Artist to Artist: Spencer Sweeney and Peter Doig

Peter Doig visits Spencer Sweeney’s studio and the two discuss automatism, ambiguity, and anguish in the creative process.

Fall 2024 Issue

Old friends chat about their love of music, nightclub paintings, life lessons from aikido, and Sweeney’s upcoming exhibition The Painted Bride, at Gagosian, New York.

Spencer Sweeney in his studio, New York, 2024

Spencer Sweeney in his studio, New York, 2024

LIZZI BOUGATSOSSo, Spencer, you’ve been a dear friend and confidant to me since 1997. We’ve collaborated on curating exhibitions like The Living Theater [2015], on playing music with my band I.U.D., and on acting projects. Endless collaborations, from recording music to countless studio visits.

SPENCER SWEENEYTitling drawings and paintings.

LBTrue. I’m also honored that you’ve made drawings and paintings of me. I remember the first time I met you, you had a pencil mustache like John Waters and you were wearing your famous—

SSI was wearing the tight pants, was it?

LBWell, can I say it? You were wearing very tight pants that were duct taped.

SSAt the sides, yeah. That was some kind of DIY sartorial trip I was on. They weren’t making tight pants for men in the ’90s so I used to make my own with boys’ or women’s pants and duct tape.

LBI feel like a lot of guys did this, but I participated too [laughter]. I want to get to the heat of this interview, which is your upcoming, much-anticipated exhibition [The Painted Bride,] in September at Gagosian. In your exhibition at the Brant Foundation, the reclining nudes in that big room were reminiscent of [Henri] Matisse; I know you also love Bob Thompson, David Hockney, Joe Coleman. We both love [Francis] Picabia and I see Picabia in a lot of your portraits. But I’m wondering what your thoughts are on some other artists, like Philip Guston and Peter Saul?

SSGuston is definitely an influence. I’ve had a real attraction to his work since I was young. I always connected with his way of depicting forms, and later on I began to understand him as a colorist and a master of composition. I love Peter Saul as well.

LBDo you? That makes sense.

SSYeah. I was really interested in the work he was doing in the ’60s, and at one point when I was in high school, I took a trip to New York City and I saw an ad for a Peter Saul exhibit; it was at a gallery uptown and I went. It was maybe my second trip to New York City. I don’t remember the name, but it was one of those smaller Upper East Side galleries. I rang the bell and they let me in. I told the gallerist I really loved Saul’s work and he took me into the back room, opened up the flat files, and took out all of these works on paper—they were so beautiful—and just spent hours with me looking through them.

LBThat’s cool. You sent me pictures of some of your black-charcoal drawings on linen. They’re sort of classical Greco-Roman. For me, they’re also a little [Martin] Kippenberger-esque. They’re just quite elegant. The simplicity. . . . I was wondering, are you planning to leave them like this? What’s the plan?

SSAs opposed to painting them over, making them into paintings?

LBYeah, like adding color.

Spencer Sweeney and Lizzi Bougatsos in Sweeney’s studio, New York, 2024

SSI don’t want to add any color to them. This combination of just the charcoal on the linen, I’m finding that to be very easy on the eyes. I like the combination of those two tones and I like the materiality of it too, because the linen isn’t primed or treated with anything. It’s raw and I like the way it absorbs the light, creating no reflection.

LBHow did this series come to be?

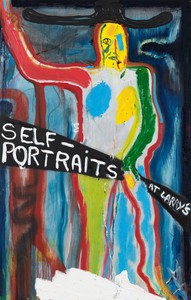

SSWell, these particular drawings are nude self-portraits, and the poses are very stilted artist’s-model-type poses. So that appealed to me, to take on these specific poses that you might see in a life-drawing class and then work my own self-portraits into those.

LBOr sex poster or calendar art. Some of the poses remind me of a Playboy calendar.

SSYes. They’re a bit beefcakey, aren’t they? The poses have this kind of stilted sensuality, which appeals to me.

LBAnd the Kippenberger part for me is the humor in the portrayal of the portraits.

SSThere’s a certain level of humor through self-deprecation that Kippenberger would often use in his depictions of himself. That we have in common.

LBAnother element I always wonder about is your devoted aikido practice and teaching. How does that affect your line, your gesture, your form?

