could be the 1980s, or perhaps today. The sky radiates pink toxicity; maybe we are in Miami or California, or some parallel reality. A recurring botanical motif in many of the canvases seems artificial and out-of-place, though I can’t pinpoint exactly why. It’s on the wallpaper in one iteration, on pants and jacket in another. I’m not sure when or where we are in space or time, and most of all, what to make of the vanished children. Where have they gone? Do the women know they are missing?

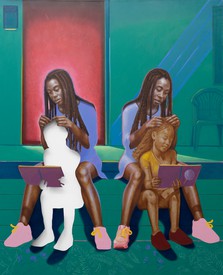

To hear the artist describe the process of creating this series, it has been a visionary one. “The way I understand these paintings now is completely different from when I began,” Kaphar explained, as I stood before the first canvas, trying to get my bearings. “When I first started, I assumed they were about caretakers and nannies.” Yet overcoming the racial bias he brought to these paintings was pivotal to his journey. In fact, for a while, Kaphar felt compelled to put aside the earliest scene—Not my burden (2019), presenting two sisters, an eerie glow emanating from their metallic skin, child-shaped holes resting on their laps—pleased with its formal composition, and intrigued by the strange colors, the florid wallpaper, and the living room portrait, a nod to one of his Whitewash paintings, Family History (2017). But painting domestic workers held no fascination, the subject matter a kind of reinjury for him, given the fraught caricatures of the mammy in Western art. “It didn’t feel right,” Kaphar said. “So I pulled away.” In the second painting, From a Tropical Space (2019) (from which the series title is drawn), the child-shaped holes appeared in the strollers, he explained, making it harder for him to see through the legacy of slavery and the Civil Rights era, or to pretend that he hadn’t “been to an Upper West Side playground on a Monday afternoon.” Only months later did Kaphar realize that the weight of American history was blurring his visual thinking and prohibiting him from identifying the women he was painting as anything but domestic workers. Of the crucial transformation, he shared a journal entry from December:

Somehow I knew intuitively that my inability to see these children as belonging to Black mothers would inhibit the flow of the narrative I was being given and my capacity to read it.

“I just made that first painting and stuck it in a corner,” he recalled. “Once I got beyond the bias, the narrative started to unfold, and I felt that with every painting, another chapter was being delivered to me of this odd story of these Black women.”

Like the lingering stereotypes, the location of this landscape, with its fuchsia smog and wizened palm trees, exacted patience too. “When I got to the third painting, Expecting (2019), I recognized that this wasn’t a geographic place,” said Kaphar, gesturing to the image of a pregnant mother, standing beside a kitchen sink, an absent child against her chest. “Rather, the color I was seeing is a reflection of an emotional and psychological space, an internal geography, where these mothers’ collective trauma crescendos in the disappearance of their Black children.” Within the four corners of this ominous world, there are no White babies; no fathers, though mothers bear young boys. Almost all of these women exist in the moment before their children vanish. The scenes have a foreboding dread, he said, but the ultimate catastrophe hasn’t manifested itself. From a Tropical Space portrays escalating fear. “What is going on in the natural world? Why are all of these mothers so close to this botanical pattern? Think about Katrina or Flint or any other disaster in a poor Black community,” Kaphar continued. “The challenge, however, is to only speak of what I know because there’s so much mystery to me in this work. I want these mothers to speak for themselves.”

Making the series required deep, creative trust and conviction for Kaphar, who likens creating the paintings in From a Tropical Space to that of a writer forced to follow her characters’ particular propensities, listening to their voices for direction. “I’ve never done this kind of exploration from a mother’s perspective,” Kaphar reflected. But as the series progressed, his artistic faith grew. “I feel the best work is made in a state of dialogue, as opposed to a dictated model, when I’m saying to the painting, ‘Alright, what else do you want? Tell me, because I don’t fucking know,’” he said, as I lingered over The Aftermath (2020), which portrays a young mother wearing one shoe, standing amid the chaotic ruins of a home, an open suitcase near her feet filled with water and weighted down by a small island-like boulder. “And the paintings say, ‘Well, just wait, just wait. We’ll tell you.’ That’s the dialogue.” I should be asking more questions, but at several points I catch my breath beneath my mask, desperate to lift it up for fresh air. These tableaux wreck me. Suddenly, I notice I’m crying, telling him about the baby brother I lost as a young girl. “These are all mothers mourning their children,” Kaphar assures me.

There is a subtle irreconcilability to Titus Kaphar. On the one hand, he fiercely loves the history of Western painting; on the other, Western painting has never loved him back. He maintains a strong affection for Matisse, whom he credits, to certain degree, with propelling the series’ emotional use of color. After painting the eerie floral patterns, Kaphar turned to Henri Matisse’s The Red Studio (1911), trying to make sense of what emerged on his own canvas. By far, Kaphar’s favorite artist is the Baroque Spanish painter Diego Velázquez; “I long for a trove of lost Velázquez paintings of Black figures,” he confided to me. Critics, I’m sure, will describe how these latest works condense Kaphar’s art historical knowledge and past technical explorations into an urgent new language that feels unapologetically of the here and now—no longer amending or reckoning with history, but pleading to save a generation of children, such as the missing infant carried by a mother, still tethered to a hospital IV, in Intravenous (2020). “We are talking about COVID at this moment and my work is not about COVID in any way or form,” Kaphar said. “Once again, though, COVID points to the disparity between what’s happening in the Black community and in the rest of the country. Areas of these marginalized communities are not getting what they need.” It is that lived experience of being under siege, the daily wrestle with internalized terror, that lies at the heart of the story he has painted. But for me, his body of work will always be about the last image on the wall: hazy sky, skeletal palm trees, a purple Greyhound bus, and two women, one of whom, seated on a bench, looks down in anguish at the empty hole on her lap. This is the mother, Kaphar believes, who knows her child is gone.

Artwork, unless otherwise noted © Titus Kaphar