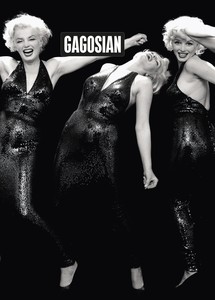

Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2023

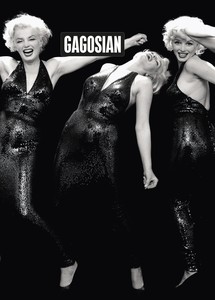

The Summer 2023 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Richard Avedon’s Marilyn Monroe, actor, New York, May 6, 1957 on its cover.

June 23, 2021

This spring, as part of the Lambert Family Lecture Series at the Wexner Center for the Arts, Taryn Simon joined Teju Cole for an online conversation about her artistic practice and creative process.

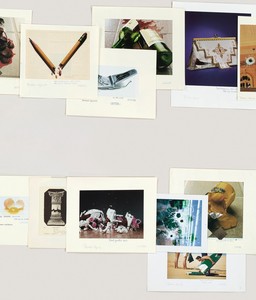

Taryn Simon, details from An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, 2007; A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII, 2008–11; A Cold Hole, 2018; An Occupation of Loss, 2016; and Paperwork and the Will of Capital, 2015

Taryn Simon, details from An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, 2007; A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII, 2008–11; A Cold Hole, 2018; An Occupation of Loss, 2016; and Paperwork and the Will of Capital, 2015

Taryn Simon’s art originates in knowledge systems and informational economies. Making use of photography, installation, sound, video, found material, and other modalities, she constructs research-based schemata that illuminate the contemporary predicament in surprising ways. In the past two decades, she has made a series of meticulous and highly formal works, each radically different from the others, and all of them unfailingly moving. Simon shows time and again that behind the overarching and sometimes oppressive structures that shape society, there are real human beings with irreducible human experiences.

—Teju Cole

Taryn SimonThank you for being “here” with me—in this two-dimensional fantasy.

Teju ColeA fantasy in which the applause we just heard is actually part of a work of yours, Assembled Audience, from 2018.

TSIt’s a synthetic audience generated from applause recorded from a single individual at every event that took place over a one-year period at the three biggest venues in Columbus, Ohio. We collected applause from events like a Katy Perry concert, a Worship Awakening conference, the Ohio Republican Party state dinner, and a conference on glass problems and put them together into an immersive sound installation that reassembles the applause of all these individuals we recorded, who obviously have very different and often clashing ideologies and corporate affiliations and beliefs, into a single manufactured crowd. The room sort of shrinks and expands as you experience the randomizing algorithm that’s assembling all of these different individuals into a group again and again. No crowd gathers the same twice.

TCCan you say a little bit about why Ohio?

TSYes. Well, Columbus in particular is referred to as Test City, USA, and its demographics have been looked to by corporations as a snapshot of the nation and used historically and today to test consumer response to new products from companies like McDonald’s and Victoria’s Secret and Kroger. It’s also a bellwether state that is used to predict election outcomes; every successful presidential candidate in the last two decades has campaigned at one or more of the venues where we recorded.

TCSo, in a way, it is middle America, by various definitions.

TSIt does make you question what those definitions are. In the assembly of all the applause, there’s this kind of obliteration of the individual in the ritual of it all. In recording applause tracks from individuals, the sound each person is making is disassociated from his or her physical self, like a photograph or any other trace.

TCThat’s right. I remember when I first saw the picture of the Republican Party’s state dinner, I had a feeling about it. It’s not just because almost everybody in it was white. There was a “more” there.

Archival documentation of events held in Columbus, Ohio, 2017–18. Left to right: G.I.R.L. 2017; Ohio Republican Party state dinner, August 24, 2018, photo: Joshua A. Bickel, Columbus Dispatch; Justin Timberlake concert, Jerome Schottenstein Center, 2018, photo: Adam Cairns, Columbus Dispatch

TSWhen the recorded applause from that dinner is mixed in with all of the other events that we assembled, it sort of vanishes, but so does the object of the applause. So the politicians, the singers, the basketball players, the business tycoons, they all become these kind of interchangeable or irrelevant figures in rotation. And when you’re standing in that darkened space, you almost become the object of applause. Then the sound itself starts to morph into the natural world. It starts to sound like rain.

TCAnd these photos are actually just research notes; they’re not part of the installation.

TSThey’re not my photographs. They are documentation of the events. For me, the project was always a sonic experience in a pitch-black darkened room with no referent to the space.

