Joshua Chuang is the Miriam & Ira D. Wallach Associate Director for Art, Prints, and Photographs and Robert B. Menschel Senior Curator of Photography at the New York Public Library. Among the exhibitions and publications he has organized are Robert Adams: The Place We Live (2010); Blue Prints: The Pioneering Photographs of Anna Atkins (2018); and Santu Mofokeng: Stories (2019).

Since the industrialization of photography, observers from each generation have remarked on the condition of being awash in images. Relatively few of these images were intended for posterity; most, in fact, were made for a specific reason and time, to be disposed of after fulfilling their purpose. Around 1914, a handful of librarians at the New York Public Library began to salvage some of this pictorial flotsam, recognizing its value as raw material that might be re-consumed, digested, and transmitted by an American public back into the culture from which it came.

The Picture Collection has been called upon by journalists, historians, filmmakers, designers, advertising agencies, and even the US military during its strategic preparations for World War II. But of all the image-seekers to plumb the depths of the New York Public Library’s Picture Collection during its century of continuous operation, Taryn Simon may be the one most obsessed with pictures that are no longer there. Introduced to this quietly legendary trove of images at a young age by her father, an avid photographer, Simon returned to it many years later with the notion that embedded in its files (and the homegrown organizational system that governs its approximately 1.2 million physical images) is a largely untold history of images—one that serves as a prescient counternarrative to that of Google Images and other image-retrieval systems that have not so quietly revolutionized the way we find the pictures we want, and the entire image economy along with it.

The Picture Collection was established just a few years after the main building of the New York Public Library (NYPL), at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue, first opened its doors to a public hungry for information. The staff had found itself ill equipped to satisfy the growing number of patrons who came looking for particular images within the library’s vast holdings. (Among the earliest requests were depictions of ballot boxes, girls playing basketball, and, jarringly, the act of suicide.) They accordingly began to clip and save pictures from worn-out illustrated books and extra copies of newspapers and magazines that would otherwise have been discarded, and then to categorize each image with a subject heading and to sort it with other images on the same theme. The headings were then marshaled into an alphabetical index that could be consulted by the public, who were able to borrow pictures as they would books.

This novel concept did not originate in New York—similar collections had already been established at public libraries in cities such as Denver, Chicago, Boston, Saint Louis, and, most notably, Newark—but the NYPL’s location in the country’s de facto capital of the theater, design, and fashion industries positioned it to be arguably the most influential. Despite having no outlet to promote its services, the collection’s staff was soon besieged by requests for pictures of every conceivable kind; word about its growing holdings, augmented by a continuous stream of donations from its devotees, quickly spread among those whose livelihoods depended on having access to the latest and broadest array of visual references.

In 1929, a twenty-six-year-old Russian émigré named Romana Javitz was promoted to be the collection’s superintendent. More than anyone else, Javitz shaped the ethos and radically democratic practices of the collection during her nearly four-decade tenure, making a point of diversifying its offerings by collecting photographs and other depictions of American folk art and Black life, hardly popular subjects at the time. Having trained as an artist, she is also credited with molding the collection into a stimulating refuge for working artists, many of whom sought her out as a sounding board for their visions and curiosities, recognizing in her boundary-crossing, hierarchy-flattening tendencies an unusually progressive set of values that were on the opposite end of the spectrum from that of, say, the Museum of Modern Art, which was founded the same year as Javitz’s appointment.

Today the Picture Collection stands alone as perhaps the last of its kind: a capacious repository of physical images freely available to the public. The collection’s librarians continue to add to its stock, and patrons can still check out up to sixty images at a time on their library card (although there was a months-long moratorium on borrowing pictures due to the ongoing pandemic). Javitz’s imprint can still be felt in the discoveries latent within its folders, even though the collection is not nearly as voluminous or bustling as it was in her day. (At one point it held over 6 million pictures.)

Simon’s project, scrupulously developed over the past nine years, led her to comb through not only the collection’s circulating folders, whose evolving contents reflect the residual tastes and observations of generations of patrons and librarians, but also its historical archive of papers, through which she assembled an extraordinary narrative of foresight and survival. A meditation on the fate of the images we consume and the forces that compel us to revise what images we value, Simon’s project is also a paean to Javitz’s underrecognized legacy in twentieth-century American art, to which the images following—included in Simon’s recent monograph (Cahiers d’Art, 2020) and forthcoming exhibition The Color of a Flea’s Eye: The Picture Collection (NYPL and Gagosian, New York)—amply testify.