SSAikido is one of these arts that ends up being infinitely applicable to other parts of life, to your work, to your relationships, to your day-to-day. Aikido is all about movement; painting is of course also movement based, in that you move in a certain way to create a certain quality of line or mark. Sometimes it has to be fast and large, other times slow and small, whatever the moment calls for. But at the end of the day, the quality and expression of the marks have everything to do with the movement of the hand, the body, and the eye, and in that there’s an obvious relation to aikido. I’ve been told at the dojo that I make very large movements when I do aikido; I’ve been told the same thing about my painting. One similarity I’ve recognized between aikido, painting, and performing or composing music is this: in aikido the first thing you do is get out of the way of the attack so you don’t get hit; then the force, direction, and nature of that attack reveal the appropriate technique to use. I find it’s similar with painting—you want to get out of the way of the painting and of the creative process. If you’re sitting down at an organ to play Bach, you want to disappear and get out of the way of the music. So it becomes very much about losing yourself and being in the moment, which is also a big part of improvisation.

LBWhen you make a bold stroke, do you imbue it with a sense of importance? Versus a gestural, whimsical, [Vasily] Kandinsky-like painting stroke—those tend to be a little bit more on the outside of your paintings. And specifically I’m wondering how you approach color when you make these strokes? Is it intuitive? Is it planned?

SSSometimes you’ll just have these visualizations for color-scheme ideas. Somehow it’s been transmitted to you, this idea of how to create a mood, and it might say, “Make this painting with a pale pink traveling into a gray with a chartreuse figure surrounded by it.” And you don’t know where this comes from but you get to work. Often in the morning the idea will come to me in a half-dream state. Sometimes it’s an idea for a painting that will come to me in an image. Sometimes it’s a song, it’s like you hear the lyrics sung to you melodically. Then you have to grab your notebook or record it. And that becomes what allows you to live your life and make what you do.

LBI have the same experience. The notebook is always there.

SSDo you ever wake up singing a song and you have no idea where it came from? Not an existing song, but like this lyrical idea that’s been put into your head?

LBFor sure.

SSIt’s such a wild phenomenon.

LBA lot of my sculptural ideas come from being half-awake, and if you don’t write them down—

SS—they just evaporate. I think that’s part of the practice: prioritizing recording these moments. You need little tricks, you need notepads or recorders. And you need to be diligent about catching them and containing them.

Then to answer the part of your question about the significance of the line: a mastery of line can articulate things completely in terms of volume and substance without any need for shading or any other technique. And then when it comes to making the bold stroke feeling, when you lean into that bold stroke and you get it just right, it can completely embody the intent and emotional direction of the work, so that can be a really satisfying move. Sometimes I think about it in terms of Beethoven, and Beethoven’s endings in particular. He’s a master of ending a piece of music, like dun dun . . . dun dun [counts] two . . . three . . . dun dun!

LBSo do you know when a painting’s done?

SSSometimes you hit those Beethoven endings.

Spencer Sweeney in his studio, New York, 2024

Improvisation is one of the most important things to learn how to use in life. . . . If you start to anticipate something, it’s over. It’s the same between control and the loss of control.

Spencer Sweeney

LBI love this. Let’s talk more about sound. How many sets of speakers do you have and can you explain your fascination with them?

SSI think I have about four or five, no, six or seven, maybe seven sets of speakers. I grew up in a musical family and I therefore have a musical mind, so I’m always thinking in musical terms, even in relation to painting and mark making. I’m always playing music, recorded music or an instrument. I don’t see much of a separation between creating visual art and creating music. I think it all calls on the same sensitivities—you know, painting, music, cooking, one or two other things [laughs].

LBLooking at this painting [on the wall in the studio], are these grids a nightclub reference? They remind me of Denzil Forrester, who painted nightclub paintings in the ’80s, right?

SSYeah! He’s done some of the best nightclub paintings ever, in my opinion. I think three of the great nightclub painters are Toulouse-Lautrec, Denzil Forrester, and Jörg Immendorff.

LBI don’t know the third one.