TCI think it’s great that we’ve started with this—a lot of people think of you as a photographer and we’ve started talking about a nonphotographic project. You’re more than a photographer, for sure. You’re somebody who’s a thinker with available forms and you’re often in search of what form you can use to convey the thinking around a particular thing.

I want to discuss another one of your projects, Paperwork and the Will of Capital from 2015. In one of the photographs associated with it, [Benito] Mussolini is on the left, and that looks like [Neville] Chamberlain on the right. But who’s the angry guy on the center left cosplaying?

TS[Laughs.] So, it’s Mussolini, [Adolf] Hitler, a German interpreter, and Chamberlain at the 1938 Munich conference.

The Munich Conference, September 1938. Left to right: Italian prime minister Benito Mussolini, German Reich chancellor Adolf Hitler, German Foreign Ministry chief translator Dr. Paul Schmidt, and British prime minister Neville Chamberlain

TCIn a way, it is so typical of the energy that you bring to bear in your work. Nobody looks at this and notices Chamberlain first [laughs]. The first thing they see is the original Nazi himself. But you’re looking elsewhere. You’re actually looking at the flower arrangement. And I see this as one of the core questions of your practice: How does one look elsewhere so that something else can become visible?

So what is the relationship between the flower arrangement here and the rest of what’s going on in the photograph?

TSI saw that image of Mussolini, Hitler, and Chamberlain sitting in a room around this large bouquet of flowers, and it got me thinking about both the performance of power, and nature as this sort of castrated accessory, this silent witness listening to those men and their belief in their abilities to control economies and geographies and the evolution of the world. The bouquets are a constant part of the mathematics of those ceremonies. They serve as this stagecraft of power and how it’s marketed.

Installation view, Taryn Simon: Paperwork and the Will of Capital, United Nations Headquarters, New York, September 10–20, 2016. Photo: Taryn Simon

TCThis is an installation of the works at the United Nations, at a place where certain agreements, certain accords are signed—in this case at the 2016 treaty event concerning human mobility. So, in a sense, the project came back home. It came to a place of power. Do you want to give us just a quick résumé of what went into this project in general?

TSI started researching archival images of signings in which flowers are again and again staged between signatories. I worked with a botanist to identify all the flowers in those photographs, which I then sourced from the largest flower auction in the Netherlands, in Aalsmeer, and had shipped to New York. I re-created the bouquets from those archival images, focusing on signings that took place from 1968 onward and involved countries that were present at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference in New Hampshire, which addressed the globalization of economies after World War II and led to the establishment of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

TCIt encompasses your interest in the movements of persons and goods and agreements.

TSSourcing the flowers from the Netherlands links to the “impossible bouquet” established in early Dutch still life painting alongside early murmurings of capitalism. The term “impossible bouquet” referred to an arrangement of flowers that could never be present in the same time and place due to geographical and seasonal limitations. It was a surreal flower arrangement. Now, these arrangements that were once possible only in the context of a painting can exist in real life thanks to this new chapter of global capitalism in which some can have whatever they want, whenever they want.

Installation view, Taryn Simon: Paperwork and the Will of Capital, Gagosian, West 24th Street, New York, February 18–March 26, 2016. Photo: Rob McKeever

I’m constantly aware of my problems as a photographer or a writer or a maker of anything—of the impossibility of ever achieving precise truth. The effort is to imagine getting to it, through an assembly of the image, the text, the missing things, the slippages.

Taryn Simon

TCWhen I walked into Paperwork and the Will of Capital at a gallery in Brussels in 2016, I was struck not only by the ideas that were being presented, but also by how physically impressive it was. These are huge prints, beautifully framed in wood, and then you have this text on the side that is really meticulous and official. I was just really blown away by it. And, as you know, after the election of [Donald] Trump in 2016, I was thinking I’m not going to write about art. I can’t deal with anything that’s not just a fight right now. I can’t even deal with anything, forget a fight. And that was when I started to write about this work. It was the carefulness of it that got to me.

Can you say something about your choice of language—not just in this project, but in general?

TSThe texts are bound to the act of storytelling but are very worked and, in the end, almost have an un-authored feel because they’re coming from so many different sources. I consciously build contradictions into them. They are restrained but direct. I’m constantly aware of my problems as a photographer or a writer or a maker of anything—of the impossibility of ever achieving precise truth. The effort is to imagine getting to it, through an assembly of the image, the text, the missing things, the slippages.

