Bridget R. Cooks is associate professor in the Department of Art History and the Department of African American Studies at the University of California, Irvine. She serves as core faculty in the PhD programs in Visual Studies, Culture and Theory, and the master’s program in Critical and Curatorial Studies. She is author of the book Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum (University of Massachusetts Press, 2011). She is currently completing her next book, titled Norman Rockwell: The Civil Rights Paintings. Photo: Evelina Pentcheva

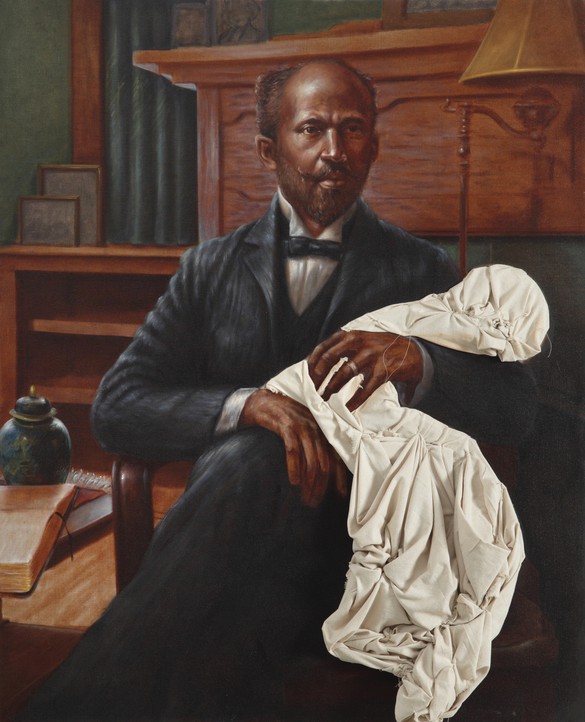

In Titus Kaphar’s painting Father and Son (2010) the artist presents a portrait of the great American philosopher W.E.B. DuBois formally dressed, sitting upright, and proudly cradling a blanket covering a sleeping infant. A second look at this intimate moment shifts the assumption of what was seen at first glance. The blanket is actually a sheet of raw canvas formed into the shape of a baby blanket and stitched onto the painting it hangs from. What initially appeared to be a soft and warm layette painted on the canvas is instead the traditional coarse material of painting—blank and wadded, formless as if ready to be discarded.

The wasted potential of this canvas to take its proper stretched form for painting serves a metaphorical function in Kaphar’s work and in relationship to DuBois’ own paternal history. In his seminal book The Souls of Black Folk (1903), DuBois relates the story of the death of his first-born son, who likely died of diphtheria, a respiratory disease that even at the turn of the twentieth century could have been successfully treated with medical attention. Yet DuBois was unable to find a doctor in time that would treat a black baby. The infant died not of the disease as much as the deliberate discarding of black life, shadowed in insignificance, worthless.

Kaphar’s attraction to DuBois’ work makes sense as it is within Souls that DuBois introduces his concept of the veil, at once a visual metaphor for the social separation of the black and white worlds, and the layers of miseducation and devaluation that disrupt the possibility of visible clarity and lucid communication between the races. Here, Kaphar’s blank canvas is the veil. With it, he creates a portrait of a proud father and a post-mortem memorial of DuBois’ lost son. The blanket becomes the embodiment of an unspeakable loss and the manifestation of the color line. In Father and Son, the canvas serves multiple roles. It is the material of great potential for art, the representation of the first born, and garbage—all layers of the same idea that Kaphar represents effortlessly through his work. The perceptual shifts in the process of looking, the narrative quality, and physical and interpretive layering are consistent features of Kaphar’s art that demand his viewers to engage in lingering provocations.

Through a kind of tender violence, Kaphar emphasizes what is unknown in representations of the past and forcefully argues that our understanding of the past still matters.

Bridget R. Cooks

Kaphar works hard to present the appearance of the truth in painting as his first effect. His paintings offer something familiar to draw the viewer in and, at the same time, offer a deformation. Within a few moments of approaching one of his works, it is clear that something is not quite right. The viewers must labor to deduce what exactly is going on. The persistence of change in Kaphar’s work mimics the revelation of inherited narratives within personal and collective histories that explain how our present came to be. Kaphar shows us that these stories are constructed as deceptively simple truths: the past, like the present, is complex, sloppy, and contradictory; our understanding of history as an easily consumable narrative is often an intricate illusion. The fact that histories have multiple points of view is a given for Kaphar, and his work offers these perspectives for the viewer both to experience and reveal.