SSHe was a German cat who painted a lot of nightclub-type scenarios. He was considered a neo-expressionist. Some of his paintings took place in specific nightclubs, like Exile in Cologne. Often the great painters of nightlife are dealing with rendering different just right, it can completely embody the intent and forms of artificial light, and how it hits the bodies of the people in the clubs. Toulouse-Lautrec was dealing with the gas lamps of the Moulin Rouge and places like that. Denzil was doing paintings in reggae and dancehall clubs; he’d decorate and pattern his figures with a light thrown from colored nightclub lights, which end up in spots, stripes, and different shapes on the clothing of the partygoers. It’s a wild and energetic way of capturing the scenario and depicting the figures. Then Immendorff was also dealing with how to illustrate the interaction of figures in low-light nightclub situations. He’d paint these brilliant auras depicting the silhouettes of the figures being hit by colored lights and popping forth from the dark backgrounds. They were really interesting and exciting to me. Come to think of it, nightclub painting is a favorite genre of mine. You were asking me about the grid motif—I don’t know if I directly relate the grid to nightclubs per se. I think of it as a representation of the organization of matter.

LBLike bodies in space. Do you feel like you engage with the low lighting of the nightclub genre?

SSThose artists I mentioned articulate light, they work it into their compositions and color schemes to create these sumptuous pictures. I haven’t worked specifically with depicting light in that way, but my figurative work often relates to dance and various expressions that come about from different poses of the body. The most important part of the nightclub is the humans inside it and what they do with their bodies.

The bold stroke is all about owning it.

Lizzi Bougatsos

LBI know you love Bob Fosse, and your figures are often gestural, with legs upside-down, for example, like performers. What’s your relationship to jazz? Is jazz aikido? Is it improvisation?

SSI think there are many parallels. Aikido and playing music can be essentially improvisational. In both you really have to trust in the technique. Improvisation is one of the most important things to learn how to use in life, and in human relationships—when you can engage every situation with zero expectation, you reveal your actual true self. If you start to anticipate something, it’s over. It’s the same with painting. It’s a balance between control and the loss of control, one being just as important as the other. You learn how to control things to set yourself up for a fruitful experience with the loss of control, which is often where the magic happens. Our band Actress was pretty much purely improvisational. I think the first couple of performances were just “Go into a room and do something.”

LBPlay chess.

SSYeah, somebody’s got to do something different. That was the move on the chessboard for that time and place. That was my understanding of the group’s function and purpose. There was almost a sense of urgency to it. It was kinda like, somebody’s got to do something weird right now! And it seemed clear we were the right people to do it. I remember the artist Steven Parrino was at one of our first performances.

LBThe one at [MoMA] PS1[, New York]?

SSI think so. He came up to me after the performance and said, “I really liked that and I’d like to invite you over to my studio.” This was probably 1997 or ’98 or around then. So of course I went to visit him in his studio. Everything was painted silver—the floors, walls, everything. It was his garage. His motorcycles and his paintings were there. It was such an amazing environment. Anyway, he said, “You know, I really appreciate what you guys were doing because you’re starting from nothing. You’re just pulling it up from the void. There’s no plan.” And that was exactly how I was thinking about it as well. He read it right away. And he said, “So that’s totally scary and I really appreciate what you guys are doing” [laughter]. You make an announcement that you’re going to do it and then you go in with zero plan, so it was just total improvisation.

LBImprovisation is a huge part of my practice as well. I remember Kim Gordon said to me, “You have this stage and when you step on it, you have to own it. Because if you don’t, you completely fail.” And the anxiety of that—of being a failure, of not owning that space—is a risk you take. I think you and I both share this approach to the world. You never know what moods you’re going to feel when you listen to the same song twice. You can’t own the void.

SSThat’s what Kim’s saying: nobody owns the void, but there you are and you have to own it anyway.

LBWhich brings us back to the bold stroke. Because the bold stroke is all about owning it.

SSThe bold stroke also has very much to do with what you’ve learned and what you’ve cultivated. That’s something you’ll never lose, even in the moments of pure improvisation.

