Angela Brown is a writer and editor from Yonkers, New York. She is currently a PhD student in modern art history at Princeton University.

Nadie es alguien, un solo hombre inmortal es todos los hombres [Nobody is somebody, one immortal man is all men].

—Jorge Luis Borges, “El inmortal,” 1947

With constant streams of data weaving through our waking and dreaming states, how do we separate the real from the imagined? If there is a line between the two, do we draw it ourselves or is it drawn for us? Taryn Simon continuously asks such questions in her meticulously researched multimedia works. Her photographic projects suggest the impossibility of a universal visual language by revealing how the confines of an image can distort our perception of the world, as well as our place within it.

Photographs today, especially those posted on social media, often seem to present the same scenes over and over, perhaps with slight variations in color, angle, and caption. An enormous and diverse network of people can curate, frame, and edit glimpses of their lives, to be uploaded onto a global platform, an infinite digital archive. At a time when the photographic process is faster than ever, Simon slows it down. By prioritizing research and data collection, she underscores the inherent subjectivity of the medium, showing how combinations of text and image give way to countless contradictions.

In her recent shift toward performance, large-scale installation, and sound, Simon raises new questions about the role of the living, breathing body as an agent within the increasingly pervasive, even ritualized photographic technologies of the past decade. In An Occupation of Loss, which had its second iteration in London in April 2018, she gathered professional mourners from around the world to perform rituals of grief for a circulating audience. Now, in her exhibition at MASS MoCA, which opened in May 2018, she dives even deeper into the societal implications of ritual and performance, complicating the relationship between the private and the public spheres.

Titled A Cold Hole | Assembled Audience, the exhibition includes two new immersive installations: a sound collage of individually recorded applause and a cold-water plunge. By drastically altering the environment of the museum through sound and temperature, and by using architectural elements to frame live actions and sound, these works force the viewer to reconsider the gap between spectacle and spectator, and, in the process, to consider what it means to participate—both in art and in society at large.

In Assembled Audience, Simon presents a public sphere comprised of disembodied applause. The sounds were collected in Ohio, America’s most accurate bellwether state—its population closely matches the demographics of the country as a whole—and specifically in Columbus, which is known to marketers as “Test City, USA” and is a popular location for political campaigns, statistical studies, and the testing of commercial products.1 To make the aural track, Simon worked with a team of local producers to record individual audience members at every event over the course of a year in Columbus’s three largest venues: the Greater Columbus Convention Center, the Nationwide Arena, and Ohio State University’s Jerome Schottenstein Center.2 Participants were separated from their respective crowds and asked to direct their now solitary applause toward a recorder rather than a sports team, political leader, or musician. In this way they acted as representatives of the events that they attended, which included the Worship Awakening Conference, a Columbus Blue Jackets/New York Rangers game, the Black Women Empowerment Conference, the Pretty Princess Parties Columbus Fairytale Ball, a professional bull-riding event, and concerts by the Trans-Siberian Orchestra, The Weeknd, Kid Rock, and Katy Perry. Simon then built a digital program that continually alters our sense of the crowd’s size and response, so that the physical environment we stand in feels as though it is morphing from community-center room to stadium rally to economic forum. Simon also averaged colors from the main interior walls and flooring of the three venues to generate the central prism’s wall color and the color of the carpet. The constructed nature of this resulting “audience” is kept fully transparent: each participant’s name is documented on the gallery wall, along with the name of his or her corresponding event. Though each person matches up with an event, their applause was detached from its cause; instead, they clapped only in order to be recorded.

With “A Cold Hole | Assembled Audience,” Simon makes us absorb information at the pace not of technology or photography but of the mortal body.