TCIn Paperwork and the Will of Capital, there are many, many different things that you’re addressing to show the hectic activity that’s going on behind closed doors and how the remains of the day really are always just sort of flowers. They might not soften anything, but they’re always there [laughs].

TSAlways there, but inevitably dying. Many of the agreements represent broken promises—declarations that at the time of their signing were as vibrant and certain as the bouquet itself, preserved in its perfect state by the photograph interrupting time’s continuum. But outside of the image, the withering reflects these broken promises and the irrationality of survival.

Installation view, Taryn Simon: A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, September 22, 2011–January 1, 2012. Photo: David von Becker

TCRight. Your project called A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII [2008–11] also addresses what’s broken, missing. It includes multiple vitrines with portraits inside. There’s a truly awe-inspiring craft that goes into the presentation of your work. It’s like entering the cryochamber of humanity’s truths or something. This is a project that has to do with genealogy and bloodlines, particularly connected to one individual whose story is interesting in some way. Like this fiction of blood around which charts can be drawn—there’s such a thing as a bloodline; people really care about it, these precise relationships. But blood is like the original analog substance. It’s not digital. It cannot be tied down. And you go into some of those contradictions.

One has to do with a man in India who discovered that official records had declared that he was dead, because somebody wanted to steal his land.

TSYes, there was a want to interrupt the hereditary transfer of land by declaring him and other family members as dead. This fiction was complicated through the photograph itself: I was photographing someone who does not exist according to all official paperwork. Within the assembly of each bloodline in the project, different forms of absence appear. There are a number of empty portraits. In this particular chapter, the men who’ve been listed as dead in the local land registry are present, but the living women are not, for religious and cultural reasons. A scaffolding of control surfaces through the absences.

Taryn Simon, Chapter VII, from the series A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII, 2008–11, archival inkjet prints, 3 parts, 84 × 118 ¾ inches (213.4 × 301.6 cm)

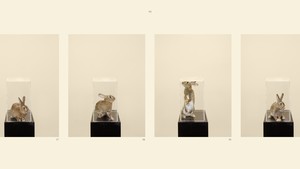

TCThis echoes in the absences in the chapter on the Srebrenica Massacre, which memorializes a genocidal act. Part of what’s painful about this is not only the absences—people who are not there because they’ve died, they can’t be found—but also those who are there as bone fragments, those who are there as little bits of remains. And so, again, I see this project as working on the edge of what photography can do. You’re asking, What is it to make a portrait?

It’s almost as though you’ve got a concept that you want to carefully, almost scientifically pursue. Then, as you pursue it, because you’re also very intuitive, you start to see the edges and the limits of that process, right? If you’re looking at A Living Man Declared Dead, you don’t imagine that you’re going to end up with a chapter on rabbits. But at some point you’re saying, why not? If I’m looking at bloodlines, where does this lead? The project wants to be organized but is always threatening to overspill its borders.

TSAt a certain point, the project just can’t hold itself anymore.

Taryn Simon, Chapter VI, from the series A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII, 2008–11 (detail), archival inkjet prints, 6 parts, 84 × 326 ⅝ inches (213.4 × 829.6 cm)

TCA project of yours from 2007 called An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar includes many different kinds of images. I think if somebody saw any handful of the images, they would not necessarily know what connected them. I do think there’s a consistent photographic style: I can see that things are done very soberly, very cleanly, and there’s a reticence about the images. But what connects them is not super obvious.

TSThose images—both on the wall and in the book—exist alongside text. They are bound to this gap between text and image, which makes me think of your own work because that’s so alive in it. I’m thinking in particular of Blind Spot, where you repeatedly encounter these seemingly quiet images paired with these currents of text. You see the image and you sense, even before reading the text, just by its presence, this charge built up on the surface of the image. And then when you read it, there are all these other dimensions.

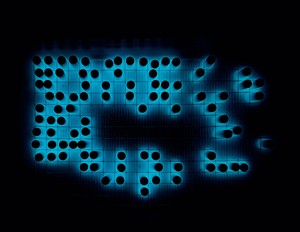

TCI would very much say the same thing about your images, especially in this series. Like the one [Nuclear Waste Encapsulation and Storage Facility, Cherenkov Radiation, Hanford Site, U.S. Department of Energy, Southeastern Washington State] that kind of looks like a map of the United States. I’m like, okay, I’m sitting down, I think I’m ready. Tell me something. There’s something terrible going on, right? And with the image you say, well, yes, it’s a nuclear storage facility in Washington State. If one of those capsules were opened and you were in front of it, you’d be dead in ten seconds.