Walker Evans

Aspiring as a young man to become a writer, Walker Evans was a habitué of the NYPL well before he was a serious photographer, at one point working the night shift as a page in the library’s map room. It was at the library that he first saw the issue of Alfred Stieglitz’s journal Camera Work containing Paul Strand’s 1916 photograph of a blind woman, an experience he would later recall as critical in setting his artistic course. Less well documented are the many hours he spent in the Picture Collection, which must have satiated, and perhaps even influenced, his penchant for direct, plain-spoken, and deceptively potent imagery. (It is not a stretch to imagine Evans poring over the collection’s voluminous holdings of picture postcards, which he would later come to collect himself, organizing them by subject in a similar manner.) In the early 1930s, shortly after returning from a trip to Cuba, Evans showed the photographs he had taken there to Javitz, who immediately saw their merit and acquired more than thirty of them to add to the Picture Collection’s files. Later that decade, thousands of photographs commissioned from Evans by the US government’s Farm Security Administration (FSA) were added to the files, courtesy of Roy Stryker, who headed the agency’s photography project and surreptitiously sent Javitz packet upon packet of prints divulging the unvarnished realities of Depression-era American life, out of fear that Congress might suppress them.

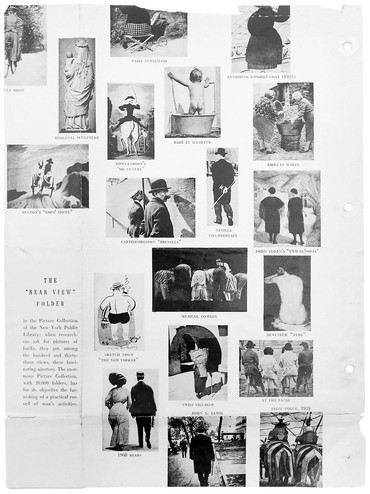

In 1949, Evans was commissioned by Vogue to make pictures to accompany a feature article about the library on the occasion of its centenary. Among the expected pictures ultimately published of the library’s facade, rare volumes, and celebrated main reading room is a full-page layout—surely edited by Evans and included at his insistence—highlighting the subversive delights to be found in the “Rear View” category of the Picture Collection. More than six decades later, Simon was drawn to the same subject heading; a handful of the pictures Evans selected for the Vogue spread (which Simon later discovered in her research) also appear in her triptych.

Joseph Cornell

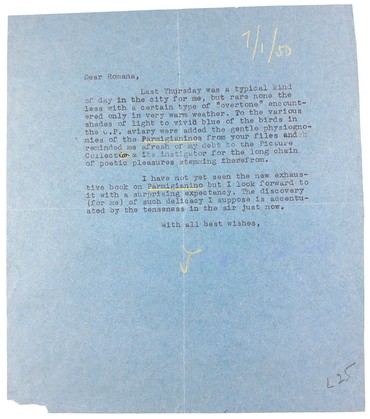

Joseph Cornell’s exquisite shadow box constructions, whose graphic components largely derived from a clippings file he compulsively amassed over five decades, are replete with visual allusions that reveal his voracious cultural appetite. Years before he was compelled to create his own assemblages, the hermetic Cornell was drawn not only to the avant-garde art shown in galleries such as those of Stieglitz and Julien Levy but also to the opera, the ballet, secondhand bookshops, film screenings, and performances by Houdini. Stored in the basement of the modest house Cornell shared with his mother and brother in Queens, his personal reference archive of books, prints, postcards, films, and visual ephemera included a substantial number of photostats made from pictures he selected and borrowed from the Picture Collection, perhaps his favorite image source during the 1940s and ’50s. The reclusive artist had become a familiar presence in the Picture Collection by 1945, the date of his earliest surviving correspondence with Javitz. The two had quickly developed a special connection: in the ecumenical Javitz, Cornell found a kindred spirit who, without batting an eye, would indulge requests as specific as an engraving showing Star Island, Maine, in 1852, the German pianist Clara Schumann as a young woman, or a Victorian street urchin with a white cockatoo. Javitz arranged for Cornell’s experimental films to be screened at the NYPL, and Cornell occasionally left cookies for her, as well as small gifts of his work.

