Filmmaker Derek Cianfrance most recently directed, wrote, and executive produced I Know This Much Is True (2020), an HBO limited series that features Mark Ruffalo in the Emmy-winning lead role. He also cowrote and executive produced Sound of Metal (2019), which stars Riz Ahmed and Olivia Cooke and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay. Cianfrance’s previous films include The Light Between Oceans (2016), The Place Beyond the Pines (2012), and Blue Valentine (2010). He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, artist Shannon Plumb, and their two sons. Photo: Atsushi “Jima” Nishijima

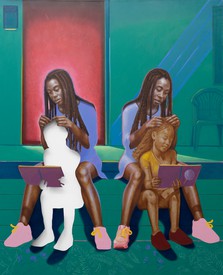

Painter, sculptor, filmmaker, and installation artist Titus Kaphar confronts history by dismantling classical structures and styles of visual representation in Western art in order to subvert them. Dislodging entrenched narratives from their status as “past” so as to understand and estimate their impact on the present, he exposes the conceptual underpinnings of contested nationalist histories and colonialist legacies and how they have served to manipulate both cultural and personal identity. Photo: John Lucas

Kaphar and Cianfrance spoke on the opening night of Titus Kaphar Selects, a film program curated by the artist as part of a series copresented by Gagosian and Metrograph in the spring of 2023. The evening included screenings of Kaphar’s short films Shut Up and Paint (2022), an Oscar-shortlisted work in which he looks to the medium of film in the face of an insatiable art market seeking to silence his activism, and I Hold Your Love (2022), a New Yorker documentary that explores the joys and injustices of Black motherhood. The pair discussed their respective practices, including Cianfrance’s film Blue Valentine (2010) and Kaphar’s film Exhibiting Forgiveness, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival on January 20, 2024.

Derek CianfranceAs a visual artist, what’s drawn you to make films?

Titus KapharI’m a painter. But I’ve realized that the world of painting is really disconnected from the world I grew up in. And I think my short film Shut Up and Paint speaks to that. My other film, I Hold Your Love, is a dedication to motherhood in general, and specifically Black motherhood, and even more specifically, my mother.

DCI’m curious about your process. As a painter, do you feel in control of the paint?

TKI know where you’re going with this. I’m a little bit of a control freak. And yes, in the studio I feel like I have control of that universe to a degree. In the process of making art, you can take complete control of something, but in doing that, you can inhibit your ability to create a masterpiece by controlling every variable. I always say you don’t sit down and make a plan to make a masterpiece. That’s not how it works. You make a plan, but at some point, the muses show up and they say, Yeah, your plan, fuck your plan, we’re going this way. Right? And you have a choice. In that moment, you can say, No, this is my plan—I’m sticking with it. But when you do that, the muses say, Peace, right? They leave.

So, I’ve come to a place in my practice where I’m no longer nervous about that moment. It’s just like, Ah, y’all are here again. You’re about to turn everything up—okay. All right, which way you want to go? What you want to do, let me know. I’m comfortable with that.

DCAnd creating a film is part of a larger collaboration, so you need to work in different ways, perhaps ceding even more control?

TKMaking a film is just different [laughs]. There are a lot of other people and they’re all bringing stuff to it as well. As I was choosing my team to make this new film, I wanted people who understood that we’re going to plan, we’re going to have a backup for our plan, and then when we get into the process, we’re going to listen to the muses. When it’s time to go left because they say go left, we’re going to try left. We just have to. If there’s any possibility of us making something special, it’s going to be because of that, not because we follow the plan by the book.

DCAs part of building your team, how do you think about casting?

TKI’m excited about people who can get in and do the work and bring those characters on the page to life. In no way does it matter to me whether this person has a reputation, has any celebrity, is a “movie star.”

DCStar power.

TKAt the end of the day, I’m not interested in that at all. Except if it’s folks who really care about the project. The irony of it is I feel like I got some stars in the movie I’m currently working on, but it’s because they love what it’s about, care about the vision. Did you see The United States vs. Billie Holiday? Andra Day is starring in my film. Did you see Moonlight? Okay, so André Holland is in my film. Did you see King Richard? Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor is in my film. Those are dope actors.

There’s this weird thing in film where Black actors who are not Denzel Washington don’t get the credit they deserve [laughs]. Those are monster actors right there. They’re absolutely amazing. But if you start talking about the economics of what they bring to the screen, other folks are going to feel some kind of different way and I just don’t want to hear that. I’m not interested in having that conversation at all. So I think we’re making something super special as a result.