Angela Brown

Simon taps into our reflex to mirror the masses, to feel like integral parts of some larger whole. Entering this sonic terrain, one experiences the socially contagious nature of applause, which sometimes arises from heartfelt affirmation but also from discomfort with nonconformity. Community formation and participation, according to political scientist Benedict Anderson, involve ritual, media, and belief. To feel part of a collective unity—a nation, say—an individual must feel “a deep, horizontal comradeship” with all other members of the nation, including the many whom she or he has never met.3 Anderson illustrates this point by comparing a modern ritual—reading the daily newspaper—with a fading one, the recitation of morning prayers. Both are “performed in silent privacy,” he writes. “Yet, each communicant is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands (or millions) of others of whose existence he is confident, yet of whose identity he has not the slightest notion.”4

While Anderson’s prayerful citizen feels connected to a wider community without seeing that community directly, the ubiquity of photographic technologies today makes it possible to see the ways in which our actions either correspond to or differ from those of others. We no longer have to imagine our community because we see it firsthand, or think we do. And yet, despite this apparent ease of participation, the body and mind begin to experience an increased sense of isolation. In this way, contributing to the digital archive is similar to clapping into a recording device: a lot of participation, but no clear purpose.

Yet we keep participating, seeking an avenue through which to find something to believe in. With A Cold Hole, Simon creates a situation in which individuals can willingly abandon conscious thought in order to experience a mental and physical reset, taking the body down to its most basic truth: the fact that it exists. A Cold Hole replaces the gallery floor with a huge frozen-over body of water. One at a time, visitors and performers are invited to enter the stark white room and jump through a hole cut in the ice. The shock of the water effectively turns off the mind for an instant, forcing the body to survive without it.

The practice of cold-water plunges can be traced back to antiquity, serving to renew strength, ward off illness, and provide energy and vigor. When the body enters the freezing water, its systems begin to slow down, requiring high levels of psychological and physical strength to keep moving, to stay alive. Pushed to these limits, the diver hopes to emerge from the water feeling balanced, strong, and, in many contexts, blessed or protected. While Charles Darwin used cold-water immersion to treat his illnesses, the Apache leader Geronimo used it to prepare boys for lives as warriors.5

In Russia, ice plunging is popular on Epiphany, a January holiday commemorating Christ’s baptism in the River Jordan. A hole, often in the shape of a cross, is cut into the ice on a body of water and Orthodox Christians line up to take the plunge. This past Epiphany, Russian President Vladimir Putin participated in the ritual. Robed monks held golden icons in the background as Putin dipped himself in the freezing waters.6 The event was recorded by state-sponsored media in photographs and videos, spreading the message that Putin is a healthy religious man, respectful of tradition, and a participant in the very same ritual performed by many religious Russians. The media event allowed the Russian public to feel a sense of camaraderie with the president while also aligning themselves with Christ, in hopes of achieving eternal life beyond the death of the body.

Putin’s plunge transformed ritual into spectacle. Even if he was experiencing a corporeal or spiritual reset, the resulting images and videos repackaged his experience for media use, giving the event political relevance. Similarly, with A Cold Hole, participants choose how and when they will be seen within the ostensibly neutral, secular space of the museum. They perform the ritual both for personal and for social gain. Fully aware of his or her audience, the participant enters the room, carefully tiptoes across the ice, and stands in front of the hole. In an adjacent room, museum visitors peer in through a rectangular glass window that dramatically frames each isolated body. Simon thus subverts our relationship to the image in two ways. Unlike the rectangular screens of our phones, with which we may capture any image in our surrounding environment, the rectangular aperture looking onto A Cold Hole is set in place; the frame cannot be moved. And, instead of choosing a particular view, the audience must wait patiently for each participant to appear in the room, hesitate before the hole, then disappear with a splash. As the bodies quickly reemerge from the hole, shivering beneath fluorescent lights, the audience erupts into applause.

In this way A Cold Hole is the reverse of Assembled Audience. In the latter, the bodies are invisible, hidden beneath many layers of distortion, manipulation, and recontexualization. The individuals become bits of data, like the many images and news-bites that populate our computer and phone screens at all hours of the day and night. Their claps resemble “likes” on social media: quick approval, involving little deliberation. In the former, on the other hand, Simon gives the body the opportunity to present itself in person. Though framed in a photographlike manner, the participants assert their existence in real, practically unmediated time, requiring patience and empathy from their audience.