Andy Warhol

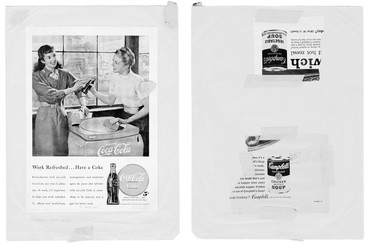

Being the enterprising and prolific commercial illustrator he was in the 1950s, Andy Warhol began to frequent the Picture Collection in search of fresh source material for his slyly irreverent drawings. Later he would find even more reason to spend time in the collection when he commenced an intimate relationship—thought by Warhol biographer Blake Gopnik to be his first—with Carleton Willers, who worked as one of Javitz’s assistants. “Oh, you just go to the Public Library and take out as much as you want,” Warhol once said, “and you just say that you lost them, or they were burned. And you only have to pay two cents a picture.” According to Willers, Warhol was assessed hundreds of dollars in fines, but his borrowing privileges were never revoked. A hand-colored greeting card from the “Cards—Christmas—1954” folder in the Picture Collection offers a clue as to why his recurrent delinquency was tolerated: depicting a ring of children at play, it is inscribed “Happy December rj—Andy Warhol.”

Unsurprisingly, then, the archives of the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, include hundreds of mounted advertisements bearing the stamp of the NYPL Picture Collection. In some cases Warhol taped additional ads torn from magazines on top of them (perhaps the mount provided a convenient stiff support); in others, he gave them new meaning by sealing them in his Time Capsules—personal archive-cum-artworks filled with an eclectic array of source material, correspondence, invoices, and other ephemera from his daily life. While Warhol’s nonconformist borrowing habits deprived his fellow image-seekers access to the pictures he held on to, Javitz must have been privately delighted that the imagery in several of his breakthrough Pop canvases could be traced to what he came across in the collection’s bins. Indeed, she designed the collection to withstand a certain level of attrition; since many of its contents were clipped from popular media, there was little that could not be replaced. From Javitz’s perspective, pictures achieved their highest purpose when they were put to work, pressed into service in the creation of something new.

Dorothea Lange

In May 1957, Javitz received an unexpected letter from an old acquaintance, Dorothea Lange. “My dear Miss Javitz,” Lange wrote, “For some time now I have been gathering together a record which I started in my earliest days as a documentary photographer. These photographs . . . were made with no particular purpose in mind except that I was strongly moved by what was surrounding us during those days. Most of these have never been exhibited, nor shown to anyone. . . . My query to you is, What should I do with this group? I would like to place it where it can be seen and used and serve purposes.” The Picture Collection already had a few thousand of Lange’s photographs for the FSA, an embarrassment of riches that Stryker had deposited there, as he had with Evans, but it had none from her earlier period of work. Javitz seized the opportunity, eventually purchasing fifty-five prints for a total of $275. Delighted with the transaction, Lange continued her correspondence with Javitz over the next few years, leading to the Picture Collection’s additional acquisition of more than 300 prints spanning Lange’s entire output.

Taken together, the NYPL’s collection of over 3,500 of Lange’s photographs constitutes one of the greatest collections of her work outside the Oakland Museum of California, the site of her archive. In the 1980s, as library officials became alert to the cultural significance and rising market value of this collection—along with that of tens of thousands of other photographs enmeshed within the Picture Collection’s files—it started a gradual campaign of removing them from their subject folders and transferring them to a newly formed Photography Collection. Here they could be viewed and cared for as works of art, a change in status critiqued by the critic Douglas Crimp in his oft-cited 1981 essay “The Museum’s Old, the Library’s New Subject.”

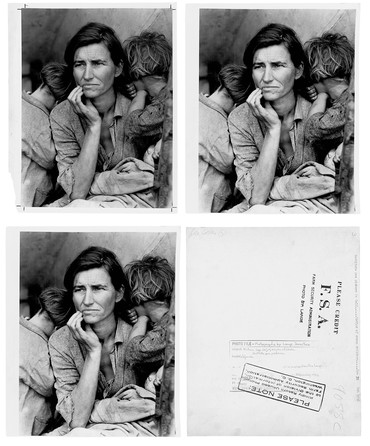

Among these transfers, highlighted in Simon’s new book, were multiple vintage prints of Lange’s Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California (1936), perhaps the best-known documentary photograph of the twentieth century. Each is marked with an official government stamp and inscribed with its full title, and one of them bears evidence of having actually been used for reproduction, the intended function of the prints made by the FSA. No longer circulating, their place in the collection presents a conundrum: their simultaneous potential as universal icon, valuable commodity, and functional document.

Taryn Simon: The Color of a Flea’s Eye: The Picture Collection, Gagosian, 976 Madison Avenue, New York, July 14–September 11, 2021

Taryn Simon: The Color of a Flea’s Eye: The Picture Collection, New York Public Library, Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, September 18, 2021–May 15, 2022

Organized by Simon with Joshua Chuang, The Color of a Flea’s Eye: The Picture Collection is accompanied by a comprehensive monograph of the same title, published by Cahiers d’Art