When I say what connects them is you, I mean that if we think about it, you don’t stroll in with a camera and say, “Can I photograph your nuclear facilities?” I’d love to hear a little bit about your technique. At the end of the day, we see the photos. There’s a lot else that’s going on before the photos are made that is actually integral to how you conceive of yourself as an artist.

TSThe overwhelming bulk of the work is in accessing these sites, in the development of the idea, in the figuring out of where and how it’s going to happen, in the traveling, in the assembly of the data, in interacting with all these different individuals. I consciously erased myself from the work. In some ways that erasure was a refusal to feed the equations that seemed to define women producing art at that time.

Taryn Simon, Nuclear Waste Encapsulation and Storage Facility, Cherenkov Radiation, Hanford Site, U.S. Department of Energy, Southeastern Washington State, 2005–07, from the series An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, 2007, chromogenic color print, framed: 37 ¼ × 44 ½ inches (94.6 × 113 cm)

TCAnd not wanting to be super explicit about that.

TSYeah, exactly.

TCBut when you say you took yourself out of the work, you mean you took your affective response out of the final form of the work. But actually, in a lot of your projects we are invited to contemplate the work that goes into the work. So you don’t take that part out. I don’t know to what extent it’s present in An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, but I think it is, because everything you present is well documented, including documenting the difficulties along the way. So when you take yourself out of the work, yes, the emotional part of it is removed, but not your labor, you know? There’s something almost enjoyable for you when the places you’re trying to get access to make it [laughs]—I’m not saying you’re a masochist, but—make it difficult, right?

TSI am [laughs].

TC[Laughs.] I mean, one must be in order to be a photographer. But, for example, the nuclear storage site in Washington, it’s like, Yeah, sure, come in, take pictures of the nuclear waste—who cares? But then Disney is like, Nope, you can’t come to Disney World, because it’s magic and we can’t have that be seen. That then becomes part of your public record: your attempt becomes part of the story.

TSYes. It took a long while for me to see that. The incorporation of rejections into my work came about in this project and then it bled into future ones. But I have to say, at many points in the four years it took me to assemble An American Index, I really felt the project was falling apart. Only toward its end did I start to recognize that my failures to enter could be incorporated. Then that bled into A Living Man Declared Dead, in which it’s very present.

TCRejections, absences, fraying of the material: when we read a poet like Sappho, we read her as much for the words as for the gaps. Because she invites us to bring our imagination into what’s missing.

I’d also love to hear a bit about your project A Cold Hole, from 2018.

TSMembers of the public are invited to plunge through a floor made of real snow and ice with a hole cut in its center into a dark void of freezing water. When a body hits those freezing temperatures, there’s this extreme gasp that’s only otherwise experienced in birth, death, or sleep arrhythmia. That temperature shock disrupts cognitive processes. The quick fix, the personal reset that the ritual is supposed to deliver comes from overriding your ability to think—I wanted to make that happen within a work.

Installation view, Taryn Simon: A Cold Hole | Assembled Audience, MASS MoCA, North Adams, Massachusetts, May 26, 2018–March 24, 2019

Installation view, Taryn Simon: A Cold Hole | Assembled Audience, MASS MoCA, North Adams, Massachusetts, May 26, 2018–March 24, 2019

TCMembers of the public choose to do it, and they choose to do it in front of an audience in an installation setting.

TSGeronimo used cold water immersion to turn boys into warriors, nineteenth-century asylums used it as a treatment for female hysteria, and Putin chose to plunge into cold water on Epiphany, reenacting Christ’s baptism in the river Jordan instead of watching Trump’s inauguration. In the installation, the performer and the audience are seeking certain kinds of satisfaction. The audience watches the plunger through a cinemascopic aperture. They become rabid and impatient and frustrated when waiting for the individual to jump, and are sometimes forced to wait and watch for thirty minutes as the participant works up the courage to plunge—even then, maybe an audience member looks away for one second and misses it. This irritation and this need to see and consume that moment collides with this spiritual effort in one space.

TCPerhaps this unresolved tension between high aspirations and more quotidian annoyances is also present in A Polite Fiction, from 2014.

