Angela Brown is a writer and editor from Yonkers, New York. She is currently a PhD student in modern art history at Princeton University.

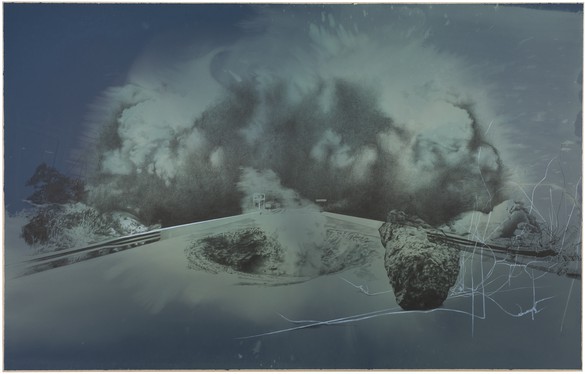

Dust rises out of a deep crater in the center of a highway. Has an asteroid hit? A jagged wound interrupts an otherwise smooth wall of rock, and fissures spread through the concrete. Has there been an earthquake? Charred tree branches and debris pile up on a bed of ash, and a huge cloud of smoke obscures the horizon. Is the forest on fire?

Where are we?

Tatiana Trouvé might reply: You are here.1

Trouvé’s work frequently grapples with the ways in which we manage to orient ourselves in real and imagined spaces. Her drawings are made up of visual fragments from the studio, the street, or her personal archive of found and original images. She projects these disparate object-moments onto the picture plane and captures them there in graphite—resurrecting the intangible spaces of thought and memory alongside references to so-called reality. Trouvé’s sculptures, on the other hand, introduce physical and temporal confusions into existing spaces (galleries, museums, cities, and forests). By casting plastic bags and wilted cardboard in bronze or carving tattered cushions and mattresses out of stone, she gives common, typically disposable objects a resolute endurance. Displayed together, the drawings and sculptures render time material and matter temporal.

We are disoriented.

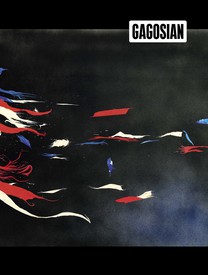

Though inside and outside often overlap in Trouvé’s work, the work in the exhibition On the Eve of Never Leaving at Gagosian in Beverly Hills more explicitly pulls the viewer into the charged arena of the natural landscape. Trouvé offers environmental mise-en-scènes that are familiar yet destabilizing—thus provoking strings of questions like the ones that open this essay. The exhibition comprises works from two related series of drawings—The Great Atlas of Disorientation (2019–) and Les dessouvenus (2013–)—as well as several sculptures, including The Shaman (2018), a bronze-cast tree, partially submerged in a pool of water beneath a ruptured concrete floor. For Les dessouvenus, Trouvé plunges large sheets of colored paper into bleach, then allows the caustic boundaries of each stain to provide a loose structure for a drawing; and in The Great Atlas of Disorientation, she uses watercolor to re-create these bleached effects, then takes the drawings in new directions. Underscoring the impossibility of repeating chance events, the Rorschach-like forms become mushroom clouds and ghostly auras—unpredictable backdrops for environments that exist somewhere between studio, apocalyptic landscape, and dream.

Are we in LA?

Though Trouvé lives and works in Paris, her works function as non-places or portals, which inevitably—and often unintentionally—reflect aspects of the places in which they are displayed. The distinctly ecological bent of the works in On the Eve of Never Leaving becomes especially charged in Los Angeles, a city always recovering from or waiting for the next natural disaster to strike.

Prone to wildfires and drought, to earthquakes and shifting fault lines, the California landscape does not always live up to the mythologies that paint it as a tranquil, sunny paradise.2 Urban theorist and historian Mike Davis argues that in Southern California, disaster is the norm.3 Yet instead of expecting such events, people often treat them as a shock, even a betrayal: “The weather is ceaselessly berated for its perversity. . . . [And] despite daily reminders that ‘we live in earthquake country,’ every high-intensity natural event . . . produces shock and consternation.”4

Though it sounds apocalyptic, an acceptance that nature can and will overpower us—in other words, a decentering of human influence—can have radical implications for the ways in which we learn to adapt to our rapidly changing world.