Kaphar dismantles the process of perception through various technical and formal gestures in several bodies of work. Throughout these approaches, tension emerges from the uncanny juxtaposition of the familiar and disjunctive. He seductively conjures references to great eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European and American paintings in which well-dressed individuals and families stand contrapposto in the tradition of grand portraiture. Kaphar’s ability to paint in the style of great masters affords his figures, and the stories they tell, a respectable and trustworthy quality spoken in the language of a time-honored tradition of painting. It is easy to be lulled into the safely settled past of these images in which the figures we see sit like still lifes within the frame. They have long since passed from what we decide must certainly have been a simpler time. But to rest there is to willingly stop looking. This peaceful temptation is interrupted by Kaphar’s expressionist treatment of the past. The artist takes this historical representation as a document to look through. He exposes the past as a performance of identity and assembles new objects that visualize the construction of memory. These contemporary works encapsulate the layers of meaning that at first appear coherent.

In All We Know of Our Father (2008) Kaphar literally makes the painting surface protrude, torn and partially digested with a scopophilic desire. In this portrait, only the background and top half of a man’s head is clearly visible. From the nose down, the canvas is a shredded mass. This vandalistic action brings the past forward with force. The representation of the father from what was once a conventionally stoic portrait is undeniably reactivated as both unfinished and dead. The expressionist remaking of the past inspires the viewer to look, decipher, and create new narratives for understanding. Through a kind of tender violence, Kaphar emphasizes what is unknown in representations of the past and forcefully argues that our understanding of the past still matters.

Although primarily a painter, Kaphar is influenced by twentieth-century sculpture (think the crumpled Plexiglass of John Chamberlain): he literally slices his canvases (recall Lucio Fontana’s Spatial Concept paintings), forcing their limits and remaking form. This restlessness with painting is jarring and innovative in its storytelling ability. In Ishmael, His Mother, and His Grandfather (2009), Kaphar uses several techniques to reveal the false modesty of portraiture and the constructedness of family. The title’s biblical reference to Ishmael offers a well-known example of the complexity of family and the feelings of jealousy and shame that can be involved in familial relationships. Brightly painted within an elaborate gilded frame is a portrait of a man, woman, and child. Upon closer view, it becomes evident that each figure appears on a different surface layer, one stacked in front of the other, yet the trio fits together in a familial composition. Furthest back is the image of the woman standing in a bright blue dress beside an elegant potted plant and a palimpsest flurry of white paint covering the trace figure of a man. Standing before her is a young boy positioned tenderly near her arm and spatially in the center of the work. The boy’s delicate silhouette stands free from the painting that he was once a part of. His former context has been cut away and lumped between him and his mother at the bottom of the frame. Like the boy, the man in the foreground of the painting has been removed from a different painting. In his new composition, the man sits pensively in a bright red suit; the quick white de Kooning-like brushstrokes beside the woman in the background seem to explode passionately behind his head. Hanging above him is the negative space of his original canvas drawn up like a theatrical curtain and stuffed into the border at the top of the frame.

Ishmael’s three figures once belonged in their own discrete portraits. Kaphar manipulates those three surfaces to make one—a three dimensional object that shows the relationality between the figures in a new family grouping. He does not try to fully conceal the three contexts of which they were a part; instead, he shows the effort to hide them and their stubborn will to be seen. Set in a wood crate with a protective black velvet lining, this reconfigured family—the result of cutting, smashing, repainting, and stacking—can easily roll back into storage, but this time with the drama of its secrets exposed. The effect of this reconstruction is that a wrong has been made right; the corrected record now shows a family that was not recognized as legitimate in the past. Kaphar’s new object, however, encourages new questions about how family histories are told and who has the right to tell them. Although the three paintings have become one, the figures stand apart, each in its own space. The story is still incomplete.

Artwork © Titus Kaphar; text © Bridget R. Cooks, PhD

This essay is an excerpt from Titus Kaphar: Classical Disruption, published by Friedman Benda, 2011. The full catalogue is available through Friedman Benda.