DCAnd you’re going to Chicago tomorrow to find an underground theater actor?

TK[Laughs.] That’s not exactly true—I’m going to Chicago to meet with my cousin who just got out of prison. And since I’m going to be in Chicago, there’s this theater actor who nobody really knows, but he did a self-tape for the role of my father. I have some of my producers here, and I promise you, I am not going to cast him tomorrow [laughter]. Some folks are a little nervous because he’s not a superstar, right? But I am interested in what he brought to life on that screen. It was really, really powerful. That’s it. And I can’t believe you just put me on blast like that [laughs].

DCYou mentioned this character is playing your father?

TKYes. Exhibiting Forgiveness is the feature film we’re working on. It’s based on me. It’s a story about an artist who is very successful. He’s kind of made it and as he comes to that pinnacle in his career, his estranged father shows up at his doorstep one day. And really the question of the film is whether or not these two men are going to come back together.

This character, being an artist, is haunted by images of the past. So forgiveness is a challenge in that context, to a visual person, because it’s not just the memory of a thing, it’s seeing the thing that caused you this pain again and again and again in your head. And this particular artist has figured out how to use those images and turn them into paintings; that is the creative process.

DCYou talked about representing the world you know, and now this is getting very, very close to home, like incredibly personal. Is there risk involved? I’m just wondering how that process is going for you and why you’re drawn to doing that.

TKAll of the work I make is really personal. Even the stuff that people think is strictly political is personal. I say this all the time, even Behind the Myth of Benevolence (2014)—which is probably the painting that people know most—came to life out of a conversation with an old white lady, whom I love deeply but we share nothing in common politically [laughs]. I made that painting after a conversation at her breakfast table where she was explaining to me that Thomas Jefferson was a benevolent slave owner. [Audience reaction.] Yeah, that’s what I felt [laughter]. And so I went back to the studio and I made that painting.

Now, when you take it out of the context of that first conversation, it’s just a painting about politics and the history of Thomas Jefferson in this country and so on and so forth. But for me, it was about the relationship I had with this lady. I don’t know how to make work any other way. I’ve tried. It sucks. I don’t think it’s as expressive.

That’s not to say there aren’t difficulties. As we’ve been doing this casting for the film, I’ve sat down with some people, and one of the people that I sat down with, whose name I won’t mention, was so much like my father that it scared me. It made me really, really nervous to even consider casting him for this role. In some ways, I wanted him to get the part because I felt it would be somehow building onto a desire I had as a child to watch my father succeed one time, just get it right one time. But the irony is he was so much like my father that there’s no way he could play the part, because that requires a different kind of effort, a different kind of skill. I couldn’t go through with it. And it would have meant maybe a lot more celebrity brought to the film, but at the end of the day, it was very clear to me that that wasn’t the right decision.

DCI think it was a sober decision you made. There is something in this film that I’ve been impressed with: you have an unresolved story.

TKWhat do you mean?

DCWell, your relationship with your father.

TKAh, yeah.

DCThere is no clean bow on it. There is no resolution. I think movies oftentimes tend toward resolution.

TKDo your films really go toward resolution? [Laughter.] Can we talk for a second for real for real? Let’s talk about Blue Valentine. How did that resolve, bro?

DCThey broke up.

[I’m] letting the art live inside of the cinematic world. . . . They’re paintings that just insert themselves into scenes —they represent the psychological space of the character.

Titus Kaphar

TKYeah, that ain’t a resolution [laughter]. I get it from you, man. I learned it by watching you. I mean, that’s just not life, right? It doesn’t end in a pretty little picture. For me, my story with my father is one where he struggled with an addiction that devastated his life and the people around him. And if you have been a part of that, then you know things don’t generally resolve easy.

So, yeah, thank you for spoiling my film [laughter]. It’s not a happy ending per se. But I think there is some kind of resolution that comes at the end of the film, just not what one would normally think of happening in a film like this.

The other thing I’m excited about in the approach to making this film is letting the art live inside of the cinematic world. I’ve made all the paintings for the film. They’re paintings that just insert themselves into scenes—they represent the psychological space of the character.

DCOne of the lines in your script that really sticks with me is the father telling the son, “I put steel in you.” Implying that this trauma has also given him success.