Because art has long been concerned with humans’ relationship to the landscape, it offers valuable insight into how we react to nature’s power. At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass (2012), a huge boulder suspended over an outdoor walkway, draws attention to the fragility of the body in relation to geological forms. And in his Psycho Spaghetti Western paintings from the early 2000s, Ed Ruscha drops us into what feels like a post-human desert, in which blown tires, torn-up armchairs, cardboard boxes, and even a Perrier bottle drift across the dry, flat land like tumbleweeds. These are not the fertile, welcoming landscapes of the romanticized West, but the hot, harsh reality of the Southern California desert, traversed by roads and highways.

Instead of Heizer’s hovering threat or Ruscha’s humanless expanses, Trouvé’s works seem to suspend the moment immediately following the catastrophic event: after the fire, but before the smoke has cleared. Water still trickles from the uprooted tree; a fuming crater interrupts the perspectival flow of the open road—as if Heizer’s rock has dropped down into Ruscha’s desert highway.

In April (2019), from The Great Atlas of Disorientation, hanging plastic bags and bent metal poles can be seen in the darkness, among fallen and standing trees. On the left, a row of images—including a vintage X-ray of a skull—lead the eye deeper into the night, to other times and places. In another Les dessouvenus work, a remembered image of two hands toying with a white string appears in a room of drawing mannequins. Despite their human resemblance, the mannequins seem to be the least in control of the space; rather, perpendicular black lines and bleach splatters animate the composition, giving it a charged, scientific air. We cannot merely speed toward the future; we must find a way through the dust and fumes.

As multispecies feminist theorist Donna Haraway suggests, we must “stay with the trouble.”5

In her 2016 book Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Haraway proposes an alternative to the concept of the Anthropocene, a term that has gained in use in recent years as a way to describe a world in which human activity is the driving force of global ecosystems and their fates. Haraway traces the term to the early 1980s, when University of Michigan ecologist Eugene Stoermer first used it to “refer to growing evidence for the transformative effects of human activities on the earth,” such as the planet-altering effects of the mid-eighteenth-century steam engine, powered by coal.6 In 2000 atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen proposed that the consequences of human activities were of such a magnitude that they warranted “a new geological term for a new epoch, superceding the Holocene, which dated from the ends of the last ice age, or the end of the Pleistocene, about twelve thousand years ago.”7

Haraway argues that the Anthropocene represents a fatalist, and maybe even a fatal, way of looking at things. Rather, she proposes the Chthulucene, an epoch in which all creatures live in a present that is thick with the past and the future. (Chthulucene is a compound word, devised by Haraway, that combines the Greek χθών [khthôn], which refers to the earth or soil, and καινός [kainos], the root of the suffix –cene, which denotes “newness.”) While in the discourse surrounding the Anthropocene, the future is thought of as a time of either apocalypse (complete environmental ruin) or salvation (the result of some miraculous scientific panacea), in Haraway’s Chthulucene all creatures find new ways to relate deeply to the present, to responsibly adapt to the effects of human-made and natural disasters. “Our task,” Haraway writes, “is to stir up potent response to devastating events, as well as to settle troubled waters and rebuild quiet places.” She continues, “Staying with the trouble requires learning to be truly present . . . as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings.”8

How do we live entwined?

Trouvé’s studio practice can be seen as a real, working manifestation of Haraway’s seemingly abstract proposition. In the studio, everything acts upon everything else in infinite combinations. The movements of Trouvé’s dogs or the sounds of rain against the windows affect the work as much as objects, sculptural materials, and reference images do. When a work begins to cleave away from the series or exhibition it was originally intended for, it remains in the ecosystem of the studio. The “disaster” is not an apocalypse, but an opening onto another, future world.

Trouvé examines the temporal fluctuations of memory itself—allowing past and future possibilities to play out in unresolved realms.