TSYes. During the construction of the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, I mapped and excavated and recorded all of these interventions and gestures that the individuals who were hired to build the museum had entombed within the final polished walls of the foundation. Someone painted an abstract oil painting behind drywall, with a message that read, “now I can put on my CV that I’m in the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s permanent collection.” Where the safe was being built, someone wrote a message that says there’s more money in here than in my entire country, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Someone drew over a hundred goats throughout the construction site because he was longing for his goats on his parents’ farm in Portugal. There were political messages about the murder of three Kurdish men, a message with a cigarette left for someone to smoke in the future, pictures of world leaders, messages to aliens. It was just this massive archive—

Taryn Simon, Removed Objects, from the series A Polite Fiction, 2014, archival inkjet prints, in 11 frames, 58 ⅝ × 142 ¼ inches (148.9 × 361.5 cm). Photo: Rob McKeever

TCFrom these people who are construction workers. They’re not “the artists,” but they’re the real artists, because not only are they making the building, but they’re also embedding something of themselves in it, in the fabric of the building. But what you ended up eliciting from it went beyond their writing on the wall.

There are these forms of counter-history that are buried—they’re site-specific gestures, intentional and inadvertent interventions that are now part of the fabric of the place. Then you went further and you started to think about some of the material dispersion of the space as well.

TSExactly. The whole thing felt almost like an inaugural installation before the installation and I was documenting it.

TCIt was then displayed in the Fondation Louis Vuitton itself.

TSYes, it was. And all the gestures that are documented are still there. They’re just not seen. They’re silent. They’re preserved. I always thought about it as almost this energy, this social and political pressure pushing against the walls in some ways.

Taryn Simon and Aaron Swartz, “Borders, 9/30/16, 12:19 PM (Eastern Standard Time),” from Image Atlas, 2012

TCIn thinking about connections within your projects, I was struck by how similar Image Atlas [2012] and The Picture Collection [2013–20] are. Image Atlas, which has to do with the way Google searches in different territories yield different results for the same search term, is a project you made with the programmer Aaron Swartz. And then The Picture Collection has to do with a very extensive picture library that has been kept in the New York Public Library for over a century. With these two titles—Image Atlas and The Picture Collection—one could almost have been run through Google Translate and translated back to arrive at the other.

TS[Laughs.] And they basically were.

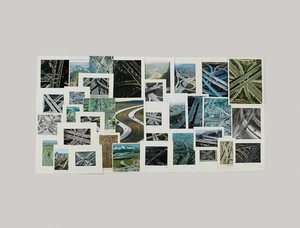

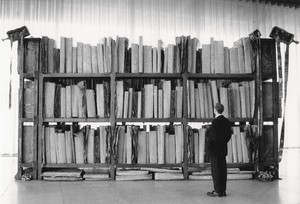

The New York Public Library’s Picture Collection is a precursor to Internet search engines and shows an impulse to archive, organize, and distribute visual material according to a crude algorithm that came long before advanced technological capabilities.

It contains over a million images that are cut from books and magazines. It includes prints and postcards and posters. They’re all organized into more than twelve thousand folders, and each folder is labeled with a subject heading that those images are meant to represent. It was created in 1915, and the public used it to find visual references, which were then transmitted back into American culture, reshaping it in the process. It was a hugely important resource for journalists and historians and filmmakers, and even the military.

Taryn Simon, Folder: Express Highways, from the series The Picture Collection, 2012, archival inkjet print, 47 × 62 inches (119.4 × 157.5 cm)

TCRight. It’s this working collection, but it so happens that some of the pictures in it were made by people like Walker Evans and Berenice Abbott. When they became important artists, that stuff had to be moved elsewhere because those pictures became too valuable to be part of a working collection.

TSExactly, so the collection itself—and its expansion and shrinking as a result of different interventions—becomes this record of a supposed nonhierarchical approach to photography being interrupted by the emersion of marketplace value. Romana Javitz, who built the collection, was a radical figure who is not spoken about in the established history of photography. She insisted on collecting and preserving a history of folk art, documentary photography, and portrayals of African American life long before that became institutional practice. She held all this material for a public to come and sift through and use. It was about the utility of images—pictures as documents.

Installation view, Taryn Simon: An Occupation of Loss, Park Avenue Armory, New York, September 13–25, 2016. Photo: Naho Kubota

TCLet us end as we began: with sound. Tell us about your project, An Occupation of Loss, from 2016.