TKThe sort of irony of my life, and of this story as well, is that as much as I went through with my father, I also recognized that I would not be here if it wasn’t for that. Now, I’m not going to tell him that—shhh, don’t tell him [laughter]. But there is a little bit of truth to what he’s saying. If my father would have raised me to be gentle in the neighborhood that I grew up in, that would have been malpractice. That would have been dangerous for me. And so my father was very hard on me and I survived as a result. I say he went too far at times, for sure, and in the film, you see that. But you don’t see a monster. My father is not a monster. This character is not a monster. He thought he was doing the right thing. That’s really the challenge the character is wrestling with, the reality that at once his father is correct about why he has the ability to do what he does, grind as hard as he grinds, and yet he can’t forget the trauma of those experiences.

DCThere’s a democratization to your work, letting everyone have access to it. You’re also letting everyone really have access to you.

TKNot to me personally, but to the story.

DCTo the story that you’re very close to. I had a similar experience with Blue Valentine. It was one of the things we’ve been talking about: making personal movies, movies that cut so close to the bone it’s almost embarrassing, mortifying to confront. Yet you have no choice but to do it.

TKSo when people see Blue Valentine, do they assume that character is you?

DCBecause he shaved his hair and gave himself a receding hairline like me? [laughter]. Yes.

TKWas that the intention?

DCFor him to shave his hair like—

TKNo, not for him to shave his head [laughs]—for it to be a representation of you?

DCBlue Valentine was based upon my parents’ relationship as seen through the eyes of their child. So that wasn’t them on the screen. That was a projection of myself living a life like I saw them live.

TKThat’s interesting.

DCIt was a cautionary tale for me not to follow that path.

TKDid you feel that you were going in that direction?

DCI had beautiful parents who were great and nurturing. And at the same time, I sat in that back seat, and I studied their arguments. That’s why every shot in Blue Valentine of the arguments is always from the back seat—I had a master class on relationships and arguing. I didn’t want that to happen, so I tried to exorcise it through making a film.

TKThat’s what I feel this process is for me. If I get it out in this way, then maybe it won’t haunt me in the way that it’s been haunting me. And even more so, maybe it can be a gift for others.

DCYes, it’s specific but it’s also open to allow people in—and that was important for me with Blue Valentine as well. I had so many people watch it over the years who related to one character or the other. To answer your question more directly, I don’t see myself as the guy. I relate to the guy and I relate to the girl too.

TKYour films can be kind of dark [laughter]. Would you agree?

DCI don’t know. I mean, they said Muscle [a potential television series about bodybuilding] was a comedy—

TKWait, time out. We’ve been talking about this for a long time. I had no idea it was a comedy.

DCI’ve pitched all my movies as comedies.

TKShut the—there’s no way—

DCThat’s how I get the money.

TKThere’s no way you pitched I Know This Much Is True as a comedy.

DCI did. Mark Ruffalo and I, in the HBO offices, we told them it was a comedy [laughter]. We did.

TKAnybody who’s seen it would be shocked to hear that. You make these films about these really, really dark places.

DCNot anymore.

TKThat’s a lie. And yet you are like one of the kindest people I’ve ever met. I said it earlier today, that you are a special human being. I think it’s part of the reason you’re such a good director—it’s because you’re such a good listener. You have this ability to, at least with me, get me to say shit—I’m like [laughs] I shouldn’t be saying this right now.

We’ve been talking about making personal movies, movies that cut so close to the bone it’s almost embarrassing, mortifying to confront. Yet you have no choice but to do it.

Derek Cianfrance

I feel like your style of directing resonates with how I want to make films. I told Derek—this was really early on—if you made films with more Black people, I probably wouldn’t make movies [laughter].

But one of the things that we’ve talked about is that you do things slightly differently. For example, you don’t generally do table reads.

DCCorrect.

TKAnd you generally don’t do rehearsals.

DCCorrect. Or auditions.

TKCan you talk about that a little bit?

DCWith filmmaking, you have to conjure up this magic, right? You talk about the muses and you want those muses to really come on set and be there, and you only need one moment. I’ve had the experience before with an amazing audition; I would have the recording on my phone or on a video camera, and I’d go around and show people like, Look at this actor, look how amazing this actor is. I would just live in that moment because I wanted to watch it over and over again. And then I would get on set and there was no way to get that moment back, because it existed in this other place and other time. So now I don’t want the magic to come out too soon. I want to save it all up for when the camera’s rolling and just get it one time.

One of the things we first talked about, too, was this idea of legacy. I think that’s what you were attracted to in I Know This Much Is True: the passing on of trauma through generations and how you break it. Epigenetics.

TKExactly. Many of the films we like or talk about or have made are about generational trauma. We’re talking as a society a lot about that phenomenon, and I feel like my film is about how you heal from generational trauma—what it takes to actually get to that place of wholeness and how to pass on levity and joy and hope and kindness to your children.