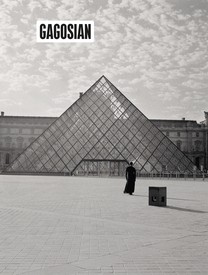

The fact that A Cold Hole takes place in a museum reveals the ways in which ritual and performance are related to posterity. Like the billions of people documenting their daily lives in photographs, the museum as an institution preserves the objects of the past so that they might carry historical information into the future. As such, it is a ritualistic space—a secular echo of the church. Here, paintings and sculptures may live indefinitely, replacing the mortal bodies of the artists who created them.

Seeing posterity as both a religious and a secular concern, the progenitors of Cosmism, a philosophical movement developed in Russia in the nineteenth century, believed that the goal for the future of humanity should be biological immortality, the resurrection of the already dead, and the spread of this immortal population across the infinite cosmos. Cosmism’s founder, Nikolai Fedorov, considered the role that art institutions might play in this pursuit, arguing that the museum should be repurposed as a site for the conservation of humans in the way that it now preserves objects.7 Bodies, like artworks, would be available as vessels of history and information. In Fedorov’s words,

Each man bears a museum within himself, bears it even against his personal wish, as a dead appendage, as a corpse, as reproaches of conscience; for conservation is a basic law, preceding man, having been in force before him. Conservation is a characteristic not only of organic, but of inorganic nature; and especially of human nature. . . . For the museum, death itself is not the end but only the beginning.8

A Cold Hole, by inserting a baptismal ritual into the museum and signaling a rebirth or reset, comes closer to Cosmism’s goal than any discrete art object could. The hole in the ice is cut in a perfect square, linking the work to Simon’s ongoing series Black Square (2006– ), in which she shows objects, documents, and individuals in a black field with the same dimensions as Kazimir Malevich’s 1915 painting of that name. This reference to Malevich, in addition to the sleek, minimalist installation of the exhibition as a whole, uses formal language to intimate a jolt into the new. Yet actual, moving bodies interrupt the abstraction, asking whether it is possible for the body itself to achieve the clean slate proposed by Malevich’s Black Square. Can the body free itself from the data that surrounds it? And, if the body contains its own, unique data, how can this information be conserved, and protected from distortion?

With A Cold Hole | Assembled Audience, Simon makes us absorb information at the pace not of technology or photography but of the mortal body. While in Assembled Audience the bodies are invisible, allowing their sounds to be repurposed, in A Cold Hole they are on full display. Leaping into the dark water, the participants enter a representation of the unknown, as an immortal audience applauds in approval. Throughout the run of the exhibition, Simon will continue to record individual applause tracks and add them to the soundscape. The imagined crowd will thus grow and grow, like enthusiastic ghosts waiting for their bodies to rejoin them in the crowd of the future.

1See Alexandra Foradas, “A Charged Atmosphere of Hope and Uncertainty: Taryn Simon’s A Cold Hole and Assembled Audience,” in the gallery guide for Simon’s exhibition A Cold Hole | Assembled Audience (North Adams, MA: MASS MoCA, 2018), n.p.

2Ibid.

3Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (London and New York: Verso, 1991), p. 7.

4Ibid., p. 35.

5Foradas, “A Charged Atmosphere of Hope and Uncertainty,” n.p.

6See Alex Horton, “Shirtless Putin Takes Icy Religious Plunge, and Yes, There Are Photos,” The Washington Post, January 19, 2018. Available online at www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2018/01/19/shirtless-putin-takes-icy-religious-plunge-and-yes-there-are-photos/?utm_term=.739a1935a466 (accessed June 6, 2018). Epiphany is most often celebrated on January 6; in Russia, however, which follows the Julian calendar, that date falls thirteen days later than in countries following the Gregorian calendar.

7See Molly Nesbit, “Cosmist Rays,” Artforum 56, no. 6 (February 2018), p. 163.

8Nikolai Fedorov, “The Museum, Its Meaning and Mission,” 1906, repr., trans. from the Russian by Stephen P. Van Trees, in e-flux journal 56th Venice Biennale, available online at supercommunity.e-flux.com/texts/the-museum-its-meaning-and-mission/ (accessed June 18, 2018).

Taryn Simon: A Cold Hole | Assembled Audience, MASS MoCA, North Adams, Massachusetts, May 26, 2018–March 24, 2019

Artwork © Taryn Simon