TSAn Occupation of Loss was first performed in New York. It explores the anatomy of grief and loss and the systems used to manage contingencies of fate. In the performance, professional mourners simultaneously lamented and enacted these rituals of grief in a cacophony of mourning from within eleven concrete pipes with extreme sonic properties. The mourning includes Albanian laments that seek to excavate un-cried words, and Wayuu laments that safeguard the soul’s passage to the Milky Way, where it’s transformed to water and returned to Earth as rain. There are Greek Epirotic laments that bind the story of a life with its afterlife, and Yazidi laments about displacement and exile . . . Lamentation can be a public performance of discontent. In professional mourning a tension is perceived between authentic and staged emotion.

Installation view, Taryn Simon: An Occupation of Loss, Artangel, London, April 17–28, 2018. Photo: Hugo Glendinning + Taryn Simon Projects

TCThat question about authenticity is such an interesting one because, for me, professional mourners are not doing make-believe. They are bearers of needs within a culture, just like a priest is not doing make-believe, and a poet is not doing make-believe. These are moments when people take into themselves some numinous power on behalf of the community.

TSAnd it’s something that is beyond language. An abstract space opens up—and ritual and mourning touch that space. The project insisted on performance for that very reason. It insisted on being beyond the written word, beyond the photograph—it just had to be—

TCHeard.

TSYes.

All artwork © Taryn Simon

This text was condensed and edited from a public talk presented online by the Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio, on March 29, 2021; a recording of the full conversation can be viewed at wexarts.org until March 29, 2022

Teju Cole is a novelist, photographer, critic, and curator. He was the photography critic of the New York Times Magazine from 2015 until 2019. He is currently the Gore Vidal Professor of the Practice of Creative Writing at Harvard University.

Born in New York, where she lives and works, Taryn Simon received a BA in semiotics from Brown University in 1997. In 2001 she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for what would become her first major photographic and textual work, The Innocents (2002), which was exhibited at MoMA PS1, New York. Incorporating mediums ranging from photography and sculpture to text, sound, and performance, each of her projects is shaped by years of rigorous research and planning, including obtaining access from institutions as varied as the US Department of Homeland Security and Playboy Enterprises, Inc.

The Summer 2023 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Richard Avedon’s Marilyn Monroe, actor, New York, May 6, 1957 on its cover.

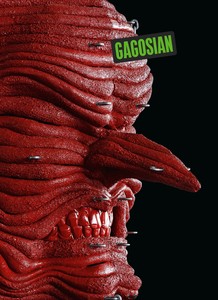

The Fall 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Jordan Wolfson’s House with Face (2017) on its cover.

In Taryn Simon’s performance work An Occupation of Loss (2016), professional mourners enact rituals of grief, simultaneously broadcasting their lamentations from within a sculptural installation. This video by filmmaker Boris B. Bertram documents the April 2018 performance of this work with Artangel in Islington, London.

Joshua Chuang, the Robert B. Menschel Senior Curator of Photography at the New York Public Library, discusses the institution’s singular Picture Collection, the artist Taryn Simon’s rigorous engagement with it, and four instances of its little-known role in the history of art making.

The Summer 2021 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Carrie Mae Weems’s The Louvre (2006) on its cover.

James Lawrence explores how contemporary artists have grappled with the subject of the library.

The Summer 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Afrylic by Ellen Gallagher on its cover.

Two immersive installations by Taryn Simon presented at MASS MoCA in 2018–19 examined the rituals of cold-water plunges and applause. Text by Angela Brown.

Meredith Mendelsohn discusses the impact of Free Arts NYC and its mission to foster creativity in children and teens, on the occasion of its twenty-year anniversary.

Taryn Simon’s 2016 exhibitions spanned the globe. Angela Brown brings us highlights from six museums.

Join Gagosian for a conversation between director, producer, and writer Sophia Heriveaux and actor, director, and writer Roger Guenveur Smith inside the exhibition Jean-Michel Basquiat: Made on Market Street, at Gagosian, Beverly Hills. Heriveaux and Guenveur Smith both share a personal connection to Basquiat: Heriveaux is the artist’s niece and Guenveur Smith was one of his friends and collaborators. The pair discuss Basquiat’s work and legacy, as well as his lasting impact on contemporary art and culture.

Join Brooke Holmes, professor of Classics at Princeton University, and Lissa McClure and Katarina Jerinic, executive director and collections curator, respectively, at the Woodman Family Foundation, as they discuss Francesca Woodman’s preoccupation with classical themes and archetypes, her exploration of the body as sculpture, and her engagement with allegory and metaphor in photography.