Artwork © Spencer Sweeney; photos: Peter Sieper

Spencer Sweeney: The Painted Bride, Gagosian, 541 West 24th Street, New York, September 13–October 19, 2024

Lizzi Bougatsos is an experimental musician and visual artist. Her most recent solo exhibition, Idolize the Burn, an Ode to Performance, at tramps, New York, was featured in the New York Times, the Marfa Journal, Artforum, Frieze, Vogue, Purple Magazine, and other publications. Her notorious band Gang Gang Dance has performed worldwide for two decades, at venues including the Sydney Opera House, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the 2008 Whitney Biennial. Lizzi is one-half of the hypnotic duo I.U.D. She lives and works in New York and is represented by James Fuentes and Galerie Molitor. Photo: K.O. Nnamdie

Spencer Sweeney is known for his psychologically rich paintings, as well as for two decades of collaborations with musicians, performers, and artists in the downtown New York art scene. His creative work oscillates between performance, music, visual art, and experimental theater, most recently in his studio salon headz, a communal art and improvisational jazz performance space. Sweeney’s paintings often show reclining nudes, portraits, and self-portraits, spanning various degrees of figuration and abstraction. Photo: Rob McKeever

Peter Doig visits Spencer Sweeney’s studio and the two discuss automatism, ambiguity, and anguish in the creative process.

Spencer Sweeney shares a selection of songs that have punctuated his journey through the pandemic and ponders the expressive powers of a playlist.

Curator and concert promoter Edek Bartz speaks with the artist about portraiture, album covers, and subverting expectations.

Kembra Pfahler speaks with Sweeney about his work, staying inspired, and the relationship between self-portraiture and performance.

Grace Coddington, fashion editor and former creative-director-at-large for American Vogue, meets with the Quarterly’s Derek C. Blasberg to reminisce on some of her most iconic collaborations with photographers and artists.

Architect and designer Jayden Ali joins Gagosian associate director Péjú Oshin for a conversation about false notions of failure, four-day workweeks, and the connective power of building together.

The Warp of Time celebrates a hundred years of shared history between the Old Carpet Factory, a historical mansion located on the Greek island of Hydra, and Soutzoglou Carpets. Here, Salomé Gómez-Upegui interviews curator Ekaterina Juskowski about Helen Marden’s woven works within the context of the exhibition, touching upon themes of history, memory, and creative expression.

John Elderfield and Lauren Mahony of Gagosian speak with the National Gallery of Art’s Harry Cooper about the new and expanded version of Elderfield’s 1989 monograph on Helen Frankenthaler that Gagosian, in collaboration with the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, will publish this summer. The conversation traces Elderfield’s long interest in Frankenthaler’s work—from his time as a young curator at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, to the present—and reveals some of the new perspectives and discoveries awaiting readers.

Sébastien Delot is director of conservation and collections at the Musée national Picasso–Paris and the organizer of the first retrospective to focus on Anselm Kiefer’s use of photography, which was held at Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain et d’art brut (Musée LaM) in Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France. He recently sat down with Gagosian director of photography Joshua Chuang to discuss the exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Punctum at Gagosian, New York. Their conversation touched on Kiefer’s exploration of photography’s materials, processes, and expressive potentials, and on the alchemy of his art.

On the occasion of Art Basel 2024, creative agency Villa Nomad joins forces with Ghetto Gastro, the Bronx-born culinary collective by Jon Gray, Pierre Serrao, and Lester Walker, to stage the interdisciplinary pop-up BRONX BODEGA Basel. The initiative brings together food, art, design, and a series of live events at the Novartis Campus, Basel, during the course of the fair. Here, Jon Gray from Ghetto Gastro and Sarah Quan from Villa Nomad tell the Quarterly’s Wyatt Allgeier about the project.

The Olympic and Paralympic Games arrive in Paris on July 26. Ahead of this momentous occasion, Yasmin Meichtry, associate director at the Olympic Foundation for Culture and Heritage, Lausanne, Switzerland, meets with Gagosian senior director Serena Cattaneo Adorno to discuss the Olympic Games’ long engagement with artists and culture, including the Olympic Museum, commissions, and the collaborative two-part exhibition, The Art of the Olympics, being staged this summer at Gagosian, Paris.

In 2023, the collector and patron of the arts Gemma De Angelis Testa donated over 100 artworks from her collection to the Ca’ Pesaro Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna in Venice. On the heels of that exhibition, she met with Gagosian senior director Pepi Marchetti Franchi to discuss the genesis of her collection, the key role of her organization ACACIA (Friends of Italian contemporary art association) in enriching the world of contemporary Italian art, and what it means to share one’s collection with the public.