Like Trouvé’s studio, urban and natural landscapes hold records of their histories. Less than ten miles away from Gagosian’s Beverly Hills gallery, the iconic Great Wall of Los Angeles (1976–83) is a tour de force of historical thickness. Painted by Judy Baca with the help of hundreds of local teenagers, the half-mile-long mural depicts major events in California’s history, from prehistoric times to the 1950s, as a continuous narrative.9 The 1930s section of the wall, for example, depicts Dust Bowl refugees arriving from the plains; Mexican immigrants being deported; and a group of Native Americans holding unsigned treaties regarding their rights to the land.10 As art historian Anna Indych-López observes, “Baca uses the formal device of the meandering line in various motifs and guises—as horizon line, as filmstrip, as movie screen, as mountainscape—to unite discrete narratives.”11 Thus, the viewer, who must walk along a flood control channel and peer down into the wash in order to take in the entirety of the mural, is guided through history both physically and visually. By following Baca’s meandering lines, one experiences the interconnectedness of depicted events. The events may be separated by time, but their cumulative effects literally form the present.12

As the Great Wall shows, the catastrophes of the past do not simply stay in the past. Rather, they are active catalysts in the present, and therefore have the potential to motivate change. While Baca expresses this reverberation through geographically specific narratives, Trouvé examines the temporal fluctuations of memory itself—allowing past and future possibilities to play out in unresolved realms that could just as easily be the Los Angeles of tomorrow as the Alps of yesterday.

On the Eve of Never Leaving is further testament to Trouvé’s ability to multiply worlds. Its title comes from a poem by Álvaro de Campos, one of the many heteronyms of the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa. In his emotionally charged verses, de Campos embodied Pessoa’s concept of sensacionismo, one of the main principles of which is the abolition of “the dogma of personality,” using art and sensation to “become everything in every way.”13

The Shaman, in particular, emerges from Trouvé’s interest in how disorientation can allow for new modes of thinking and being. When we are lost or turned upside-down, all givens are destabilized, including the self. Beside the muddied tangle of roots, a limp stack of cushions, carved in marble and granite, are draped over a bronze cast sawhorse, which sits in the pooling water, raising questions about the causes and consequences of this tectonic disruption. For Trouvé, the shaman is an expert in disorientation, seamlessly traveling through space and time, shifting between species and languages, and—like Pessoa—becoming everything.

Like the Great Wall, a tree contains a record of its history. Its surface and interior bear the marks of its growth. Thus, when torn from the earth, The Shaman does not simply cease to exist. Instead, it rearranges its past, present, and future—roots in the air, branches on the ground. It finds new ways to relate to water, rock, and concrete, as its future gently pools around it. The Shaman is a creature of the Chthulucene. It lives entwined.

1You Are Here is the title of a site-specific work that Trouvé made as part of a collaborative project with sound artist Grace Hall for the exhibition Elevation 1049: Avalanche in Gstaad, Switzerland, in 2017. The Elevation 1049 website explains: “A printed map guides visitors to some lesser-known aspects of the region and on an uncanny and disorientating experience for the senses. [The work] takes the form of a guide with five texts relating to five different places. Here, the secret aspects of the region are presented as stations in the exploration of the unknown.” “Tatiana Trouvé: You Are Here, 2017,” January 17, 2017. Available online at https://www.elevation1049.org/2017/tatiana-trouve-grace-hall/you-are-here.html (accessed September 4, 2019).

2Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1998), p. 12.

3Davis, Ecology of Fear, p. 25.

4Davis, Ecology of Fear, p. 16.

5Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), p. 1.

6Haraway, Staying with the Trouble, p. 44.

7Haraway, Staying with the Trouble, p. 44.

8Haraway, Staying with the Trouble, p. 1.

9Maximilíano Durón, “Concrete History: Chicana Muralist Judith F. Baca Goes from the Great Wall to the Museum Wall,” Artnews.com, April 19, 2017. Available online at http://www.artnews.com/2017/04/19/concrete-history-chicana-muralist-judith-f-baca-goes-from-the-great-wall-to-the-museum-wall/ (accessed August 17, 2019).

10See Guisela Latorre, “Chapter 5: Gender, Indigenism, and Chicana Muralists,” in Walls of Empowerment: Chicana/o Indigenist Murals of California (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008).

11Anna Indych-López, Judith F. Baca, A Ver: Revisioning Art History, volume 1 (Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2018), p. 139.

12Indych-López, Judith F. Baca, p. 139.

13Filipa de Freitas, “Naval Ode Translations: Reading the Poet’s Dispositions,” Pessoa Plural, no. 8 (Fall 2015) (Special Jennings Issue), p. 131.

Tatiana Trouvé: On the Eve of Never Leaving, Gagosian, Beverly Hills, November 1, 2019–January 11, 2020